Community

engagement

toolkit for

planning

December 2017

© State of Queensland. First published by the Department of Infrastructure, Local Government and Planning,

1 William Street, Brisbane Qld 4000, Australia, July 2017.

Licence: This work is licensed under the Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 Australia Licence. In essence, you are

free to copy and distribute this material in any format, as long as you attribute the work to the State of

Queensland (Department of Infrastructure, Local Government and Planning) and indicate if any changes have

been made. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Attribution: The State of Queensland, Department of State Development, Manufacturing, Infrastructure and Planning.

The Queensland Government supports and encourages the dissemination and exchange of information. However, copyright protects

this publication. The State of Queensland has no objection to this material being reproduced, made available online or electronically but

only if it is recognised as the owner of the copyright and this material remains unaltered.

The Queensland Government is committed to providing accessible services to Queenslanders of all cultural and linguistic

backgrounds. If you have difficulty understanding this publication and need a translator, please call the Translating and

Interpreting Service (TIS National) on 131 450 and ask them to telephone the Queensland Department State Development,

Manufacturing, Infrastructure and Planning on 13 QGOV (13 74 68).

Disclaimer: While every care has been taken in preparing this publication, the State of Queensland accepts no responsibility for

decisions or actions taken as a result of any data, information, statement or advice, expressed or implied, contained within. To the best

of our knowledge, the content was correct at the time of publishing.

Any references to legislation are not an interpretation of the law. They are to be used as a guide only. The information in this publication

is general and does not take into account individual circumstances or situations. Where appropriate, independent legal advice should be

sought.

An electronic copy of this report is available on the Planning group’s website at https://planning.dilgp.qld.gov.au.

Contents

Preface ......................................................................................................................................... 1

About the toolkit ......................................................................................................................... 2

What is the toolkit? .......................................................................................................... 2

Vision statement ............................................................................................................... 3

Outcomes sought ............................................................................................................. 3

Why is a toolkit needed? ................................................................................................. 3

How the toolkit relates to statutory requirements ......................................................... 3

Part 1: Guiding principles .......................................................................................................... 7

What is community engagement? ................................................................................... 7

What do we mean by ‘community’? ................................................................................ 7

Why is community engagement important?................................................................... 7

Six core principles ........................................................................................................... 9

Resource 1.1: Six core principles ........................................................................................................ 9

International Association for Public Participation ....................................................... 10

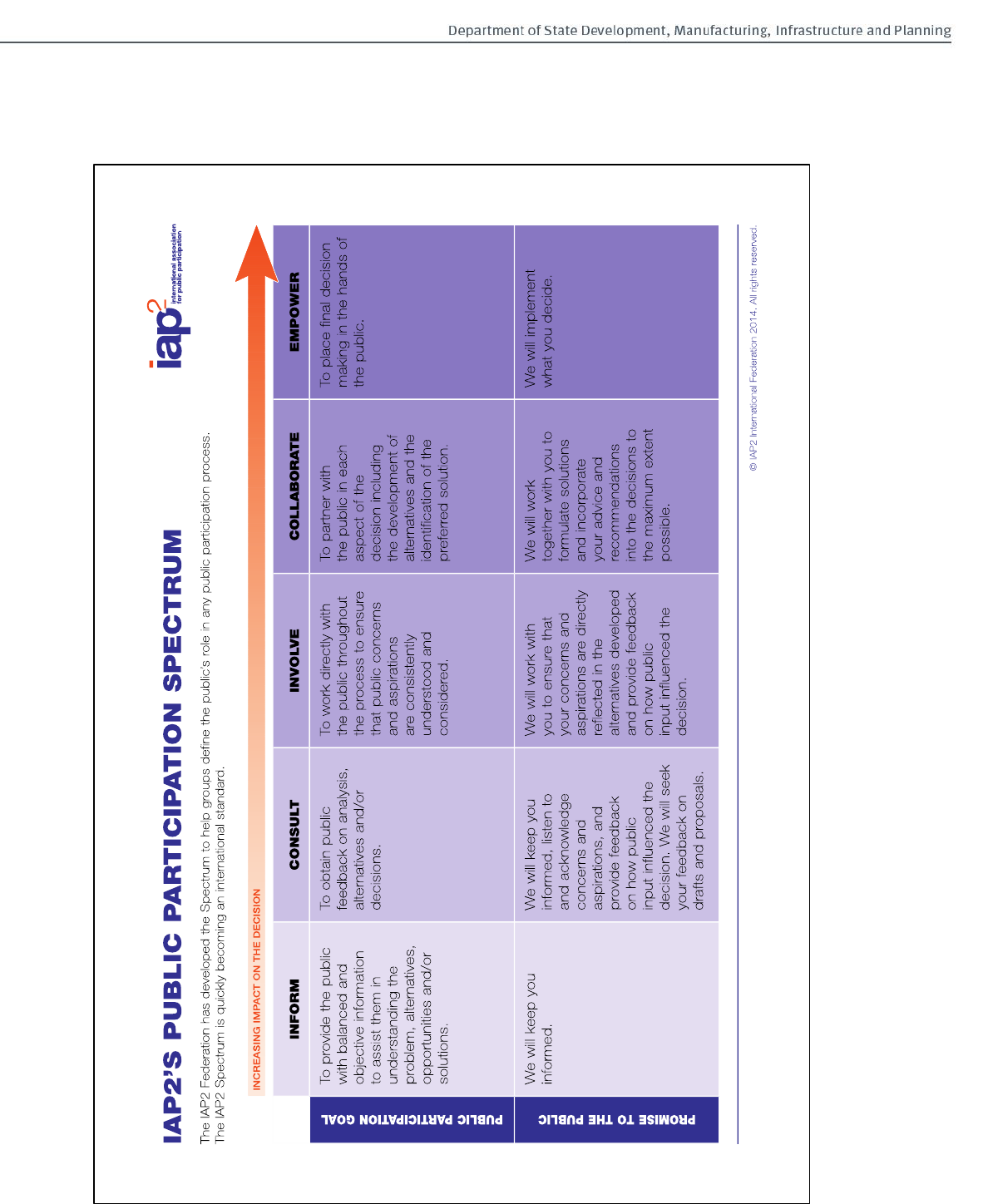

Resource 1.2: IAP2’s public participation spectrum .......................................................................... 11

Part 2: Developing a community engagement plan ................................................................ 13

Tool 2.1: Checklist for developing an engagement plan ................................................................... 13

Define the community engagement scope ................................................................... 14

Tool 2.2A: Aligning community engagement to stakeholder impact levels ....................................... 15

Tool 2.2B: Decision-making flowchart to help align community engagement to stakeholder

impact levels ...................................................................................................................................... 16

Tool 2.3: Listing negotiable and non-negotiable items ...................................................................... 17

Determine the context .................................................................................................... 17

