Australian Competition and Consumer Commission

23 Marcus Clarke Street, Canberra, Australian Capital Territory, 2601

© Commonwealth of Australia 2021

This work is copyright. In addition to any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, all material contained within this work is provided

under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence, with the exception of:

the Commonwealth Coat of Arms

the ACCC and AER logos

any illustration, diagram, photograph or graphic over which the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission does not hold

copyright, but which may be part of or contained within this publication.

The details of the relevant licence conditions are available on the Creative Commons website, as is the full legal code for the CC BY 3.0 AU

licence.

Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the Director, Content and Digital Services, ACCC,

GPOBox 3131, Canberra ACT 2601.

Important notice

The information in this publication is for general guidance only. It does not constitute legal or other professional advice, and should not be

relied on as a statement of the law in any jurisdiction. Because it is intended only as a general guide, it may contain generalisations. You

should obtain professional advice if you have any specific concern.

The ACCC has made every reasonable eort to provide current and accurate information, but it does not make any guarantees regarding

the accuracy, currency or completeness of that information.

Parties who wish to re-publish or otherwise use the information in this publication must check this information for currency and accuracy

prior to publication. This should be done prior to each publication edition, as ACCC guidance and relevant transitional legislation

frequently change. Any queries parties have should be addressed to the Director, Content and Digital Services, ACCC, GPO Box 3131,

Canberra ACT 2601.

ACCC 03/21_21–15

www.accc.gov.au

1

Contents

Executive Summary .............................................................................................................. 3

App marketplaces are critical gateways to reach consumers.......................................... 3

Apple and Google’s market power in app marketplaces and the link to their mobile

operating systems .......................................................................................................... 4

App developer concerns with the operation of the dominant app marketplaces .............. 5

Harmful apps and consumer complaints handling ........................................................ 10

Overseas developments and the importance of international cooperation .................... 12

Measures to address competition and consumer issues in app marketplaces .............. 13

Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 15

1. Overview of mobile apps and app marketplaces .......................................................... 16

1.1. The rise of smartphones and apps in Australia ..................................................... 16

1.2. Mobile operating systems and app marketplaces .................................................. 19

1.3. Benefits of app marketplaces for consumers and app developers ......................... 21

2. Competition Assessment .............................................................................................. 23

2.1. Scope of ACCC’s competition assessment ........................................................... 24

2.2. Mobile operating systems, apps and app marketplaces ........................................ 24

2.3. Competitive constraints on the Play Store ............................................................. 33

2.4. Competitive constraints on the App Store ............................................................. 41

2.5. Market power in mobile app distribution ................................................................ 43

3. Apple and Google’s terms and conditions which govern access to their respective

marketplaces ...................................................................................................................... 44

3.1. Terms and conditions of app marketplaces ........................................................... 45

3.2. The app review process ........................................................................................ 48

3.3. Access to device and operating system functionality drives innovation and

consumer choice in downstream markets for apps ....................................................... 57

4. Terms relating to app payments ................................................................................... 63

4.1. Setting the scene .................................................................................................. 64

4.2. The application and enforcement of Apple and Google’s IAP requirements .......... 68

4.3. Restrictions on informing consumers about alternative payment options outside an

app ............................................................................................................................. 79

5. Discovery and display of apps ...................................................................................... 84

5.1. Consumers’ discovery of apps in the App Store and Play Store ............................ 85

2

5.2. There is a lack of transparency for app developers regarding the operation of

search .......................................................................................................................... 87

5.3. Greater discovery opportunities for certain apps on the App Store’s search and

editorials....................................................................................................................... 92

5.4. Pre-installation of apps and default settings ........................................................ 101

6. Harms through malicious apps and complaints handling ............................................ 108

6.1. Harmful, malicious and exploitative apps on app marketplaces........................... 109

6.2. Consumer detriment attributable to apps ............................................................ 114

6.3. Other potential measures to address harmful, malicious and exploitative apps ... 121

6.4. Complaints handling processes .......................................................................... 122

7. Data practices ............................................................................................................ 127

7.1. Data practices impacting competition .................................................................. 129

7.2. Data practices impacting consumers .................................................................. 136

Glossary............................................................................................................................ 148

Appendix A: Ministerial direction ....................................................................................... 153

Appendix B: Apps that come pre-installed on iOS and Android devices ............................ 162

3

Executive Summary

This second interim report (Report) under the five-year Digital Platform Services Inquiry (the

DPSI) looks at the competition and consumer issues associated with the distribution of

mobile apps to users of smartphones and other mobile devices. This Report focuses on the

two key app marketplaces used in Australia: the Apple App Store (the App Store) and the

Google Play Store (the Play Store). These two app marketplaces dominate mobile app

distribution in Australia, with minimal use by Australians of rival app marketplaces and other

alternatives.

The ACCC’s examination of the operation of the Apple App Store and the Google Play Store

in Australia has identified a number of significant issues which warrant attention. These

include: the market power of each of Apple and Google; the terms of access to app

marketplaces for app developers, including payment arrangements; the effectiveness of self-

regulation, including arrangements to deal with harmful apps and consumer complaints; and

concerns with alleged self-preferencing and the use of data. These issues affect competition

with potentially significant impacts for both app developers and consumers.

This Report builds on the ACCC’s earlier work on digital platforms. Many of the findings in

relation to the dominant app marketplaces mirror those in the ACCC’s original Digital

Platforms Inquiry Final Report (DPI Final Report),

1

including the ability and incentive of large

platforms such as Apple and Google to each favour their own related businesses at the

expense of other businesses using their app marketplaces, and a lack of transparency. This

Report highlights the continued importance of particular recommendations from the DPI

Final Report, where they have applicability to the operation of app marketplaces.

