The Survival of American

Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929

CounCil on library and information resourCes

and the library of Congress

by David Pierce

September 2013

The Survival of

American Silent Feature

Films: 1912–1929

by David Pierce

September 2013

Council on Library and Information Resources

and The Library of Congress

Washington, D.C.

Commissioned for and

sponsored by the National

Film Preservation Board

Mr. Pierce has also created a da tabase of location

information on the archival lm holdings identied in

the course of his research.

See www.loc.gov/lm.

ISBN 978-1-932326-39-0

CLIR Publication No. 158

Copublished by:

and

Additional copies are available for $30 each. Orders may be placed through CLIR’s Web site.

This publication is also available online at no charge at http://www.clir.org/pubs/reports/pub158.

The paper in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard

for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials ANSI Z39.48-1984.

The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Pierce, David.

The survival of American silent feature lms, 1912-1929 / by David Pierce.

pages cm -- (CLIR publication ; no. 158)

“Commissioned for and sponsored by the National Film Preservation Board.”

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-1-932326-39-0 (alk. paper)

1. Motion picture lm--Preservation--United States. 2. Silent lms--United States--History and criticism. 3. Motion picture lm

collections--United States--Archival resources. I. Council on Library and Information Resources. II. Library of Congress. III.

National Film Preservation Board (U.S.) IV. Title.

TR886.3.P54 2013

791.43--dc23

2013026170

8

Cover: Cameraman Rudolph Bergquist (with Mitchell camera) and director Phil Rosen (kneeling) pose during the shooting of

The White Monkey (1925), an Arthur H. Sawyer-Barney Lubin production for First National Pictures, Inc. An incomplete copy of

this lm survives at the Packard Campus for Audio Visual Conservation, Library of Congress Motion Picture, Broadcasting and

Recorded Sound Division.

Photo: The Robert S. Birchard Collection.

Council on Library and Information Resources

1707 L Street NW, Suite 650

Washington, DC 20036

Web site at http://www.clir.org

The Library of Congress

101 Independence Avenue, SE

Washington, DC 20540

Web site at http://www.loc.gov

The National Film Preservation Board

The National Film Preservation Board was established at the Library of Congress by the National Film Preservation Act of 1988, and

most recently reauthorized by the U.S. Congress in 2008. Among the provisions of the law is a mandate to “undertake studies and

investigations of lm preservation activities as needed, including the ecacy of new technologies, and recommend solutions to im-

prove these practices.” More information about the National Film Preservation Board can be found at http://www.loc.gov/lm/.

