sustainability

Review

Peer Assessment in Physical Education: A Systematic

Review of the Last Five Years

Daniel Bores-García

1

, David Hortigüela-Alcalá

2,

* , Gustavo González-Calvo

3

and

Raúl Barba-Martín

4

1

Department of Physical Therapy, Occupational Therapy, Rehabilitation and Physical Medicine, Faculty of

Health Sciences, Rey Juan Carlos University, 28922 Alcorcón, Madrid, Spain; daniel.bor[email protected]

2

Department of Specific Didactics, Faculty of Education, University of Burgos, 09001 Burgos, Spain

3

Department of Didactics of Musical, Artistic and Body Expression, Faculty of Education of Palencia,

University of Valladolid, 34004 Palencia, Spain; [email protected]

4

Department of Physical Education and Sport, University of Le

ó

n, 24007 Le

ó

n, Spain; [email protected]

* Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +34-947-259-517

Received: 24 September 2020; Accepted: 4 November 2020; Published: 6 November 2020

Abstract:

Purpose: A systematic review of the use of peer assessment in Physical Education in

the last five years (2016–2020). Method: Four databases were used to select those articles that

included information on peer assessment in Physical Education in the different educational stages.

According to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA)

guidelines, including the PICO (participants, intervention, comparators, and outcomes) strategy,

after the exclusion criteria, 13 articles were fully assessed based on seven criteria: (1) year and

author; (2) country; (3) educational stage; (4) type of paper; (5) purpose; (6) content; and (7) outcomes.

Results: the results show that the research was geographically dispersed, although Spain and the

USA had half of the articles reviewed. The research was carried out at all educational stages,

although a greater focus was observed in higher education than in primary and secondary education.

Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed research was almost equally represented, and dealt mainly with

sports and games. Regarding the goals of the studies, a diversity of research so great that it produced

a lack of continuity and coherence in the literature on the subject was found. The research results

on the use of peer assessment showed an increase in the level of motivation, perceived teaching

confidence and competence, and teaching self-efficacy. More research is needed on the benefits of the

use of peer assessment on the self-regulation of learning and the critical thinking of students.

Keywords:

formative assessment; peer assessment; physical education; systematic review;

educational research

1. Introduction

The role of assessment has increased in recent years in the field of education [

1

]. There have been

many publications, scientific conferences, and training sessions on it, but the transfer to the educational

reality is not always easy and the truth is that certain conceptual errors still exist, such as, for example,

the indiscriminate use of the concepts of assessment and scoring as if they were one and the same

thing [

2

]. One of the skills expected of a teacher is his or her ability to evaluate the teaching-learning

process [

3

,

4

], necessarily relating assessment activities to planned activities in order to give meaning

to the whole pedagogical process [

5

]. Such is the importance given to evaluation that some authors

consider that the first and most important change to be made at the methodological level for a global

transformation of the teaching-learning process has to do with the implementation of formative

assessment [6,7] in substitution of the more traditional assessment with a summative approach.

Sustainability 2020, 12, 9233; doi:10.3390/su12219233 www.mdpi.com/journal/sustainability

Sustainability 2020, 12, 9233 2 of 15

1.1. Formative Assessment: A Key Element for Learning

Formative assessment is any evaluative process that aims to improve the teaching-learning process

in its three lines of intervention: improving learning and evidence of student learning, improving the

teaching process of the teacher, and, finally, improving the teaching-learning process in a progressive

way, correcting and refining the procedures carried out in it [

8

–

10

]. Brown and Pickford [

11

] define

it as the process used to recognize and respond to student learning and thus reinforce it during the

teaching-learning process. In this way, assessment acts as a tool for student self-knowledge and

the improvement of all educational processes [

12

]. However, assessment in itself does not produce

beneficial effects if it is not given special treatment, so it has to be approached in an intentional

pedagogical way in the classroom in order to generate competences in the students [

13

]. To do

this, and in order to incorporate assessment into action structures based on the motivation of the

students, it is essential to involve them actively in the assessment procedure [

14

]. In this sense,

the implementation of formative and shared assessment processes has shown a greater awareness of

what students learn, as well as a greater capacity to self-regulate their tasks over time [

15

]. Here the

concept of triadic assessment arises, understood as a triple assessment approach which combines

self-assessment, peer assessment, and teacher assessment, in the same instrument, before a final grade,

and on a given assessment procedure [16].

The formative assessment processes are shown to be ideal for the use of assessment as a tool which

favors self-regulation and awareness of learning by the student and the extrapolation of learning to a

variety of contexts [

17

]. Hortigüela-Alcal

á

, P

é

rez-Pueyo, and Gonz

á

lez-Calvo [

2

] highlight five reasons

for applying formative assessment: Firstly, the student improves his/her awareness of learning when

he/she participates in the assessment process. Secondly, it favors the self-regulation of learning by

influencing the organizational capacities of the students, as already pointed out by Meusen-Beekman,

Joosten-ten Brinke, and Boshuizen [

18

]. Thirdly, it makes it possible to apply learning to other different

contexts outside the classroom since, as Joughin, Dawson, and Boud [

19

] comment, knowing in depth

personal limitations and possibilities facilitates the transfer of learning from knowledge to know-how.

Fourthly, there is an increase in feedback channels, which enriches the information that reaches the

student as it comes from different sources and not only from the teacher [

20

]. Finally, the use of

formative assessment improves teaching practice, since, as Wei [

21

] points out, the teacher reflects

on the impact that teaching is having on students and, therefore, what they should do to improve

the process.

1.2. Peer Assessment: Giving Students Responsibility in the Assessment Process

In addition to the need for evaluation to be formative, many authors point out that it should

be shared [

22

–

25

], thus encouraging student participation throughout the process and increasing

their awareness of what they are learning. As is the case with educational assessment in general,

peer assessment only makes sense when it is learning-oriented; hence authors such as Kepell et al. [

26

]

use the concept of learning-oriented peer assessment. Assessment must stop being an individual and

imposed process and become a dialogue in which students play an important role from the point

of view of decision-making [

27

]. According to these authors, the three most common techniques

for carrying out shared assessment processes are self-assessment, dialogue evaluation, and peer

assessment. Peer assessment is a very useful learning strategy to improve the feedback process in

students [

28

], encouraging critical thinking [

29

]. This concept, coined at the end of the last century [

30

],

gives students the role of evaluator and advisor at the same time as the peers are carrying out the

proposed activities.

Numerous articles have been published in recent years showing some of the advantages of

this evaluation strategy. Studies show the effectiveness of peer assessment in increasing students’

active participation, motivation level, and improvement in learning attitudes [

31

,

32

]. Furthermore,

the use of peer assessment improves students’ capacity for reflection and commitment and reduces the

teacher’s burden, thus allowing teachers to pay more attention to other important factors [

33

],

as well as

Sustainability 2020, 12, 9233 3 of 15

facilitating a better use of time when students participate in assessment processes in large classes [

34

].