A key area of focus for this Report is the concerns raised with the ACCC that Apple and

Google’s ability to set and enforce the rules governing access to the App Store and the Play

Store can harm competition and negatively impact app developers and/or consumers. This is

an area where the ACCC considers more can be done by Apple and Google, including in

order to meet expectations that they should not leverage their market power, and the access

they have to commercial information, to advantage themselves to the disadvantage of rival

apps. This Report identifies, as potential measures, those steps that could be undertaken by

Apple and Google; however, regulation may be required if they fail to do so. The ACCC

notes that a number of jurisdictions have already, or are proposing to, put in place rules

governing the conduct of digital platforms which meet certain thresholds.

The ACCC will revisit the issues raised in this Report during the course of the five-year DPSI

and, in revisiting these issues, the ACCC will consider developments in the relevant markets

and the steps taken by Apple and Google to address the issues identified here. The ACCC

will also take into account the overseas developments that aim to address the same

competition and consumer concerns that have been identified in this Report.

App marketplaces are critical gateways to reach consumers

Most adult Australians own a smartphone and use the apps installed on it many times a day

to engage with friends, family and colleagues, for entertainment, work and to complete tasks

such as banking, booking appointments and accessing critical information and services.

Consumers rely on the ability to complete a multitude of tasks wherever they are; apps

1

ACCC, Digital Platforms Inquiry Final Report, 26 July 2019.

4

installed on mobile devices make this possible. Worldwide, there are now over two million

apps on the App Store,

2

and around three million apps on the Play Store.

3

App marketplaces are digital shopfronts that provide a centralised distribution platform for

developers to offer and distribute their apps, and for consumers to discover, download and

update apps. Australian consumers overwhelmingly choose and install their apps from the

Apple App Store or the Google Play Store. Apple and Google, via their respective operating

systems (OS) and their app marketplaces, are therefore critical intermediaries or gateways

between app developers and consumers. The operation and policies of these critical

gateways have important implications for users on both sides of the platform: developers of

apps, and app consumers. This Report considers both sets of users but first examines the

market power that is held by the two dominant app marketplaces.

Apple and Google’s market power in app marketplaces and the link to

their mobile operating systems

Mobile apps are installed on the mobile OS that operate and control the functionality of

mobile devices, predominantly smartphones and tablets.

Google, with its Android OS, and Apple, with iOS, account for close to 100% of the global

market (excluding China) for mobile OS. Google has approximately 73% of this market and

Apple has around 27%.

4

Apple and Google also dominate the Australian market, each

holding around 50% of this market.

5

The duopoly in the market for mobile OS and the significant barriers to entry and expansion

provide each of Google and Apple significant market power in the supply of mobile operating

systems in Australia.

The ownership and control of their respective OS give Apple and Google control over the

distribution of mobile apps on their respective mobile ecosystems. Apple does not allow the

installation of app marketplaces (other than the App Store) on iOS mobile devices and while

other app marketplaces can be installed on Android mobile devices, Google uses its control

of Android to preference its own app marketplace, with the Play Store pre-installed on the

vast majority of Android devices. As a result, over 90% of apps available on Android mobile

devices are downloaded using the Play Store.

6

Apple and Google’s dominance in mobile OS, combined with the control exerted over the

app marketplaces permitted into their mobile ecosystems, means that the App Store and the

Play Store control the key gateways through which app developers can access consumers

on mobile devices. As there are limited effective alternatives to access consumers on mobile

devices, the App Store and the Play Store are ‘must haves’ for the majority of app

developers in Australia. This provides Apple and Google with market power in mobile app

distribution in Australia, and the ACCC considers it likely that this market power is significant.

2

Statista estimates that as of Q4 2020, there were almost 2.09 million available apps for iOS in the App Store. See Statista,

Number of apps available in leading app stores as of 4th quarter 2020

, accessed 24 March 2021. Apple submits that there

are 1.8 million apps available on the App Store. See Apple, Submission to the ACCC Digital Platform Services Inquiry

Second Interim Report, 2 October 2020, p 1.

3

AppBrain estimated there were 2,992,327 Android apps on Google Play as of 23 March 2021. See AppBrain, Number of

Android apps on Google Play, accessed 24 March 2021.

4

Statista, Mobile operating systems’ market share worldwide from January 2012 to January 2021, 8 February 2021,

accessed 16 March 2021.

5

Kantar reports estimated smartphone sales shares of around 54% for Android OS and 46% for iOS for the three months

ending December 2020. See Kantar, Smartphone OS market share

, 2020, accessed 24 March 2021. StatCounter reports

estimated mobile OS shares of 54% for iOS and 46% for Android OS for December 2020, based on mobile OS shares of

webpage views. See StatCounter,

Mobile operating system market share Australia, 2021, accessed 24 March 2021.

6

See US Department of Justice v Google LLC, Complaint filed in the US District Court for the District of Columbia,

20 October 2020, p 24.

5

App developer concerns with the operation of the dominant app

marketplaces

Given the market power held by Apple and Google respectively and the reliance of app

developers on the App Store and the Play Store to reach consumers, the ACCC has

scrutinised Apple and Google’s policies and practices to assess their potential effects on

competition.

The ACCC has focused on those issues that app developers have expressed most concern

with, that is, the terms and conditions imposed by Apple and Google, alleged self-

preferencing of their own first-party apps including via their access to the data generated by

third-party apps, as well as in-app payments and related terms.

In assessing the competitive implications of these practices and policies, it is important to

recognise that competition occurs, or can occur, at two levels. At one level there is

competition between mobile ecosystems.

7

At another level there is competition within

Apple and Google’s mobile ecosystems.

Apple and Google make differentiated offers to attract and retain customers on their mobile

ecosystems. Apple operates a closed system while Google allows third-party mobile devices

to use its OS. In relation to app marketplaces, however, the practical difference between

Apple and Google is minimal. While Google allows third-party app marketplaces on Android

and the loading of Android apps directly from a developer’s website, Google’s control of the

Android OS enables it to advantage the Play Store, including through the requirement for

device manufacturers seeking to pre-install desired Google apps to also pre-install the Play

Store. In practice, the Play Store is effectively isolated from competition and is not in a

dissimilar position to the App Store.