Understand your stakeholders, their interests and levels of influence ...................... 18

Tool 2.4: Stakeholder understanding checklist .................................................................................. 19

Resource 2.1: Stakeholder ability to influence outcomes .................................................................. 20

Tool 2.5: Checklist for identifying stakeholder needs ........................................................................ 21

Tool 2.6: Stakeholder prioritisation table ........................................................................................... 22

Implementation plan....................................................................................................... 23

Tool 2.7: Example community engagement action plan – Local plan for a rural town ...................... 24

Part 3: Selecting community engagement tools ..................................................................... 30

Tool 3.1: Selecting engagement tools to achieve critical success factors for engagement .............. 30

Tool 3.2: Choosing the right engagement tools – options matrix ...................................................... 32

Online engagement ........................................................................................................ 44

Online engagement platforms ....................................................................................... 45

Email marketing .............................................................................................................. 45

Creative ideas: What’s trending in this space? ............................................................ 46

Citizensourcing .................................................................................................................................. 46

Participatory budgeting ...................................................................................................................... 47

Online interactive mapping and priorities .......................................................................................... 47

Mobile applications ............................................................................................................................ 47

Part 4: Engaging with specific groups .................................................................................... 48

Tool 4.1: Overview checklist for engaging with specific groups ........................................................ 48

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities ..................................................... 49

Tool 4.2: Checklist for engaging with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities ................ 50

Resource 4.1: Communicating with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander audiences ...................... 52

Resource 4.2: Closing the gap – Engagement with Indigenous communities in key sectors

(resource sheet no. 23) ...................................................................................................................... 52

Resource 4.3: Know your community – Key insights into Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

Queenslanders................................................................................................................................... 52

Resource 4.4: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’s engagement toolkit ........................... 52

Resource 4.5: Protocols for consultation and negotiation with Aboriginal people and proper

communication with Torres Strait Islander people............................................................................. 52

Older people ................................................................................................................... 53

Tool 4.3: Checklist for engaging with older people ............................................................................ 53

Young people ................................................................................................................. 55

Tool 4.4: Checklist for engaging with young people .......................................................................... 56

People with disability ..................................................................................................... 57

Tool 4.5: Checklist for engaging with people with disability .............................................................. 57

People from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds .................................. 58

Tool 4.6: Checklist for engaging with culturally and linguistically diverse groups ............................. 59

Disadvantaged and homeless people ........................................................................... 60

Tool 4.7: Checklist for engaging with disadvantaged and homeless people ..................................... 60

Part 5: Content development ................................................................................................... 61

Content preparation ....................................................................................................... 61

Tool 5.1: Ten tips for creating suitable content for engagement ....................................................... 61

Tool 5.2: Checklist to guide development of engagement material ................................................... 62

Part 6: Implementing your community engagement strategy ............................................... 64

6.1 Data collection and analysis .................................................................................... 64

Tool 6.1: Checklist for determining data analysis requirements ........................................................ 65

Tool 6.2: Example Excel community engagement database ............................................................ 66

Part 7: Feedback and reporting ............................................................................................... 67

Tool 7.1: Checklist for following up after engagement and preparing a report .................................. 68

Part 8: Evaluation ...................................................................................................................... 69

Tool 8.1: Checklist to guide evaluation of a community engagement process ................................. 69

Part 9: Success stories ............................................................................................................. 71

Tool 9.1: Case study template ........................................................................................................... 71

Case study 9.1: New planning scheme ......................................................................... 71

Case study 9.2: CityShape 2026 .................................................................................... 73

Case study 9.3: Ideas Fiesta .......................................................................................... 75

Case study 9.4 Wet Tropics Plan for People and Country........................................... 77

Case study 9.5: Clifton Township Open Space Concept Master Plan ........................ 80

Part 10: References .................................................................................................................. 83

Community engagement toolkit for planning Page 1 of 89

Preface

Planning creates great places for people to live, work and play. Because of this, local communities

benefit the most from good planning.

Queensland’s planning system encourages effective and genuine community engagement so that local

communities can participate in the planning process. It does this while supporting efficient and

consistent decision-making that instils investment and community confidence.

To encourage genuine community engagement in the planning process, this toolkit has been

developed to help Queensland councils engage with their communities about planning in a meaningful

and open manner. It will be kept up to date by the department, helping all councils to access feedback

on the benefits of engagement tools, as well as current trends in engagement techniques.

We appreciate that many local governments in Queensland have already developed, or are currently

developing, community engagement toolkits. Our goal is to work with these existing toolkits by

providing, and capturing, specific advice about engagement processes and tools that encourage

people to get involved in planning decisions that affect their local community.

The toolkit has been developed with advice from community engagement specialists and their peak

representative body – the International Association of Public Participation (IAP2). IAP2 has endorsed

this toolkit.

The toolkit features easily accessible web-based tools.

Community engagement toolkit for planning Page 2 of 89

About the toolkit

The Queensland Government is responsible for administering the legislation underpinning the state’s

planning and development system. A new era has arrived with the commencement of the Planning Act

2016 and associated new statutory instruments. These form the framework for a better planning system

that enables responsible development and delivers prosperity, sustainability and liveability now and into

the future.

The government is responsible for ensuring that communities can be involved in the decisions about

planning and development that affect them. These decisions relate to planning schemes, other ‘local

planning instruments’

1

and some development decisions where the proposal has been publicly notified.

The state’s role is to:

•

establish overall principles, governance and standards

•

balance and manage the expectations of all stakeholders

•

provide guidance on how to address the principles and meet the standards, while also meeting

community and stakeholder expectations.

What is the toolkit?

This toolkit supports the delivery of effective community engagement in plan-making

throughout Queensland.

It aims to help local governments to develop community engagement strategies for:

• preparing new local planning instruments

• amending existing local planning instruments.

Accordingly, the toolkit is intended to support local governments prepare a communications strategy

under the Minister’s Guidelines and Rules (MGR) for plan-making.

The toolkit is a non-statutory set of practical tools and information intended to support local

governments meet their requirements to engage with the community, as outlined in the MGR. It is also

intended to support community members and stakeholders in their interactions with the plan-making

process.

This toolkit provides a central location for information about current trends in engagement techniques,

the benefits of particular tools when engaging with the community about planning, and case studies. It

does not specifically address community engagement related to the development assessment process

– only those development proposals that are publicly notified provide an opportunity for the community

to have a say. Local governments may still use the tools within the toolkit during the notification

timeframe, but there is not the opportunity to go beyond the statutory time requirements.

1

According to the Planning Act 2016:

A local planning instrument is a planning instrument made by a local government, and is either:

(a) a planning scheme; or

(b) a TLPI [temporary local planning instrument]; or

(c) a planning scheme policy.

Community engagement toolkit for planning Page 3 of 89

The web-based nature of this toolkit provides the capacity for information to be provided in PDF and

other formats, where possible.