According to Chetcuti and Cutajar [

35

], it also favors processes of self-assessment, self-government,

and enhances the higher-level thinking skills. Authors such as Nicol, Thomson, and Breslin [

36

] add

that providing feedback to classmates generates even greater benefit than just receiving it, as it triggers

higher-order processes from a cognitive point of view, such as diagnosing problems and suggesting

solutions. A recent systematic review concludes that the use of peer assessment has a positive impact

on academic performance, over and above traditional teacher assessment, although with levels similar

to self-assessment [

37

]. However, another recent meta-analysis [

38

] shows that, from a learning point of

view, there are only significant benefits in the use of peer assessment when both teachers and students

have been previously trained in such a way that the essential procedures and mechanisms of this type

of assessment are known.

1.3. Peer Assessment in Physical Education: A Gap in Literature

In recent years, successful practices on the use of formative and shared assessment in the area of

Physical Education (PE) have been disseminated [

10

] within the framework of the international concept

of alternative assessment [

23

], as opposed to traditional assessment. The emphasis is on assessment

which contributes to the generation of significant learning by allowing the participation of students

throughout the teaching-learning process [7].

Nevertheless, from the area of PE little research has been carried out that deals with peer assessment

as an evaluation procedure integrated into the current of formative evaluation. Peer assessment is

presented as a shared evaluation mechanism that encourages student participation and promotes

learning by allowing greater awareness of the evaluation criteria and even participation in their

elaboration [

2

]. Students evaluate their peers, acquiring a role of observer and evaluator that broadens

their vision of the teaching-learning process. Guidelines have been proposed for the implementation

of peer assessment in the subject of PE in the educational context [

39

,

40

], and field research has

been carried out in which positive results have been obtained, such as the increase in motivation

for content [

41

], in the level of confidence in secondary education students [

42

], and in the initial

training of future teachers [

43

]. However, the vast majority of articles published in the last twenty

years deals with formative and shared assessment together, integrating peer-assessment processes

within other more general ones and coexisting in almost all cases with self-assessment [

44

–

49

], in such

a way that it is difficult to establish to which specific assessment procedure the results obtained in all

this research are due. It is for this reason that we believe it is essential to analyze the real impact on

learning that the use of peer assessment has on PE students, isolating this type of shared assessment

from other associated mechanisms such as self-assessment or teacher assessment. Although some

reviews on assessment in the general educational context have been published in recent years [

50

–

54

],

including a systematic review on the use of alternative assessment in PE [

23

], to date, as far as we have

been able to ascertain, there is no systematic review addressing peer assessment in the context of PE,

so the aim of this paper is to conduct a review of the scientific literature published over the last five

years (2016–2020) on peer assessment in PE. Therefore, this research focuses specifically on student

evaluation and student involvement in it, contributing directly both to the concept of sustainability

of the journal itself and to the thematic line of the Special Issue on evaluation in education from a

sustainability perspective.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Sources

The present paper consists of a systematic review of articles published in the last five years

on the use of peer assessment in PE. Papers published between January 2016 and September 2020

were searched in four electronic databases: SCOPUS, ERIC, Web of Science, and Taylor and Francis.

The descriptors “Peer assessment” and “Physical education” were used with the search operator AND.

Sustainability 2020, 12, 9233 4 of 15

2.2. Exclusion Criteria

The exclusion criteria used were as follows: (1) Duplicated articles, (2) Articles not published in

journals indexed in the Journal Citation Report (JCR) or the Scimago Journal Rank (SJR), (3) Articles

in languages other than English or Spanish, and (4) Articles using peer assessment in contexts other

than PE.

2.3. Limits and Methodology of the Search

The search was conducted following the guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic

Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) [

55

], including the PICO strategy: Participants (e.g., primary,

secondary, country), Intervention (e.g., content, type of research), Comparators (e.g., Peer Assessment,

Physical Education), and Outcomes.

2.4. Procedure

The research began on 10 September 2020 and ended on 30 September 2020. Firstly, the criteria

for selecting the articles that could be part of the review were drawn up, as well as the selection of

exclusions and the databases in which to carry out the bibliographic search. As for the inclusion criteria,

after a review of the scientific literature on the subject, we found that the term “peer assessment”

is fully accepted and widespread. Since the focus of the review was not on formative assessment

procedures in general, but on peer assessment, it was decided to use this term. To this was added the

term “physical education” to limit the search to that context only. Those articles that dealt with peer

assessment in areas other than physical education were discarded. After completing the process of

defining the inclusion and exclusion criteria, the selection of the databases for the bibliographic search

was carried out. Four databases were selected for the following reasons. ERIC was chosen because it is

the online database with the most articles in the field of education. SCOPUS and WEB OF SCIENCE

are the two most important citation databases in the world and are highly regarded by the scientific

community, so researchers considered it essential to include them in the review. Taylor and Francis

was selected for its strong worldwide presence and for having over 2600 journals in its database.

All articles were extracted from the databases and analyzed through the MEDELEY software.

With the inclusion criteria, initially, 104 publications were found using the mentioned descriptors:

68 articles from Taylor and Francis, 20 articles from ERIC, 7 articles from SCOPUS, and 9 articles from

Web of Science (Figure 1). The analysis of the articles was carried out by two researchers, who worked

independently, respecting the criteria of inclusion and exclusion. At the end of the work they shared

the results. After the second phase of exclusion, in which those articles that dealt in a general way

with formative or shared assessment, but without explicitly naming peer assessment, were discarded,

only 13 articles remained. The most complex phase was this second one, since in the databases there

were several articles that contained the concept of peer assessment in their abstract or keywords but,

after a careful reading of the whole text, it was found that they did not refer to this type of assessment

in particular, but rather dealt with assessment for learning, formative assessment, or self-assessment in

a generic way, without going into detail or quoting peer assessment in particular. This is the reason

why 18 other articles were discarded, leaving only 13.

Sustainability 2020, 12, 9233 5 of 15

Sustainability 2020, 12, x FOR PEER REVIEW 5 of 15

field research in which the peer assessment process has been implemented and concrete results are

obtained. (5) Purpose: the objective of the study. (6) Content: it details the curricular content around

which the research is developed when it has a more limited duration, or it states that it is research

that covers a complete school year in which many contents are developed. (7) Outcomes: this last

category describes the main results of the research. It should be noted that this last category does not

make sense for articles with a theoretical focus, as they do not show the results of research.