iii

Contents

About the Author ......................................................v

Acknowledgments ....................................................vi

Foreword ............................................................vii

Executive Summary ....................................................1

Introduction ...........................................................5

The Silent Film Era Comes to an End......................................8

Overview of What Has Been Lost........................................10

Evolving Views of Silent Cinema ....................................10

The Cultural Loss..................................................11

The Cinematic Loss ................................................13

Methodology, Denitions, and Scope of This Study ........................16

Purpose of This Study ..............................................16

Denition of an American Silent Feature Film .........................17

Historical Period of Study ..........................................18

Sources of Data....................................................20

Findings .............................................................21

Most American Silent Feature Films Are Lost..........................21

Not All Surviving Films Are Complete ...............................25

Films Survive in Dierent Formats...................................26

The Preferred Edition is the 35mm Domestic-Release Version ........26

Many Films Survive Only in Small-Gauge Formats .................29

Summary of Surviving Film Elements ................................37

Source of the Surviving Copies ......................................39

Studios .......................................................41

Independent Producers . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 42

Stars and Directors .............................................46

Private Collectors ..............................................47

Films Surviving Only in Foreign Archives.............................48

Foreign Distribution............................................48

American Films Recovered from Foreign Archives..................50

Identication and Repatriation...................................52

The Likelihood of Future Discoveries .............................54

Additional Considerations .............................................55

Conclusions and Recommendations .....................................58

Appendix: FIAF Archives Reporting Holdings of

American Silent Feature Films.......................................62

Photo Credits .........................................................63

iv

Figures

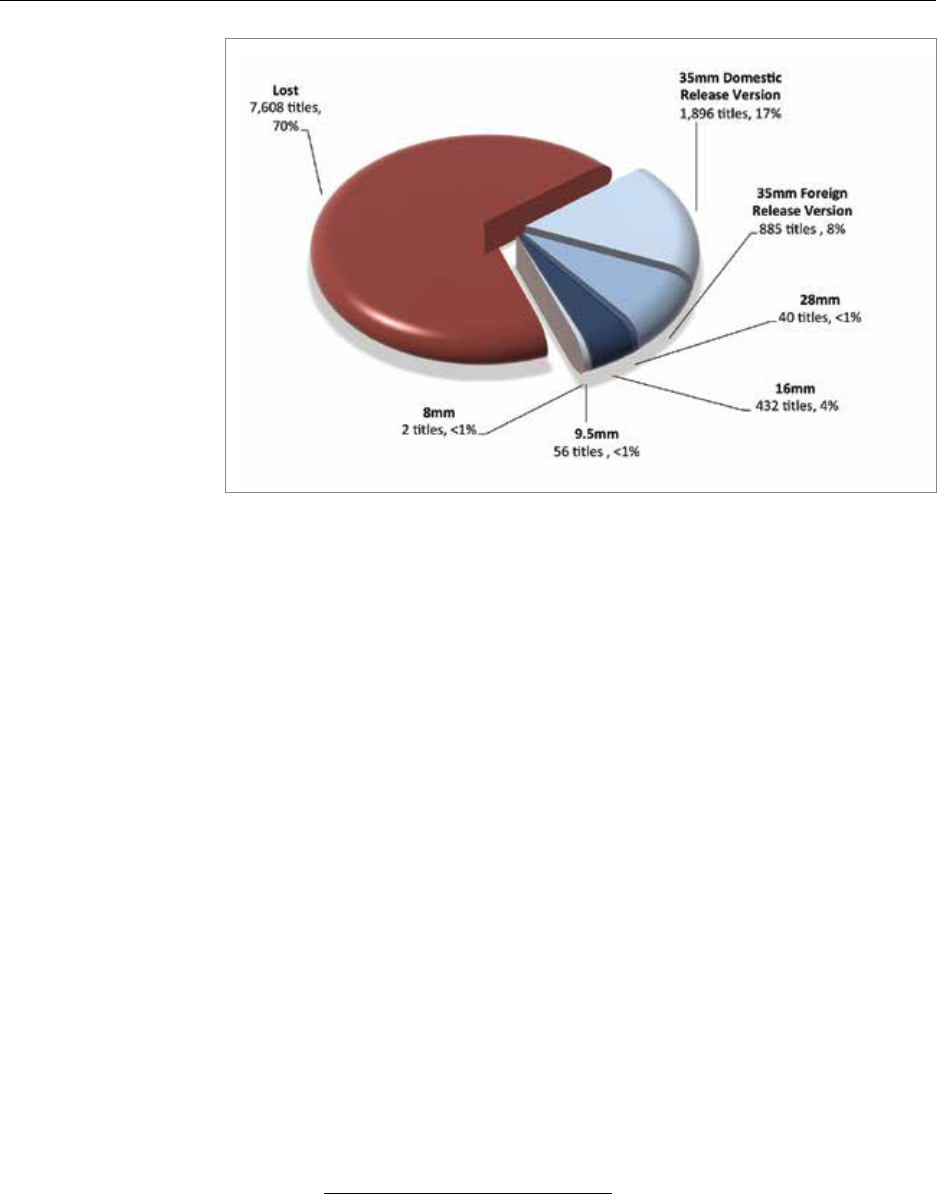

Figure 1: Survival Status of American Silent Feature Films,

by Year and Format ...........................................2

Figure 2: Through the Back Door (1921)–Poster .............................6

Figure 3: The Jazz Singer (1927)–Poster ...................................9

Figure 4: Ladies of the Mob (1928) Starring Clara Bow–Window Card ........10

Figure 5: Her Wild Oat (1927) with Drawing by H. B. Beckho–Poster .......12

Figure 6: The Mark of Zorro (1920)–Poster ................................14

Figure 7: War Brides (1916)–Advertisement ..............................15

Figure 8: The Four Horseman of the Apocalypse (1921)–Poster ................17

Figure 9: Number of U.S. Silent Feature Films Released, by Year............18

Figure 10: Three Bad Men (1926)–Lobby Card..............................20

Figure 11: The Patsy (1928)–Lobby Card ..................................23

Figure 12: Denitions and Categories of Film Completeness, with Examples ..24

Figure 13: American Silent Feature Film Survival,

by Categories of Completeness ................................26

Figure 14: Guide to Major Film Distribution Formats ......................28

Figure 15: Watching Small-Gauge Films at Home..........................29

Figure 16: Advertisement for Kodascope Libraries.........................30

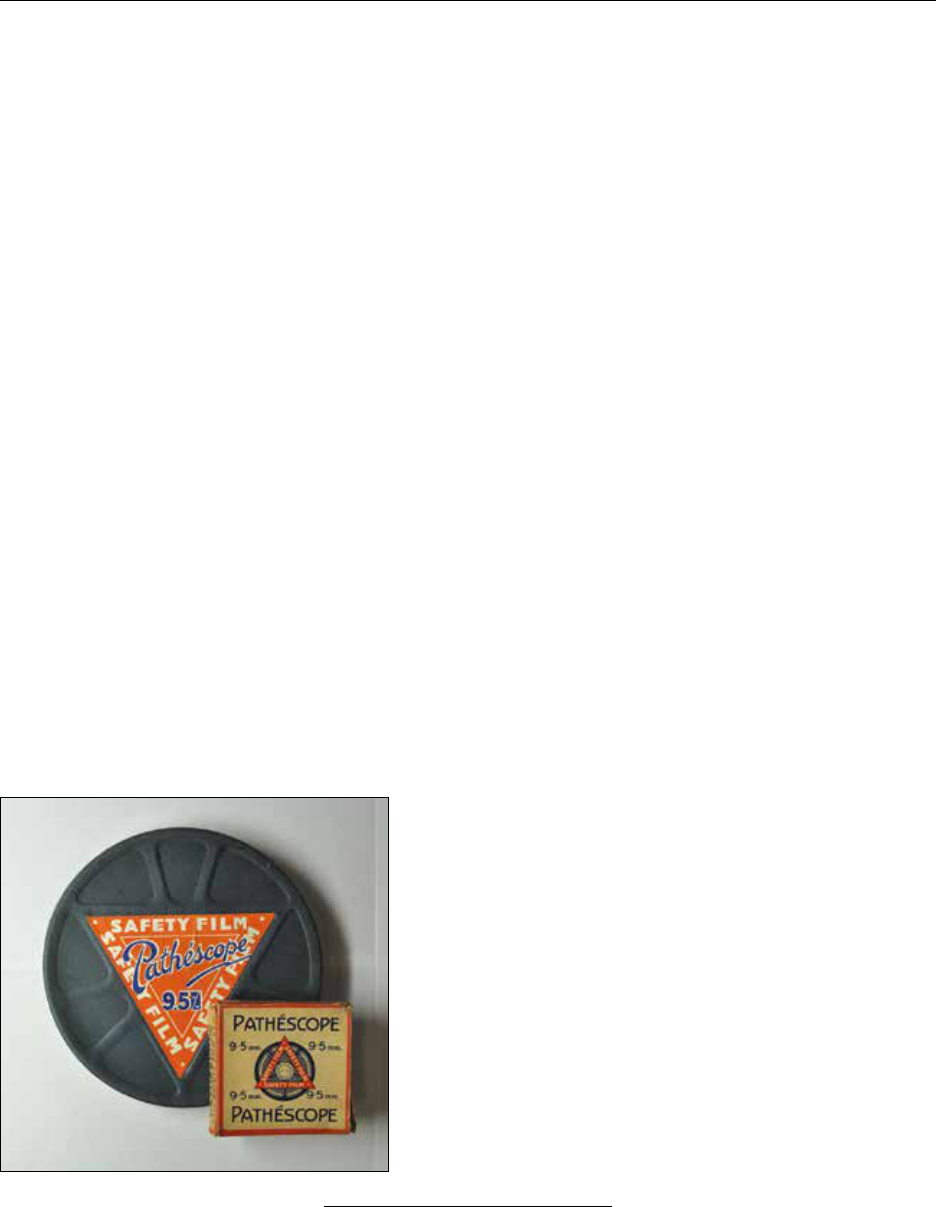

Figure 17: Pathéscope Reels ............................................34

Figure 18: American Silent Feature Film Survival, by Format

(complete and incomplete)....................................37

Figure 19: Statistics for Survival of American Silent Feature Films,

by Format and Completeness .................................38

Figure 20: Our Dancing Daughters (1928)–Lobby Card ......................40

Figure 21: Three Silent Paramount Features...............................44

Figure 22: The Red Kimono (1926)–Lobby Card.............................45

Figure 23: Location of Surviving American Silent Feature Films .............49

Figure 24: Tom Mix in Oh, You Tony! (1924)–Lobby Card....................52

Figure 25: Chicago (1928)–Lobby Card....................................54

Figure 26: King Vidor’s The Crowd (1928)–Poster ..........................56

Figure 27: John Barrymore in Beau Brummel (1924)–Poster ..................57

Figure 28: Surviving and Lost American Silent Feature Films, by Year ........61

Tables

Table 1: Sources of Surviving Copies of Studio-Owned American

Silent Feature Films, Grouped by Owner........................41

Case Studies

A Lost Classic Once Released in 16mm ...................................31

Directors and 16mm ...................................................32

Paramount Pictures....................................................43

v

About the Author

David Pierce is a historian and an archivist. At the British Film Institute (BFI)

from 2001 to 2004, he was head of preservation of the National Film and

Television Archive (NFTVA), and was appointed curator (head) of the archive

in 2002. He led the NFTVA’s restoration project for F. W. Murnau’s Sunrise

(1927) with the Academy Film Archive and Twentieth Century Fox.

Before his time at the BFI and since, Mr. Pierce has been active as a mo-

tion picture copyright consultant, advising motion picture producers, dis-

tributors, and exhibitors on the copyright and ownership of lms and televi-

sion programs. In 1999, he produced the theatrical, video, and DVD release of

Peter Pan (1924) through Kino International, recording a new orchestral score

and preparing new 35mm prints from a restored negative.

Mr. Pierce’s research examines the connections between lm history,

copyright, distribution, exhibition, and ownership, and his articles have

appeared in American Film, Film Comment, American Cinematographer, Film

History, and The Moving Image. His seminal article, “The Legion of the Con-

demned: Why American Silent Films Perished,” appeared in Film History in

1997 and was reprinted in This Film Is Dangerous, published in 2002 by the

International Federation of Film Archives (FIAF). His reference book on the

copyright status of lms of the 1950s was published in 1989.

Mr. Pierce founded the Media History Digital Library, a project to digitize

and provide free and open access to the printed record of the motion picture

and broadcasting industries. He has worked with archives, libraries, and col-

lectors to contribute to a comprehensive collection of research resources.

This is Mr. Pierce’s fourth research report for the American archival sec-

tor. His previous research reports on digital-access and commercial-access

strategies were commissioned by the Library of Congress, the UCLA Film &

Television Archive, and George Eastman House.

Mr. Pierce has also curated lm programs and lectured at the National

Film Theatre in London and the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC.

He is a member of the editorial board of the journal of the Association of

Moving Image Archivists, The Moving Image. He has lectured at lm-preserva-

tion schools, academic conferences, and festivals. He is a graduate of the Uni-

versity of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and received his MBA from George

Washington University in Washington, DC.

vi

Acknowledgments

This project was commissioned by the Library of Congress National Film

Preservation Board. I thank Alan Gevinson, Patrick Loughney, Stephen

Leggett, Gregory Lukow, Mike Mashon, Donna Ross, and Rob Stone for their

support and assistance.

An early version of the database associated with this report was devel-

oped over many years by Dr. Jon Mirsalis. His support of this project is ap-

preciated. Clyde Jeavons and Roger Smither provided the opportunity to

present an earlier version of this research at the 2000 International Federation

of Film Archives (FIAF) Congress in London.

Numerous archivists provided information for this project: Michael

Pogorzelski and Thelma Ross (Academy Film Archive); Paolo Cherchi Usai,

Ed Stratmann, Caroline Yeager, and James Layton (George Eastman House);

David Francis, Zoran Sinobad, James Cozart, Rosemary Hanes, Josie Walters-

Johnson, Madeline Matz, David Parker, Paul Spehr, and George Willeman

(Library of Congress); Ron Magliozzi, Katie Trainor, and Eileen Bowser

(Museum of Modern Art); Nancy Goldman (Pacic Film Archive); Jan-

Christopher Horak, Eddie Richmond, Robert Gitt, Todd Weiner, and Steven

Hill (University of California, Los Angeles); Elaine Burrows, Jane Hockings,

and Olwen Terris (British Film Institute/National Film and Television

Archive); Ronald Grant (Cinema Museum); Vladimir Opela (Národní

Filmovy Archiv); and archivists at the American Film Institute (Susan Dalton,

Larry Karr, Audrey Kupferberg, and Kim Tomadjoglou).

