MARCH 2023

NATIONAL LOW INCOME HOUSING COALITION

A SHORTAGE OF AFFORDABLE HOMES

MARCH 2023

ANDREW AURAND

Senior Vice President for Research

DAN EMMANUEL

Senior Research Analyst

EMMA FOLEY

Research Analyst

MATT CLARKE

Writer/Editor

IKRA RAFI

Creative Services Manager

DIANE YENTEL

President and CEO

ABOUT NLIHC

The National Low Income Housing Coalition is

dedicated to achieving racially and socially equitable

public policy that ensures people with the lowest

incomes have quality homes that are accessible and

affordable in communities of their choice.

Founded in 1974 by Cushing N. Dolbeare, NLIHC

educates, organizes, and advocates to ensure decent,

affordable housing for everyone.

Our goals are to preserve existing federally assisted

homes and housing resources, expand the supply of low

income housing, and establish housing stability as the

primary purpose of federal low-income housing policy.

MARCH 2023

A Shortage of

Affordable Homes

TABLE OF CONTENTS

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1

INTRODUCTION 3

A SEVERE SHORTAGE OF AFFORDABLE AND AVAILABLE HOMES 4

Affordable Rental Homes 4

Affordable, But Not Available 6

Recent Declines in Affordable and Available Rental Homes 9

HOUSING COST BURDENS 10

WHO ARE EXTREMELY LOW-INCOME RENTERS? 12

RACIAL DISPARITIES AMONG EXTREMELY LOW-INCOME RENTERS 13

HOUSING SHORTAGES FOR EXTREMELY LOW-INCOME RENTERS BY GEOGRAPHY 15

Shortages by State 15

Shortages in the 50 Largest Metropolitan Areas 18

LOCAL SOLUTIONS TO AFFORDABLE HOUSING DEVELOPMENT 20

FEDERAL POLICY SOLUTIONS TO REDUCE THE SHORTAGE OF AFFORDABLE HOMES 22

CONCLUSION 24

ABOUT THE DATA 25

FOR MORE INFORMATION 25

REFERENCES 25

APPENDIX A: STATE COMPARISONS 29

APPENDIX B: METROPOLITAN COMPARISONS 30

T

he nation’s lowest-income renters have long

faced a severe shortage of aordable housing,

and the problem has only worsened in recent

years, as record-high ination and the loss of low-

cost rental homes have impacted renters nationwide.

ough ination has cooled and rent prices have

attened entering 2023, the nation’s lowest-income

renters still face enormous challenges nding and

maintaining safe and aordable rental housing.

Each year, the National Low Income Housing

Coalition (NLIHC) estimates the availability of

aordable rental homes, with a particular focus on

the housing needs of households with extremely

low incomes, dened as incomes at or below either

the federal poverty guideline or 30% of the area

median income (AMI) – whichever is greater. ese

households account for one-quarter, or 11 million,

of the nation’s 44.1 million renters and experience

signicant rates of nancial and housing precarity.

NLIHC’s annual Gap report provides estimates of

aordable housing needs in the U.S., including in

each state, the District of Columbia (D.C.), and the

largest metropolitan areas. e key ndings of this

year’s report are as follows:

1 “Renters” and “renter households” are used interchangeably throughout this report to refer to renter households.

• e shortage of aordable rental housing

primarily impacts renters with extremely low

incomes. Extremely low-income renters in the

U.S. face a shortage of 7.3 million aordable

and available rental homes, resulting in only 33

aordable and available homes for every 100

extremely low-income renter households.

1

• e shortage of aordable rental housing

worsened during the pandemic. Between

2019 and 2021, the shortage of aordable and

available rental homes for extremely low-income

renters worsened by more than 500,000 units, or

8%.

• Black, Latino, and Indigenous households

are disproportionately extremely low-income

renters and are disproportionately impacted by

this shortage. Nineteen percent of Black non-

Latino households, 17% of American Indian or

Alaska Native households, and 14% of Latino

households are extremely low-income renters,

compared to only 6% of white non-Latino

households.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

1

NATIONAL LOW INCOME HOUSING COALITION

THE GAP A SHORTAGE OF AFFORDABLE HOMES, 2023

• Extremely low-income renters are the most

likely renters to spend a high share of their

income on rent. Seventy-two percent (8.1

million) of the nation’s 11.0 million extremely

low-income renter households are severely

housing cost-burdened, spending more than

half of their incomes on rent and utilities. ey

experience severe cost burdens at more than

double the rate of any other income group

and account for more than 72% of all severely

housing cost-burdened renters in the U.S.

• e dearth of aordable and available homes for

extremely low-income renters impacts all states

and the 50 largest metro areas, none of which

have an adequate supply for the lowest-income

renters. e current relative supply by state

ranges from 17 aordable and available homes

for every 100 extremely low-income renter

households in Nevada to 58 in South Dakota. In

12 out of 50 of the country’s largest metro areas,

the absolute shortage of aordable and available

homes for extremely low-income renters exceeds

100,000 units.

ese ndings underline the importance of large-

scale, long-term policy solutions to meet the

housing needs of renters with the lowest incomes.

Any reduction in federal aordable housing

resources will only exacerbate the existing shortage,

which is already acute. e federal government

must preserve and expand the stock of deeply

aordable housing, expand housing vouchers to all

eligible households, invest in a housing stabilization

program that provides renters with emergency funds

when they experience unexpected nancial shocks,

and strengthen and enforce renter protections. State

and local governments also have an important role

to play in improving access to aordable housing,

including reforming zoning and reducing other

land-use restrictions to bolster aordable housing

development. ese local reforms are necessary, but

insucient without federal resources, for eliminating

the shortage of aordable rental housing for the

nation’s lowest-income renters.

THE GAP A SHORTAGE OF AFFORDABLE HOMES, 2023

NATIONAL LOW INCOME HOUSING COALITION

2

T

he past three years – characterized by a

global pandemic, widespread job losses,

record-breaking ination, unusually low

vacancy rates, and skyrocketing rental prices – have

underlined and exacerbated the nancial precarity

experienced by the nation’s lowest-income renters.

Between January 2021 and December 2022, rental

prices increased 22% nationally (Apartment List,

2022). ese rent increases occurred across the

country and were not conned to certain markets.

As prices increased precipitously, the supply of rental

housing aordable to extremely low- and very low-

income renters declined by more than one million

units, continuing a long-term trend of a diminishing

supply (U.S. Census Bureau, 2022b & 2020; Joint

Center for Housing Studies, 2022; Hermann, 2020).

Meanwhile, rental vacancy rates reached their

lowest point in nearly four decades. With only 5.6%

of rental units vacant at the end of 2021, renters’

choices about where to live became more and more

limited (U.S. Census Bureau, 2023). Despite small

improvements, the average vacancy rate in 2022 was

5.8%, a level not seen since the 1980s (U.S. Census

Bureau, 2023).

ese trends are reected in NLIHC’s most recent

analysis of aordable and available rental homes

for various income groups. Each year, NLIHC

uses American Community Survey (ACS) data

to estimate how many aordable rental homes are

available to extremely low-income households –

those with incomes at or below the federal poverty

guideline or 30% of AMI, whichever is greater – and

other income groups (Box 1). Aordable homes

are those with rents that do not exceed 30% of a

given income threshold. Homes are aordable and

available for a specic income group if they are

aordable and are either vacant or not occupied by a

higher-income household. e Gap report provides

2 Similar analyses, based on a dierent dataset, are available for every county, city, and town in the U.S. and can be acquired by contacting [email protected].

estimates of aordable housing needs in the U.S.,

including in each state, the District of Columbia

(D.C.), and the 50 largest metropolitan areas.

2

Extremely low-income renters likely have even

fewer housing options now than they did prior to

the pandemic. Between 2019 and 2021, the shortage

of aordable and available rental homes for them

increased by 8%, from 6.8 million to 7.3 million

(U.S. Census Bureau, 2022c; U.S. Census Bureau,

2020). As this report shows, we cannot successfully

resolve our aordable housing crisis without housing

assistance that adequately meets the housing needs

of renters with the lowest incomes.