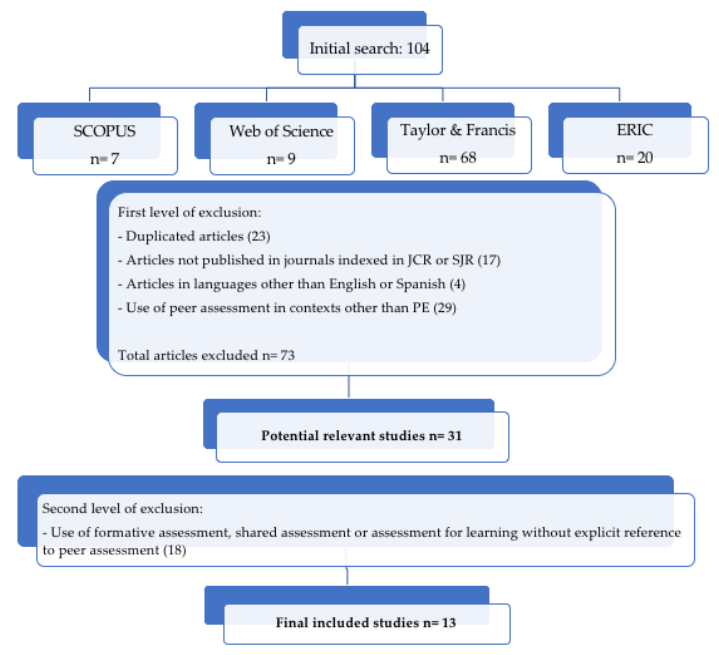

Figure 1. Flow diagram of the systematic search process.

2.5. Quality Assessment

To ensure that the selected articles, following the inclusion and exclusion criteria, were of

sufficient quality to be considered in the present review, three procedures were carried out. First, the

review was included in the Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) register, an

international database for systematic reviews. This database records and maintains permanently the

key features of the review protocol. Second, the PRISMA guidelines [55] were used to assess the

quality of this systematic review. PRISMA includes an evidence-based set of items to report the

quality of meta-analyses and systematic reviews. In addition, the A MeaSurement Tool to Assess

systematic Reviews (AMSTAR) 2 critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews [58] was used. Third,

the criteria for assessing the quality of the selected studies were based on the Consolidated Standards

of Reporting Trials Statement [59], the Checklist for Measuring Study Quality [60], and the

Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies Statement [61].

Figure 1. Flow diagram of the systematic search process.

Table 1 was drawn up with the 13 final articles selected, following a systematic and thorough review

process, in which each was described on the basis of the following categories, taken from previous

systematic reviews [

56

,

57

]. (1) Author and year of publication: this category shows information about

the authors of each article and the years in which the publications were made, over the last five years.

(2) Country of application of the model: it shows the countries in which the research was carried

out, regardless of the country of origin of the authors or the place where the publisher of the journal

in which the article is published is located. (3) Educational stage: this category details whether the

article is contextualized for the primary education, secondary education, or higher education stage,

or whether it has a general orientation for any stage. (4) Type of paper: includes information about the

type of article, as it can be an article with a theoretical approach or a field research in which the peer

assessment process has been implemented and concrete results are obtained. (5) Purpose: the objective

of the study. (6) Content: it details the curricular content around which the research is developed

when it has a more limited duration, or it states that it is research that covers a complete school year in

which many contents are developed. (7) Outcomes: this last category describes the main results of the

research. It should be noted that this last category does not make sense for articles with a theoretical

focus, as they do not show the results of research.

Sustainability 2020, 12, 9233 6 of 15

Table 1. Summary of articles about peer assessment in PE published between 2016 and 2020.

Author and Year Country Educational Stage Type of Paper Purpose Content Outcomes

Aarskog (2020) Norway

Primary and

Secondary

Theoretical

To investigate the process of student

participation in PE assessment.

All the curricular

contents, in general

No research results as it is an article with a

theoretical approach.

Alstot (2020) USA Primary Education

Research paper: qualitative

approach. Video recording

To determine the extent to which

primary school students correctly

carry out evaluation processes of

different launches.

Throwing skills

Students are able to carry out a fairly

accurate peer review process after having

had the opportunity to receive training even

if it is for short duration.

Asun-Dieste, Romero-Martin,

Aparicio-Herguedas,

and Fraile-Aranda (2020)

Spain Higher Education

Research paper: qualitative

approach. Self-reports

To examine proxemic difficulties

when leading physical

activity sessions.

General

physical activities

Four categories: Teacher orientation and

position; group position and organization;

teacher movement; and physical and

affective distance-immediacy established

between teacher and students.

Canadas, Castejon,

and Santos-Pastor (2018)

Spain Higher Education

Research paper: qualitative

approach. Questionnaire

To assess the perception of

participants about assessment

applied in initial training and the

participation in grading.

All the contents in

a college year

(a) Primary Teaching in Physical Education

Degree participants perceive they have a

greater previous knowledge of the

assessment system and assessment tasks,

greater participation in the development of

assessment tests, and a greater use of

participatory grading forms than Physical

Activity and Sport Sciences participants;

(b) in both Degrees, university teachers

show higher values for all the participatory

grading forms than graduates; and

(c) participatory grading forms are directly

related to most of the assessment items

studied in both Degrees.

Eather, Riley, Miller,

and Bradley (2017)

Australia Higher Education

Research paper: qualitative

approach. Questionnaire

To explore the use of peer dialogue

assessment as a learning resource

with students studying Physical

Education at university.

Invasion games

Students show significant development in

the perception of confidence, self-efficacy,

and their level of competence in teaching.

Eather, Riley,

and Miller (2019)

Australia Higher Education

Research paper: quantitative

approach. Two-arm randomized

controlled trial

To test the effectiveness of two

different methods of feedback from

dialogue: peer dialogue assessment

and dialogical feedback carried out

by a university teacher with students

of PE in higher education.

Several games

and sports

Both groups showed the same significant

improvement in teaching competence and

confidence, as well as in the perception of

self-efficacy.

Sustainability 2020, 12, 9233 7 of 15

Table 1. Cont.

Author and Year Country Educational Stage Type of Paper Purpose Content Outcomes

Flynn, Duell, Dehaven,

and Heidorn (2017)

USA All the stages Theoretical

To provide techniques, strategies,

and ideas for physical educators and

swim instructors to engage

swimmers at all levels using the Kick,

Stroke, and Swim (KSS) program.

Swimming

No research results as it is an article with a

theoretical approach.

Kuo, Chen, Chu, Yang,

and Chen (2017)

Taiwan

Primary and

Secondary

Research paper: quantitative

approach. Tests

To develop a mobile learning system

for a Kung Fu Tai-Chi PE course

through a peer-assessment mobile

PE approach.

Kung Fu Tai-Chi

Promotion of students’ learning interest and

motivation and improvement of their

learning self-efficacy and socialization.

López-Pastor,

Pérez-Pueyo, Barba,

and Lorente-Catalán (2016)

Spain Higher Education

Research paper: qualitative

approach. Questionnaire

and interviews

To learn the importance and

functionality that assessment rubrics

used in written group tasks have for

teachers in initial training.

Written group

assignments

(a) it is easier to perform the task in a better

way when the assessment criteria is known

in advance; (b) there were significant

differences in the students’ previous

experiences of peer assessment; and

(c) students showed their will to use

formative assessment in the future.

Macken, MacPhail,

and Calderon (2020)

Ireland Primary

Research paper: qualitative

approach. Field notes, reflective

journals, and interviews

To examine the extent that primary

PSTs demonstrate assessment

literacy in their enactment of AfL

while teaching PE.