Input from studio archivists was invaluable: Bob O’Neil (NBC Universal);

Grover Crisp, Michael Friend, and Rita Belda (Sony Pictures Entertainment);

Schawn Belston (20th Century Fox Film Corporation), and Ned Price (Warner

Bros.).

I appreciate the support, past and present, of many archivists, schol-

ars, and collectors, including Gordon Berkow, Robert S. Birchard, Serge

Bromberg, Dan Bursik, Rusty Casselton, Herb Gra, Patricia King Hanson,

Eric Hoyt, Ed Hulse, Marty Kearns, Richard Koszarski, Ted Larson, Rob

McKay, Leonard Maltin, Bill O’Farrell, Richard Scheckman, Sam Sherman,

Anthony Slide, Jack Theakston, Karl Thiede, and Joe Yranski. For information

on 9.5mm, my thanks to contacts in Britain, including Patrick Moules and

Tony Sarey. My assessments of 9.5mm releases rely on the research of David

Wyatt and Garth Pedler. My appreciation to Scott MacQueen for sharing his

experience and insight.

I also thank the archivists who acquired many of the lms, worked for

their preservation, and made them accessible to the wider public. And special

acknowledgment to Kevin Brownlow, James Card, Paul Killiam, and David

Shepard.

vii

Foreword

On behalf of the Library of Congress, I am pleased to introduce this ground-

breaking study of the survival rates of feature-length movies produced in the

United States before the general advent of the sound era. Fellow historian

and archivist David Pierce has taken a major step toward resolving one of the

most intractable problems in the eld of lm preservation: determining, with

certainty, how many of the lms produced in the United States during the

twentieth century survive today. Mr. Pierce has also created a valuable da-

tabase of location information on the archival lm holdings identied in the

course of his research (see www.loc.gov/lm/).

Enormous eort and dedication over a long period of time was required

to collect and verify the information compiled in this report, involving travel

to the major lm archives of the world and careful research through many

types of archival and business records. Movies of the silent era posed a partic-

ularly dicult challenge because those lms have endured the longest period

of neglect and deterioration.

Film archivists and historians have long known that a large percentage

of the movies produced in the United States since the 1890s have been lost,

survive only in fragmentary form, or exist in copies of such inferior image

quality that it is almost impossible now to understand why they were often

hailed as works of great artistic achievement by the audiences who rst saw

them. A great deal of anecdotal information about lost lms has long been

available—particularly about the lms of the most famous lmmakers. But

this is the rst systematic survey of how many of the lms produced by U.S.

lm studios in the early twentieth century still exist and where the surviv-

ing lm elements are located in the world’s leading lm archives and private

collections.

When Congress enacted the National Film Preservation Act of 1988,

establishing the Library of Congress National Film Preservation Board and

National Film Registry, I directed that one of the long-term goals of the Board

would be to support archival research projects that would answer the open

questions about the survival rates of American movies produced, in all major

categories of production, during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. I

refer not just to the feature lms, but also to the travelogues, one- and two-

reel comedies, animated shorts, documentaries, newsreels, educational lms,

avant garde lms, and other types of movies that constituted the lm-going

experience throughout much of the twentieth century.

Mr. Pierce’s ndings tell us that only 14% of the feature lms produced

in the United States during the period 1912–1929 survive in the format in

which they were originally produced and distributed, i.e., as complete works

on 35mm lm. Another 11% survive in full-length foreign versions or on

viii

lm formats of lesser image quality such as 16mm and other smaller gauge

formats.

The Library of Congress can now authoritatively report that the loss of

American silent-era feature lms constitutes an alarming and irretrievable

loss to our nation’s cultural record. Even if we could preserve all the silent-

era lms known to exist today in the U.S. and in foreign lm archives—some-

thing not yet accomplished—it is certain that we and future generations have

already lost 75% of the creative record from the era that brought American

movies to the pinnacle of world cinematic achievement in the twentieth

century.

On a positive note, the inventory database compiled by Mr. Pierce not

only identies the silent-era archival lm elements that survive but also their

locations in the foreign lm archives that saved them from destruction. This

information will make it possible to develop a nationally coordinated plan to

repatriate those “lost” American movies and ensure that they are preserved

before further losses occur.

Mr. Pierce’s report is a model for the kind of fact-based archival research

that remains to be conducted on all genres of American lm beyond the scope

of silent-era feature lms. In addition, the same level of archival scrutiny

must be applied to all historically signicant audiovisual media produced

since the nineteenth century, including sound recordings, radio and television

broadcasts, and other new media judged to be worth saving and preserving

for posterity.

Thanks to the continued support of the Congress and the great generosity

of David Woodley Packard, the Library of Congress has the largest and most

up-to-date facility anywhere for preserving lm and audiovisual media to the

highest archival standards. In cooperation with colleagues in private sector

and non-prot archives, we will now be able to meet the challenge of preserv-

ing a more comprehensive archival record of American lm and audiovisual

creativity produced during the decades following the silent era.

—James H. Billington

The Librarian of Congress

1

The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929

Executive Summary

T

he era of the American silent feature lm lasted from 1912

until 1929. During that time, lmmakers established the

language of cinema, and the motion pictures they created

reached a height of artistic sophistication. These lms, with their rec-

ognizable stars and high production values, spread American culture

around the world. Silent feature lms disappeared from sight soon

after the coming of sound, and many vanished from existence.

This report focuses on those titles that have managed to survive

to the present day and represents the rst comprehensive survey

of the survival of American silent feature lms. The American Film

Institute Catalog of Feature Films documents 10,919 silent feature

lms of American origin released through 1930. Treasures from the

Film Archives, published by the International Federation of Film

Archives (FIAF), is the primary source of information regarding si-

lent lm survival in the archival community. The FIAF information

has been enhanced by information from corporations, libraries, and

private collectors.

We have good documentation on what American silent feature

lms were produced and released. This study quanties the “what,”

“where,” and “why” of their survival. The survey was designed to

answer ve questions:

How many lms survive?

There is no single number for existing American silent-era feature

lms, as the surviving copies vary in format and completeness. There

are 1,575 titles (14%) surviving as the complete domestic-release ver-

sion in 35mm. Another 1,174 (11%) are complete, but not the original

—they are either a foreign-release version in 35mm or in a 28 or 16mm

small-gauge print with less than 35mm image quality. Another 562

titles (5%) are incomplete—missing either a portion of the lm or an

abridged version. The remaining 70% are believed to be completely lost.

With respect to preservation, one studio stands out. Starting in

the early 1960s, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) preserved at the

corporation’s expense 113 silent features produced or distributed by

MGM or its predecessor companies. Starting in the 1930s, MGM also

gave prints or negatives for 120 silent feature lms to American ar-

chives, primarily George Eastman House. The survival rate of silent

lms produced by MGM after its founding in 1924 is 68%, the high-

est of any studio. For other companies, the proportion is much lower.

2

David Pierce

Who holds the surviving lms?

Foreign archives have proved to be an important resource for re-

covering important American lms and lling gaps in the careers

of directors and stars. The largest collection of exported American

lms has come from Národní Filmovy Archiv in the Czech Republic.

Even when lms survive in the United States, the foreign versions

often provide crucial missing material for restorations. Of the 3,311

American silent feature lms that survive in any form, 886 were

found overseas. Of these, 210 (23%) have already been repatriated to

an American archive either as part of a large-scale repatriation proj-

ect, such as the Goslmofond-Library of Congress agreement initi-

ated in 2010, or as a one-time trade.

How complete are the surviving lms?

Only 2,749 (25%) of American silent feature lms survive in com-

plete form. Another 562 (17% of the surviving titles and 5% of total

production) survive in incomplete form. Of these, at least 151 titles

survive in versions that have one reel missing. Another 275 titles

survive in versions that are not complete, missing two reels or more.

This includes the lms that survive only in 9.5mm abridgements and

many of the Eastman Kodak Kodascope 16mm home library releases

where footage was eliminated to reduce the running time. Finally,

there are 136 conrmed fragments, where one reel or less survives.

There are probably many more odd reels in collections, unidentied

and uncataloged.

Number of lms

Fig. 1: Survival Status of American

Silent Feature Films, by Year and

Format

3

The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929

In what format does the most complete copy survive?