Overall, this toolkit aims to foster a new approach to, and enthusiasm for, community engagement for

the benefit of local communities across Queensland. Over time, it will be recognised as the main

repository for leading-practice community engagement in Queensland for the planning system.

Vision statement

Communities in Queensland affected by plan-making processes are able to participate in meaningful,

appropriate and timely community engagement that provides for their views to be considered in a way

commensurate with the scope of the proposed plan or plan-amendment decision.

Outcomes sought

The community is engaged in plan-making in a relevant and appropriate way through:

•

engagement that focuses on the best interests of the community

•

engagement that is open, honest and meaningful

•

engagement approaches that are inclusive and meet their particular needs

•

timely, accurate, easy-to-understand and accessible information

•

transparent decision-making.

The toolkit is not a statutory instrument.

Why is a toolkit needed?

Local communities throughout Queensland are diverse. While local governments, the development

industry and other stakeholders strive to ensure they meet best-practice standards for engagement, the

capacity to research ‘best-practice engagement’ and to conduct community engagement varies widely.

The department believes that:

Queensland’s planning system should support effective and genuine public participation in

planning, whilst providing for efficient and consistent decision-making that instils investment and

community confidence.

2

How the toolkit relates to statutory requirements

Land-use planning is undertaken for a range of reasons including:

•

managing the impacts of growing and diverse populations

•

managing the effects of natural hazards and climate change

•

protecting important resources such as open space, areas of environmental significance and

productive agricultural land.

Planning enables appropriate development in appropriate locations and creates great places for people

to live, work and play. Because of this, local communities are the key beneficiaries of good planning. It

is important to ensure that Queensland’s planning system includes opportunities for genuine and

effective community engagement, and these opportunities need to be secured in the state’s planning

legislation.

2

DILGP, 2015, p. 2.

Community engagement toolkit for planning Page 4 of 89

The MGR shows key points in the process where community engagement needs to be carried out by

local governments for a specified minimum period. These rules also require, in some cases, that local

governments prepare a communications strategy for the new planning scheme or amendment to the

scheme. (See figure 1 below and table 1 on the following page.)

While it is mandatory under the MGR for local governments to develop a communications strategy, the

use of any tools and resources in this toolkit is entirely up to each local government’s discretion. This

toolkit provides a suite of options for local governments to mix and match according to their

circumstances. The state has a role in confirming, or suggesting changes to, the communications

strategy.

The toolkit itself is non-statutory. It provides ideas, options and tools to inform possible approaches to

community engagement.

Figure 1: Relationship with Minister’s Guidelines and Rules

Mandatory

Planning Act 2016

• Minimum timeframes

for public consultation.

• Requirement to set a

communications strategy

Minister’s Guidelines

and Rules (MGR)

• How planning schemes

and other local planning

instruments are made or

changed.

• Communications strategy

must have regard to the

department’s community

engagement toolkit for

planning.

Not mandatory

Community engagement

toolkit

• Could be used for

purposes other than

meeting the MGR

requirements.

• Supports local

governments.

• Available online.

• Kit of tools in one place (it

is not mandatory to use

these tools.)

Community engagement toolkit for planning Page 5 of 89

Table 1: For a communications strategy under chapter 2 of the MGR

Aspect

Community engagement toolkit support

•

A plan for public consultation

complies with any prescribed

consultation period

requirements under the

Planning Act or the relevant

section of the MGR

N/A

•

A statement about the extent

of consultation with relevant

state agencies

Part 2 – Developing a community engagement plan, including:

•

Tool 2.3 – Listing negotiable and non-negotiable items

•

Tool 2.4 – Stakeholder understanding

•

Tool 2.6 – Checklist for identifying stakeholder needs

•

Tool 2.7 – Stakeholder prioritisation table

•

A description of how the

attention of the community, or

the affected part of the

community, will be drawn to

the purpose and general effect

of the instrument

Part 2 - Developing a community engagement plan, including:

•

Tool 2.2A – Aligning community engagement to stakeholder impacts

•

Tool 2.2B – Decision-making flowchart to help align community engagement

to stakeholder impact levels

•

Tool 2.4 – Stakeholder understanding

•

Tool 2.6 – Checklist for identifying stakeholder needs

Part 3 – Selecting community engagement tools:

•

Tool 3.1 – Selecting engagement tools to achieve engagement critical

success factors

•

Tool 3.2 – Choosing the right engagement tools – options matrix

Part 4 – Engaging with specific groups (and the range of checklists and resources

in this part)

For any communications strategy to give consideration to:

•

The proposed geographical

community or communities of

interest to be consulted

Part 1 – Guiding principles: What do we mean by ‘community’?

•

The relevant community

groups, organisations and

stakeholders

Part 2 – Developing a community engagement plan, including:

•

Tool 2.4 – Stakeholder understanding

•

Tool 2.6 – Checklist for identifying stakeholder needs

Part 4 – Engaging with specific groups (and the range of checklists and resources

in this part).

•

How the proposed planning

scheme or amendment is

relevant to the community

Part 2 – Developing a community engagement plan, including:

•

Tool 2.2A – Aligning community engagement to stakeholder impacts

•

Tool 2.2B – Decision-making flowchart to help align community engagement to

stakeholder impact levels

•

The proposed length of

consultation

N/A

•

The proposed methods of

consultation – tools and

activities

Part 3 – Selecting community engagement tools, including:

•

Tool 3.1 – Selecting engagement tools to achieve critical success factors

•

Tool 3.2 – Choosing the right engagement tools

Community engagement toolkit for planning Page 6 of 89

Part 5 – Content development, including:

•

Tool 5.1 – Ten tips for creating engagement content

•

Tool 5.2 – Examples of questions to guide engagement material content

•

Any actions that are optional

or contingent on other actions

occurring in the process

Part 2 – Developing a community engagement plan

Define the community engagement scope

•

The timing of the process,

including any milestones

N/A

•

Any supporting evidence for

the proposed communication

strategy

N/A

Community engagement toolkit for planning Page 7 of 89

Part 1: Guiding principles

What is community engagement?

Different terms are used to describe the concept of community engagement, including public

participation and community consultation. In Australia, the term community engagement tends to be

used more than public participation, with consultation now considered to be a point on the engagement

(or participation) spectrum.

Community engagement, or public participation, has a range of definitions. However, typically it refers

to the process of involving people in the decisions that affect them. Engagement is considered to be

‘the process by which government, organisations, communities and individuals connect in the

development and implementation of decisions that affect them’.

3

What do we mean by ‘community’?

Communities of place

: Where people identify with a defined geographical area, e.g. a council ward, a

housing development or a neighbourhood.

Communities of interest

: Where people share a particular experience, interest or characteristic such

as young people, faith groups, older people, people with disability, migrant groups, community or

sporting groups.

4

Why is community engagement important?