All the curricular

contents, in general

The use of teacher educator modelling,

mentoring, and scaffolding with primary

school students, during upskill sessions and

in-situ during the PST school placements,

enhanced the PSTs’ assessment literacy in

the enactment of AfL in primary PE to a

greater extent than when implemented

during the module with their PST peer.

Martos-García, Usabiaga,

and Valencia-Peris (2018)

Spain Higher Education

Research paper: mixed approach.

Questionnaire and test

To analyze the differences of

perception between two groups

of students when undergoing a

formative and peer assessment

process through the use of

the blogosphere.

Basque pelota and

Valencian pilota

Basque students were more satisfied with

the assessment tool used than the Valencian

students. In both groups they point to the

motivating and functional component of the

blogosphere in contrast to other more

traditional evaluation systems.

Michael and Webster (2020) USA

Primary and

Secondary

Theoretical

To introduce the Pickleball

Assessment of Skill and

Tactics (PAST).

Pickleball

No research results as it is an article with a

theoretical approach.

Soytürk (2019) Turkey Higher Education

Research papers: quantitative

approach. Observation forms

To analyze efficiency of teacher

candidates in movement analysis,

self-evaluation, and peer evaluation

for four basic volleyball skills.

Volleyball

The teacher candidates’ scores for

self-evaluation of their skills and their peers’

scores were found to be correlated.

Sustainability 2020, 12, 9233 8 of 15

2.5. Quality Assessment

To ensure that the selected articles, following the inclusion and exclusion criteria, were of sufficient

quality to be considered in the present review, three procedures were carried out. First, the review was

included in the Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) register, an international

database for systematic reviews. This database records and maintains permanently the key features

of the review protocol. Second, the PRISMA guidelines [

55

] were used to assess the quality of

this systematic review. PRISMA includes an evidence-based set of items to report the quality of

meta-analyses and systematic reviews. In addition, the A MeaSurement Tool to Assess systematic

Reviews (AMSTAR) 2 critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews [

58

] was used. Third, the criteria for

assessing the quality of the selected studies were based on the Consolidated Standards of Reporting

Trials Statement [

59

], the Checklist for Measuring Study Quality [

60

], and the Strengthening the

Reporting of Observational Studies Statement [61].

3. Results and Discussion

The 13 articles selected between January 2016 and September 2020 are discussed around the seven

elements used in the categorization set out in Table 1. The year is not included in the discussion as

they are all from the last five years.

3.1. Country

In order to know the degree of dissemination of the peer assessment in PE throughout the world,

this category has been included in the analysis. The results show a variety in the countries where

research has been carried out on the use of peer assessment in PE. Four continents are represented,

although more than half of the publications have been made in the USA (three articles) and Spain

(four articles). The amount of research carried out in these two countries is significant, as it is carried

out by different research groups belonging to different universities all over the countries. However,

the volume of articles on this subject published in Spain and in the USA is not surprising, as both

countries have been working on educational assessment in PE for more than twenty years. In 2007,

an article was published in which the path followed in Spain towards the construction of quality

formative assessment in PE since the end of the 20th century was described [

62

], and in the USA there

is a long tradition of the use of assessment for learning influenced to a great extent by the policies of

the Welsh government exported to the other side of the ocean [

63

]. Australia has two publications by

the same research team with a very similar focus, with only two years’ difference between one article

and the other. Norway, Taiwan, Ireland, and Turkey complete the remaining four articles.

3.2. Educational Stage

In terms of the educational stage on which the publications reviewed focus, the results are

heterogeneous. Except for the article by Flynn, Duell, Dehaven, and Heidorn [

64

], whose focus is on

swimmers of any age, the rest of the publications explicitly express the educational stage to which

they refer. Seven of the thirteen articles are contextualized in higher education, geared towards future

PE teachers or sports coaches. This result is the consequence of a wide dissemination of research on

formative assessment in higher education in recent years, both online [

65

,

66

] and face-to-face [

67

–

69

],

and greater facility for researchers to investigate in the context in which they work on a daily basis.

The remaining five articles focus on PE practice at the primary (6–11 years old) and secondary

(12–18 years old) stages. Traditionally, assessment methods that allow for objective measurement,

such as tests and physical protocols, have been very present in PE, showing a lack of understanding of

the objective associated with learning that any evaluation process should have [

11

,

12

] and generating

a certain reluctance on the part of teachers to apply assessment procedures that are less simple to

quantify or measure [

70

,

71

], although in recent years an approach to alternative methods has been

observed [

72

]. The inclusion of this category of analysis supports the argument that there is a need

Sustainability 2020, 12, 9233 9 of 15

to broaden and deepen research on the use of peer assessment in the school context, as there is little

research on the early stages of education.

3.3. Type of Paper

In the inclusion and exclusion criteria, it was decided not to limit the review to research articles,

as it was considered interesting to explore the methodological orientation of publications on peer

assessment in PE. The results show that three of the thirteen articles have a theoretical approach, so they

do not use a sample from which an experiment is carried out and from which results are extracted to be

analyzed. It is surprising how few theoretical articles exist given the importance of the subject matter

and its direct influence on learning [

12

]. The article by Aarskog [

73

] deals with student participation in

shared assessment processes, based on the theory of Black and William [

74

] and comparing it with the

educational reality of Norway. Michael and Webster [

75

] propose a shared assessment instrument for

Pickleball content (Pickleball Assessment of Skill and Tactics (PAST)), while Flynn, Duell, Dehaven,

and Heidorn [

64

] present a program called Kick, Stroke, and Swim (KSS) for teaching swimming,

giving practical ideas for assessing learning in a shared way. As for the eleven research articles included

in the review, six of them have a qualitative approach, using various data collection instruments such as

questionnaires [

76

–

78

], semi-structured interviews [

78

,

79

], self-reports, and reflective journals [

79

,

80

]

or video-recording [

81

]. Three articles use a quantitative methodology through the application of

tests [

28

], observation forms [

82

], and self-reports whose data were treated quantitatively in a two-arm

randomized trial design [

83

]. Martos-Garc

í

a, Usabiaga, and Valencia-Peris [

84

] propose a mixed design

for which they use both questionnaires and tests. The fact that there are more qualitative articles

than quantitative ones points to a trend towards the use of less positivist approaches in the world of

educational research, traditionally taken up by quantitative approaches [

85

,

86

] in which the aim is to

find evidence rather than to understand the phenomena that take place in the educational context.

3.4. Purpose and Content

The heterogeneity present in the articles included in the review is also shown in the purpose they

pursue and the content in which they develop the discourse. On the one hand, we find several articles in

which the central content is a sport or a set of sports, pursuing for each of them very different purposes.

The article by Michael and Webster [

75

] aims to present an assessment instrument, to be used among

students, of the technical-tactical aspects of Pickleball. Flynn, Duell, Dehaven, and Heidorn [

64

] focus

on providing strategies and techniques to increase swimmers’ commitment using the Kick, Stroke, and

Swim program, as the benefits of using shared assessment on motivation have been demonstrated [

41

].