Of the 2,749 silent features that survive in complete form, 406 exist

only in formats other than 35mm—small-gauge format 28mm and

16mm prints. Even more titles survive as abridged versions in 16 and

9.5mm copies. At least 72 American silent features were released in

28mm, mostly titles from the teens. Of these, 39 survive only in the

28mm format. Another 365 titles—11% of the 3,311 features that exist

in some form—survive only in 16mm editions.

In Europe, the home market was dominated by the Pathé 9.5mm

format. Of the 129 American silent features released in abridged

versions on 9.5mm, at least 56 exist in no other form. Another 18 fea-

tures survive only as paper prints submitted for copyright purposes

to the Library of Congress between 1912 and 1915.

Where was the best surviving copy found?

Of the 3,311 feature lms that survive in complete or incomplete

copies, roughly 1,699 were produced by one of the major studios

(or their predecessor companies). Of those, 531 titles passed directly

from the studio to an archive, or were preserved by the studio. Twice

as many studio titles, 1,168, have emerged from other sources.

Other lms survive because the original producer kept the nega-

tive or a print, directors and stars obtained copies for their personal

collections, or private collectors acquired a print.

It is impossible to determine in advance which lms will stand

the test of time as art, or which will prove signicant as a social re-

cord. With so many gaps in the historical record, every silent lm is

of some value and illuminates dierent elements of our history.

In the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s, when many more silent lms

still existed, there was never any hope to save everything; the focus

was to rescue the most important lms. The perennial lack of fund-

ing limited acquisitions and ensured that acquisition, cataloging,

and exhibition were on a small scale until the late 1960s, when the

National Endowment for the Arts began providing signicant nan-

cial support.

In addition, the public domain status of some independently

produced lms encouraged their survival. For the most part, their

producers were no longer in business and there was no one to le the

copyright renewal. Once they fell into the public domain, prints were

acquired by entrepreneurs who preserved them in the course of com-

mercial exploitation.

This report concludes with six recommendations:

1. Develop a nationally coordinated program to repatriate U.S.

feature lms from foreign archives. Of the 886 American silent

feature lms that survive only in foreign-release versions found

outside the United States, 676 (76%) have not been repatriated to

an American archive; the only copies are located overseas. These

titles should be reviewed and priorities set for repatriation to the

United States.

4

David Pierce

2. Collaborate with studios and rights-holders to acquire archival

master lm elements on unique titles. Many of the lms pre-

served by MGM in the 1960s still are not held by any American

archive, and other companies have some unique material. A

comparison of holdings between archives and studios will likely

identify additional titles held only by the rights-holders.

3. Encourage coordination among U.S. archives and collectors to

identify silent lms surviving only in small-gauge formats. This

project identied many lms held outside of FIAF archives in

nonarchival collections, including titles released on home library

gauges of 28mm, 16mm, and 9.5mm. A focused outreach program

would provide an opportunity to identify copies that still survive

in private hands.

4. Focus increased preservation attention on small-gauge lms.

The greatest cache of unexplored surviving titles are the 432

American silent feature lms that survive only in 16mm. Digital

scanning would allow high-quality preservation, with restoration

to follow, while the lm copies can be returned to their owners.

5. Work with other American and foreign lm archives to docu-

ment “unidentied” titles. An aggressive campaign to identify

unknown titles could recover important lms.

6. Encourage the exhibition and rediscovery of silent feature lms

among the general public and scholarly community. The num-

ber of America’s silent feature lms surviving in complete 35mm

copies as originally released is a disappointingly low 14% (1,575

of 10,919 features). This shortfall can be partially compensated by

an increased emphasis on providing wide public access to those

lms that do survive for scholarship and public enjoyment. While

the academic interest can be met by high-quality streaming video

over the Internet, these lms come to life only when they are

shown to audiences. Archives can shift from a primary focus on

preservation of their collections to lling the gaps in their hold-

ings through targeted acquisition, and then emphasizing wide

public availability of their holdings.

5

The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929

THAT THE UNITED STATES is fighting a losing battle to

save its film heritage is clearest from a sobering, often-noted

historical fact. Current efforts of preservationists begin from

the recognition that a great percentage of American film has

already been irretrievably lost—intentionally thrown away or

allowed to deteriorate.

Exactly how much of America’s film production has already

been lost remains difficult to say. The most familiar statistic,

which has attained its authority primarily through repetition, is

that we have lost 50% of all titles produced before 1950.

—Film Preservation 1993: A Study of the Current

State of American Film Preservation

1

Introduction

T

he era of the American silent feature lm lasted from 1912

to 1929, no longer than the period between the release of The

Godfather (1972) and The Godfather: Part III (1990). During that

brief span of time, lmmakers established the language of modern

cinema, while the motion pictures they created reached the height

of artistic sophistication. Going to the movies became the world’s

most successful form of popular entertainment, and these lms—

with their recognizable stars and high production values—spread

American culture around the globe.

The silent cinema was not a primitive style of lmmaking, wait-

ing for better technology to appear, but an alternate form of storytell-

ing, with artistic triumphs equivalent to or greater than those of the

sound lms that followed. Few art forms emerged as quickly, came

to an end as suddenly, or vanished more completely than the silent

lm. Once sound became the standard form of narrative lmmaking,

with the exception of some classics available for educational screen-

ings from the Museum of Modern Art, the masterpieces of the era

largely disappeared from view.

2

Nearly all sound lms from the nitrate era of the 1930s and

1940s survive because they had commercial value for television in

the 1950s and new copies were made while the negatives were still

intact. Unfortunately, silent lms had no such widespread com-

mercial value—then or now. Nearly 11,000 silent feature lms were

1

Film Preservation 1993: A Study of the Current State of American Film Preservation. Report

of the Librarian of Congress (Washington, DC: National Film Preservation Board of the

Library of Congress, 1993), 3. Available at http://www.loc.gov/lm/study.html.

2

The Museum of Modern Art Film Library was established in 1935 “for the purpose

of collecting and preserving outstanding motion pictures of all types and of making

them available to colleges and museums, thus to render possible for the rst time a

considered study of the lm as art.” “The Founding of the Film Library,” Bulletin of the

Museum of Modern Art 3, no. 2 (November 1935), 2.

6

David Pierce

produced, yet today, just 80 years after the silent lm era ended, only

a small proportion exists to be seen. The reasons for the loss—chemi-

cal decay, re, lack of commercial value, cost of storage—are docu-

mented elsewhere and are outside the scope of this report. Similarly

outside the purview of this report is the preservation status of the

lms that remain.

This report covers the survival of the American silent feature

lm, describing its cultural signicance and the statistics and impact

of its loss. This statistical analysis cannot reect the elements of en-

tertainment value and artistic achievement that are gone forever. All

the features of Buster Keaton, Charles Chaplin, and Harold Lloyd,

the lms Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks made during the

peak of their popularity in the 1920s, and the big epics, from The

Birth of a Nation (1915) to Wings (1927), still exist. But for every lm

that survives, there are half a dozen that do not, and for every clas-

sic that is seen today, many more of equal importance at the time are

now missing and presumed lost.

Many of Mary Pickford’s lms survive because she sent lms in

which she starred to the Library of Congress in 1946. “I wish to say

to you,” she wrote, “how happy I am that my pictures will be housed

in the Library of Congress and how greatly I appreciate

the honor conferred upon me by your wish to have them

there.”

3

Much of what survives is the result of the eorts of

U.S. and international lm archives curating their collec-

tions—identifying titles of interest and then actively seeking

copies, building relationships with rights-holders, and occa-

sionally acquiring entire collections.

More common than enthusiastic stars, however, were

unsentimental businessmen, such as producer Samuel

Goldwyn. In response to the Museum of Modern Art Film

Library’s inquiry about the destruction of sets on the backlot

he had taken over from Pickford and Fairbanks, Goldwyn

replied, “[You] must realize that I cannot rest on the laurels

of the past and cannot release traditions instead of current

pictures.”

4

The major studios were even less sentimental about their

traditions, with their focus only on current releases. The

exception was the active duplication program conducted by

MGM under the leadership of Raymond Klune and Roger

Mayer, which started around 1960. This led to the preserva-

tion of every lm still surviving in the studio’s vaults—lms

from MGM and aliated companies. Once preserved by the studio,

the remaining nitrate masters were donated to George Eastman

3

Mary Pickford to Luther Evans, Librarian of Congress, October 29, 1946. Motion

Picture Division Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

4

Samuel Goldwyn to John Abbott, Museum of Modern Art Film Library, telegram,

August 18, 1938. Goldwyn le, Master collection les, Museum of Modern Art

Department of Film. Thanks to Ron Magliozzi for making this material available.