As set out below, the practices and policies of both Apple and Google restrict competition to

distribute mobile apps within their respective mobile ecosystems. Some of these practices

may, however, form part of the way in which Apple and Google compete with each other to

attract and retain customers on their mobile ecosystems. The ACCC recognises this level of

competition and considers it important to ensure that any measures proposed to increase

competition within mobile ecosystems do not lessen competition between mobile

ecosystems.

Terms of access

Particular concerns raised by app developers in relation to access to the App Store and the

Play Store identified during the DPSI include:

• unfair terms including restrictions on the ability of app developers to access the users of

their apps

• a lack of transparency in the policies and processes governing Apple and Google’s app

review and approval process, and

• inadequate avenues to resolve disputes.

The ACCC recognises that processes for the review and approval of apps are appropriate

and necessary to ensure that apps that pose harms to users or could undermine the integrity

and performance of mobile OS are excluded.

However, fair and reasonable terms and efficient, timely processes for the review and

approval of apps are of critical importance to app developers. In particular, app developers

7

We use the term ‘mobile ecosystem’ to refer to mobile operating systems and the mobile devices and software products

that make use of mobile operating systems.

6

have expressed concerns that Apple and Google’s enforcement of their rules in the app

review process appears to be applied inconsistently, with reasons for rejection not always

easily understood and with limited avenues of appeal. This can lead to inefficient business

decisions and unduly restrict or prevent the innovation and the emergence of disruptive

business models.

The US House Report on Competition in Digital Markets observed that the terms and

conditions imposed by Apple and Google to determine access to their respective app

marketplaces may be to the detriment of app developers as it ‘requires concessions and

demands that carry significant economic harm, but that are “the cost of doing business”

given the lack of options.’

8

The ACCC is continuing to closely monitor and consider issues raised by app developers

about the terms of access to Apple and Google’s app marketplaces.

The ACCC also notes that the DPI Final Report recommended:

• the development of minimum internal dispute resolution standards to apply to digital

platforms, covering among other things, the visibility, accessibility, responsiveness,

objectivity, confidentiality and collection of information of digital platforms’ internal

dispute resolution processes (recommendation 22), and

• the introduction of external oversight of the digital platforms to resolve complaints

between platforms and businesses and platforms and consumers via an ombudsman

scheme (recommendation 23).

These recommendations were recommended to cover complaints or disputes from

businesses and complaints or disputes from consumers including in relation to scams and

the removal of scam content. These recommendations may assist in the context of concerns

raised in relation to app marketplaces, as they could help ensure Apple and Google address

concerns raised by third-party app developers about the app review process.

Risk of self-preferencing

Apple and Google each offer their own apps (first-party apps), which compete directly with

apps developed by third parties (third-party apps) reliant on Apple and Google’s app

marketplaces.

The ACCC is concerned that, given their market power and their related activities, Apple and

Google each have the ability and the incentive to favour their own first-party apps at the

expense of rival third-party apps, and that such conduct may have anti-competitive effects

on downstream markets. Developers identified the following practices in submissions to the

ACCC:

• first-party apps benefit from being pre-installed or set as defaults

• first-party apps reportedly benefit from greater discoverability on the app marketplaces

• first-party apps benefit from greater access to functionality, or from a competitive

advantage gained by withholding access to device functionality to rival third-party apps.

A number of Apple and Google’s own apps clearly benefit from being pre-installed or set as

defaults and/or having superior integration with the relevant OS. Pre-installation and defaults

may entrench market power, limit consumer choice, and reduce potential for innovation in

the downstream markets in which they compete.

8

Subcommittee on Antitrust, Commercial and Administrative Law of the Committee of the Judiciary, Investigation of

Competition in Digital Markets: Majority Staff Report and Recommendations, 6 October 2020, p 11.

7

The introduction of ‘choice screens’, which display different app options for users prior to

use, are an option that may go some way to addressing any anti-competitive effects

associated with pre-installation or default settings. The ACCC is looking at how choice

screens may address concerns in relation to some digital platform services in its next interim

report.

9

Potential measure to provide for greater choice of default apps for consumers

There is a need for consumers to have more choice through an ability to change any pre-

installed default app on their device that is not a core phone feature. This would provide

consumers with more control to choose the app that best meets their needs, and promote

more robust competition in downstream markets for apps.

The ACCC will also continue to consider how choice screens may address some of the

concerns associated with pre-installation or default settings.

Concerns that first-party apps and apps that generate commission revenue for the app

marketplace benefit from greater discoverability, or that third-party apps are unjustifiably

penalised in ranking and discoverability, are difficult for the ACCC to assess given the

opacity of the algorithms determining ranking and discoverability in the app marketplaces.

However, the ACCC notes that independent research suggests that these practices may be

occurring.

10

Some app developers submitted that Apple and Google should make more information

available regarding the operation of their respective search algorithms that determine

discoverability on the App Store and Play Store, as well as provide greater advance notice of

impending changes to the algorithms (given the difficulties of third-party app developers to

adapt). In addition to the more general benefits associated with reducing opacity, greater

transparency may go some way to both detecting anti-competitive self-preferencing and

providing third-party app developers with greater confidence that this is not occurring.

However, the ACCC recognises the legitimate concerns of the app marketplaces that greater

transparency of the discoverability algorithms is likely to increase the risk of gaming.

Developers are also concerned about instances where third-party apps do not have access

to the same functionality accessed by Apple and Google’s first-party apps, preventing them

from competing effectively, potentially to the detriment of product innovation and consumer

choice. Information provided to the ACCC indicates that Apple limits access by third-party

apps to a greater number of application programming interfaces (APIs) than does Google.

The self-preferencing concerns identified in this Report are similar to concerns recognised

by the ACCC in relation to online search and social media in the DPI Final Report and in

relation to Google’s ad tech services in the Digital Advertising Services Inquiry Interim

Report.