Kuo, Chen, Chu, Yang, and Chen [

28

] have as their main objective to develop a mobile learning system

for a Kung Fu Tai-Chi PE course through a peer-assessment mobile PE approach. Martos-Garc

í

a,

Usabiaga, and Valencia-Peris [

84

] compare the perception of two groups of students from two different

universities about the use of formative and shared assessment strategies through the blogosphere to

evaluate the learning of the essential aspects of two traditional sports in the cities where the research

was carried out: Basque pelota and Valencian pilota. Soytürk’s paper [

82

] analyzes the efficiency of the

use of formative assessment and peer assessment by future PE teachers to evaluate the learning of four

volleyball techniques. Research by Eather, Riley, Miller, and Bradley [

76

] seeks to explore the benefits

of using peer dialogue assessment in different invasion games. Two years later, these same authors [

83

]

compare the effects of the use of peer dialogue assessment with those of dialogical feedback provided by

an academic in different sports games. The works of Asun-Dieste, Romero-Mart

í

n, Aparicio-Herguedas,

and Fraile-Aranda [

80

], of Aarskog [

73

], and of Macken, MacPhail, and Calder

ó

n [

79

] are not based on

a specific content either, but deal with different contents of the curriculum, although with different

purposes: while the first article seeks to detect the difficulties from a proxemic point of view that

occur when leading physical activity classes, the other two focus on how students participate in the

assessment of their own learning as a starting point, since only a correct use of shared assessment

can produce beneficial effects on learning [

38

]. The fact that some articles deal with the use of peer

Sustainability 2020, 12, 9233 10 of 15

assessment in all curricular content shows the great transversality and applicability of the use of

formative assessment [2].

3.5. Outcomes

Although the thirteen articles included in the review include peer assessment in PE in one form

or another, not all of them have assessment as their main subject. This is the case with the article

by Asun-Dieste, Romero-Mart

í

n, Aparicio-Herguedas, and Fraile-Aranda [

80

], whose purpose is to

identify the spatial difficulties generated in the development of the direction of a physical activity

session, categorizing the results into four groups: teacher orientation and position, group position and

organization, teacher movement, and physical and affective distance-immediacy established between

teacher and students. Therefore, in this paper the peer assessment is used as an instrument to achieve

the objectives of the research, not as an end of it. The three articles with a theoretical focus have

not been included in this category, since they do not generate results from field research. The other

nine articles do generate results related to formative assessment in general and to peer assessment

in particular. Two articles [

28

,

84

] show among their results an increase in student motivation after

the use of peer assessment processes, in line with Santana, Bedoya, and Robles [

41

]. The two works

from Australia [

76

–

83

] show that the use of peer assessment produces an improvement in perceived

teaching confidence and competence, and teaching self-efficacy, coinciding with the results of previous

research [

42

,

43

]. As reflected in the scientific literature, peer assessment produces an improvement

in learning awareness [

2

,

19

]. Similar results were obtained in the article by Canadas, Castej

ó

n,

and Santos-Pastor [

77

], whose participants were able to culminate the peer-assessment process with the

rating of their peers. In the research by L

ó

pez-Pastor, P

é

rez-Pueyo, Barba, and Lorente-Catal

á

n [

78

],

it is concluded that previous knowledge of the assessment instrument is essential, since, although the

use of rubrics or other instruments favors the development of the process, the previous experiences

of the students with the formative and shared assessment are decisive, in line with the work of Li,

Xiong, Hunter, Guo, and Tywoniw [

38

], as the students expand their awareness of learning by being

responsible for it [

2

]. This is precisely the conclusion reached by Alstot [

81

] in his work, showing that the

students are capable of making a correct evaluation of the learning of their peers after a sufficiently long

process of training in the formative and shared-assessment procedures. Soytürk’s [

82

] research shows

a high correlation between the results obtained through peer assessment and through self-assessment,

coinciding with Krause, O’Neil, and Dauenhauer [

49

] and with Chr

ó

in

í

n and Cosgrave [

48

], since both

procedures depend largely on previous training and experience [

38

]. This result is particularly favorable

for time management by the teacher, since, if students participate in the assessment process, it can

facilitate the teacher’s work and allow more time to be spent on the most pressing issues [

33

,

34

].

Another result of the application of peer assessment is the increase of socialization, as detailed in two of

the research studies reviewed [

28

,

84

], since dialogue between students is required [

27

] and interaction

between all participants in the process is increased [

25

]. No results have been found that refer to the

self-regulation of learning through the use of peer assessment [

15

,

17

,

18

] or to the development of

critical thinking [29].

4. Conclusions

The review carried out shows that little research has been done in recent years on the use of

peer assessment in PE. The existing bibliography on the use of formative or alternative assessment

is extensive and includes the shared-assessment approaches within which peer assessment is found.

However, as seen in this review, few articles address peer assessment in PE specifically, making it

difficult to identify to which of all formative assessment processes the results shown in the research

are due. Only thirteen articles have been published and only ten of them are field research. The two

countries that have done most research on the subject are the USA and Spain, with more than half of

the total publications in the last five years. This shows the need to further internationalize research on

formative and shared evaluation. There is an effort to investigate the benefits of shared assessment

Sustainability 2020, 12, 9233 11 of 15

at the university level, but much more research is needed in the primary and secondary school

context. It is essential that the university approaches the school context in order to obtain the most

reliable information possible on what is happening in the teaching-learning process. Only through

a real transfer from theory to educational practice can the desired dynamics be changed, and it is

essential that research efforts are directed towards a transformation of educational reality throughout all

stages. The methodological approach is quite heterogeneous, with qualitative, quantitative, and mixed

research, and with much diversity in the purposes of the studies. This lack of continuity in research

results in a great variety of results that cannot be compared with other similar studies, in addition to

generating gaps in knowledge that have not been covered until now, such as the effects of the use of

peer assessment on the self-regulation of learning and the development of critical thinking or motor

skills. There are studies that show these benefits in other areas of knowledge, but there is a lack of

scientific evidence applied to PE.

The main contribution of this work is to provide the scientific literature with the first review on the

use of peer assessment in PE, since until now none existed. Furthermore, a very complete information

is offered, divided into different categories, which can serve as an aid for future reviews on assessment

in PE.

As a line of future research and given the large number of unaddressed aspects in the scientific

literature that this review has left in evidence, it would be interesting to carry out research in schools in

which the benefits of the use of peer assessment on self-regulation of learning, on critical thinking,

and on learning by students are proven. It is essential that teachers can research and reflect on their

own practice in order to increase scientific and practical evidence on formative assessment in general

and peer assessment in particular in the context of PE. Research on the use of formative and shared

assessment in general and on peer assessment in particular shows the great impact that these processes

have on learning, so it is essential to explore the extent to which these benefits occur when peer

assessment is applied in school PE. Students cannot simply be receiving agents of contents but must be

part of the teaching-learning process in order to be able to self-regulate their progress, to know the

reason for the activities they carry out, and to understand the evaluation criteria that will verify the

learning and contribute to improve the process to achieve an optimal development of their physical,

cognitive, affective, and social potential.