Fig. 2: Through the Back Door

(1921)–Poster. Mary Pickford worked

to ensure the survival of her lms,

starting with a donation of lms in

which she starred to the Library of

Congress in 1946.

7

The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929

House starting in 1965. The other studios merely stored what nitrate

still remained in their collections, destroying copies as they started

to show evidence of deterioration.

Starting in 1968, the eorts of the American Film Institute (AFI),

funded by the National Endowment for the Arts, led to the place-

ment of other studio nitrate collections with archives. The surviving

Columbia Pictures and Warner Bros. silent negatives and Paramount

prints came to the Library of Congress, along with the few surviving

Universal silent features held by the studio. The Museum of Modern

Art acquired the Fox nitrate prints, with a few titles going to other

archives. Thirty years later, a discovery of additional Fox material

was placed with the Academy Film Archive. The First National

productions still in existence were deposited with George Eastman

House and the UCLA Film & Television Archive.

Each archive has also received lms from collectors, small com-

panies, and overseas archives, thus preserving and providing access

to titles that would otherwise have been lost or at least unavailable

in the United States. Dierences in collecting policies, personalities,

parent organizations, and funding challenges for the ve major U.S.

archives have led to a variety of holdings that together constitute the

national collection. Because some silent features are held by more

than one archive it is not possible to neatly characterize which ar-

chive has the most titles.

David Woodley Packard has provided the most wide-ranging

support for archival activities, rst through the David and Lucile

Packard Foundation and subsequently the Packard Humanities

Institute (PHI). The Packard Campus for Audio Visual Conservation,

designed and built by PHI for the Library of Congress, became op-

erational in 2008 with state-of-the-art storage facilities to ensure the

longevity of collections. The library’s nitrate-preservation program

began in 1958 and moved to an in-house preservation lm labora-

tory in 1970. This work is now performed at the custom-built ar-

chival lm laboratory at the Packard Campus. PHI also supported

the development of a nitrate-storage facility for the UCLA Film &

Television Archive in Santa Clarita, California, opening in 2008 as

the rst phase of a fully developed preservation center.

The transformation of lm archiving began in the 1980s, thanks

to the eorts of Sir J. Paul Getty, Jr., who provided nancial support

for a Conservation Centre and new nitrate vaults for the National

Film and Television Archive in the United Kingdom. In the United

States, additional signicant funding for archive infrastructure has

been contributed by Celeste Bartos, the Louis B. Mayer Foundation,

For every silent lm that survives

there are half a dozen that do not.

8

David Pierce

and the Academy Foundation.

5

This report focuses on those American silent feature lms that

have managed to survive to the present day. It is the rst comprehen-

sive survey of the survival of American silent feature lms. It pro-

vides context for both the survivors and the missing. The statistics

are humbling, documenting losses that would be unimaginable for

any other serious art form.

The report’s signicance lies not only in putting a gure to the

survival rate but also in establishing a statistical foundation for the

work to follow. Development of strategies to preserve and access the

remnants of America’s silent lm heritage can now be based on solid

data. The identication of gaps in holdings by American archives

can encourage the repatriation of titles that exist only in overseas

collections or with private companies. Even for titles that are already

preserved elsewhere, domestic archives perform an important role in

providing access.

For many titles, the copies released to home and school markets

are now the sole surviving record of those works. Because these edi-

tions are on safety lm, their acquisition and preservation had been

seen as less urgent, but the prints are subject to chemical deteriora-

tion. These small-gauge editions need focused attention in coopera-

tion with the collector community to ensure their survival, as unique

copies of lms become untraceable over time.

6

Developing accurate and comprehensive lists of surviving and

missing lms will support the archival sector’s goal to preserve

America’s cinema history and make it available to the public.

The Silent Film Era Comes to an End

The rst Academy Awards, cohosted by Academy President Douglas

Fairbanks and Vice President William C. deMille, were presented at a

dinner at the Hollywood Roosevelt Hotel on May 16, 1929. While the

Oscars represented a new maturity for the industry, the rst awards

were also a farewell to its early years. Since the most commercially

successful lm of the season was not successful in the voting, the

Academy board created a special award for The Jazz Singer. “These

awards are given for work accomplished during the year 1928,”

deMille told the audience. “There is only one award in this whole list

that has anything to do with talking pictures. It seems strange when

you stop and look over the eld and see how many talking pictures

are being distributed today.”

7

5

The Celeste Bartos Film Preservation Center of the Museum of Modern Art opened

in 1996, the same year as George Eastman House’s Louis B. Mayer Conservation

Center. The Pickford Center for Motion Picture Study in Hollywood, home of the

Academy Film Archive, opened in 2002. The Academy Foundation, the educational

and cultural arm of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, funds the

Academy Film Archive.

6

For example, a 16mm original print of Wild Beauty (1927), a Universal western with

Rex the Wonder Horse, not held by any archive, sold on eBay on May 13, 2011.

7

AMPAS Bulletin, no. 22, (June 3, 1929): 2–3, The Academy of Motion Picture Arts

and Sciences, Margaret Herrick Library Digital Collections. Available at http://

digitalcollections.oscars.org.

9

The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929

The Academy had selected the lms that its

members saw as the pinnacle of their art, a seamless

combination of expressive acting, expressionistic

photography, the moving camera, a minimum of

dialog and titles, and an unreality of time and place.

This technique was being replaced by a new type of

lm that, at least initially, often featured stage acting,

static photography, a xed camera, and an emphasis

on dialogue, sound, and space that audiences found

refreshing and real. Those “talking lms” managed

to overtake and obliterate the silent feature so rapidly

that by the date of the rst Academy Awards, nearly

every rst-run lm playing in New York City was a

talkie. A month later, Douglas Fairbanks started work

on his rst all-talking lm. The holdouts had surren-

dered and the sound revolution was complete.

8

Silent lms became an increasingly distant

memory as the history of the rst four decades of lm

was left behind. In 1947, to commemorate its twenti-

eth anniversary, the Academy scheduled screenings

of each year’s award-winning lms. After a mere

two decades, ve of the winners from the rst year

could not be shown, as “no prints are available.”

9

Within another two decades, several titles that were

screened in the 1947 series no longer were believed

to exist, including two lms starring German actor

Emil Jannings: The Way of All Flesh (1927), featuring his Academy

Award–winning performance, as well as Ernst Lubitsch’s The Patriot

(1928), the only Best Picture nominee that today is not known to ex-

ist (beyond a beautifully executed fragment).

10

The New York Times

called the latter “a gripping piece of work” and praised Jannings’

performance in “the most dicult role of his lm career.”

11

Unfortunately, we have to accept the reviewer’s word for it, as

we cannot judge for ourselves.

8

On May 16, 1929, the seven rst-run Times Square theaters that changed programs

weekly were running six talkies and one silent. The 12 extended-run theaters were

running 10 talkies and 2 part-talkies. The rst Oscars were presented for lms released

between August 1, 1927 and July 31, 1928, following the theatrical season. Academy

Awards Database, 1927/1928. Available at http://awardsdatabase.oscars.org/ampas_

awards. Starting in 1934, the awards were presented for lms released in the previous

calendar year.

9

The unavailable titles were The Last Command, with Emil Jannings; Sunrise; The

Dove, with Norma Talmadge; Tempest, with John Barrymore; and Charlie Chaplin’s

The Circus. All these lms survive today, though the safety-lm copy of The Dove has

extensive nitrate decomposition copied from the deteriorating original.

10

The Way of All Flesh was shown at the Academy Theatre on November 23, 1947. A

three-minute excerpt from The Way of All Flesh was included in the Paramount short

Movie Milestones no. 1 (1935). A seven-minute fragment from The Patriot is held by

the Cinemateca Portuguesa - Museu do Cinema. The trailer for The Patriot has been

preserved by the UCLA Film & Television Archive. The trailer is included in the DVD

set, More Treasures from American Film Archives, 1894–1931.

11

Mordaunt Hall, “The Patriot,” New York Times, August 18, 1928. Available at http://

movies.nytimes.com/movie/review?res=990CE0D61431E33ABC4052DFBE668383639

EDE.

Fig. 3: The Jazz Singer (1927)–Poster.

When the rst Academy Awards

were presented in 1929, silent lm

was already on the decline. A special

award was created for The Jazz

Singer, the rst feature-length motion

picture with synchronized dialog

sequences.