Governments and industry across the globe are increasingly recognising the value of community and

stakeholder engagement as an essential part of project planning and decision-making.

5

Community engagement, in general, enables better outcomes for both the community and government.

It allows the parties involved to identify the concerns, risks, opportunities, options and potential

solutions that surround an issue, leading to more informed decision-making and mutual benefits that

include:

•

better policy development and service delivery

•

a better understanding of the day-to-day experience of people in communities

•

better relationships between the community and the government

•

community awareness and understanding about an issue

•

community buy-in and higher levels of community ownership

•

greater community support for, and more effective, policy implementation

•

determining what will work in reality and what will not

•

a mechanism for feedback/evaluation on existing policies

•

improved communication pathways, such as the use and further development of community

networks

•

opportunity to develop individual and community capacity and shared understanding of both issues

and potential solutions

•

legitimisation of decisions around controversial issues

3

Consult Australia, 2015.

4

City of Tea Tree Gully, 2014

5

IAP2.

Community engagement toolkit for planning Page 8 of 89

•

mutual learning

•

reduced conflict within stakeholder groups because individuals and communities can hear and

understand each other’s points of view, leading to consensus

•

uncovering new ideas and expertise.

In the context of planning, the benefits of community engagement include:

•

better policy decisions when developing local planning instruments

•

a better understanding of the day-to-day experience of people in their communities, and their

appreciation of their local amenity and heritage

•

better relationships between the community and local government

•

community awareness and understanding about the impacts of population growth, natural hazards

and climate change, and the need to protect important resources such as open space, areas of

environmental significance and productive agricultural land

•

community buy-in and higher levels of community ownership of planning instruments

•

a mechanism for feedback and evaluation of planning decisions

•

improved communication between local government and community members

•

opportunity to develop individual and community capacity and shared understanding of potential

planning approaches

•

reduced conflict within stakeholder groups, as individuals and communities can hear and

understand each other’s points of view, leading to consensus

•

uncovering new ideas and expertise.

Communities value the opportunity to meet and discuss issues with each other and with government to

develop innovative solutions, share their experiences, expand their understanding around issues and

develop empathy with competing stakeholders. Creating policy solutions through the engagement

process involves compromises and trade-offs that balance community interest as a whole and enable

budget priorities to be set:

6

… governments cannot help to solve complex problems without the concerted efforts of the

general public. Arriving at solutions will invariably involve trade-offs and outcomes that reflect

and/or balance community interest as a whole and enable budget priorities to be set.

For this reason, governments must engage more broadly with the community and in ways that are

different from what has been tried before.

Accessibility, timing and transparency are all important elements in getting community engagement

right. For complex and controversial issues, undertaking community engagement earlier rather than

later in the life of a policy or project may have major benefits. It gives the community the opportunity to

learn about the trade-offs involved, and a diverse range of community views can be considered in the

development of options or solutions.

In the past, it has been difficult to quantify the benefit of community engagement to projects. In 2015,

Consult Australia, with the support of IAP2, prepared Valuing better engagement: An economic

framework to quantify the value of stakeholder engagement for infrastructure delivery. Although this

document focuses on infrastructure projects, community engagement professionals may find it useful

within the planning framework.

6

Tasmanian Government Framework for Community Engagement, 2013.

Community engagement toolkit for planning Page 9 of 89

Six core principles

The six core principles of community engagement of particular use in the planning framework are

defined below.

Resource 1.1: Six core principles

Community is engaged in a relevant and appropriate way

Principles

How this may be applied at the local level

1. Engagement

focuses on the best

interests of the

community

•

Engagement is undertaken in the best interests of the whole community

(or the affected part of the community, if the changes apply only to part of

the local government area), rather than of any individual person or group.

2. Engagement is

open, honest and

meaningful

•

Engagement draws the attention of the community to all relevant

information, the purpose and general effect of the proposed plan/changes

and the specific details.

•

The community is provided with genuine opportunities to participate

in/contribute to the plan-making process and is kept informed of the

proposed plan/changes and its implications and any amendments during

the process.

3. Approaches to

engagement are

inclusive and

appropriate

•

Engagement is inclusive, appropriate to the needs of the community, and

commensurate with the scale and complexity of the proposed

plan/changes.

•

Reach out to and encourage the community to be involved in discussing

planning and development issues that affect their lives, making sure to

seek out diverse voices and perspectives.

•

Identify and address potential barriers to community input, while being

open with the community about any budget constraints.

•

Consistent engagement processes can make it easier for the community

and stakeholders to participate. However, this must be balanced with the

need for engagement tools to suit the community and the circumstances

of the proposal being considered. Identify approaches to reach all

community members, including those with specific needs (e.g. language,

people with disabilities, older people, and the young). Different

engagement tools and different questions will produce better responses

with different communities. Where possible, use a mix of qualitative and

quantitative engagement methods to gather a diversity of opinions.

4. Information is timely

and relevant

•

The community is provided with information in a timely manner which

allows for input before decisions are made.

•

Sufficient time is allowed for the community to consider information and

then make a meaningful contribution to the plan-making or development

assessment process.

•

Engagement should start early in the plan-making or development process

when objectives and options are being identified.

•

Listening to the community, addressing their concerns, and building

capacity to understand planning and development issues and solutions

can mean longer periods of engagement.

•

Recognise that public engagement is a dynamic, ongoing process that

requires flexibility.

Community engagement toolkit for planning Page 10 of 89

5. Information is

accurate, easy to

understand and

accessible

The community has easy access to information that is:

•

accurate, easy to read and easy to understand

•

tailored to the community, where necessary, in language and style

•

in a form that appeals to the intended audience

•

clear about how to make a submission, how the submission will be dealt

with, and the general timeframe before a decision can be expected.

6. Decision-making is

transparent

•

The final decision about the proposed plan, changes to the plan or the

development proposal is made in an open and transparent way.

•

The community, as a whole, and individual submitters are provided with

reasons for the decision and information about how all submissions have

been taken into account.

International Association for Public Participation

The International Association for Public Participation (IAP2) Federation and Australasian chapter offers

concepts, principles and current industry practice in relation to community engagement. IAP2 defines

community engagement as:

Any process that involves the community in problem-solving or decision-making and uses

community input to make better decisions.

IAP2 has developed seven core values for the practice of public participation:

…for use in developing and implementing public participation processes to help inform better

decisions that reflect the interests and concerns of potentially affected people and entities’.

These core values are:

1. Public participation is based on the belief that those who are affected by a decision have a right to

be involved in the decision-making process.

2. Public participation includes the promise that the public’s contribution will influence the decision.

3. Public participation promotes sustainable decisions by recognising and communicating the needs

and interests of all participants, including decision makers.

4. Public participation seeks out and facilitates the involvement of those potentially affected by or

interested in a decision.