11

In each case, the platform holds market power at one or more levels of the market

and competes with rivals at another level. The risk of self-preferencing in each of these

scenarios is increased given the opacity of the applicable algorithms and/or auctions.

Multiple solutions have been identified internationally to address this issue of self-

preferencing. These include structural separation of vertically integrated platforms, and the

introduction of a per-se prohibition which would effectively ban or restrict a platform with

9

See ACCC, Digital Platform Services Inquiry Third Interim Report – Issues Paper, 11 March 2021.

10

T Mickle, ‘Apple Dominates App Store Search Results, Thwarting Competitors’, The Wall Street Journal, 23 July 2019,

accessed 24 March 2021; J Nicas and K Collins, ‘How Apple’s Apps Topped Rivals in the App Store It Controls’, The New

York Times, 9 September 2019, accessed 24 March 2021; Subcommittee on Antitrust, Commercial and Administrative

Law of the Committee of the Judiciary,

Investigation of Competition in Digital Markets: Majority Staff Report and

Recommendations, 6 October 2020, p 361.

11

ACCC, Digital Advertising Services Inquiry Interim Report, 28 January 2021.

8

particular characteristics self-preferencing its services and products over those of third

parties.

12

At this stage in the DPSI, the ACCC will continue to monitor and explore self-preferencing

allegations as well as the impact of pre-installation or default settings. The ACCC is also

considering the broader issues that arise when digital platforms occupy critical gatekeeper

roles and at the same time compete with those businesses that rely on access to the

gatekeeper platform. As part of this process, the ACCC is considering both the extent of

these concerns and the solutions being put forward overseas, including recent amendments

to the German Competition Act as well as proposals by the United Kingdom Competition and

Markets Authority (CMA) and the European Commission.

In the meantime, the ACCC considers that greater transparency and more information on the

operation of app discoverability mechanisms, as well as a level playing field for apps to

receive consumer ratings and reviews, would go some way to addressing app developer

concerns with self-preferencing.

Digital platforms such as Apple and Google that control access to markets in which they

themselves participate have an incentive to set and enforce rules to their own advantage.

Measures are required to discourage or prohibit digital platforms with market power from

acting in this way. Two such measures are:

Potential measure to increase transparency and address risk of self-preferencing in

app marketplace discoverability and display

There is a need for greater transparency about key algorithms and processes determining

discoverability including impending changes to the key parameters used by algorithms

and editorial processes to enable app developers to adapt in a timely way.

Increased transparency would help address third-party app developers’ concerns that

algorithms and other processes determining discoverability are treating all apps equally

on their merits and that certain apps receive preferential treatment.

Potential measure to provide an option for consumers to rate and review first-party

apps

To enable third-party apps to compete on their merits and ensure informed consumer

choice consumers should be able to rate and write reviews on all apps including Apple

apps on the App Store and Google apps on the Play Store.

The ACCC will continue to monitor these markets and explore self-preferencing

allegations, as well as the impact of defaults.

Data practices of app marketplaces

Apple and Google have superior access to information about the entire app ecosystem and

its users, which enables them to monitor the performance of all apps and hence gain

valuable competitive insights. There are potential competition concerns arising from Apple

and Google’s intelligence gathering given that their own first-party apps compete with third-

party apps in downstream app markets.

Similar to the issue of self-preferencing, the ACCC considers that Apple and Google may

have the ability and the incentive to use information to assist strategic or commercial

decisions about first-party app development. Such conduct may insulate first-party apps from

12

European Commission, The Digital Markets Act: Ensuring fair and open digital markets, accessed 24 March 2021.

9

competition, reduce developers’ incentives to innovate, and reduce the quality and choice of

apps for consumers.

The ACCC will continue to explore this issue during the course of the DPSI, but at this stage

is of the view that there is an opportunity to support improved competition in the market for

apps through measures that address misuse of commercially sensitive information.

Potential measure to address the risk of misuse of commercially sensitive

information

There is a need for information collected by Apple and Google in their capacity as app

marketplace operators to be ring-fenced from their other operations and business

decisions. This would minimise the risk of this information being used to provide Apple

and Google with an unfair competitive advantage over third-party app developers in

downstream markets for apps.

In-app payments

Multiple app developers have raised concerns with the ACCC in relation to the commission

rates charged by Apple and Google on payments made for digital goods through apps (in-

app payments) and the associated terms.

Apple and Google both require that certain in-app payments must be processed through

their respective in-app payment systems. Apple and Google both impose a commission of

30% on these payments, although there are circumstances where the rate is 15%. Both

Apple and Google recently expanded the circumstances in which only 15% is required to be

paid.

13

Both app marketplaces provide that an app is not permitted to contain information

that directs users to an off-app payment option.

The commission is charged by Apple and Google on all in-app payments processed via their

respective in-app payment systems. However, many and indeed the vast majority of apps do

not process payments via the in-app payment systems, principally because they do not offer

their users in-app payment for digital goods and are therefore not required to use the Apple

and Google in-app payment systems.

The ACCC considers that the lack of competitive constraint in the distribution of mobile apps

is likely to affect the terms on which Apple and Google make access to their respective app

marketplaces available to app developers, including the commission rates and terms that

prevent certain app developers from using alternative in-app payment systems and

promoting alternative off-app payment systems.

The ACCC considers that the commission rates are highly likely to be inflated by the market

power that Apple and Google are able to exercise in their dealings with app developers.

Apple and Google structure their charges and their levels in order to maximise their profits.

For apps, this is about setting commission rates based on the likely ability and willingness of

app developers to pay, and, to the extent possible, minimising any flow on effects to

consumers. While the ACCC considers the market power of Apple and Google is highly

likely to mean that the commission rates are higher than otherwise would be the case, it is

difficult to know by how much. There are a couple of reasons for this.