10

David Pierce

Overview of What Has Been Lost

Evolving Views of Silent Cinema

Clara Bow was the living embodiment of the Roaring

Twenties and remains as luminous a personality today as

when she was one of the ve top box oce draws in the late

1920s. Her vitality, enthusiasm, and sensuality are undimin-

ished, and the movies from the peak of her career—the half

of her lms that survive today, that is—still delight audi-

ences. Perhaps this is not as signicant a loss to humanity

as the disappearance of all but 19 of the more than 90 plays

by Euripides, but at least we can attribute the absence of the

latter to the loss of the Ancient Library of Alexandria, not to

neglect.

12

For popular artists such as Clara Bow and her con-

temporaries, the view of both the industry and the public

regarding their work was captured in 1934 by Los Angeles

Times drama critic Edwin Schallert:

Making pictures is not like writing literature or composing

music or painting masterpieces. The screen story is essentially

a thing of today and once it has had its run, that day is nished.

So far there has never been a classic lm in the sense that there is

a classic novel or poem or canvas or sonata. Last year’s picture,

however strong its appeal at the time, is a book that has gone out

of circulation.

13

Starting in the late 1940s, television led to renewed life and au-

diences for sound lms. Meanwhile, silent lms succumbed to the

perils of nitrate lm (re or decay), lack of commercial value, and an

extended period of disinterest by both owners and audiences.

14

But tastes change, views of what is important evolve, and the

passage of 80 years has seen an acceptance of lm as one of the ma-

jor new art forms of the twentieth century. With the National Film

Preservation Act of 1988, the U.S. Congress established the National

Film Registry in the Library of Congress to designate lms that are

“culturally, historically, or aesthetically signicant.” Librarian of

Congress James H. Billington has selected 67 silent feature lms for

the registry (out of 600 total), and hundreds of other lms of the era

have been nominated by the general public.

15

12

David Stenn, Clara Bow: Runnin’ Wild (New York: Doubleday, 1998), 157–162. Martha

Nussbaum, Introduction to The Bacchae of Euripides: A New Version (New York: Farrar,

Straus and Giroux, 1990), xxvii.

13

Edwin Schallert, “Film Producers Shaken by Clean-Up Campaign,” Los Angeles

Times, June 10, 1934, 10.

14

For a detailed analysis of why most silent lms are lost, see David Pierce, “The

Legion of the Condemned: Why American Silent Films Perished,” Film History 9,

no. 1, (1997): 5–22. Reprinted with additional information in This Film Is Dangerous:

A Celebration of Nitrate Film, eds. Roger Smither and Catherine Surowiec (Brussels:

Fédération International des Archives du Film, 2002), 144–162.

15

Public Law 100-446: National Film Preservation Act of 1988. See http://www.loc.

gov/lm/lmabou.html, and Eric Schwartz, “The National Film Preservation Act

of 1988: A Copyright Case Study in the Legislative Process,” Journal of the Copyright

Society of the U.S.A. 36 (January 1989): 137–159.

Fig. 4: Ladies of the Mob (1928)

starring Clara Bow–Window Card.

None of the four feature lms that

starred Clara Bow in 1928 are known

to exist.

11

The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929

Two of Clara Bow’s 1927 lms—It and Wings—are on the registry.

They are among the hundreds of silent lms shown in public screen-

ings each year. The San Francisco Silent Film Festival, which has

showcased both titles, annually attracts audiences of 13,000 people

over four days. But there will be no nominations or festival show-

ings for the lm that, as Frank Thompson noted, “was an important

opportunity [for Bow] to take on a starkly dramatic role after a long

string of what seemed to her inconsequential comedies and racy dra-

mas.” Ladies of the Mob is permanently out of circulation, along with

the other three features Clara Bow made in 1928—lost as assuredly as

is Euripides’ The Cretans.

16

The Cultural Loss

That this report focuses on cold statistics, numbers, and percent-

ages should not blind us to the cultural and historical loss that is

the greatest impact of the lost lms. Motion pictures in the teens

and twenties—before network radio, television, cell phones, and the

Internet—had an inuence that is hard to imagine today. In the mid-

1920s, movie theater attendance in the United States averaged 46

million admissions per week from a population of 116 million, ve

times the per capita attendance rate today.

17

“Because of the immensely seductive atmospherics of the overall

experience,” Scott Eyman wrote, “the silent lm had an unparal-

leled capacity to draw an audience inside it, probably because it

demanded the audience use its imagination. Viewers had to supply

the voices and sound eects; in so doing they made the nal creative

contribution to the lmmaking process. Silent lm was about more

than a movie; it was about an experience.”

18

Sharing that emotional visual experience in a darkened theater

with hundreds or even thousands of fellow lm goers with appropri-

ate music was a key part of the appeal. “The silent cinema was not

just a roll of lm in a can,” wrote Richard Koszarski. “It was a com-

plex social, aesthetic and economic fabric that brought the power of

16

Frank Thompson, Lost Films: Important Movies That Disappeared (New York: Citadel

Press, 1996), 234.

17

Historical attendance gures from Film Daily Yearbook of Motion Pictures (New

York: The Film Daily, 1951), 90. Modern attendance gures from “Theatrical Market

Statistics 2012,” Motion Picture Association of America, 6. Available at http://mpaa.

org/policy/industry.

18

Scott Eyman, The Speed of Sound: Hollywood and the Talkie Revolution 1926–1930 (New

York: Simon & Schuster, 1997), 20.

Motion pictures in the teens and twenties —before

network radio, television, cell phones, and the Internet—

had an inuence that is hard to imagine today.

12

David Pierce

the moving image into the twentieth century.”

19

Local theaters across

the nation were instrumental in helping bring together their com-

munities, while the lms they exhibited captured and reected the

environment in which they were made. Surviving lms permit us to

see city streets where horses still outnumber the cars that were soon

to displace them, and the hamlets and villages where the majority of

Americans still lived. Idealized innocence and grim reality coexist

in these works, along with documentary evidence of what people

wore, drove, and used to outt their houses. We can watch

the early years of ight, evolving attitudes toward minorities

and women, and rapid changes in public morals, the casual

use of cigarettes, and trolley cars.

Often these insights come in the smaller lms, especially

those dramas set in rural America where characters face

the moral dilemmas that result from rapid cultural change.

“Little programmers of the twenties may have relatively little

to oer artistically, but they are a marvelous record of their

times,” William K. Everson noted. “Our Dancing Daughters

is often referred to as the ‘denitive’ Jazz-Age lm, but it’s

the Jazz Age by luxurious MGM standards. Universal’s The

Mad Whirl and lower down the scale, Pathé’s Walking Back,

actually tell us more about how the jazz-age aected the av-

erage person, while Walking Back in addition comments on

the impact that Ernest Hemingway’s writing was having, by

shamelessly plagiarizing it!”

20

With such a hold on the popular imagination, motion

pictures inuenced fashion and leisure, and drove the emer-

gence of modern celebrity culture. As one example, actress

Colleen Moore presented a feisty yet wholesome innocence,

and her natural humor gave weight to her comedies and

depth of character to her dramatic roles. Moore received

more than 10,000 fan letters a week in 1926, when she was

the top female star and earning $10,000 per week. Moore’s

breakthrough was the starring role in Flaming Youth (1923),

where she personied a new breed of woman, the apper.

Audiences could visualize “just what a young woman who

amed and apped really looked like,” Jeanine Basinger

noted. “What she looked like was Colleen Moore.” Magazine art-

ist John Held, Jr., adopted Moore’s image of the chirpy and slightly

muddle-headed girl for his popular cartoons of bird-brained ap-

pers and their college boyfriends. Moore’s short hair led the national

craze among young women for “bobbed” hairstyles, and she further

inuenced fashion trends with the glamorous costumes and casual

outts she wore in her lms.

21

19

Richard Koszarski, An Evening’s Entertainment: The Age of the Silent Feature Picture,

1915–1928 (New York: Scribner, 1990), 324.

20

William K. Everson, “Should Everything Be Saved?,” Films in Review 29, no. 9

(November 1978): 541–544, 563.

21

Jeanine Basinger, Silent Stars (New York: Knopf, 2000), 420. The earliest lm in the

genre was The Flapper (1920), with Olive Thomas.

Fig. 5: Her Wild Oat (1927) with

Drawing by H. B. Beckhoff–Poster.

The lms of Colleen Moore and her

apper persona helped dene the

1920s.

13

The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929

The Cinematic Loss

The best-known silent lm actress today may be a ctional one,

Norma Desmond, the half-mad silent lm diva portrayed by a

genuine silent lm diva in Billy Wilder’s Sunset Blvd. (1950). Gloria

Swanson gives a riveting portrayal of a long-forgotten movie god-

dess for whom time stands still, eternally mired in the Hollywood

of 1928, subsisting on memories. As the lm’s doomed narrator tells

us, Norma is “still waving proudly to a parade which had long since

passed her by.” She’s a handy, if mostly inaccurate, stand-in not for

the dozens of real-life actresses who had short but generally satisfy-

ing careers and went on with their lives, but for the few stars, such as

Swanson, who held on to leading roles with an iron will and a tire-

less work ethic.