Author Contributions:

Conceptualization, D.B.-G. and D.H.-A.; methodology, D.B.-G., D.H.-A., and R.B.-M.;

software, G.G.-C.; validation, D.H.-A., R.B.-M., and G.G.-C.; formal analysis, D.B.-G.; investigation, D.B.-G. and

D.H.-A.; writing—original draft preparation, D.B.-G.; writing—review and editing, D.H.-A., R.B.-M., and G.G.-C.;

supervision, R.B.-M. and G.G.-C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding: This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

1.

DeLuca, C.; Valiquette, A.; Coombs, A.; LaPointe-McEwan, D.; Luhanga, U. Teachers’ approaches to

classroom assessment: A large-scale survey. Assess. Educ. Princ. Policy Pract. 2018, 25, 355–375. [CrossRef]

2.

Hortigüela-Alcal

á

, D.; P

é

rez-Pueyo,

Á

.; Gonz

á

lez-Calvo, G. Pero

. . .

¿a qu

é

nos referimos realmente con

evaluaci

ó

n formativa y compartida? Confusiones habituales y reflexiones pr

á

cticas. Rev. Iberoam. Eval. Educ.

2019, 12, 13–27.

3. Perrenoud, P. Diez Nuevas Competencias Para Enseñar; Grao: Barcelona, Spain, 2004.

4. Murchan, D.; Shiel, G. Understanding and Applying Assessment in Education; Sage: London, UK, 2017.

5.

Brevik, L.; Blikstad-Balas, M.; Lyngvær-Engelien, K. Integrating assessment for learning in the teacher

education programme at the University of Oslo. Assess. Educ. Princ. Policy Pract.

2017

, 24, 164–184. [CrossRef]

6.

P

é

rez-Pueyo, A.; Hortigüela-Alcal

á

, D.; Guti

é

rrez-Garc

í

a, C. ¿Y si reflexionamos sobre si toda la innovaci

ó

n

es educativa? Cuad. Pedagog. 2019, 500, 87–91.

7.

P

é

rez-Pueyo, A.; Hortigüela-Alcal

á

, D. ¿Y si toda la innovaci

ó

n no es positiva en Educaci

ó

n F

í

sica?

Reflexiones y consideraciones prácticas. Retos 2020, 37, 579–587.

Sustainability 2020, 12, 9233 12 of 15

8.

L

ó

pez-Pastor, V.M. La Evaluaci

ó

n Formativa y Compartida en Educaci

ó

n Superior: Propuestas, T

é

cnicas, Instrumentos

y Experiencias; Narcea: Madrid, Spain, 2009.

9.

L

ó

pez-Pastor, V.M.; P

é

rez-Pueyo,

Á

. Buenas Pr

á

cticas Docentes: Evaluaci

ó

n Formativa y Compartida en Educaci

ó

n:

Experiencias de Éxito en todas las Etapas Educativas; Universidad de León: León, Spain, 2017.

10.

L

ó

pez-Pastor, V.M.; Hamodi, C.; L

ó

pez, A.T. Evaluaci

ó

n formativa y compartida en educaci

ó

n:

Buenas pr

á

cticas y experiencias y experiencias desarrolladas por la Red de Evaluaci

ó

n Formativa. In

Buenas Pr

á

cticas de Evaluaci

ó

n de Aprendizajes en Educaci

ó

n Superior; Pavi

é

, A., Casas, M., Eds.; Ministerio de

Educación: Santiago de Chile, Chile, 2016; pp. 13–43.

11.

Brown, S.; Pickford, R. Evaluaci

ó

n de Habilidades y Competencias en Educaci

ó

n Superior; Narcea:

Madrid, Spain, 2013.

12.

Calkins, A.; Conley, D.; Heritage, M.; Merino, N.; Pecheone, R.; Pittenger, L.; Udall, D.; Wells, J. Five Elements

for Assessment Design and Use to Support Student Autonomy. Students at the Center: Deeper Learning

Research Serie. Jobs Future 2018, 25, 12–14.

13.

Hortigüela-Alcal

á

, D.; Palacios, A.; L

ó

pez-Pastor, V. The impact of formative and shared or coassessment

on the acquisition of transversal competences in higher education. Assess. Eval. High. Educ.

2019

, 44,

933–945. [CrossRef]

14.

Tolgfors, B. Transformative Assessment in Physical Education. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev.

2019

, 25,

1211–1225. [CrossRef]

15.

Jing, M. Using Formative Assessment to Facilitate Learner Self-Regulation: A Case Study of Assessment

Practices and Student Perceptions in Hong Kong. Taiwan J. TESOL 2017, 14, 87–118.

16.

P

é

rez-Pueyo, A.; Hortigüela-Alcal

á

, D.; Guti

é

rrez, C.; Hernando-Garijo, A. ¿Andamiaje y evaluaci

ó

n

formativa: Dos caras de la misma moneda? Inf. Educ. Aprendiz. 2019, 5, 559–565. [CrossRef]

17.

Chng, L.S.; Lund, J. Assessment for Learning in Physical Education: The What, Why and How. J. Phys. Educ.

Recreat. Danc. 2018, 89, 29–34. [CrossRef]

18.

Meusen-Beekman, K.D.; Joosten-ten Brinke, D.; Boshuizen, H. Developing Young Adolescents’ Self-Regulation

by Means of Formative Assessment: A Theoretical Perspective. Cogent Educ. 2015, 2, 107–123. [CrossRef]

19.

Joughin, G.; Dawson, P.; Boud, D. Improving Assessment Tasks through Addressing Our Unconscious Limits

to Change. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2017, 42, 1221–1232. [CrossRef]

20.

Wanner, T.; Palmer, E. Formative Self- and Peer Assessment for Improved Student Learning: The Crucial

Factors of Design, Teacher Participation and Feedback. Assess. Eval. High. Educ.

2018

, 43,

1032–1047. [CrossRef]

21.

Wei, W. Using summative and formative assessments to evaluate EFL teachers’ teaching performance.

Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2014, 40, 611–623. [CrossRef]

22.

L

ó

pez-Pastor, V.M. Desarrollando sistemas de evaluaci

ó

n formativa y compartida en la docencia universitaria.

An

á

lisis de resultados de su puesta en pr

á

ctica en la formaci

ó

n inicial del profesorado. Eur. J. Teach. Educ.

2008, 31, 293–311. [CrossRef]

23.

L

ó

pez-Pastor, V.M.; Kirk, D.; Lorente-Catal

á

n, E.; MacPhail, A.; Macdonald, D. Alternative Assessment in

Physical Education: A Review of International Literature. Sport Educ. Soc. 2013, 18, 57–76. [CrossRef]

24.

MacPhail, A.; Murphy, F. Too much freedom and autonomy in the enactment of assessment? Assessment in

physical education in Ireland. Ir. Educ. Stud. 2017, 36, 237–252. [CrossRef]

25.

Tolgfors, B.; Ohman, M. The Implications of Assessment for Learning in Physical Education and Health.

Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2015, 22, 150–166. [CrossRef]

26.