INTRODUCTION

BOX 1: DEFINITIONS

AREA MEDIAN INCOME (AMI): The median family income

in the metropolitan or nonmetropolitan area

EXTREMELY LOW-INCOME (ELI): Households with

incomes at or below the federal poverty guideline or 30%

of AMI, whichever is higher

VERY LOW-INCOME (VLI): Households with incomes

between ELI and 50% of AMI

LOW-INCOME (LI): Households with incomes between

51% and 80% of AMI

MIDDLE-INCOME (MI): Households with incomes between

81% and 100% of AMI

ABOVE MEDIAN INCOME: Households with incomes

above 100% of AMI

COST BURDEN: Spending more than 30% of household

income on housing costs

SEVERE COST BURDEN: Spending more than 50% of

household income on housing costs

AFFORDABLE: Housing units with rent and utilities that do

not exceed 30% of a given income threshold

AFFORDABLE AND AVAILABLE: Rental units that are both

affordable and either vacant or not occupied by higher-

income households

3

NATIONAL LOW INCOME HOUSING COALITION

THE GAP A SHORTAGE OF AFFORDABLE HOMES, 2023

A SEVERE SHORTAGE OF

AFFORDABLE AND AVAILABLE

HOMES

Extremely low-income renters face the most severe

shortage of housing, with only 7.0 million aordable

rental homes for 11.0 million households. Of those

7.0 million rental units, 3.3 million are occupied by

higher-income households, leaving only 3.7 million

rental homes that are both aordable and available

for extremely low-income renters. is section

illustrates how the national shortage of aordable

housing is almost entirely attributable to the

shortage for extremely low-income renters.

Affordable Rental Homes

Extremely Low-Income Renters: Extremely

low-income households account for one-quarter,

or 11 million, of the nation’s 44.1 million renter

households. Using the standard denition of

aordability, which assumes households should

spend no more than 30% of their income on housing,

we nd that only 7.0 million units are aordable to

extremely low-income renters nationally.

3

is supply

leaves an absolute shortage of 4.0 million aordable

rental homes. Extremely low-income renters are the

only income group to face this absolute shortage of

aordable homes; for all other income groups, there

are enough aordable rental units to accommodate

all households (Figure 1).

3 e 30% standard is commonly used to estimate the scope of housing aordability problems and serves as the basis for some administrative policies, but some

households may struggle even at this level of housing cost (Stone, 2006).

Very Low-Income Renters: Approximately 6.8

million renter households have very low incomes

(i.e., incomes between extremely low-income and

50% of AMI), but households in that income group

can aord the same 7.0 million rental homes that are

aordable to extremely low-income renters, as well

as another 9.2 million more expensive rental homes.

In total, 16.2 million rental homes are aordable to

the 6.8 million very low-income renter households.

A cumulative shortage remains, however, when

we examine extremely low- and very low-income

renter households together, for which there are 16.2

million units for 17.8 million households.

Low-Income Renters: Nearly 9.2 million renter

households have low incomes (i.e., incomes between

51% and 80% of AMI). ese renters can aord the

16.2 million homes aordable to extremely low-

income and very low-income renters, as well as an

additional 18.6 million more expensive rental homes.

In total, 34.8 million rental homes are aordable to

the 9.2 million low-income renters.

Middle Income: Approximately 4.6 million renters

are middle-income (i.e., with incomes between

81% and 100% of AMI). Middle-income renters

can aord all the homes that low-income renters

can aord, plus an additional 6.2 million more

expensive rental homes, so the total national supply

of aordable rental housing for that group is 41.0

million units.

EXTREMELY LOW-INCOME RENTERS LIKELY HAVE

EVEN FEWER HOUSING OPTIONS NOW THAN

THEY DID PRIOR TO THE PANDEMIC.

THE GAP A SHORTAGE OF AFFORDABLE HOMES, 2023

NATIONAL LOW INCOME HOUSING COALITION

4

FIGURE 1: RENTAL UNITS AND RENTERS IN THE US, MATCHED BY

AFFORDABILITY AND INCOME CATEGORIES (IN MILLIONS)

Source: NLIHC tabulations of 2021 ACS PUMS data.

Extremely Low-Income Very Low-Income Low-Income Middle-Income Above Median Income

Households

(By Income Category)

11.0m Households

6.8m Households

9.2m Households

4.6m Households

12.5m Households

CAN AFFORD

CAN AFFORD

CAN AFFORD

CAN AFFORD

CAN AFFORD

Cumulative Units

(By Affordability Category)

46m Units

(41.0 + 5.0)

41.0m Units

(34.8 + 6.2)

34.8m Units

(16.2 + 18.6)

16.2m Units

(7.0 + 9.2)

7.0m Units

FIGURE 2: MOST EXTREMELY LOW-INCOME RENTERS RESIDE IN

UNAFFORDABLE HOUSING THAT WOULD OTHERWISE BE AFFORDABLE

AND AVAILABLE FOR HIGHER-INCOME HOUSEHOLDS

NUMBER OF EXTREMELY LOW-INCOME HOUSEHOLDS BY RENTAL AFFORDABILITY LEVEL (IN MILLIONS)

Source: 2021 ACS PUMS

AMI = Area Median Income

3.3 2.6 3.5 0.8 0.5

Affordable at or below

poverty guideline or

30% of AMI (ELI)

Affordable to ELI

to 50% of AMI

Affordable to 51%

to 80% of AMI

Affordable to

81% to 100%

of AMI

Affordable to over

100% of AMI

5

NATIONAL LOW INCOME HOUSING COALITION

THE GAP A SHORTAGE OF AFFORDABLE HOMES, 2023

Figure 1 illustrates the mismatch between the

number of households within an income bracket and

the number of aordable rental homes.

Affordable, But Not Available

e shortage of aordable housing for the lowest-

income renters becomes even more severe when we

take into account the availability of these aordable

homes. In the private market, households can occupy

homes that cost less than 30% of their incomes, and

many do. When higher-income households occupy

rental homes that are aordable to lower-income

households, they render those homes unavailable

to the lower-income households. Extremely low-

income renters must compete with all higher-

income households for the limited number of rental

homes aordable to them in the private market.

Of the 7.0 million homes aordable to extremely

low-income households, only 3.7 million are

available to them either because they are vacant or

because they are already occupied by extremely low-

income renters. Of the 3.3 million aordable units

that are not available, approximately 2.0 million

are occupied by very low-income and low-income

households, and 1.3 million are occupied by middle-

income and higher-income households. at leaves

a shortage of 7.3 million aordable and available

homes for renters with extremely low incomes.

As a result of this shortage, the majority of

extremely low-income renters are forced to rent

homes they cannot aord and that would otherwise

be available to higher-income renters who could

aord them. Among extremely low-income renters,

roughly 2.6 million reside in homes aordable to

very low-income households, 3.5 million are in

homes aordable to low-income households, and 1.3

million reside in homes aordable to middle-income

and higher-income households (Figure 2).

e relative supply of aordable and available rental

homes improves as incomes increase, because more

housing becomes available to renters at higher

incomes. For every 100 extremely low-income

renter households, there are only 33 aordable and

available rental homes (Figure 3). Fifty-ve rental

homes are aordable and available for every 100

renter households with incomes at or below 50%

of AMI. Ninety and 99 rental homes are aordable

and available for every 100 renter households

with incomes at or below 80% and 100% of AMI,

respectively. e shortages are cumulative, so the

FIGURE 3: THE RELATIVE SUPPLY OF AFFORDABLE AND AVAILABLE RENTAL

HOMES INCREASES WITH INCOME

AFFORDABLE AND AVAILABLE RENTER HOMES PER 100 RENTER HOUSEHOLDS, 2021

Source: 2021 ACS PUMS

AMI = Area Median Income

At 100% AMI

At 80% AMI

At 50% AMI

At Extremely

Low Income

33

55

90

99

THE GAP A SHORTAGE OF AFFORDABLE HOMES, 2023

NATIONAL LOW INCOME HOUSING COALITION

6

apparent shortage for renters with incomes above

50% of AMI can be explained by the signicant

shortage of aordable and available rental homes

for those with incomes below 50% of AMI.

Box 2 illustrates the incremental change in the

number of renters at increasing levels of income,

alongside the incremental increase in the number

of rental homes that are aordable and available.

e infographic shows how the cumulative shortage

shrinks signicantly at incomes between 51% and

80% of AMI.

e shortage of aordable and available homes is

most severe for extremely low-income renters, for

whom there are only 3.7 million aordable and

available units for 11.0 million households. is

group faces a shortage of 7.3 million aordable and

available homes. e second row in Box 2 illustrates

that an additional 6.8 million renter households

have incomes between extremely low-income and

50% of AMI and that an additional 6.1 million

rental homes become aordable and available to

households with incomes below 50% of AMI. As

a result, the cumulative shortage of aordable and

available rental homes increases by 0.7 million to

8.0 million.

e cumulative shortage decreases at higher levels of

income. Expanding the number of renter households

from those with incomes less than 50% of AMI to

include all those earning less than 80% of AMI adds

9.2 million households and 14.6 million aordable

and available rental homes to the cumulative totals.