22

Norma shutters herself in her Beverly Hills mansion, with private

screenings of Queen Kelly, the genuine but never completed Swanson

lm of 1928. Norma can screen Queen Kelly, and so can we to this day,

because Miss Swanson placed her 35mm nitrate copy, along with a

few other lms from her career, at George Eastman House. But no ac-

curate assessment of the careers of the ctional Miss Desmond’s real-

life contemporaries is possible. There is so little to see.

The lms that survive provide the breadth of silent lm cul-

ture—it is still possible to view the full range of productions—but we

are missing the depth, as what survives are representative examples.

Scholars cannot adequately document the art and science of lm-

making without primary sources—the lms themselves—thus mak-

ing it challenging, if not impossible, to write in depth about many of

the people and companies that produced these lms.

Mary Pickford owned many of her lms and paid for their pres-

ervation. Of her 48 features, 8 lms from the rst three years of her

career are lost, but the rest survive. This is a very good survival rate

compared with that of many of her peers.

Pola Negri became a star in Germany, and the American period

of her silent lm career, from 1923 to 1928, continued her worldwide

fame. Although Paramount’s best directors guided her, the American

lms seldom matched the quality of her early lms in Germany.

Only 6 of her 20 starring American lms survive—the Museum of

Modern Art bought a print of Mauritz Stiller’s Hotel Imperial (1927)

from Paramount, as did George Eastman House with Barbed Wire

(1927). A Woman of the World (1925) exists in its complete American-

release version, and three others in their foreign versions. There is no

22

Billy Wilder, Sunset Boulevard (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999), 44.

Scholars cannot adequately document

the art and science of lmmaking without

primary sources.

14

David Pierce

trace of the 14 other titles.

23

Of the 39 features that screen “vampire” Theda Bara

made between 1914 and 1919, only 2 survive. Norma

Talmadge was a star of “women’s pictures” from 1916

through to the transition to sound, yet only 28 of her 48 star-

ring features survive in complete form. Only 2 of the 34 lms

dramatic actress Pauline Frederick made before her career

triumph in Madame X (1920) are known to exist. And the

story is little better for Swanson herself, with only 15 of her

38 features surviving in complete 35mm editions.

24

We are fortunate to have all the Douglas Fairbanks lms

of the 1920s that established the popular images of Robin

Hood, Zorro, The Three Musketeers, and pirate adventures.

Whether you’ve seen the lms or not, it is Fairbanks’ rep-

resentations of these characters that live today, ltered and

morphed over the years by Errol Flynn, Antonio Banderas,

Michael York, and Johnny Depp. But we cannot follow the

career of Tom Mix, who transformed the western from its

Victorian theatrical melodrama roots into contemporary ac-

tion narrative. Only 12 of Mix’s 85 lighthearted westerns for

Fox survive in their original-release versions.

If popular culture is reected through entertainment,

then where are the major blockbusters of their day? There are no

known copies of The Rough Riders (1927), Victor Fleming’s tribute to

Theodore Roosevelt in the Spanish-American War. Who has seen the

surprise hit of 1924, the independently produced The Dramatic Life of

Abraham Lincoln, which codied the Lincoln myth for years to come?

Aquatic ballerina Annette Kellerman was a personality of such mag-

nitude that her life story was lmed in Technicolor as Million Dollar

Mermaid in 1952, but today we have no trace of A Daughter of the Gods

(1916), her “million dollar movie” lmed on location in Jamaica.

Despite three reissues and Kellerman’s appearance in a “tasteful”

and widely discussed nude scene (both conditions that might have

encouraged the lm’s survival), the lm has vanished.

Cinematic adaptations would tell us much about the impact

of popular plays and novels. Among the missing are Main Street

(1923) and Babbitt (1924), based on the bestsellers by Sinclair Lewis,

America’s rst author to win the Nobel Prize in literature; and

The Beautiful and Damned (1922) and The Great Gatsby (1926), con-

temporary, on-the-spot adaptations of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s novels.

Adaptations from the stage fare no better. Brewster’s Millions is a

23

In 2011, the EYE Film Instituut Nederland restored Herbert Brenon’s The Spanish

Dancer (1923) from a nitrate print with Dutch titles, a nitrate print with Russian titles

from the Cinémathèque Royale de Belgique, and two 16mm copies of the Kodascope

abridgement. Fitzmaurice’s Bella Donna (1923) and Ernst Lubitsch’s Forbidden Paradise

(1924) exist in their foreign-release versions. There is also a reel of outtakes from The

Woman on Trial (1928) at the Museum of Modern Art.

24

For details on the survival of the lms of Mary Pickford, see Christel Schmidt,

“Preserving Pickford: The Mary Pickford Collection and the Library of Congress,”

The Moving Image 3, no. 1 (Spring 2003): 59–81. Available at http://muse.jhu.edu/

demo/the_moving_image/v003/3.1schmidt.pdf. For background information on the

other female stars, see Greta de Groat’s Unsung Divas of the Silent Screen website for

biographies and lmographies (http://www.stanford.edu/~gdegroat).

Fig. 6: The Mark of Zorro (1920)–

Poster. Douglas Fairbanks

established the popular images of

characters, including Zorrro, that

endure today.

15

The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929

comedy of inheritance from a 1906 play that has been lmed eight

times since 1914, most recently in 1985. Clearly the story resonates

across the century from our great-grandparents’ time to today, but

three silent versions of Brewster’s Millions—a 1914 version with

Edward Abeles, who created the role on stage; a 1921 version with

Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle; and a 1926 version with Bebe Daniels—are

as lost to history as their live theatrical counterpart.

Humorist and commentator Will Rogers was one of the most

well-known and beloved American public gures of the 1920s. He

starred in 16 silent features, of which only 5 survive.

25

Other popu-

lar comedians are even less well represented. One such is Raymond

Grith. Critic Walter Kerr tried to reestablish Grith’s reputation in

the 1970s in his book The Silent Clowns. Kerr judged Grith to be just

as funny, just as talented, and just as important as Charles Chaplin,

Buster Keaton, and Harold Lloyd. Nearly every one of their lms

survived to be seen by later generations. Kerr noted that “one reason

for the neglect of Grith’s lms today is that so little of his output is

available. Of the 9 or 10 starring lms he made between 1925 and the

end of the silent period, only 3 can be seen at the moment; a fourth—

even perhaps a fth—is known to exist but is not yet in museum

circulation. It is dicult to develop a new audience for a man

who is more than half invisible.”

26

History is told by the win-

ners, and for lm history, survival alone can be sucient to

enter the pantheon.

And how much better would we understand media

manipulation if we could see the World War I–preparedness

drama The Battle Cry of Peace (1915), showing an invasion of

the United States by an unnamed (but Teutonic) attacker;

or its complement, the pacist War Brides (1916), in which

widowed mothers protest the war. Moving Picture World ac-

claimed the lm for reaching “a tragic height never before

attained by a moving picture” with a climax “which is prob-

ably the most powerful ever seen on the screen.” How clearly

could be demonstrated the mercurial change in public dis-

course once the United States joined the war, as these lms

were replaced by such unsubtle propaganda lms as The

Kaiser, Beast of Berlin (1918). Extant advertising, still photos,

and reviews can go only so far to communicate their eect. If

we cannot view these lms, we cannot accurately judge their

purpose, their appeal, and their import.

27

For many other titles, sometimes only a tantalizing frag-

ment exists. Only a single reel survives of the only missing

Greta Garbo feature, The Divine Woman (1928). Six of the lms by

director Lois Weber are missing more than half their reels. Even

when a lm does survive with its content intact, its experience can

be substandard because of poor quality or worn elements. The visual

25

Will Rogers also starred in a now-lost British production Tiptoes (1927), opposite

Dorothy Gish.

26

Walter Kerr, The Silent Clowns (New York: Knopf, 1975), 298.

27

Edward Weitzel, “War Brides,” The Moving Picture World (December 2, 1916):

1343–1344.

Fig. 7: War Brides (1916)–

Advertisement from Moving Picture

World, 5 Nov. 1916, p. 1099. Only

reviews and advertisements survive

for this World War I-era lm.