Keppell, M.; Au, E.; Ma, A.; Chan, C. Peer learning and learning-oriented assessment in technology-enhanced

environments. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2006, 31, 453–464. [CrossRef]

27.

Barrientos-Hern

á

n, E.; L

ó

pez-Pastor, V.M.; P

é

rez-Brunicardi, D. Why do I do formative and shared assessment

and/or assessment for learning in physical education? Retos 2019, 36, 37–43.

28.

Kuo, F.C.; Chen, J.M.; Chu, H.C.; Yang, K.H.; Chen, Y.H. A peer-assessment mobile Kung Fu education

approach to improving students’ Affective performance. Int. J. Dist. Educ. Technol.

2017

, 15, 1–14. [CrossRef]

29. Topping, K.J. Peer assessment. Theory Pract. 2009, 48, 20–27. [CrossRef]

30.

Topping, K.J. Peer assessment between students in colleges and universities. Rev. Educ. Res.

1998

, 68,

249–276. [CrossRef]

31.

Tsuei, M. Using synchronous peer tutoring system to promote elementary students’ learning in mathematics.

Comput. Educ. 2012, 58, 1171–1182. [CrossRef]

Sustainability 2020, 12, 9233 13 of 15

32.

Van Zundert, M.; Sluijsmans, D.M.A.; Van Merrienboer, J.J.G. Effective peer assessment processes:

Research findings and future directions. Learn. Instr. 2010, 20, 270–279. [CrossRef]

33.

Cho, K.; Schunn, C.; Wilson, R. Validity and Reliability of Scaffolded Peer Assessment of Writing from

Instructor and Student Perspectives. J. Educ. Psychol. 2006, 98, 891–901. [CrossRef]

34.

Vickerman, P. Student perspectives on formative peer assessment: An attempt to deepen learning? Assess. Eval.

High. Educ. 2009, 34, 221–230. [CrossRef]

35.

Chetcuti, D.C.; Cutajar, C. Implementing peer assessment in a post-secondary physics classroom. Int. J. Sci.

Educ. 2014, 36, 3101–3124. [CrossRef]

36.

Nicol, D.; Thomson, A.; Breslin, C. Rethinking feedback practices in higher education: A peer review

perspective. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2014, 39, 102–122. [CrossRef]

37.

Double, K.; McGrane, J.; Hopfenbeck, T. The impact of peer assessment on academic performance:

A meta-analysis of control group studies. Educ. Psych. Rev. 2020, 32, 481–509. [CrossRef]

38.

Li, H.; Xiong, Y.; Hunter, C.V.; Guo, X.; Tywoniw, R. Does peer assessment promote student learning?

A meta-analysis. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2020, 45, 193–211. [CrossRef]

39.

Johnson, R. Peer Assessments in Physical Education. J. Phys. Educ. Recreat. Danc.

2004

, 75, 33–40. [CrossRef]

40.

Ward, P.; Lee, M. Peer-assisted learning in physical education: A review of theory and research. J. Teach.

Phys. Educ. 2005, 24, 205–225. [CrossRef]

41. Santana, M.; Bedoya, J.; Robles, A. Evaluación compartida con fichas de observación durante el proceso de

aprendizaje de las habilidades gimnásticas. Un estudio experimental. Rev. Iberoam. Educ. 2009, 50, 7.

42.

Butler, S.; Hodge, S. Enhancing students trust through peer assessment in physical education. Phys. Educ.

2001, 58, 30–42.

43.

Atienza, R.; Valencia-Peris, A.; Martos-Garc

í

a, D.; L

ó

pez-Pastor, V.M.; Dev

í

s-Dev

í

s, J. La percepci

ó

n del

alumnado universitario de educaci

ó

n f

í

sica sobre la evaluaci

ó

n formativa: Ventajas, dificultades y satisfacci

ó

n.

Movimento 2016, 22, 1033–1048. [CrossRef]

44.

L

ó

pez-Pastor, V.M.; Monjas, R.; Manrique, J.C.; Barba, J.J.; Gonz

á

lez, M. Assessment implications in

cooperative physical education approaches: The role of formative and shared assessment in the necessary

search for coherence. Cult. Educ. 2008, 20, 457–477. [CrossRef]

45.

Castej

ó

n-Oliva, F.J.; L

ó

pez-Pastor, V.M.; Juli

á

n-Clemente, J.A.; Zaragoza-Casterad, J. Evaluaci

ó

n formativa y

rendimiento acad

é

mico en la formaci

ó

n inicial del profesorado de Educaci

ó

n F

í

sica. Rev. Int. Med. Sci. Act.

Sports 2011, 11, 328–346.

46.

MacPhail, A.; Halbert, J. ‘We had to do intelligent thinking during recent PE’: Students’ and teachers’

experiences of assessment for learning in post-primary physical education. Assess. Educ. Princ. Policy Pract.

2010, 17, 23–39. [CrossRef]

47.

Fisette, J.; Franck, M. How Teachers Can Use PE Metrics for Formative Assessment. J. Phys. Educ. Recreat.

Danc. 2012, 83, 23–34. [CrossRef]

48.

Chr

ó

in

í

n, D.; Cosgrave, C. Implementing formative assessment in primary physical education: Teacher

perspectives and experiences. Phys. Educ. Sports Pedagog. 2013, 18, 219–233. [CrossRef]

49.

Krause, J.; O’Neil, K.; Dauenhauer, B. Plickers: A Formative Assessment Tool for K–12 and PETE Professionals.

Strategies 2017, 30, 30–36. [CrossRef]

50.

Pereira, D.; Flores, M.A.; Niklasson, L. Assessment revisited: A review of research in Assessment and

Evaluation in Higher Education. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2016, 41, 1008–1032. [CrossRef]

51.

Man, A. ‘Formative good, summative bad?’—A review of the dichotomy in assessment literature. J. Furth.

High. Educ. 2016, 40, 509–525. [CrossRef]

52.

Heitink, M.C.; Van der Kleij, F.M.; Veldkamp, B.P.; Schildkamp, K.; Kippers, W.B. A systematic review of

prerequisites for implementing assessment for learning in classroom practice. Educ. Res. Rev.

2016

, 17,

50–62. [CrossRef]

53.

Gerritsen-van Leeuwenkamp, K.; Joosten-ten Brinke, D.; Kester, L. Assessment quality in tertiary education:

An integrative literature review. Stud. Educ. Eval. 2017, 55, 94–116. [CrossRef]

54.

Cocket, A.; Kackson, C. The use of assessment rubrics to enhance feedback in higher education: An integrative

literature review. Nurse Educ. Today 2018, 69, 8–13. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

55.

Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic

reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, 339. [CrossRef]

Sustainability 2020, 12, 9233 14 of 15

56.

Bores-Garc

í

a, D.; Hortigüela-Alcal

á

, D.; Fern

á

ndez-Rio, F.J.; Gonz

á

lez-Calvo, G.; Barba-Mart

í

n, R. Research

on Cooperative Learning in Physical Education. Systematic Review of the Last Five Years. Res. Quart. Exerc.

Sports 2020. [CrossRef]

57.