Not all 14.6 million units are available to households

specically with incomes between 51% and 80%

of AMI, because they are occupied by renters

with incomes below 50% of AMI, but the overall

shortage of aordable and available rental homes

decreases by 5.4 million to 2.6 million. At median

income, the cumulative shortage nearly disappears.

e bars in Figure 4 represent the incremental

change in the cumulative shortage at each step up in

income. e most severe shortage of aordable and

available housing is faced by extremely low-income

renters. e dashed line represents the cumulative

shortage of aordable and available homes, which

eventually becomes a cumulative surplus for higher-

income renters. Each point on the line corresponds

There are 44.1 million renter households…

…and 46.0 million rental units with complete

kitchen and plumbing.

ALL INCOMES

< 80% AMI

< 100% AMI

< 50% AMI

EXTREMELY LOW-INCOME

An additional 9.2 million renter

households have low incomes…

…and an additional 14.6 million

affordableunits are available to

renters with incomes below 80% of

AMI.

The cumulative shortage of rental

units declines to 2.6 million,

because more affordable and

available units than households are

added to the cumulative totals.

The cumulative shortage of rental

units shrinks to 200,000.

An additional 4.6 million renter

households have moderate

incomes between 80% and 100%

of AMI…

…and an additional 7.0 million

affordable units are available to

renters with incomes below 100%

AMI.

Overall, there are 44.1 million rental

households and 46.0 million rental

units.

An additional 12.5 million renter

households have above-median

incomes…

…and 14.6 million more units are

affordable to renters with

above-median incomes.

Among these 44.1 million renter

households, 11.0 million have

extremely low incomes…

…but only 3.7 millionrentalunits

areaffordable and available to

extremely low-income house-

holds.

At this income level, renters face a

shortage of 7.3 million rental units.

An additional 6.8 million renter

households have very low-in-

comes…

…and an additional 6.1 million

units are affordable and available

to renters with incomes below 50%

of area median income (AMI).

The shortage of rental units increas-

es to 8.0 million, because more

households than affordable and

available rental units are added to

the cumulative totals.

44.1

46.0

BOX 2: INCREMENTAL CHANGES TO THE SHORTAGE OF AFFORDABLE AND

AVAILABLE HOUSING BY INCOME LEVEL

7

NATIONAL LOW INCOME HOUSING COALITION

THE GAP A SHORTAGE OF AFFORDABLE HOMES, 2023

FIGURE 4: THE MOST SEVERE SHORTAGE OF AFFORDABLE AND AVAILABLE

HOUSING IS FOR EXTREMELY LOW-INCOME RENTERS

INCREMENTAL CHANGE TO SURPLUS (DEFICIT) OF AFFORDABLE AND AVAILABLE RENTAL HOMES. 2021 (IN MILLIONS)

Source: 2021 ACS PUMS

-7.3

-0.7

5.4

2.4

2.1

-8.0

-2.6

-0.2

1.9

Extremely

Low-Income (ELI)

Very Low-Income

(ELI-50% of AMI)

Low-Income

(51-80% of AMI)

Middle Income

(81-100% of AMI)

Above Median

Income

(>100% of AMI)

Cumulative Surplus (Deficit) of Affordable

and Available Rental Homes

Surplus (Deficit) Within Income Band

There are 44.1 million renter households…

…and 46.0 million rental units with complete

kitchen and plumbing.

ALL INCOMES

< 80% AMI

< 100% AMI

< 50% AMI

EXTREMELY LOW-INCOME

An additional 9.2 million renter

households have low incomes…

…and an additional 14.6 million

affordableunits are available to

renters with incomes below 80% of

AMI.

The cumulative shortage of rental

units declines to 2.6 million,

because more affordable and

available units than households are

added to the cumulative totals.

The cumulative shortage of rental

units shrinks to 200,000.

An additional 4.6 million renter

households have moderate

incomes between 80% and 100%

of AMI…

…and an additional 7.0 million

affordable units are available to

renters with incomes below 100%

AMI.

Overall, there are 44.1 million rental

households and 46.0 million rental

units.

An additional 12.5 million renter

households have above-median

incomes…

…and 14.6 million more units are

affordable to renters with

above-median incomes.

Among these 44.1 million renter

households, 11.0 million have

extremely low incomes…

…but only 3.7 millionrentalunits

areaffordable and available to

extremely low-income house-

holds.

At this income level, renters face a

shortage of 7.3 million rental units.

An additional 6.8 million renter

households have very low-in-

comes…

…and an additional 6.1 million

units are affordable and available

to renters with incomes below 50%

of area median income (AMI).

The shortage of rental units increas-

es to 8.0 million, because more

households than affordable and

available rental units are added to

the cumulative totals.

44.1

46.0

BOX 2: INCREMENTAL CHANGES TO THE SHORTAGE OF AFFORDABLE AND

AVAILABLE HOUSING BY INCOME LEVEL

to the dierence between the cumulative number

of renters and the cumulative number of aordable

and available homes for households at or below that

income level.

e ACS, on which our analysis is based, does

not capture the number of people experiencing

homelessness, so we underestimate the shortage of

aordable and available housing. Approximately

582,500 people were experiencing homelessness on

a given night in 2022 (U.S. Department of Housing

and Urban Development, 2022). Of this number,

421,392 were individuals and 161,070 were people

in approximately 51,000 families, meaning that

an additional 472,392 homes would be needed to

house all people experiencing homelessness. e real

shortage of rental homes aordable and available to

extremely low-income households is therefore closer

to 7.8 million. Even this estimate is conservative,

as it does not account for individuals and families

that are doubled-up with others due to a lack of

other housing options. Recent estimates nd that an

additional 3.7 million individuals are experiencing

doubled-up homelessness (Richard et al., 2022).

Recent Declines in Affordable and

Available Rental Homes

ree factors could explain the increase in the

shortage of aordable and available rental homes

for extremely low-income renters from 6.8 million

to 7.3 million between 2019 and 2021: an increase

in the number of extremely low-income renters, a

decrease in the number of apartments aordable to

extremely low-income renters, and an increase in the

number of higher-income renters occupying units

aordable to extremely low-income renters.

e number of extremely low-income renter

households increased from 10.8 million in 2019

to 11.0 million in 2021. is increase may be due,

at least in part, to greater unemployment and

employment volatility following the onset of the

COVID-19 pandemic. In 2021, 6.3% of the civilian

labor force was unemployed, compared to 4.5%

in 2019 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2022a; U.S. Census

Bureau, 2020). Workers in low-wage occupations

were particularly vulnerable to job loss and faced

barriers to re-entering the workforce, such as the

slow recovery of jobs in sectors like leisure and

hospitality and potentially greater fear of contracting

COVID-19 given that low-wage occupations are

more likely to require face-to-face contact with the

public (Bateman and Ross, 2021).

e worsening shortage is also a result of a

decline in the number of aordable rental homes

for extremely low-income renters. Median rents

skyrocketed in 2021, increasing 18% between

January 2021 and January 2022 (Apartment List,

2022). At the same time, rental vacancy rates hit

lows not seen since the 1980’s (U.S. Census Bureau,

2023). Not surprisingly, the number of rental homes

aordable to extremely low-income renters declined

from 7.4 million to 7.0 million between 2019 and

2021.

e decrease in aordable and available rental

homes for extremely low-income renters does not

THE WORSENING

SHORTAGE IS

ALSO A RESULT

OF A DECLINE

IN THE NUMBER

OF AFFORDABLE

RENTAL HOMES FOR

EXTREMELY LOW-

INCOME RENTERS.

9

NATIONAL LOW INCOME HOUSING COALITION

THE GAP A SHORTAGE OF AFFORDABLE HOMES, 2023

appear to be the result of more higher-income

households moving into low-cost units that would

otherwise be aordable and available to extremely

low-income renters. Between 2019 and 2021, the

number of higher-income households living in

rental homes aordable to extremely low-income

renters declined from 3.4 million to 3.3 million.

HOUSING COST BURDENS

Households are considered housing cost-burdened

when they spend more than 30% of their incomes

on rent and utilities. ey are considered severely

cost-burdened when they spend more than 50%

of their incomes on their housing. Because cost-

burdened households spend a higher share of their

income on housing, they have less to spend on other

necessities, such as food, childcare, transportation,

and healthcare.

Extremely low-income renters are far more likely

than others to experience severe housing cost-

burden. Eighty-six percent of all extremely low-

income renters experience housing cost-burden and

73% are severely cost-burdened (Figure 5). Renters

with higher incomes are far less likely to experience

severe cost-burdens. Seventy-seven percent of very

low-income households are housing cost-burdened,

but far fewer (34%) experience severe cost-burdens

compared to extremely low-income renters. e

FIGURE 5: EXTREMELY LOW-INCOME HOUSEHOLDS DISPROPORTIONATELY

EXPERIENCE SEVERE HOUSING COST BURDENS

RENTER HOUSEHOLDS WITH HOUSING COST BURDENS BY INCOME GROUP, 2021

Source: 2021 ACS PUMS

86%

2%

47%

8%

21%

6%

1%

34%

77%

73%

Extremely

Low-Income

Very Low-Income Low-Income Middle Income Above Median

Income

Cost Burden

Severe Cost Burden

EXTREMELY

LOW-INCOME

RENTERS ARE

FAR MORE LIKELY

THAN OTHERS

TO EXPERIENCE

SEVERE HOUSING

COST-BURDEN.