5. Public participation seeks input from participants in designing how they participate.

6. Public participation provides participants with the information they need to participate in a

meaningful way.

7. Public participation communicates to participants how their input affected the decision.

In addition, the IAP2 Quality Assurance Standard for Community and Stakeholder Engagement outlines

steps for implementing quality engagement. It includes a process that audits an engagement process

against the IAP2 core values.

IAP2 developed a spectrum of public participation that helps define the community’s role in any

community engagement process. The IAP2 Spectrum (2014)

shows that differing levels of participation

are appropriate, depending on the outcomes, timeframes, resources and levels of concern or interest in

the decision to be made. Most importantly, the spectrum sets out the promise being made to the public

at each participation level.

The IAP2 Spectrum is referenced in some form, or underpins, many local and state government

community engagement toolkits available in Australia.

Community engagement toolkit for planning Page 11 of 89

Resource 1.2: IAP2’s public participation spectrum

Community engagement toolkit for planning Page 12 of 89

In 2014, IAP2 Australasia developed a community engagement model that identified seven key drivers

of contemporary engagement. These are:

1. community connectedness

2. greater access to information

3. increased visibility

4. pressure to deliver value for money

5. the nature of complex problems

6. commercial pressure to innovate

7. mobility and pace of communication.

This contemporary engagement model recognises that engagement activities may be led by the

organisation, the community or both. It also recognises that the action may be driven by the community,

the organisation or both.

In the context of the planning system, the prevalent model would be where a local government or a

developer both leads the process and takes action. There may also be some current examples of

where local governments and their communities have shared leadership and action. In the future, it is

likely that there will be more examples of planning projects where the community advocates for change

and local government acts accordingly.

Figure 2: Community-engagement models

Source: IAP2 Australasia. IAP2 Australasia Contemporary Engagement Model

Community engagement toolkit for planning Page 13 of 89

Part 2: Developing a community engagement plan

A community engagement plan should outline a clear approach to how the community and

stakeholders will be engaged on planning and development matters. To respond to the circumstances

of a particular local government or a particular community, engagement plans can take many different

forms. However, they should, at least, address the matters listed in the following checklist.

Tool 2.1: Checklist for developing an engagement plan

Engagement purpose

: Have you clearly defined the purpose of the engagement?

This involves explaining the reason input or participation is necessary, i.e. what planning

problem is the community helping to resolve or what decision does local government need

to make? This process also involves defining the stakeholders affected and the decision-

makers.

Engagement scope

: Have you clearly defined the scope of the engagement project?

This involves explaining the decisions that need to be made, what the engagement

process will focus on, and what you are seeking input on. This process also involves

defining what is non-negotiable (i.e. what the community cannot influence) and what is

negotiable (i.e. what the community can influence). At this point you could also reach out to

internal engagement staff to confirm your approach, and determine if external engagement

resources are required.

Engagement objectives

: Have you clearly defined the objectives that the engagement

process will achieve?

This involves explaining the objectives of your engagement process. Engagement

objectives could relate to a range of potential outcomes, including:

building community capacity to understand planning and development issues

building stronger relationships with community and stakeholders

seeking innovative solutions for planning and development challenges

making better decisions about planning and development.

Context analysis

: Have you conducted analysis to understand the local, regional, state

and national context that will affect the engagement process?

This could involve exploring local demographic and economic characteristics, access to

technology, level of understanding of planning issues, response to previous engagement

processes.

Stakeholder and issues analysis

: Have you conducted analysis of the different

stakeholders and community groups that could be interested in your process?

This analysis could include identifying stakeholders and community groups, exploring what

issues are of interest to them and how these individuals and groups might be affected, and

what methods you will use to engage and build relationships with them.

Level of engagement

: Have you determined the role of the community in the decision-

making process?

This process involves determining whether you will be promising to inform, consult,

involve, collaborate or empower the community. This could also include identifying the

phases of a project or process where the particular levels of engagement will apply.

Engagement phases

: Have you described the project phases and timeframes?

This involves describing the phases of your project, and the associated timeframes, and

Community engagement toolkit for planning Page 14 of 89

how the engagement process supports these phases and complements the overall delivery

of the project.

Data collection and analysis

: Have you determined what data are required to support the

decision?

This process involves identifying how community input will be collected and in what format,

and how it will be used to inform the decision.

Engagement methods

: Have you defined a list of methods or tools you will use to inform

community members, and gain community input, feedback or collaboration to achieve your

engagement objectives?

This will include communication methods to raise awareness or understanding about the

planning or development project, and how feedback will be provided to the community

about the engagement process, what has been heard and how it will be considered.

Resources

: Determine what financial and human resources are needed, or are available,

to deliver the defined engagement methods.

Implementation plan

: Define a schedule for how and when the engagement will occur,

which should be linked to the engagement phases of the project.

Feedback

: Identify how feedback will be provided to community members and

stakeholders so that they understand how their input shaped the project or process

outcome.

Evaluation measures

: Define what you will do to evaluate the success of your

engagement. This could include ways to measure how satisfied the community and the

project team are with the engagement process, the quality of the input received, and how

well the engagement program achieved your stated objectives.

Define the community engagement scope

As a first step, you will need to scope the engagement project and determine what level of community

engagement is appropriate. This step will help to clarify why you are engaging with the community

(i.e. the purpose) and to identify community engagement objectives relevant to your project. This step

addresses the first three items on the checklist.

Community engagement objectives describe what needs to be achieved with your stakeholders in the

delivery of your engagement project. Some of the objectives will be about actions or activities and

some will be about the relationships with stakeholders.

The work by the Social Planning and Research Council of British Columbia to develop four levels of

impact and associated criteria can help you assess the likely level of impact that the planning or

development project may have on the community and stakeholders. Applying this to the IAP2 Public

Participation Spectrum provides further guidance in understanding the relationship between the level of

community impact and the level of engagement that should be applied.

Community engagement toolkit for planning Page 15 of 89

Tool 2.2A: Aligning community engagement to stakeholder impact levels

Likely level of impact

Criteria

Examples

Level of

community

engagement

High impact on whole

community

•

High impact across

community including to

the natural environment

or general health and

safety of all residents.

•

High degree of interest

across the community.

•

Strong possibility of

conflicting perspectives.

•

New planning scheme

for the whole local

government area.

Involve/

collaborate

High impact on a select

area and/or community

group

•

High impact on a

specific neighbourhood,

group in the community

or specific service or

program.

•

Strong possibility of

conflicting perspectives

at the neighbourhood

level or the need for

trade-offs among

certain groups.

•

Changes in zoning to

restrict future

development rights.

•

Increases in density in

key locations.

•

New or amendments to

existing, neighbourhood

or local plan.

Modest impact on whole

community

•

Modest impact across

the community.

•

Sufficient degree of

interest to warrant

community

engagement.

•

Moderate possibility for

conflicting perspectives.