First, it is difficult to predict the level of charges a mobile ecosystem is likely to impose in the

absence of market power. This is particularly the case given charges for the use of a mobile

ecosystem are, in the main, not cost-based. For some costs, such as the costs of developing

13

Apple, App Store Small Business Program, accessed 24 March 2021; S Samat, ‘Boosting developer success on Google

Play’, Android Developers Blog, 16 March 2021, accessed 24 March 2021.

10

and maintaining mobile operating systems, there may be no direct revenue source. These

costs are common to a range of services provided by a mobile ecosystem. Moreover, in

setting charges, operators of mobile ecosystems take into consideration the effect on the

overall use of the system. This is made complex by the significant interdependencies

between different users of mobile ecosystems. For instance, setting commission rates for in-

app payments involves taking into account the likely reactions of both consumers and app

developers. While this is the case, the ACCC notes that Apple and Google both achieve

substantial revenues from developer fees and in-app commissions and these revenues are

likely to be substantially larger than the direct costs of their respective app marketplaces.

Second, there are no clear benchmarks with which the commission rates can be compared.

While Apple has highlighted similarities between commissions charged on the App Store and

those charged on other app and games marketplaces, it is not compelling evidence as to

what commission rates might be in the absence of its market power. It is quite possible that

the commission rates set by Apple and Google are used as ‘market’ benchmarks and

replicated by other app or games marketplaces.

The ACCC notes that Apple and Google’s in-app payment requirements, including the level

of the commission, are the subject of litigation by Epic Games in a number of jurisdictions

including the United States, the United Kingdom and Australia. The CMA, the European

Commission and the Netherlands Consumers and Markets Authority have also announced

investigations into in-app purchasing rules put in place by Apple.

The ACCC notes calls for measures that would require Apple and Google to unbundle their

in-app payment systems from their respective app marketplaces to allow third parties to

provide the payment service. A less disruptive measure may be to allow apps to inform their

users of alternative off-app payment options. This would provide greater choice and

potentially lower prices to consumers and allow app developers greater scope to innovate.

Broad proposals put forward by the CMA and the European Commission seek to address

both the cause and consequences of the market power held by digital platforms in a range of

markets. These include potential provisions that would likely prevent app marketplaces (and

other platforms reaching particular thresholds) from putting in place restrictions that would

prevent apps from informing users of alternative off-app payment options.

The ACCC will continue to consider the competition concerns raised in relation to Apple and

Google’s in-app payment policies during the course of the DPSI, as well as potential

regulatory measures that may address these concerns. At this point in the DPSI, the ACCC

has identified the following as a potentially effective and proportionate measure to address

the concerns identified.

Potential measure to address inadequate payment option information and

limitations on developers

App developers should not be restricted from providing users with information about

alternative payment options. This would provide greater choice and potentially lower

prices to consumers and allow app developers greater scope to innovate.

Harmful apps and consumer complaints handling

Addressing the risk of harmful apps

The widespread use of mobile apps by consumers attracts those seeking to scam or

otherwise harm consumers through the use of malicious or exploitative apps.

11

Apple and Google’s app review functions provide important protections for consumers and

the ACCC recognises that in comparison to alternative sources of apps, apps downloaded

from the Play Store and the App Store are far less likely to harm consumers or their devices.

Apple and Google also promote the view that strict oversight of their app marketplaces is

fundamental to their ability to provide consumers with safe platforms for accessing apps.

However, consumer feedback and analysis of app marketplace reviews suggests apps with

the potential to harm consumers continue to be present on both app marketplaces.

The apparent availability of harmful apps that the ACCC considers consumers may

reasonably expect to have been identified through initial marketplace review and ongoing

surveillance processes indicates Apple and Google’s existing processes fail to adequately

protect consumers.

In the ACCC’s view, Apple and Google could do more to protect app users, including

children who may be exposed to age-inappropriate apps.

Potential measure to address the risks of malicious, exploitative or otherwise

harmful apps

The ACCC considers that app marketplaces should do more to address the risks

associated with harmful or malicious apps (such as subscription traps or real prize

scams). While both Apple and Google have publicly stated their commitment to protect

consumers from harmful apps, and both have policies in place that are intended to

facilitate this, the ACCC considers that Apple and Google should take steps to more

proactively monitor those apps which have made it through their review processes and

are available on their app marketplaces for continued compliance with their marketplace

policies.

There appear to be a number of ways Apple and Google could potentially do this,

including through their monitoring of consumer app reviews and the implementation of a

process for active consideration and intervention if certain triggers are met (based on, for

example, the substantiality or duration of non-compliance, or the numbers of consumers

affected).

Continued concerns with the tracking of consumers through apps

The ACCC remains concerned with the tracking of consumers through apps. Many

consumers express strong preferences for limitations on tracking, yet the data practices of

apps available on the App Store and Play Store often do not align with the those preferences

(as discussed in chapter 7). In the ACCC’s view, while Apple in particular is taking positive

steps to better protect the privacy of app users, there are some key limitations in both Apple

and Google’s policies and processes pertaining to the data practices of app developers and

their third-party partners.

The ACCC continues to support the DPI Final Report recommendations regarding amending

the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 to prohibit unfair contract terms

(recommendation 20) and certain unfair trading practices (recommendation 21) which will

benefit the many consumers who use apps.

App marketplace complaints handling processes may not be adequate

The ACCC considers that consumers must have adequate access to avenues for redress

from app marketplaces for losses caused by malicious apps, low quality apps, unauthorised

billing issues and where they are otherwise entitled to a remedy under the Australian

Consumer Law (ACL). This includes the ability to escalate their complaints to an external

12

body if they are not satisfied with the outcome of the app marketplace’s dispute resolution

processes.

In the ACCC’s view, Apple and Google are not currently achieving a balance that best

serves their users; between providing streamlined, consistent processes for consumer

complaints on the one hand, and supporting developers to fulfil the complaints handling

functions required of them by the marketplaces on the other.