THE GAP A SHORTAGE OF AFFORDABLE HOMES, 2023

NATIONAL LOW INCOME HOUSING COALITION

10

share of low-income, middle-income, and above-

median-income renters who are severely cost-

burdened is 8%, 2%, and 1%, respectively.

Of the 11.3 million severely cost-burdened renter

households, 8.1 million, or 72%, are extremely low-

income, 2.3 million are very low-income, 713,000

are low-income, and 188,000 are middle- or higher-

income (Figure 6). Combined, extremely low-, very

low-, and low-income households account for 98% of

all severely cost-burdened renters.

Severely cost-burdened extremely low-income

renters have little, if any, money remaining for other

necessities after paying their rent. An extremely

low-income family of four with a monthly income of

4 is amount served as the poverty guideline in the 48 contiguous U.S. states and the District of Columbia for a four-person family in 2022.

5 e weighted average of two-bedroom fair market rents (FMRs) by FMR area (NLIHC, 2022a).

$2,312

4

paying the average two-bedroom fair market

rent of $1,342

5

only has $970 left each month

to cover other expenses (National Low Income

Housing Coalition, 2022a). e U.S. Department

of Agriculture’s (USDA) thrifty food budget for

a family of four (two adults and two school-aged

children) estimates a family needs to spend $967

per month to cover food alone, leaving $3 for

transportation, childcare, and all other necessities

(U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2022). Struggles to

aord basic necessities have worsened over the last

two years, as ination has impacted prices for nearly

all household goods (Bureau of Labor Statistics,

2023a).

Extremely Low-Income Very Low-Income Low-Income Middle-Income Above Median Income

Source: NLIHC tabulations of 2021 ACS PUMS data.

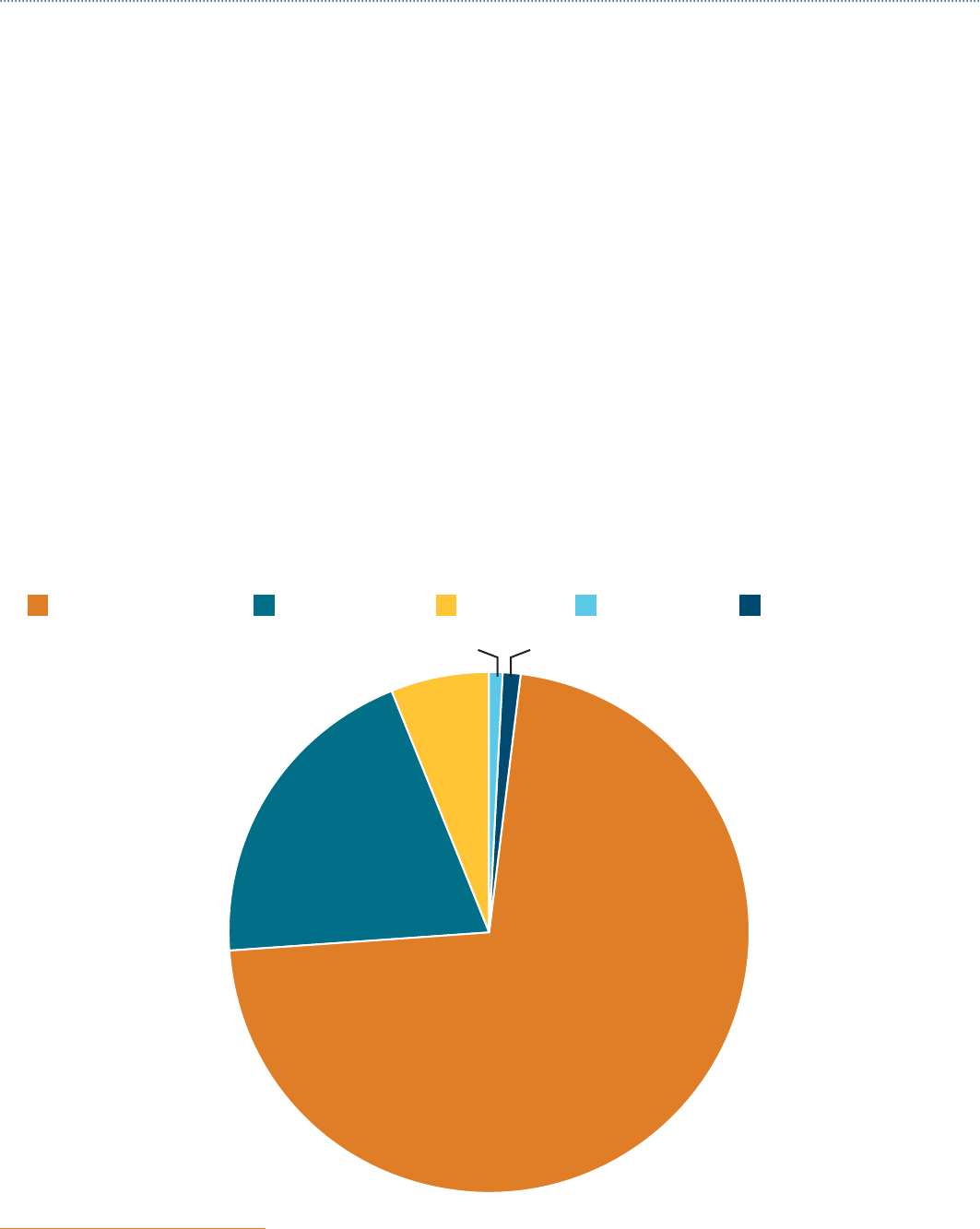

FIGURE 6: EXTREMELY LOW-INCOME RENTERS MAKE UP MAJORITY OF

SEVERELY COST-BURDENED RENTERS

SEVERELY COST-BURDENED RENTER HOUSEHOLDS BY INCOME GROUP, 2021

72%

20%

6%

1%

1%

11

NATIONAL LOW INCOME HOUSING COALITION

THE GAP A SHORTAGE OF AFFORDABLE HOMES, 2023

e residual income approach to measuring housing

aordability is another way to identify households

who are overly burdened by their housing costs. is

approach assesses whether households have enough

income left for non-housing basic necessities after

paying their rent. Research indicates that 100% of

renters with annual household incomes less than

$30,000, and 81% of renters with annual household

incomes between $30,000 and $44,999, were unable

to aord other basic necessities after they paid

for their housing (Airgood-Obrycki et al., 2022).

Families with children are more likely to experience

residual income cost burden than single individuals

and couples without children.

WHO ARE EXTREMELY LOW-

INCOME RENTERS?

Most extremely low-income renters either work in

low-wage jobs or may be unable to work. ey are

more likely than other renters to be seniors or have

disabilities. Among extremely low-income renter

householders, 35% are in the labor force, 30% are

seniors, 18% have a disability, and 7% are students

or single-adult caregivers to young children or

household members with a disability (Figure 7).

In 2021, 39% of extremely low-income renter

households in the labor force worked at least

Note: Mutually exclusive categories applied in the following order: senior, disabled, in labor force, enrolled in school, single adult caregiver

of a child under 7 or of a household member with a disability, and other. Senior means householder or householder’s spouse (if applicable)

is at least 62 years of age. Disabled means householder and householder’s spouse (if applicable) are younger than 62 and at least one of

them has a disability. Working hours refers to the number of hours usually worked by householder and householder's spouse (if applicable).

School means householder and householder's spouse (if applicable) are enrolled in school. Thirteen percent of extremely low-income

renter households include a single adult caregiver, 49% of whom usually work more than 20 hours per week. Ten percent of extremely

low-income renter householders are enrolled in school, 47% of whom usually work more than 20 hours per week. Source: 2021 ACS PUMS

FIGURE 7: MOST EXTREMELY LOW-INCOME HOUSEHOLDERS ARE IN LABOR

FORCE, ARE SENIORS, OR HAVE A DISABILITY

EXTREMELY LOW-INCOME RENTER HOUSEHOLDS

40+ hours / week

20 to 39 hours / week

< 20 hours / week

Unemployed

30%

39%

11%

20%

In Labor Force

35%

3%

School

4%

Other

11%

Disabled

18%

Senior

30%

Single non-disabled non-elderly caregiver

of person w/ disability or young child

THE GAP A SHORTAGE OF AFFORDABLE HOMES, 2023

NATIONAL LOW INCOME HOUSING COALITION

12

40 hours per week and 30% worked between 20

and 39 hours per week. Often, though, low-wage

employment does not provide income adequate

to aord housing. e national average wage that

must be earned by a full-time worker to aord a

modest one-bedroom and two-bedroom apartment

is $21.25 and $25.82 per hour, respectively (National

Low Income Housing Coalition, 2022a). Eleven of

the 25 largest occupations in the country, including

home health aides, janitors, nursing assistants, and

food servers pay a median wage that is far less than

this. e average per-hour wage needed to aord

a modest two-bedroom apartment is at least $10

more than the median wages provided by these

occupations.