•

Updating planning

scheme provisions

relating to small-lot

housing or apartment

building design.

•

The inclusion of a new

flood overlay.

Consult

Modest impact on select

area and/or community

group

•

Modest impact on a

neighbourhood area,

community group(s) or

specific facility/service.

•

Small change to a

localised facility/service.

•

Modest risk of

controversy or conflict

at the local level.

•

Changes to hours of

operation of a

community facility.

•

Intersection redesign.

Inform

Community engagement toolkit for planning Page 16 of 89

Tool 2.2B: Decision-making flowchart to help align community engagement to stakeholder

impact levels

This tool can be used in conjunction with 2.2A to help you align impact levels with level of community

engagement. Once you have identified a level of community engagement you can refer to

Resource 1.2: IAP2’s public participation spectrum to determine associated goal and promise to the

community.

For planning projects, some decisions may be non-negotiable, while others may be negotiable.

Defining what is negotiable and what is not will determine how you engage with your community and

stakeholders. It is important to understand what these negotiables and non-negotiables are at the start

of a project or process in order to manage community and stakeholder expectations about their level of

influence on project or process outcomes.

Impact level

High impact on

whole community

Involve/collaborate

High impact on

select area/group

Involve/collaborate

Modest impact on

whole community

Consult

Modest impact on

select area/group

Inform

Community engagement toolkit for planning Page 17 of 89

Tool 2.3: Listing negotiable and non-negotiable items

Please note that this tool only lists some examples for illustration purposes. You will need to add to the

table your project’s circumstances.

Non-negotiable

Negotiable

Non-negotiable items are the elements of a

planning process or project that cannot

change. Some examples are listed below.

Each project is different. It pays to consider

this question up-front on every project:

What aspect of this project cannot change?

What is fixed?

Negotiable items are those that are not bound

by legislative or statutory requirements. Some

examples are listed below. Each project is

different. It pays to consider this question up-

front on every project:

What aspects of this project can be influenced

by the community and stakeholders?

For example, legislative requirements for

engagement that needs to be followed.

For example, the range of engagement

techniques that can be implemented to add

value to the statutory process.

For example, the amount of budget local

government has allocated to spend on the

engagement process.

For example, the opportunity to work with the

community to implement community-led and

community-funded engagement activities.

For example, community safety such as the

need to restrict development in flood-prone

areas.

For example, the opportunity to influence how

density is addressed in a local government

area.

For example, the need to protect certain flora

and fauna communities because they are

listed as ‘rare and threatened’.

For example, the opportunity to influence

where parkland is located, or its function, in a

local government area.

Determine the context

An important step when planning any community engagement is to familiarise yourself with any existing

plans or reports related to your planning project, your stakeholders and community members, or the

local area. Whether recent or historical, they will offer valuable insights into community and stakeholder

sentiments, key issues and areas of interest that may be relevant to your planning project. Some

examples are:

•

demographic and economic information, including population projections or analysis of community

characteristics (e.g. age, ethnicity, socio-economic indicators)

•

reports about environmental constraints affecting the area (e.g. flooding, vegetation and landslip)

•

reports about local character and streetscape

•

traffic information, and future and historic infrastructure plans

•

previous community engagement outcomes for similar projects, locations or demographics.

Community engagement toolkit for planning Page 18 of 89

Understand your stakeholders, their

interests and levels of influence

Not all stakeholders in a particular group or sub-group will necessarily share the same concerns or

have unified opinions or priorities. This step explores how to understand and identify stakeholders who

should be involved in the engagement process.

Identification of key stakeholders is vital to engaging with people in the community who can contribute,

or can influence and encourage others to contribute.

Satisfaction with local government is not confined to roads, rates, safety and rubbish. Sometimes

improvements in these areas may not measurably improve overall community satisfaction. If a local

government wants to improve community perceptions, it is critical that they seek to understand what

makes its residents ‘tick’.

7

Every stakeholder or community group has their own reason to participate in an engagement process.

An understanding of these motives is good to keep in mind, e.g. young people may want to show their

capabilities and older people may want to share their expertise.

8

Three key steps can be taken to better understand your stakeholders.

7

Bang the Table: http://bangthetable.com/2011/07/02/all-lgas-are-unique-arent-they/

8

Citzenlab: http://citizenlab.co/blog/civic-engagement/3-key-learnings-to-move-forward-with-citizen-engagement-co-

creation/?utm_source=CitizenLab+Newsletter&utm_campaign=d0047db73a-

CitizenLab_s_Weekly5&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_459e3f49da-d0047db73a-142562401

Community engagement toolkit for planning Page 19 of 89

Tool 2.4: Stakeholder understanding checklist

Step 1: Identify stakeholders

Have you considered who the stakeholders are? Have you identified the individuals and

groups that will be affected by the outcomes of the planning process? Have you identified

the individuals or groups that may be able to influence the outcomes of a planning

process?

A stakeholder is someone who can affect the success of the planning project or who will

be affected by the project.

Larger projects are likely to have a larger number of stakeholders involved. However, do

not underestimate the number of people that could become interested or involved in

smaller projects.

Your list of stakeholders should be as exhaustive as possible. This is the time to make

sure that you understand the local and regional contexts of your project, the people who

help to shape those contexts, and what planning issues interest them.

Do you understand the demographic characteristics of your community, and any socio-

economic indicators? Do you know whether the community understands planning issues?

How have they responded to previous engagement processes?

For each stakeholder, it is important to understand how they might be affected, what their

level of interest is likely to be, and what their level of interest should be (particularly where

the planning outcomes may create long-term changes that are not easily understood

impacts, e.g. changes in density in a residential area).

Step 2: Analyse stakeholder influence and impact

Once you have identified the stakeholders, and captured information about their influence,

interest and levels of understanding about planning issues, you can start to analyse this

information.

How much constructive or negative influence could a stakeholder have on the outcomes of

the planning process? How much interest are they likely to have?

This step involves analysing each of your identified stakeholders against certain criteria.

The two key criteria to analyse stakeholders against are:

1) extent to which they are interested (low to high)

2) ability to influence outcomes (low to high).

Once this analysis is complete, you will be able to create a prioritised list of stakeholders

and an associated engagement strategy.

Step 3: Prioritise stakeholders

Have you completed your analysis of stakeholder interest and influence? If so, you can now

prioritise your key stakeholder list.

Does your stakeholder have a low level of interest and low level of influence? Then they

may be a lower priority for your engagement strategy.

Should the stakeholder be more interested than they are? If this is the case, consider

treating them as if their interest is high, so that you can raise awareness and generate their

interest.

Does your stakeholder have a high level of interest and high influence? Then they will have

a higher priority in your engagement strategy.

Community engagement toolkit for planning Page 20 of 89

This exercise should be conducted for all your identified stakeholders, so that your engagement

strategy can comprehensively address all stakeholder interests.