The ACCC continues to support the DPI Final Report recommendations regarding internal

dispute resolution mechanisms (recommendation 22) and the establishment of an

ombudsman scheme to resolve complaints and disputes with digital platforms

(recommendation 23) In addition to addressing key concerns raised by third-party app

developers about the inadequate avenues to resolve disputes with app marketplaces (as

discussed above), these recommendations could also cover complaints and disputes from

consumers of apps, including in relation to scams and the removal of scam content. Applying

these dispute resolution proposals to app marketplaces would help address deficiencies in

the app marketplace dispute resolution mechanisms currently available to consumers.

Overseas developments and the importance of international cooperation

The large digital platforms covered by the DPSI, including those considered in this Report,

operate globally.

The global activities of these platforms and the critical role they perform in the economy, and

society more broadly, has meant competition and consumer agencies around the world are

investigating their activities, and in many cases proposing policies that address the

consequences of their market power and potential consumer harm.

Key developments include the recent amendments to the German Competition Act that puts

in place a series of per-se prohibitions on those platforms that are designated to have

‘paramount significance for competition across markets’.

14

These prohibitions include

banning self-preferencing that, for example, is likely to include self preferencing achieved via

the pre-installation of proprietary apps.

The changes to German competition law are part of a broader shift in overseas jurisdictions

to address the challenges posed by fast evolving digital markets by initiating legislative

change and sit alongside the European Commission’s draft Digital Markets Act.

15

This

would place a series of ex ante rules on large digital platforms which act as ‘gatekeepers’

between businesses and users, aiming to prevent them unfairly benefiting from their

strategically important positions and the UK Competition and Market Authority’s proposals

for codes of conduct to apply to those digital platforms which occupy ‘strategic market

status’.

16

In addition, far-reaching options for legislative reform have been set out in the US House

Report on Competition in Digital Markets,

17

and there are ongoing hearings by both the

House Judiciary Subcommittee on Antitrust, Commercial and Administrative Law,

18

and the

Senate Judiciary Subcommittee on Competition Policy, Antitrust, and Consumer Rights, into

14

D’Kart, German Act against Restraints of Competition (Unofficial translation), 14 January 2021; P Bongartz, ‘Happy New

GWB!’, D’Kart Antitrust Blog, 14 January 2021, accessed 24 March 2021.

15

European Commission, Statement by Executive Vice-President Vestager on the Commission proposal on new rules for

digital platforms, 15 December 2020, accessed 24 March 2021; European Commission, The Digital Markets Act: Ensuring

fair and open digital markets, accessed 24 March 2021.

16

CMA, A new pro-competition regime for digital markets: Advice of the Digital Markets Taskforce, 8 December 2020.

17

Subcommittee on Antitrust, Commercial and Administrative Law of the Committee of the Judiciary, Investigation of

Competition in Digital Markets: Majority Staff Report and Recommendations, 6 October 2020.

18

See, for example, Subcommittee on Antitrust, Commercial and Administrative Law, Reviving Competition, Part 1:

Proposals to Address Gatekeeper Power and Lower Barriers to Entry Online, 24 February 2021, accessed 24 March 2021.

13

issues raised by digital platforms.

19

Japan has also introduced laws requiring specified digital

platforms to increase transparency and increase fairness and the South Korean Fair Trade

Commission (KFTC) has proposed reform aimed at regulating dominant online platform

operators and increasing fairness in online platform transactions.

20

The ACCC is closely following legislative reform in this area and engaging with our overseas

counterparts.

This Report, which focuses on one particular type of digital platform service, app

marketplaces, aims to contribute to the international consideration of the competition and

consumer issues associated with digital platforms and builds on the ACCC’s First DPSI

Interim Report and the DPI Final Report. In setting out its findings and potential measures in

this interim Report, the ACCC has sought to highlight those areas that require redress by

digital platforms.

As set out above, the ACCC will continue to explore during the course of the five-year DPSI

these issues and developments in the relevant markets including steps taken by digital

platforms to address the concerns identified. The ACCC’s consideration will also be informed

by overseas learning and proposals. In addition to important benefits in sharing knowledge

and experiences, the ACCC also recognises the value of greater regulatory coherence in

addressing the competition and consumer issues associated with digital platforms.

Measures to address competition and consumer issues in app

marketplaces

DPI recommendations

Four recommendations from the DPI Final Report are particularly relevant to the concerns

identified in this Report.

Recommendations 20 and 21 – Prohibition of unfair contract terms and certain unfair

trading terms.

Recommendations 22 and 23 – Internal dispute resolution mechanisms and an

ombudsman scheme to resolve disputes.

The ACCC continues to support these recommendations and the applicability of these

proposals to app developer and consumer interactions with Apple and Google’s app

marketplaces. See chapter 3 and chapter 6 for discussion of app developer and consumer

issues respectively, and chapter 7 for discussion of Apple and Google’s data practices and

of apps available on the App Store and Play Store.

Potential measures

The ACCC has further concerns relating to outcomes for both app developers and

consumers arising from Apple and Google’s regulation of access to the app marketplaces.

The ACCC has set out as potential measures in this Report the actions needed to reduce

harms arising from Apple and Google’s freedom to set rules for their respective

marketplaces. The ACCC will continue to monitor and explore issues identified in this Report

as well as broader issues that arise when digital platforms occupy critical gatekeeper roles

and, at the same time, compete with those businesses that rely on access to gatekeeper

platforms. The ACCC will revisit these concerns in a later interim report and, as part of this

19

Apple Insider Staff, ‘Sen. Amy Klobuchar plans to hold antitrust subcommittee hearings on App Store’, Apple Insider,

11 March 2021, accessed 24 March 2021.

20

K Toda, ‘Japan: Latest Developments On The Regulation Of Digital Platformers From A Competition Law Perspective’,

Mondaq, 8 July 2020, accessed 24 March 2021; SY Jung, ‘Law to Be Enacted for Fair Online Platform Transactions’,

Business Korea, 29 September 2020, accessed 24 March 2021.