Beyond low wages, extremely low-income workers

experienced elevated rates of unemployment

at the height of the pandemic – a result of the

disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on workers

in low-wage occupations. Between 2019 and 2021,

unemployment among extremely low-income

renters in the labor force increased from 13% to

20%. Low-wage industries make up 30% of all

jobs nationally but accounted for 59% of jobs lost

between February 2020 and October 2021 (Center

on Budget and Policy Priorities, 2022).

Employment has improved signicantly since mid-

2020, with the national unemployment rate falling

from 10.2% in July 2020 to 3.4% in January 2023

(Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2023c). Yet even as

many low-wage renters regain employment, their

wages remain insucient to aord housing. At the

same time, not all wage increases have kept pace

with recent high rates of ination. Households

earning less than $20,000 per year saw their costs

of living increase at three times the rate of their

wage growth in 2021 (Arnon, He, & Sun, 2022). In

comparison, households earning more than $60,000

annually saw their incomes increase at a higher rate

than their costs of living. Meanwhile, during 2022,

wage earners nationally experienced a 1.7% decrease

in their real wages (Bureau of Labor Statistics,

2023d).

While Figure 7 categorizes extremely low-income

renters into mutually exclusive groups for simplicity,

the lived experience of these renters often involves

juggling multiple responsibilities, like working to

make ends meet at the same time as serving as a

primary caretaker or pursuing further education in

school. More than 13% of extremely low-income

renters are single-adult caregivers of a young child

or of a household member with a disability. Nearly

60% of these caregivers also participate in the

labor force, with 25% percent working at least 40

hours per week and another 24% typically working

between 20 and 39 hours per week. Ten percent of

extremely low-income renters are enrolled in school,

29% of whom usually work 20 to 39 hours per week,

and another 18% work at least 40 hours per week.

Without housing assistance or increases in their

hourly wages, they cannot rely on their work hours

to aord their homes.

RACIAL DISPARITIES AMONG

EXTREMELY LOW-INCOME

RENTERS

e shortage of aordable and available housing

disproportionately aects Black, Latino, and

Native and Alaska Native households, as these

households are both more likely to be renters and

to have extremely low incomes. ey are more than

twice as likely as white households to be extremely

low-income renters. For example, 57% of Black

households are renters and 19% are extremely

low-income renters. Fifty-two percent of Latino

households are renters and 14% are extremely

low-income renters. In contrast, 27% of white

households are renters and 6% are extremely low-

income renters (Figure 8).

13

NATIONAL LOW INCOME HOUSING COALITION

THE GAP A SHORTAGE OF AFFORDABLE HOMES, 2023

ese disparities are the

product of historical

and ongoing injustices

that have systematically

disadvantaged people of

color, often preventing them

from owning a home and

signicantly limiting wealth

accumulation. Some of these

injustices persist to this day,

including discrimination

in both the housing and

labor markets. ough many

obviously racist institutions

and practices, like slavery

and de jure segregation, have

ended, our society has failed

to eliminate discriminatory

practices and redress the

economic inequalities

produced by racist policies

(Box 3).

Homeowners Renters Extremely Low-Income Renters

FIGURE 8: HOUSEHOLDS OF COLOR MORE LIKELY THAN WHITE

HOUSEHOLDS TO BE RENTERS AND HAVE EXTREMELY LOW INCOMES

SHARE OF HOUSEHOLDS BY TENURE AND RACE

Source: 2021 ACS PUMS

Black, non-Latino Latino American Indian

or Alaska Native

Asian White, non-Latino

27%

57%

38%

45%

52%

19%

62%

55%

48%

43%

6%

9%

17%

14%

73%

BOX 3: HISTORICAL DRIVERS OF

HOUSING INEQUITY

Decades of racial discrimination by real estate agents, banks, insurers, and the federal

government have made homeownership difcult to obtain for people of color. Many

factors kept people of color from being able to purchase homes through the middle

of the twentieth century: pervasive refusal of whites to live in racially integrated

neighborhoods, physical violence targeting people of color who tried to integrate

(which was often tolerated by police), restrictive covenants forbidding home sales to

Black buyers who would integrate neighborhoods (some of which were mandated by

the Federal Housing Administration), and federal housing policy that denied borrowers

access to credit in minority neighborhoods (Massey & Denton, 1993; Coates, 2014;

Rothstein, 2017). Being denied the ability to purchase homes also meant that people of

color did not benet from the appreciation in the value of these homes, a major driver of

the racial wealth gap.

While overt discrimination was outlawed by the “Fair Housing Act of 1968,” subtler forms

of housing discrimination continue to constrain the options of people of color. HUD’s fair

housing tests in 28 metropolitan areas in 2013 found that Black homebuyers were shown

17.7% fewer homes than white homebuyers with the same qualications and preferences

(U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, 2013). More recent fair housing

investigations show similar unfavorable treatment of people of color, including being

shown fewer homes and not being given the same information as whites (Chicago

Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights, 2018; Choi, Herbert, Winslow, & Browne, 2019).

Today’s credit scoring system and lending practices also continue to serve as barriers to

minority homeownership (Rice & Swesnik, 2012; Bartlett et al., 2019).

THE GAP A SHORTAGE OF AFFORDABLE HOMES, 2023

NATIONAL LOW INCOME HOUSING COALITION

14

e impacts of sustained discrimination and

oppression show up not just in homeownership

disparities but also in income disparities across

racial and ethnic groups. e 2021 ACS indicates

that the median annual income of Black households

was $46,774, nearly $30,000 less than the median

income of white households ($75,412). e median

annual income of Latino households was $60,566,

and the median annual income for American Indian

and Alaska Native households was $53,149. ese

disparities reect the fact that Black and Latino

workers are less likely to work in sectors with higher

median wages and tend to be paid less than white

workers even within the same occupations (

Bureau

of Labor Statistics, 2023b; Wilson, Miller, & Kassa,

2021)

.

Renters of color are much more likely to be housing

cost-burdened: 55% of Black renters and 52% of

Latino renters are housing cost-burdened, compared

to 44% of white renters (Figure 9). Nearly one-third

of Black renters but only 23% of white renters are

severely cost-burdened, spending more than half of

their income on housing. Racial disparities in cost

burdens can be partially explained by income, as the

disparity shrinks when looking only at extremely

low-income renters. Extremely low-income renters

who are Latino, Black, and white experience housing

cost-burdens at a rate of 88%, 87%, and 85%,

respectively (Figure 9), and severe cost-burdens at a

rate of 75%, 74%, and 72%.

HOUSING SHORTAGES FOR

EXTREMELY LOW-INCOME

RENTERS BY GEOGRAPHY

Shortages by State

e aordable housing crisis aects communities

nationwide, as no state has an adequate supply of

rental housing aordable and available for extremely

low-income households (Figure 10 and Appendix

A). e absolute shortage ranges from 10,215 rental

homes in Wyoming to nearly 1 million in California.

Extremely low-income renters face the most severe

shortages in Nevada, Oregon, Florida, California,

Arizona, and Texas. Nevada has only 17 aordable

and available rental homes for every 100 extremely

low-income renter households. Oregon and Florida

both have only 23, followed by California and

Arizona (24/100). e states with the greatest

relative supply of aordable and available rental

homes for extremely low-income renters still have

signicant shortages. e states with the lowest

relative shortages are South Dakota, with 58

aordable and available rental homes for every 100

extremely low-income renter households, Rhode

Island (53/100), Mississippi (51/100), West Virginia

(50/100), and North Dakota (50/100).

In every state, more than half of extremely low-

income renters are severely housing cost-burdened.

In 12 states, more than three-quarters of extremely

low-income renters are severely housing cost-

THE STATES WITH THE GREATEST RELATIVE

SUPPLY OF AFFORDABLE AND AVAILABLE

RENTAL HOMES FOR EXTREMELY LOW-INCOME

RENTERS STILL HAVE SIGNIFICANT SHORTAGES.