16

David Pierce

beauty of Tod Browning’s West of Zanzibar (1928), with Lon Chaney,

and John S. Robertson’s The Single Standard (1929), with Greta Garbo,

are compromised because they were copied from heavily worn

prints. Beggars of Life (1928), with Wallace Beery and Louise Brooks,

survives only in a single original 16mm copy. Beautifully staged and

photographed lms like Herbert Brenon’s A Kiss for Cinderella (1925),

Roland West’s The Dove (1928), and Raoul Walsh’s The Monkey Talks

(1927) each have one entire, critical reel copied not quite in time that

exists as an oily, splotchy, ickery muddle of decaying and barely

legible images.

Meanwhile, innumerable low-budget westerns and program

pictures exist in immaculate original prints barely used since their

original release.

Methodology, Denitions, and Scope of This Study

Purpose of This Study

Good documentation exists on which American silent feature lms

were produced and released. This study quanties the “what,”

“where,” and “why” of their survival. This report does not examine

which lms have been preserved or restored, or are commercially

available. The focus is strictly on what survives.

This survey was designed to quantify what still exists, whether

the materials originated with an owner or elsewhere, and where the

surviving copies are located—in an archive, a commercial collection,

a nonarchive library, or a private collection. In some cases, based on

distribution catalogs, this study considers the likelihood that copies

exist with the private-collector community. Underlying the study are

some key facts:

• American lms were distributed worldwide; copies may be found

anywhere.

• Image quality is vitally important for silent lms; the original

production format of 35mm for theatrical releases is the preferred

format.

• Many lms survive in alternate editions: abridgements, reis-

sues (with reedited footage, rewritten titles, or added narration),

foreign-release versions (with alternate footage or rewritten titles).

These variants should be documented where possible.

• Hundreds of lms were released for nontheatrical showing in

small-gauge formats such as 16mm. Many of these lms are

known to survive only in prints held by private collectors; it is

certain that others survive as well.

The survey was designed to answer ve questions:

1. How many silent feature lms survive?

2. Who holds the surviving lms?

3. How complete are the surviving lms?

4. In what format does the most complete copy survive?

5. Where was the best surviving copy found?

17

The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929

The data from the survey were then analyzed to develop

statistics that determine:

• the percentage of silent features that survive, by format and

completeness;

• correlation of survival to year of release;

• comparisons of survival rates for lms by major studios and by

major stars and directors; and

• the sources of best surviving copies: the important role of rights-

holders in preservation.

Denition of an American Silent Feature Film

After the nickelodeon era, the industry began moving to longer

lms, and some titles, notably The Life of Moses (1909), were rst re-

leased as a series of shorts, with each individual reel the highlight

or “feature” of that day’s program. Later, the reels were combined

and the result was distributed as a stand-alone feature. As a pro-

ducer noted in 1917, “In the majority of cases every lm of more than

three thousand feet in length has recently been termed a feature” as

the term “has been applied largely to the length regardless of

merit.”

28

Program features in the teens were usually ve reels, and by

the 1920s seven reels was more common. Big-budget lms ran

longer to justify their higher rentals. Director Rex Ingram was

one of the few Universal sta directors in the teens who could

deliver on the promise of sensitive titles such as The Chalice of

Sorrow (1916) and The Reward of the Faithless (1917) within the

limitation of a ve-reel running time. A decade later, Ingram’s

production of The Magician (1926), the silent lm that most pre-

gures the monster-horror lms of the early sound period, was

a regular program release at seven reels. Ingram’s epic The Four

Horsemen of the Apocalypse (1921), which captured the impact of

World War I on the generation that lived through it and catapult-

ed Rudolph Valentino to stardom, was 11 reels.

This report relies on the denition of a feature lm devel-

oped by the editors of the American Film Institute Catalog of

Feature Films: “lms of four reels or more, produced in the

United States.”

29

Toward the end of the 1920s, the denition of a silent feature

becomes more problematic. Films were released with synchro-

nized scores of music and eects, and then with talking sequences.

Films were prepared in two versions for American release: silent

28

George K. Spoor, “Standardizing the Abused Word ‘Feature’,” Motion Picture News,

January 20, 1917, 382. Also see W. Stephen Bush, “The Future of the Single Reel,” The

Moving Picture World (April 19, 1913): 256.

29

Patricia King Hanson, ed., The American Film Institute Catalog of Motion Pictures

Produced in the United States. F1. Feature Films, 1911–1920 (Berkeley: University of

California Press, 1988), xv. Despite the title, the catalog includes no features from 1911.

Fig. 8: The Four Horsemen of the

Apocalypse (1921)–Poster. With an 11-

reel running time, the production was

among the longest silent feature lms.

18

David Pierce

(for theaters that had not yet installed sound equipment) and sound

(either all-talking or part-talking with music and sound eects). A

separate, nondialog edition was prepared for foreign markets, either

mute or with a soundtrack of music and eects. This study includes

lms with recorded scores, talking sequences, or both. Titles released

in both all-talking and silent versions are excluded.

30

Historical Period of Study

The list of silent feature lms referenced in this study is derived

from the AFI Catalog of Feature Films, which documents 10,919 fea-

ture lms of American origin released between 1912 and 1930.

31

The

range of years and the number of lms released per year are shown

in Figure 9.

The era of the teens is arguably the period of American cinema

with the most diversity of creative technique and certainly the period

in which the aesthetics of lmmaking underwent major evolution. It

is the period in which the feature lm was born, matured, and ow-

ered. The absence of the majority of the works from these years has

30

The part-talking The Jazz Singer and Lonesome meet the qualications. Not included

are Welcome Danger (1929), with Harold Lloyd; William Wyler’s Hell’s Heroes (1930);

and Coquette (1929), with Mary Pickford—even though these lms exist in two distinct

editions, as all-talking lms and as silent lms. To include these titles would skew the

statistics by also adding hundreds of silent versions of all-talking lms released in

1929, 1930, and 1931. Few of the silent versions of these later lms survive, and most,

such as the silent edition of Dracula (1931), were mute versions of the talkie, with

title cards inserted to cover the spoken dialogue, rather than separately staged and

photographed silent lms.

31

The twenties are covered in Kenneth W. Munden, ed., The American Film Institute

Catalog of Motion Pictures Produced in the United States. F2. Feature lms, 1921–1930

(New York: R.R. Bowker, 1971). The combined catalogs are available at http://www.

a.com/members/catalog. The listing concludes with 1930, the year of the nal

major studio silent releases. This excludes at least eight lms from the 1930s released

with music scores but no narration. These were mostly travelogues, with the notable

exceptions of Charlie Chaplin’s City Lights (1931) and Modern Times (1936).

Fig. 9: Number of U.S. Silent Feature

Films Released, by Year

19

The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929

skewed our historical perspective. We know well the contributions of

men like D. W. Grith, Cecil B. DeMille, and Thomas H. Ince. Less

well acknowledged, if at all, are the earliest features by women lm-

makers. Three examples, all of which survive, are Cleopatra (1912),

produced by actress Helen Gardner; Eighty Million Women Want?

(1913), a political drama with a cameo appearance by British surag-

ette Emmeline Pankhurst; and From the Manger to the Cross (1913),

lmed on location in the Middle East with a scenario by actress and

screenwriter Gene Gauntier.

The enormous, unexpected success of The Birth of a Nation (1915)

contributed to a rush of investment in the production of longer lms,

with the number of releases peaking in 1917 at nearly 1,000 features.

This increase in production led to an oversupply of product, and the

resulting reduction in rental prices fed the growing numbers of the-

aters and the rapid turnover of programs. Many small-town theaters

presented a program of a feature and shorts on a bill that changed

each day. This booking practice had an inevitable eect upon quality,

as Universal cofounder Pat Powers noted in a letter in 1917:

The number of pictures required by the various exhibitors, so that

they will not be compelled to run the same picture the second

time, no matter how good it might be, forces a great deal of stu

on the market which is not interesting or entertaining. … The lack

of the proper story has forced the picture producer to tie to the

star, with the result that, the star, being exploited in this manner,

naturally walks away with the prots. But, as stated, I have come

to the conclusion that all things adjust themselves in time, and I

presume the moving picture business will be no exception.

32

One impact of that adjustment was that “lm companies, which

had been founded in virtually every state of the Union, from Maine

to Florida, from Ithaca to Oregon, gravitated slowly but surely to

Los Angeles,” Jan-Christopher Horak wrote. “In Hollywood lm

producers increasingly nanced their operations through loans from

distributors and/or the owners of massive chains of movie theaters,

forcing lm producers to relinquish some of their independence.”

33

Film production and theater ownership consolidated in an oligopoly

of a small number of large companies, which could then reduce out-

put and charge higher prices on fewer, more protable, lms.

The 1921–22 national recession caused the bankruptcy of