14

process, consider overseas developments and whether there is a need for regulation to

address the concerns identified.

The potential measures to address the concerns identified in this Report are:

Potential measure 1: to address inadequate payment option information and limitations on

developers (chapter 4)

There is a need for greater awareness about the payment options available to consumers through an

obligation on marketplaces to allow developers to provide users with information about alternative

payment options.

Potential measure 2: to increase transparency and address risk of self-preferencing in app

marketplace discoverability and display (chapter 5)

There is a need for greater transparency about key algorithms and processes determining

discoverability including impending changes to the key parameters used by algorithms and editorial

processes to enable app developers to adapt in a timely way.

Potential measure 3: to provide an option for consumers to rate and review first-party apps

(chapter 5)

To enable third party apps to compete on their merits with first-party apps and ensure informed

consumer choice, there is a need for consumers to be able to rate and write reviews on all apps put on

the App Store by Apple and on the Play Store by Google.

Potential measure 4: to provide for greater choice of default apps for consumers

(chapter 5)

There is a need for consumers to have more choice through an ability to change any pre-installed

default app on their device that is not a core phone feature. This would provide consumers with more

control to choose the app that best meets their needs, and promote more robust competition in

downstream markets for apps.

Potential measure 5: to address the risks of malicious, exploitative or otherwise harmful apps

(chapter 6)

The ACCC considers that app marketplaces should do more to address the risks associated with

harmful or malicious apps (such as subscription traps or real prize scams). While both Apple and

Google have publicly stated their commitment to protect consumers from harmful apps, and both have

policies in place that are intended to facilitate this, the ACCC considers that Apple and Google should

take steps to more proactively monitor those apps which have made it through their review processes

and are available on their app marketplaces for continued compliance with their marketplace policies.

There appear to be a number of ways Apple and Google could potentially do this, including through

their monitoring of consumer app reviews and the implementation of a process for active consideration

and intervention if certain triggers are met (based on, for example, the substantiality or duration of non-

compliance, or the numbers of consumers affected).

Potential measure 6: to address the risk of misuse of commercially sensitive information

(chapter 7)

There is a need for information collected by Apple and Google in their capacity as app marketplace

operators to be ring-fenced from their other operations and business decisions. This would minimise

the risk of this information being used to provide Apple and Google with an unfair competitive

advantage over third-party app developers in downstream markets for apps.

15

Introduction

This is the second interim report (Report) provided to the Australian Government by the

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) as part of the five-year inquiry

into the supply of digital platform services (the DPSI). Further information, including the

Ministerial Direction for the Inquiry and information about the focus of the third interim report

due 30 September 2021 can be found here

.

This Report focuses on the operation of mobile app marketplaces in Australia, and the

experiences of Australian mobile app developers and mobile app users.

This Report is structured as follows:

• Chapter 1 provides an overview of mobile apps and app marketplaces in Australia.

• Chapter 2 sets out the ACCC’s assessment of the extent to which the App Store and the

Play Store are constrained by competition.

• Chapter 3 discusses the terms put in place by each of Apple and Google which govern

app developers’ access to their respective app marketplaces.

• Chapter 4 discusses the specific terms put in place by each of Apple and Google relating

to app payments.

• Chapter 5 explores the discoverability and display of apps, and the impact on

competition and for consumers.

• Chapter 6 discusses the malicious targeting of consumers through apps and the

adequacy of complaints handling measures.

• Chapter 7 provides an overview of the data practices of Apple and Google and the

impact on competition and consumers.

16

1. Overview of mobile apps and app marketplaces

• Smartphones are now the most popular device used by Australian consumers to

access the internet and online activities.

• The number and variety of apps available to Australian consumers continues to grow,

with social media, entertainment and communication apps the most commonly used.

• Apps are typically designed to run on a specific mobile operating system (OS) and

must interact with the OS in order to function. Apple (iOS) and Google (Android) are

the predominant mobile OS providers in Australia.

• Apps are predominately distributed on app marketplaces run by Apple and Google, the

App Store and the Play Store, respectively. Worldwide, the App Store offers

approximately two million apps,

21

and the Play Store approximately three million

apps.

22

• App marketplaces benefit consumers by providing secure and accessible platforms to

navigate and browse the multitude of apps available. App marketplaces benefit

developers by reducing the costs and barriers of reaching a large consumer audience.

This chapter provides an overview of the use of smartphones, apps and app marketplaces in

Australia and the benefits of app marketplaces for consumers and app developers, and is

structured as follows:

• Section 1.1 considers the rise of smartphones and apps in Australia.

• Section 1.2 outlines the mobile operating systems and app distribution in Australia.

• Section 1.3 discusses the benefits of app marketplaces for consumers and app

developers.

1.1. The rise of smartphones and apps in Australia

Smartphones are increasingly integral to the lives of Australians. Advances in technology

have led to smartphones that offer many of the capabilities of a personal computer within the

convenience of a small, portable device.

Not only do most Australians now have access to a smartphone (92% of Australian adults),

23

but they increasingly prefer to use their smartphones rather than laptops or computers to

carry out various tasks,

24

and access the internet.

25

As outlined in box 1.1, these activities

are typically carried out through apps.

21

Statista estimates that as of Q4 2020, there were almost 2.09 million available apps for iOS in the App Store. See Statista,

Number of apps available in leading app stores as of 4th quarter 2020

, accessed 24 March 2021. Apple submits that there

are 1.8 million apps available on the App Store. See Apple, Submission to the ACCC Digital Platform Services Inquiry

Second Interim Report, 2 October 2020, p 1.

22

AppBrain estimates there are 2,992,327 Android apps on Google Play as of 23 March 2021. See AppBrain, Number of

Android apps on Google Play, accessed 24 March 2021.

23

In 2020, 92% of Australian adults (18-75 years) had access to a smartphone, compared to 76% in 2013. See Deloitte

Australia, Digital Consumer Trends 2020 – Australian edition

, 2020, pp 4, 18.