15

NATIONAL LOW INCOME HOUSING COALITION

THE GAP A SHORTAGE OF AFFORDABLE HOMES, 2023

FIGURE 9: BLACK AND LATINO RENTERS EXPERIENCE HIGHER RATES OF

HOUSING COST-BURDEN THAN WHITE RENTERS

COST-BURDEN BY RACE AND ETHNICITY

COST-BURDEN AMONG EXTREMELY LOW-INCOME RENTERS, BY RACE AND ETHNICITY

Cost Burden Severe Cost Burden

55%

32%

52%

45%

44%

42%

41%

28%

26%

23%

25%

21%

Black, non-Latino Latino American Indian

or Alaska Native

AsianWhite,

non-Latino

Other

Black, non-Latino Latino American Indian

or Alaska Native

AsianWhite,

non-Latino

Other

Cost Burden Severe Cost Burden

87%

74%

88%

77%

85%

85%

85%

75%

60%

72%

72%

75%

Source: 2021 ACS PUMS

THE GAP A SHORTAGE OF AFFORDABLE HOMES, 2023

NATIONAL LOW INCOME HOUSING COALITION

16

burdened, with the largest shares in Nevada (86%),

Florida (83%), Oregon (80%), Arizona (80%), and

Texas (79%). Maine and Rhode Island have the

smallest, but still signicant, percentage of extremely

low-income renters with severe cost burdens, with

52% and 60%, respectively.

Within each state, the shortage of aordable and

available rental homes starts to dissipate when

moving higher up the income ladder. For example,

all states and the District of Columbia have a

shortage of aordable and available rental housing

for extremely low-income renters, and all but one

state has a shortage for all renters whose household

incomes fall below 50% of AMI. irty states and

D.C. have a cumulative shortage for all renters

with household incomes below 80% of AMI. e

cumulative shortage of housing in most states

disappears once all households below 100% of AMI

are added together. e fact that there are enough

homes for higher-income households obscures the

shortage for the lowest-income households. Still,

nine states with high-cost metropolitan regions –

California, Florida, Hawaii, Massachusetts, Nevada,

New Jersey, New York, Oregon, and Vermont – have

cumulative shortages for all renters whose household

incomes fall at or below 100% of AMI.

FIGURE 10: RENTAL HOMES AFFORDABLE AND AVAILABLE

PER 100 EXTREMELY LOW INCOME RENTER HOUSEHOLDS BY STATE

Note: Extremely low-income (ELI) renter households have incomes at or below the poverty level or 30% of the area median

income. Source: NLIHC tabulations of 2021 1-Year ACS PUMS Data.

ME

49

NY

32

PA

38

VA

32

WV

50

OH

40

IN

39

MI

36

IL

34

WI

35

MN

38

IA

40

MO

44

AR

47

LA

39

TX

25

OK

39

KS

40

NE

38

ND

50

SD

58

MT

45

ID

38

WA

28

OR

23

CA

24

AK

35

HI

34

WY

41

CO

26

UT

33

NV

17

AZ

24

NM

36

NC

39

TN

41

KY

46

SC

42

GA

34

AL

49

MS

51

FL

23

30 or Fewer

Between 31 and 40

Between 41 and 45

More than 45

MA–44

RI–53

CT–37

NJ–31

DE–27

MD–30

DC–40

NH–38

VT–35

17

NATIONAL LOW INCOME HOUSING COALITION

THE GAP A SHORTAGE OF AFFORDABLE HOMES, 2023

Shortages in the 50 Largest

Metropolitan Areas

Every major metropolitan area in the U.S. has a

shortage of aordable and available rental homes

for extremely low-income renters (Appendix B). Of

the 50 largest metropolitan areas, extremely low-

income renters face the most severe shortages in

Las Vegas, NV (where there are 14 aordable and

available rental homes for every 100 extremely low-

income renter households), followed by Orlando,

FL, Dallas, TX, Austin, TX, Houston, TX, San

Diego, CA, and Phoenix, AZ (Table 1).

e largest metropolitan areas with the least severe

shortages of rental homes aordable and available

to extremely low-income renters are Providence, RI

(where there are 48 homes for every 100 extremely

low-income renter households), Pittsburgh, PA,

Boston, MA, Kansas City, MO, Cincinnati, OH,

and Cleveland, OH. While these areas have the

least severe shortages, they each still have fewer

than half the supply of aordable and available

homes needed for extremely low-income renters

(Table 1).

High rates of severe cost burden persist across every

metropolitan area. Not surprisingly, severe cost

burdens are most prevalent in areas with extreme

shortages of aordable and available housing. More

than 85% of extremely low-income renters in Las

Vegas, Orlando, Austin, and Dallas experience

severe housing cost burdens. Metropolitan areas

with less severe shortages of aordable and available

rental housing have lower yet still high rates of

severe cost burdens. In every major metropolitan

area, more than 60% of extremely low-income

renters living in the area are severely cost-burdened.

TABLE 1: LEAST AND MOST SEVERE SHORTAGES OF RENTAL HOMES

AFFORDABLE TO EXTREMELY LOW-INCOME HOUSEHOLDS ACROSS THE 50

LARGEST METROPOLITAN AREAS

LEAST SEVERE MOST SEVERE

Metropolitan Area

Affordable

and Available

Rental Homes

per 100 Renter

Households Metropolitan Area

Affordable

and Available

Rental Homes

per 100 Renter

Households

Providence-Warwick, RI-MA 48 Las Vegas-Henderson-Paradise, NV 14

Pittsburgh, PA 48 Orlando-Kissimmee-Sanford, FL 15

Boston-Cambridge-Newton, MA-NH 44 Dallas-Fort Worth-Arlington, TX 16

Kansas City, MO-KS 39 Austin-Round Rock-Georgetown, TX 16

Cincinnati, OH-KY-IN

38 Houston-The Woodlands-Sugar Land, TX 19

Cleveland-Elyra, OH 38 San Diego-Chula Vista-Carlsbad, CA 19

St. Louis, MO-IL 37 Phoenix-Mesa-Chandler, AZ 19

Minneapolis-St. Paul-Bloomington, MN-WI 36

Los Angeles-Long Beach-Anaheim, CA

20

Louisville/Jefferson County, KY-IN 35 Riverside-San Bernardino-Ontario, CA 20

Hartford-East Hartford-Middletown, CT 35 Jacksonville, FL 21

Tampa-St. Petersburg-Clearwater, FL 21

Source: 2021 ACS PUMS

THE GAP A SHORTAGE OF AFFORDABLE HOMES, 2023

NATIONAL LOW INCOME HOUSING COALITION

18

e lack of housing assistance is one factor driving

severe housing cost burdens among extremely

low-income renters. Figure 11 shows the inverse

relationship between severe cost burdens and

HUD-assisted housing, which includes public

housing, Housing Choice Vouchers, and project-

based rental assistance. As the share of rental

housing that is HUD-assisted increases, the share

of extremely low-income renters who are severely

cost-burdened decreases. More than half of the

variation in rates of severe cost burdens across the

largest metropolitan areas can be explained by

the share of rental housing that is HUD-assisted.

is relationship exists even after considering

rental vacancy rates, the share of rental housing in

multifamily buildings, and the age of the housing

stock.

In Boston, for example, 64% of extremely low-

income renter households are severely cost-

burdened, while HUD-assisted rental housing

represents a relatively high share (19%) of the

rental stock. Massachusetts also operates its own

state-funded public housing programs, which

provide thousands of additional subsidized units

in the Boston metropolitan area (Massachusetts

Department of Housing and Community

Development, 2022). In contrast, 89% of extremely

low-income renters in the Las Vegas and Orlando

metropolitan areas are severely cost-burdened, while

HUD-assisted housing represents only 5% and 3%

of the rental housing stock, respectively.

19

NATIONAL LOW INCOME HOUSING COALITION

THE GAP A SHORTAGE OF AFFORDABLE HOMES, 2023

FIGURE 11: GREATER HUD-ASSISTED SHARE OF RENTAL HOUSING

ASSOCIATED WITH LOWER SHARE OF SEVERELY COST-BURDENED

EXTREMELY LOW-INCOME RENTERS

HUD-ASSISTED SHARE OF RENTAL STOCK BY SEVERELY COST-BURDENED SHARE OF

EXTREMELY LOW-INCOME RENTERS

0%

5%

10%

15%

20%

25%

50% 55% 60% 65% 70% 75% 80% 85% 90% 95% 100%

Source: 2021 ACS PUMS and HUD Picture of Subsidized Households

HUD-Assisted Share of Rental Stock

Share of Severely Cost-Burdened ELI Renter Households

Providence, RI

Las Vegas, NV

Orlando, FL

Boston, MA

R

2

= 0.5145

LOCAL SOLUTIONS TO

AFFORDABLE HOUSING

DEVELOPMENT

Eliminating the shortage of aordable and available

rental housing requires a combination of local, state,

and federal solutions. Local eorts like land use and

zoning reform are often necessary to allow more

rental housing development, including aordable

housing, but they are insucient on their own

to remedy the severe shortage of aordable and

available housing for the lowest-income tenants.