Barba-Mart

í

n, R.; Bores-Garc

í

a, D.; Hortigüela-Alcal

á

, D.; Gonz

á

lez-Calvo, G. The application of the teaching

games for understanding in physical education. Systematic review of the last six years. Int. J. Environ. Res.

Public Health 2020, 17, 3330. [CrossRef]

58.

Shea, B.; Reeves, B.; Wells, G.; Thuku, M.; Hamel, C.; Moran, J.; Henry, D. AMSTAR 2: A critical appraisal

tool for systematic reviews that include randomized or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions,

or both. BMJ 2017, 358, j4008. [CrossRef]

59.

Moher, D.; Schulz, K.F.; Altman, D. The CONSORT statement: Revised recommendations for improving the

quality of reports of parallel-group randomized trials. JAMA 2001, 285, 1987–1991. [CrossRef]

60.

Downs, S.H.; Black, N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality

both of randomized and non-randomized studies of health care interventions. J. Epidemiol. Community Health

1998, 52, 377–384. [CrossRef]

61.

Von-Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gotzsch, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. The strengthening

the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting

observational studies. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2008, 61, 344–349. [CrossRef]

62.

L

ó

pez-Pastor, V.M.; Barba-Mart

í

n, J.J.; Monjas-Aguado, R.; Manrique-Arribas, J.C.; Heras-Bernardino, C.;

Gonz

á

lez-Pascual, M.; G

ó

mez-Garc

í

a, J.M. Trece años de evaluaci

ó

n compartida en Educaci

ó

n F

í

sica. Rev. Int.

Med. Sci. Phys. Act. Sport 2007, 7, 69–86.

63.

Taras, M. Summative assessment: The missing link for formative assessment. J. Furth. High. Educ.

2009

, 33,

57–69. [CrossRef]

64.

Flynn, S.; Duell, K.; Dehaven, C.; Heidorn, B. Kick, Stroke and Swim: Complement Your Swimming Program

by Engaging the Whole Body on Dry Land and in the Pool. Strategies 2017, 30, 33–38. [CrossRef]

65.

Gikandi, J.W.; Morrow, D.; Davis, N.E. Online formative assessment in higher education: A review of the

literature. Comput. Educ. 2011, 57, 2333–2351. [CrossRef]

66.

Baleni, Z.G. Online Formative Assessment in Higher Education: Its Pros and Cons. Electron. J. e-Learn.

2015

,

13, 228–236.

67.

Yorke, M. Formative assessment in higher education: Moves towards theory and the enhancement of

pedagogic practice. High. Educ. 2003, 45, 477–501. [CrossRef]

68.

Nicol, D.; Macfarlane-Dick, D. Formative assessment and self-regulated learning: A model and seven

principles of good feedback practice. Stud. High. Educ. 2006, 31, 199–218. [CrossRef]

69.

Tempelaar, D. Supporting the less-adaptive student: The role of learning analytics, formative assessment

and blended learning. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2020, 45, 579–593. [CrossRef]

70. Kirk, D. Educación Física y Currículum; Universidad de Valencia: Valencia, Spain, 1990.

71.

Hern

á

ndez, J.L.; Vel

á

zquez, R. La Evaluaci

ó

n en Educaci

ó

n F

í

sica. Investigaci

ó

n y Pr

á

ctica en el

Á

mbito Escolar;

Grao: Barcelona, Spain, 2004.

72.

Rodr

í

guez, J.; Zulaika, L.M. Evaluaci

ó

n en Educaci

ó

n F

í

sica. An

á

lisis comparativo entre la teor

í

a oficial y la

praxis cotidiana. Sport. Sci. J. 2016, 3, 421–438. [CrossRef]

73.

Aarskog, E. ‘No assessment, no learning’ exploring student participation in assessment in Norwegian

physical education (PE). Sports Educ. Soc. 2020. [CrossRef]

74.

Black, P.; Wiliam, D. Developing the theory of formative assessment. Educ. Assess. Eval. Access.

2009

,

21, 5. [CrossRef]

75. Michael, R.; Webster, C. Pickleball Assessment of Skill and Tactics. Strategies 2020, 33, 18–24. [CrossRef]

76. Eather, N.; Riley, N.; Miller, D.; Bradley, J. Evaluating the Effectiveness of Using Peer-Dialogue Assessment

(PDA) for Improving Pre-Service Teachers’ Perceived Confidence and Competence to Teach Physical

Education. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 2017, 42, 69–83. [CrossRef]

77.

Canadas, L.; Castejon, J.; Santos-Pastor, M.L. Relationship between students’ participation in assessment and

grading in physical education teachers’ initial training. Cult. Cienc. Deporte 2018, 13, 290–300. [CrossRef]

78.

L

ó

pez-Pastor, V.M.; P

é

rez-Pueyo,

Á

.; Barba, J.J.; Lorente-Catal

á

n, E. Students’ perceptions of a graduated

scale used for self-assessment and peer-assessment of written work in pre-service physical education teacher

education (PETE). Cult. Cienc. Deporte 2016, 11, 37–50. [CrossRef]

Sustainability 2020, 12, 9233 15 of 15

79.

Macken, S.; MacPhail, A.; Calderon, A. Exploring primary pre-service teachers’ use of ‘assessment for

learning’ while teaching primary physical education during school placement. Phys. Educ. Sports Pedagog.

2020, 25, 539–554. [CrossRef]

80.

Asun-Dieste, S.; Romero-Martin, M.R.; Aparicio-Herguedas, J.L.; Fraile-Aranda, A. Proxemic Behaviour in

Pre-service Teacher Training in Physical Education. Apunts 2020, 141, 41–48. [CrossRef]

81.

Alstot, A. Accuracy of a Peer Process Assessment Performed by Elementary Physical Education Students.

Phys. Educ. 2020, 75, 739–755. [CrossRef]

82.

Soytürk, M. Analysis of Self and Peer Evaluation in Basic Volleyball Skills of Physical Education Teacher

Candidates. J. Educ. Learn. 2019, 8, 256–263. [CrossRef]

83.

Eather, N.; Riley, N.; Miller, D. Evaluating the Impact of Two Dialogical Feedback Methods for Improving

Pre-Service Teacher’s Perceived Confidence and Competence to Teach Physical Education within Authentic

Learning Environments. J. Educ. Train. Stud. 2019, 7, 32–46. [CrossRef]

84.

Martos-Garcia, D.; Usabiaga, O.; Valencia-Peris, A. Students’ Perception on Formative and Shared Assessment:

Connecting two Universities through the Blogosphere. J. New Approaches Educ. Res.

2018

, 6, 64–70. [CrossRef]

85. Denzin, N.K. Critical Qualitative Inquiry. Qual. Inq. 2017, 23, 8–16. [CrossRef]

86.

Fern

á

ndez-Navas, M.; Postigo-Fuentes, A. The situation of qualitative research in Education: Paradigm Wars

again? Márgenes 2020, 1, 45–68.

Publisher’s Note:

MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional

affiliations.

©

2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access

article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution

(CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).