Resource 2.1: Stakeholder ability to influence outcomes

It is important to note that this toolkit does not focus on the 'empower' end of the IAP2 Spectrum. The

goal of processes that empower is to place decision-making in the hands of the community. With the

purpose of the toolkit in mind, this would mean that local governments would commit to implementing

what the community decided in relation to planning processes, rather than make that decision

themselves. However, in practice, during the plan-making or amendment process, it is necessary for

local governments to weigh up a range of factors such as environment, economy, employment,

transport and housing. Many of these factors have legislative requirements that need to be complied

with.

Community engagement toolkit for planning Page 21 of 89

Tool 2.5: Checklist for identifying stakeholder needs

This tool will help you to identify the different needs of stakeholders, as they become involved in your

engagement process.

What level of information do stakeholders need to make an informed decision about the

planning project? Do they already understand planning concepts? Do they need support to

build their understanding of planning concepts?

What level of information are stakeholders likely to seek about your project?

Will all stakeholder contributions influence the project equally? Or are there some

individuals or groups that will have more influence on the outcomes of the project?

Remember that it is important to be transparent.

Is a community leader available to assist with the community engagement process? Will

this community leader be able to make introductions? Will the assistance of this

community leader build the credibility of the project or the project team?

Will everyone interested in, or potentially affected by, the project have an opportunity to

become involved?

Have efforts been made to include under-represented community groups in all community

engagement processes (e.g. younger people, older people, people with disabilities,

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, people from culturally and linguistically

diverse backgrounds, and disadvantaged and homeless people)?

Are there any barriers that may prevent some stakeholders from participating in the

process? These barriers could be physical, economic, cultural, or linguistic.

Community engagement toolkit for planning Page 22 of 89

Tool 2.6: Stakeholder prioritisation table

Stakeholder

name

Contact person

Impact

(L, M, H)

Influence

(L, M, H)

What is important to the

stakeholder

How might the stakeholder

contribute to the project?

How might the stakeholder

oppose the project?

Strategy for engaging the

stakeholder

What is the

name of the

stakeholder

group or

individual?

Who is the

nominated contact

person?

Will the impact

of the project on

the stakeholder

be low, medium

or high?

Tools 2.2A,

2.2B, 2.4 and

2.6 will help you

to understand

the impact.

Will the potential

influence of the

stakeholder on

the project’s

outcome be low,

medium or high?

What is important to this

stakeholder? What do they value?

What do they comment on in the

media? What are their

submissions usually about?

How could the stakeholder

contribute to the project, either

constructively or negatively? Do

they have resources that might be

useful to you? Can they introduce

you to other stakeholders?

What actions could the

stakeholder take to oppose the

project? What statements could

they make to influence others to

oppose the project?

What approach will you take to

engage with this stakeholder? Are

you informing, consulting,

involving or collaborating with

them? Or are you empowering

them to make a decision? What

techniques will you implement to

engage with this stakeholder?

Resource 2.1 will help you to

determine the level of engagement

that may be required.

For example:

Our Town’s

Koala Action

Group

Mr John Smith

L

H

This group is very interested in

protecting koalas and koala

habitat.

Their comments in the media

typically relate to the impact that

development has on koala habitat,

and associated impact on the

species.

Any submissions they make

generally focus on koalas but often

mention broader aspects of

environmental protection as well

and the adverse effects of

development.

This group has commissioned

research about koalas in our local

government area. They could be

happy to share their data.

Highly motivated group with large

membership.

Members make submissions on

planning projects and have been

known to protest at sites where

vegetation is being cleared.

Mr John Smith is often quoted in

print and online media and

interviewed for radio and TV. His

statements are often provocative.

For this project, we need to

proactively involve this group, as

they have knowledge to share that

can help the strategic planning

process.

Techniques will include:

•

meetings with Mr John Smith

and a small number of

members involve

representatives in any

workshops that focus on

environmental management

•

include a representative on the

Community Reference Group

established for the project.

For example:

Mrs Stephanie

Jones

H

M

This local resident will be directly

affected by the proposed increase

in density in this neighbourhood.

Mrs Jones has made statements

in the past about the negative

impacts of increased density on

her amenity.

Mrs Jones has made submissions

in the past, and written letters to

the editor.

There is an opportunity here to

build Mrs Jones’ understanding of

planning concepts, particularly the

trade-offs required if development

in this area remains low density.

It is very likely that Mrs Jones will

create an action group to oppose

this project, if she does not feel

that she has been listened to.

It is important that we consult with

Mrs Jones as part of this

engagement process.

Techniques will include:

•

one-on-one interviews

•

direct invitations to community

events

•

telephone contact.

Community engagement toolkit for planning Page 23 of 89

Implementation plan

The implementation plan is a crucial step in the community engagement process. This

plan lists the engagement tools for each phase of the project or process. It also includes

the resources required to deliver the tools and the timeframes that they need to be

delivered in.

This step depends on selecting the right tools for the community engagement process.

Selecting community engagement tools is described in more detail in part 3 of this

toolkit.

The following community engagement action plan is an example only and has been

created for an imaginary rural town in Queensland, with a population of between 6000

and 10,000 people.

In developing this action plan, these assumptions have been made:

•

The local plan being prepared is a medium to long-term plan that identifies the

needs and aspirations of the local community and outlines the actions that need to

be taken to achieve these local planning goals.

•

Resources are available in-house to deliver all the engagement tasks outlined in the

action plan, and specific skills may need to be supplemented by outsourcing.

The example community engagement includes a range of traditional and contemporary

tools to reflect the breadth of tools outlined in part 3, specifically tool 3.2.

The timeframes outlined in a community engagement action plan would need to coincide

with the timeframes for the development of the local plan. Given that the following action

plan is an example only, timeframes have not been specified.

Community engagement toolkit for planning Page 24 of 89

Tool 2.7: Example community engagement action plan – Local plan for a rural town

Activity

Description

Stakeholder group

Actions

Resources and

budget

Timeframes

Responsible

officer

Phase 1: Raise awareness (timing depends on overall program to develop local plan)

Letters to ratepayers

Prepare a letter that outlines

the project and why it is

needed, and outlines the

engagement process.

Distribute the letter to all

ratepayers.

Broader community

•

Prepare letter

•

Distribute

•

In-house writer

•

Postal costs

•

Prepare

•

Approvals

•

Distribute

Name of individual

tasked to

complete action

Advertisements

Place advertisements in local

newspaper and book

community service

announcements.

Broader community

•

Prepare

advertisement

•

Book advertisements

•

In-house writer

•

Advertising

costs

•

Prepare

•

Approvals

•

Distribute

Name of individual

tasked to

complete action

Establish webpage

Establish a page for the

project on council’s current

website. Prepare

background information and

FAQs for page. Provide

more detail to support

information supplied in letter

to ratepayers.