Exclusionary zoning that favors the development of

single-family homes, limits high-density housing,

and stipulates other restrictions like minimum lot

sizes, set-backs, and parking requirements severely

limits the amount and types of new housing that can

be built. ese regulations can constrain the supply

of housing and raise prices because they typically

increase the amount of land needed for each home.

Restrictive zoning regulations limit rental housing,

particularly multifamily developments (Schuetz,

2009; Pendall, 2000). Recent research nds that

in states categorized as “exclusionary” – where

regulations make it dicult to up-zone properties

to allow apartments – renters pay an additional

$122 per month in rent (Landis & Reina, 2021).

Exclusionary zoning regulations also exacerbate

segregation by prohibiting development of housing

that may be more aordable to non-white residents.

One study found the Black and Latino shares of the

population are 3.4 and 3.5 percentage points greater

in blocks zoned for multifamily housing than in

contiguous blocks zoned for single-family housing

(Resseger, 2013).

Zoning restrictions are widespread. A 2019 analysis

found that up to 75% of residential land across many

cities is zoned exclusively for detached single-family

homes (Badger & Bui, 2019). Additionally, a survey

of suburban land use regulations found minimum lot

size requirements are more widely used now than 10

years ago and are more severe (Gyourko et al., 2019).

Between 2006 and 2018, the share of suburban

municipalities with minimum lot size requirements

increased from 83% to 96%, and minimum sizes of

one or more acres became more common.

Some cities and states have enacted zoning reforms

to allow somewhat higher-density housing by-right,

meaning no special variance or zoning exception

is needed. Such requests for a variance that

require public notices and hearings can be time-

consuming and create opportunities for opponents

LOCAL EFFORTS LIKE LAND USE AND ZONING

REFORM ARE OFTEN NECESSARY TO ALLOW

MORE RENTAL HOUSING DEVELOPMENT,

INCLUDING AFFORDABLE HOUSING, BUT THEY

ARE INSUFFICIENT ON THEIR OWN TO REMEDY

THE SEVERE SHORTAGE OF AFFORDABLE

AND AVAILABLE HOUSING FOR THE LOWEST-

INCOME TENANTS.

THE GAP A SHORTAGE OF AFFORDABLE HOMES, 2023

NATIONAL LOW INCOME HOUSING COALITION

20

to successfully stop new development. ese

density-related reforms are too recent to permit

full evaluation of their impact, and allowing higher

densities does not immediately guarantee an increase

in the general housing supply or an increase in rental

housing. At a minimum, however, these reforms

are necessary because they provide opportunities

for higher-density housing to be built in order to

encourage a greater supply of housing and improve

aordability.

Local eorts to support housing development

are also necessary for increasing the aordable

housing supply. State and local government housing

programs, like housing trust funds and aordable

housing bonds, often fund development targeted

at renters with specic income levels or at special

populations (National Low Income Housing

Coalition, 2022b). Ideally, these programs would

direct resources to housing for renters with the

greatest needs – those with the lowest incomes. Both

zoning reforms and local housing supports, while

extremely important, are limited in their ability

to bolster aordable housing at scale, however,

due to the price and complexity of aordable

housing development. Most cities simply do not

have adequate resources of their own to develop

aordable housing at scale without state and federal

resources.

Absent public subsidy, private market development

typically targets the higher-priced end of the

housing market and, on its own, rarely produces

new rental housing aordable to the lowest-income

households. According to the Joint Center for

Housing Studies (2022b), the typical monthly

asking rent for new multifamily units was $1,740

in 2021. In comparison, the most a family of four

with an income below the poverty guideline in

the continental U.S. could aord in monthly rent

without experiencing a cost burden was $663

(National Low Income Housing Coalition, 2021).

New private-market development can, however,

result in a chain of household moves that benet

moderate and lower-income households through

ltering. eoretically, households with sucient

income move into the new housing, making

available their previous and older housing to other

households, who in turn leave behind even older

units, and so on. Eventually this process increases

the availability of the oldest (and lowest-cost) units

to low-income renters.

Filtering on its own, however, fails to provide an

adequate supply of housing for the lowest-income

renters. Even when ltering occurs as expected and

properties’ share of occupants with low incomes

increases with building age, the occupants are

typically housing cost-burdened (Myers & Park,

ABSENT PUBLIC SUBSIDY, PRIVATE MARKET

DEVELOPMENT TYPICALLY TARGETS THE

HIGHER-PRICED END OF THE HOUSING

MARKET AND, ON ITS OWN, RARELY PRODUCES

NEW RENTAL HOUSING AFFORDABLE TO THE

LOWEST-INCOME HOUSEHOLDS.

21

NATIONAL LOW INCOME HOUSING COALITION

THE GAP A SHORTAGE OF AFFORDABLE HOMES, 2023

2020). Too often, the operating cost of maintaining

older housing is more than what extremely low-

income renters can aord to pay in rent. For

example, the average monthly operating cost for

rental units was $520 in 2019, yet the average

extremely low-income household could only aord

a monthly rent of $283 (Bailey, 2022). Before rents

in older housing become low enough for extremely

low-income households to aord, owners in weak

markets likely have an incentive to either abandon

their housing or convert their property to a dierent

use if regulations permit. In strong markets,

owners have an incentive to upgrade or rehabilitate

their units and rent them at higher prices. Given

these limitations, federal solutions are necessary

to meaningfully address the aordable housing

shortage for the lowest-income renters.

FEDERAL POLICY SOLUTIONS

TO REDUCE THE SHORTAGE OF

AFFORDABLE HOMES

Eliminating the aordable housing shortage will

require a long-term federal commitment to investing

in new aordable housing, preserving aordable

rental homes that already exist, bridging the gap

between household incomes and rent through

universal rental assistance, providing emergency

assistance to stabilize renters when they experience

nancial shocks, and incentivizing reductions in

zoning regulations that limit aordable housing

development. Reductions in federal appropriations

for critical housing assistance programs that serve

renters with extremely low incomes will only

exacerbate our aordable housing

crisis and push even more families

into housing instability and

homelessness.

Budget cuts not only exacerbate

the problem but can generate

negative long-term eects that

are dicult to reverse. Increases

to HUD’s appropriations in

recent years, for example, have

not entirely made up for the cuts

experienced by HUD during the

rst years of budget caps under

the “Budget Control Act of

2011” (BCA). Between scal year

(FY) 2011 and FY2017, HUD

experienced seven consecutive years

of real budget cuts after accounting

for ination (Figure 12). HUD’s

cumulative appropriations during

this time were $27 billion less than

if HUD’s annual appropriations

had remained at FY2010 levels,

adjusted only for ination. Even

with signicant increases in

REDUCTIONS IN FEDERAL

APPROPRIATIONS FOR

CRITICAL HOUSING

ASSISTANCE PROGRAMS

THAT SERVE RENTERS

WITH EXTREMELY LOW

INCOMES WILL ONLY

EXACERBATE OUR

AFFORDABLE HOUSING

CRISIS AND PUSH EVEN

MORE FAMILIES INTO

HOUSING INSTABILITY

AND HOMELESSNESS.

THE GAP A SHORTAGE OF AFFORDABLE HOMES, 2023

NATIONAL LOW INCOME HOUSING COALITION

22

HUD’s appropriations in recent years, HUD’s

cumulative appropriations since FY2010 are still

slightly lower than if annual appropriations had

remained at FY2010 levels.

To fully address the shortage of aordable rental

housing for renters with extremely low incomes,

Congress must increase funding for both preserving

the stock of existing aordable housing and

increasing the supply of deeply aordable units.

Proposed legislation like the “American Housing

and Economic Mobility Act” (“S.1368” in the

117

th

Congress) would address the shortage of

aordable rental homes for extremely low-income

renters through an investment of nearly $45 billion

annually in the national Housing Trust Fund. e

bill also includes resources to repair public housing,

build or rehabilitate housing in tribal and Native

Hawaiian communities, and create and preserve

aordable homes in rural areas.

Congress must also increase resources for rental

assistance through Housing Choice Vouchers or

a renters’ tax credit. While vouchers alone do not

increase the supply of housing, they help address

the shortage of aordable and available units for

extremely low-income renters by allowing them

to aord moderately priced units. e “Ending

Homelessness Act of 2021” (“H.R.4496” in

the 117

th

Congress), for example, proposed to

establish a universal voucher program that would

enable all eligible households to receive rental

assistance. e bipartisan “Family Stability and

Opportunity Vouchers Act” (“S.1991” in the 117

th

Congress) would create 500,000 housing vouchers

specically targeted to low-income families with

young children and provide mobility counseling

services to help families nd housing options in

neighborhoods of their choice.

FIGURE 12: ANNUAL APPROPRIATIONS AND CUMULATIVE LOSS

(IN BILLIONS) FOR KEY HUD HOUSING PROGRAMS RELATIVE TO FY 2010

-$35

-$25

-$15

-$5

$5

$15

$25

-20%

-15%

-10%

-5%

0%

5%

10%

15%

Note: Adjusted for inflation. Key HUD housing programs include Tenant-Based Rental Assistance, Project-Based Rental Assistance, Public

Housing Capital and Operating Funds, HOME, Section 202, and Section 811.

-$27.1

-$17.0

-$5.6

FY11 FY12 FY13 FY14 FY15 FY16 FY17 FY18 FY19 FY20 FY21 FY22 FY23

-3%

-8%

-14%

-8%

-9%

-6%

-6%

2%

1%

5%

11% 11% 11%

Cumulative Loss Relative to Constant FY

2010 Funding Levels

Annual Appropriation Relative to FY 2010

23

NATIONAL LOW INCOME HOUSING COALITION

THE GAP A SHORTAGE OF AFFORDABLE HOMES, 2023

While long-term solutions are necessary to remedy

the persistent shortage of aordable and available

housing, short-term assistance is critical for lifting

up low-income households and protecting their

housing stability when they experience unexpected

nancial shocks. Economic precarity resulting from

the COVID-19 pandemic merely highlighted what

has long been known: the lowest-income families

are just one missed paycheck or unexpected expense

away from potential eviction or homelessness. e

U.S. Department of the Treasury’s Emergency

Rental Assistance program, which provided

$46.6 billion in emergency rental assistance for

households experiencing nancial distress during

the pandemic, provides a framework for what a

permanent version of this program could look

like (Aiken et al., 2022; National Low Income

Housing Coalition, 2022c). e “Eviction Crisis

Act” (“S.2182” in the 117

th

Congress) would help

establish a more permanent version of this program

by creating a national housing stabilization fund for

renters facing temporary nancial setbacks. Stopgap

funding for renters in need would help prevent

the many negative consequences associated with

evictions and homelessness, including mental stress,

loss of possessions, instability for children, and

increased diculty nding a new apartment.

Congress should enact federal renter protections

to address the power imbalance between landlords

and renters that puts renters at risk of housing

instability. ese protections include source-of-

income protections to prevent landlords from

discriminating against voucher holders, “just

cause” or “good cause” eviction standards, access

to legal counsel to put renters on more equal

legal footing with landlords, expungement of

eviction records, and limits on rent gouging.e

“Ending Homelessness Act of 2021” (“H.R.4496”

in the 117

th

Congress) and “Fair Housing

Improvement Act” (“S. 4485” and “H.R. 8213” in

the 117

th

Congress) would prohibit discrimination

based on source of income.Since 2021, state and

local governments have enacted or implemented

at least 172 renter protections; however, federal

legislation is needed to ensure renters in all

jurisdictions can benet from basic protections

(National Low Income Housing Coalition, 2023).

e federal government should also incentivize or

require local governments to eliminate restrictive

zoning rules that increase the cost of development

and limit housing supply for all renters. Bipartisan

legislation introduced in the previous Congress

included the “Yes in My Backyard Act” (“S.1614” in

the 117

th

Congress), or “YIMBY Act,” that would

require Community Development Block Grant

recipients to reduce barriers to aordable housing

development, including by enacting zoning reforms

that would allow for more multifamily housing

development.

CONCLUSION

Between 2019 and 2021, the pandemic’s negative

impact on employment and incomes, followed

by severe rent ination, worsened an aordable

housing crisis that was already acute. During this

period, the shortage of aordable and available

rental homes for renters with extremely low

incomes increased from 6.8 million to 7.3 million,

leaving the lowest-income renters with even fewer

places to turn. Despite an improving outlook

in early 2023, characterized by attening rental

ination and low unemployment, extremely low-

income renters will continue to struggle to nd

aordable homes.

Only sustained and signicant federal investments

in rental housing can ensure that the lowest-income

renters, who are disproportionately people of color,

have aordable homes. e new Congress must

recognize the urgent need for expanding our supply

of aordable rental housing, preserving the supply

that already exists, providing short-term assistance

THE GAP A SHORTAGE OF AFFORDABLE HOMES, 2023

NATIONAL LOW INCOME HOUSING COALITION

24

when nancial crises hit vulnerable households, and

protecting the housing stability of tenants.

ABOUT THE DATA

is report is based on data from the 2021

American Community Survey (ACS) Public Use

Microdata Sample (PUMS). e ACS is an annual

nationwide survey of approximately 3.5 million

addresses. It provides timely data on the social,

economic, demographic, and housing characteristics

of the U.S. population. PUMS contains individual

ACS questionnaire records for a subsample of

housing units and their occupants.

PUMS data are available for geographic areas

called Public Use Microdata Sample Areas

(PUMAs). Individual PUMS records were matched

to their appropriate metropolitan area or given

nonmetropolitan status using the Missouri Census

Data Center’s MABLE/Geocorr 2018 Geographic

Correspondence Engine. If at least 50% of a PUMA

was in a Core Based Statistical Area (CBSA), we

assigned it to the CBSA. Otherwise, the PUMA

was given nonmetropolitan status.

Households were categorized by their incomes

(as extremely low-income, very low-income, low-

income, middle-income, or above median income)

relative to their metropolitan area’s median family

income or state’s nonmetropolitan median family

income, adjusted for household sizes. Housing units

were categorized according to the income needed to

aord rent and utilities without spending more than

30% of income on these costs. e categorization

of units was done without regard to the incomes of

the current tenants. Housing units without complete

kitchens or plumbing facilities were not included in

the housing supply.

After households and units were categorized,

we analyzed the extent to which households in

each income category resided in housing units

categorized as aordable for that income level.

For example, we estimated the number of units

aordable for extremely low-income households that

were occupied by extremely low-income households

and by other income groups.

We categorized households into mutually exclusive

household types in the following order: (1)

householder or householder’s spouse were at least

62 years of age (seniors); (2) householder and

householder’s spouse (if applicable) were younger

than 62 and at least one of them had a disability

(disabled); and (3) householder and householder’s

spouse (if applicable) were younger than 62 and

at least one of them was in the labor force; (4)

householder and householder’s spouse (if applicable)

were enrolled in school; and (5) non-senior non-

disabled single adult was living with a young child

under seven years of age or person with disability.

More information about the ACS PUMS les is

available at https://www.census.gov/programs-

surveys/acs/microdata/documentation.html

FOR MORE INFORMATION

For further information regarding this report, please

contact NLIHC Senior Vice President for Research

Andrew Aurand at [email protected] or 202-662-

1530 x245.

REFERENCES

Aiken, C., Harner, I., Reina, V., Aurand, A., &

Yae, R. (2022). Emergency Rental Assistance (ERA)

during the pandemic: Implications for the design of

permanent ERA programs. National Low Income

Housing Coalition and Housing Initiative at

Penn. https://nlihc.org/sites/default/les/HIP_

NLIHC_2022_3-10_FINAL.pdf

25

NATIONAL LOW INCOME HOUSING COALITION

THE GAP A SHORTAGE OF AFFORDABLE HOMES, 2023

Airgood-Obrycki, W., Hermann, A., & Weeden,

S. (2022). “e rent eats rst”: Rental housing

unaordability in the United States. Housing Policy

Debate. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2021.20

20866

Apartment List. (2022). National-level historic

estimates (2017-present) [Data set]. Apartment List.

https://www.apartmentlist.com/research/category/

data-rent-estimates

Arnon, A., He, Z., & Sun, X. (2022). Did wages

keep up with ination in 2021? (2022). University

of Pennsylvania, Penn Wharton Budget Model.

https://budgetmodel.wharton.upenn.edu/

issues/2022/2/21/did-wages-keep-up-with-

ination-in-2021

Badger, E. & Bui., Q. (2019). Cities Start to

Question an American Ideal: A House with a

Yard on Every Lot. https://www.nytimes.com/

interactive/2019/06/18/upshot/cities-across-

america-question-single-family-zoning.html

Bailey, P. (2022). Addressing the aordable housing

crisis requires expanding rental assistance and adding

housing units. Center on Budget and Policy

Priorities. https://www.cbpp.org/research/housing/

addressing-the-aordable-housing-crisis-requires-

expanding-rental-assistance-and

Bartlett, R. P., Morse, A., Stanton, R., & Wallace, N.

(2019). Consumer-lending discrimination in the ntech

era. National Bureau of Economic Research. https://

www.nber.org/papers/w25943

Bateman, N. & Ross, M. (2021). e pandemic hurt