Broader community

•

Prepare webpage

•

Prepare content for

webpage

•

Go live

•

In-house writer

•

Graphic

designer

•

In-house web

team

•

Prepare

•

Approvals

•

Go live

•

Ongoing updates

throughout project

Name of individual

tasked to

complete action

Media release

Prepare and issue a media

release for the local paper to

raise awareness of project.

Broader community

•

Prepare release

•

Approve release

•

Issue

•

In-house team

member

•

Prepare

•

Approvals

•

Issue

•

Ongoing throughout

project to promote

events

Name of individual

tasked to

complete action

Email address

Project hotline

Create a project email

address and project

telephone hotline.

Broader community

•

Create email

address

•

Create phone

number

In-house team

member

•

Prepare

•

Go live

Name of individual

tasked to

complete action

Facebook and

Establish Facebook page

Broader community

•

Create Facebook

In-house team

•

Prepare

Name of individual

Community engagement toolkit for planning Page 25 of 89

Activity

Description

Stakeholder group

Actions

Resources and

budget

Timeframes

Responsible

officer

Instagram

and Instagram account.

Create a hashtag #mytown.

page

•

Create Instagram

account

member

•

Go live

•

Ongoing posts to

promote project and

create community

interest.

tasked to

complete action

Community and local

radio

Establish a regular interview

with a planner to discuss

planning concepts.

Broader community

•

Pitch story ideas

about the project to

local radio and

community radio.

•

Establish regular

radio spots.

•

In-house team

member

•

Prepare

•

First interview

Name of individual

tasked to

complete action

Interviewee

Direct email

Send direct emails to

representatives of identified

stakeholder groups. Email

will outline the project, why it

is needed, and the

engagement process.

Identified stakeholder

groups

•

Prepare and send

email.

•

In-house team

member

•

Prepare

•

Approve

•

Distribute

Name of individual

tasked to

complete action

Community Reference

Group

Establish and meet with

Community Reference

Group.

Focus of first meeting will be

on outlining the project, why

it is needed, and the

engagement process.

Identified stakeholder

groups

•

Identify stakeholder

groups that could

contribute to

Community

Reference Group.

•

Develop terms of

reference for the

group.

•

Issue invitations and

conduct first

meeting.

•

In-house team

member

•

Catering and

venue hire

•

Staff costs to

attend meeting

•

Facilitator

costs

•

Identify groups

•

Prepare terms of

reference

•

Approvals

•

Invitations

•

Conduct meeting

Name of individual

tasked to

complete actions

Name of planning

staff required to

attend meeting

Community engagement toolkit for planning Page 26 of 89

Activity

Description

Stakeholder group

Actions

Resources and

budget

Timeframes

Responsible

officer

Phase 2: Capturing community input for draft local plan (timing dependent on overall program to develop local plan)

Prepare print materials

to support Phase 2

engagement

Print materials could include

flyers, factsheets, and

brochures.

Broader community

•

Prepare materials.

•

Print materials.

•

In-house team

member

•

Printing costs

Distribution costs

•

Prepare materials

•

Print materials

•

Distribute

Name of individual

tasked to

complete action

Main Street ‘Talk to a

Planner’ sessions

Conduct regular drop-in

sessions in the main street

where community members

can talk to a planner about

the future of the town and

the planning concepts that

are being considered as part

of the planning process.

Identify other opportunities

for Talk to a Planner

sessions, e.g. local show,

farmers markets etc.

Capture conversations in

database.

Broader community

•

Prepare materials.

•

Book space.

•

Establish equipment

kit.

•

In-house team

member to

arrange

sessions

•

Equipment

costs

•

Staff costs to

attend

sessions

•

Prepare and promote a

monthly session

throughout this phase of

project

•

Ad-hoc sessions as

needed

Name of individual

tasked to

complete action

Name of staff and

which session

attending

Instagram campaign

Launch Instagram campaign

#mytown to encourage

people to share images of

the things that are important

to them in town.

Broader community

(particularly younger

demographic)

•

Promote #mytown

campaign.

•

Track images

posted.

•

Share images with

team and capture in

database.

•

In-house team

member

•

Ongoing throughout

phase

Name of individual

tasked to

complete action

Community engagement toolkit for planning Page 27 of 89

Activity

Description

Stakeholder group

Actions

Resources and

budget

Timeframes

Responsible

officer

Community workshop

Conduct workshop with

interested community

members and invited

stakeholders.

Explore range of planning

topics that are being

considered as part of the

local plan.

Broader community

Identified

stakeholders

•

Prepare and

promote.

•

Conduct workshop.

•

In-house team

member to

prepare and

promote

•

Staff costs to

attend

•

Venue and

catering costs

•

Facilitator

costs

•

Prepare and promote

•

Conduct workshop

Name of individual

tasked to

complete action

Conversation Toolkit

Prepare conversation toolkit

to encourage broader

community to discuss the

project and planning

concepts, at home, work,

school, or community group

meetings.

Toolkit includes a hard-copy

survey.

Broader community

•

Prepare and

promote.

•

Make available on

the webpage.

•

In-house team

member to

promote

•

Consultant

costs to

prepare

•

Prepare and promote

•

Launch

Name of individual

tasked to

complete action

Online survey

Make Conversation Toolkit

survey available online.

Promote availability.

Broader community

•

Prepare and

promote.

•

Make available on

the webpage.

•

In-house team

member

•

Prepare and promote

•

Launch

Name of individual

tasked to

complete action

Community Reference

Group

Meet with Community

Reference Group.

Focus of meeting is to

discuss planning challenges,

community feedback and to

input into planning process.

Identified stakeholder

groups

•

Conduct meetings.

•

In-house team

member

•

Catering and

venue hire

•

Staff costs to

attend meeting

•

Facilitator

costs

•

Three meetings

throughout this phase, or

as needed

Name of individual

tasked to

complete actions

Name of planning

staff required to

attend meeting

Community engagement toolkit for planning Page 28 of 89

Activity

Description

Stakeholder group

Actions

Resources and

budget

Timeframes

Responsible

officer

Phase 3: Public Notice period (tasks described here are additional to those outlined in the Minister’s Guidelines and Rules) (timing dependent on overall program to develop

local plan)

Prepare print materials

to support Phase 3

engagement

Print materials could include

fact sheets (including one

that shows how community

and stakeholder input has

shaped plan), brochure, and

guide to making a ‘properly

made submission’.

Broader community

•

Prepare materials.

•

Print materials.

•

In-house team

member

•

Printing costs

•

Distribution

costs

•

Prepare materials

•

Print

•

Distribute

Name of individual

tasked to

complete action

Community Reference

Group

Meet with Community

Reference Group.

Focus of meeting is to

discuss draft plan.

Identified stakeholder

groups

•

Conduct meeting

•

In-house team

member

•

Catering and

venue hire

•

Staff costs to

attend meeting

•