24

Tasks where respondents preferred to use a phone rather than a laptop include online search, watching short videos,

checking bank balances, video calls, reading the news, playing games, checking social networks. See Deloitte Australia,

Digital Consumer Trends 2020 - Australian edition

, 2020, p 18.

25

The Australian Communications and Media Authority (ACMA) found that mobile phones were the most popular device

used to access the internet with 91% of Australian adults having accessed the internet from their mobile phone in the

6 months to June 2020, up 4% from the previous year’s reporting period. See ACMA,

Trends in online behaviour and

technology usage: ACMA consumer survey 2020, September 2020, p 4.

17

Box 1.1: What are apps?

For the purposes of this Report, apps refer to software applications used on a device, such as a

smartphone, which are downloaded from an app marketplace.

26

Apps are used to provide a wide

range of goods and services, including social media, games, entertainment, health and fitness, and

facilitating the purchasing of physical services, like food delivery and rideshare.

There are a variety of reasons for businesses to choose to develop an app. For example, some

apps facilitate communication between businesses and their customers, (as with banking apps and

apps used by governments service providers) while other apps are designed to facilitate

transactions with consumers to provide goods and services.

Apps may be offered to consumers as:

• Paid apps – apps that require a one-off payment in order to access or use the app in full.

• ‘Free’ (zero monetary price) apps – apps that consumers do not have to directly pay to use.

Many of these ‘free’ apps (but not all) generate revenue from the collection and use of user

data and/or by serving advertisements to users.

• ‘Free’ apps with in-app payments – apps that are free to download and use, but require ‘in-

app payments’ to access additional features, content or functionality. These payments can be

one-off, or a recurring payment for continuing access (such as subscription apps). These

payments are discussed in more detail in chapter 4.

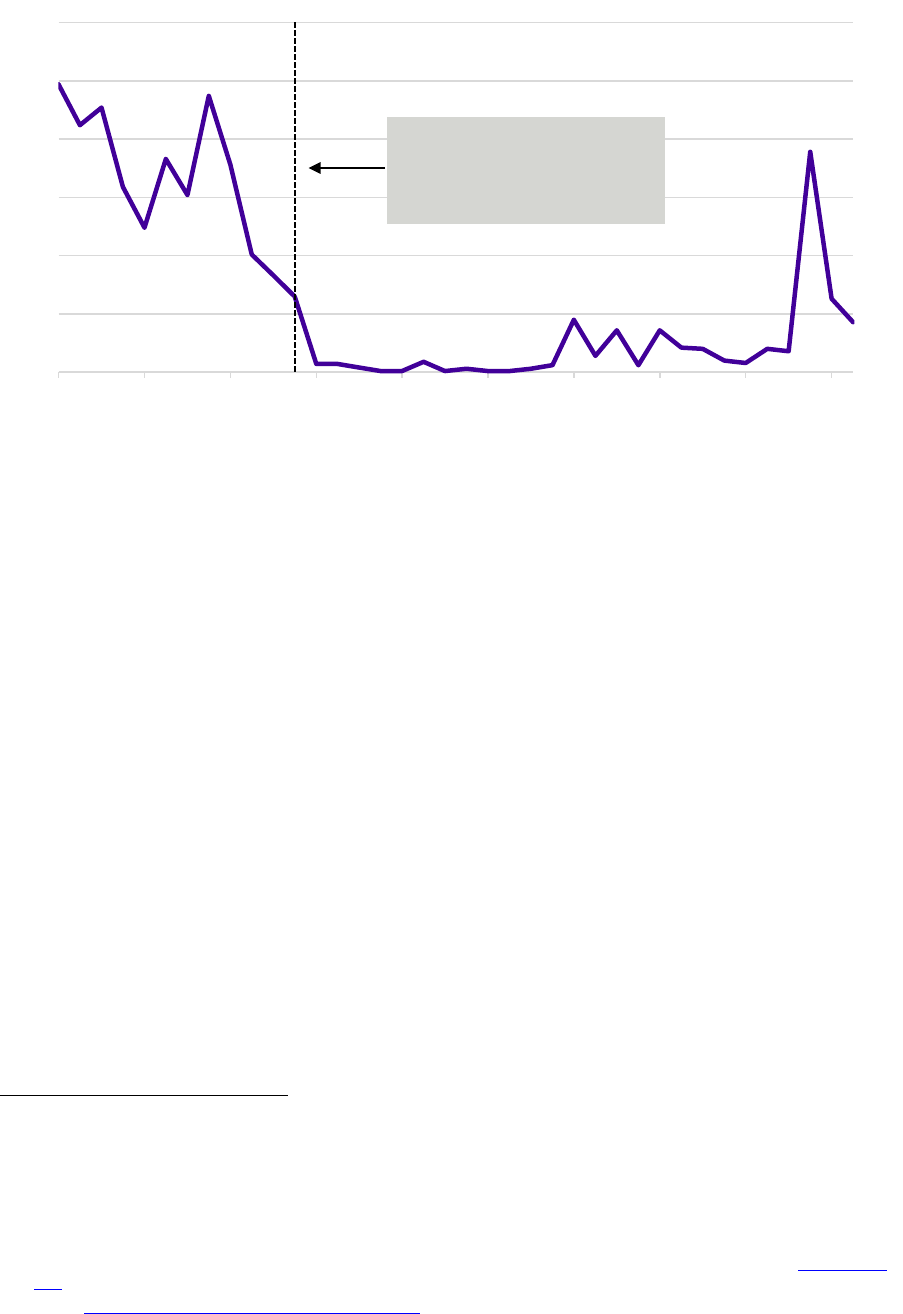

Over time, the number of apps available to consumers has increased significantly, and the

number of apps downloaded by Australian consumers has also grown over time, as shown

in figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1: Number of app downloads in Australia, January 2016 to December 2020

Source: Sensor Tower data.

According to Sensor Tower, the top three apps in Australia by daily active users in

January 2021, across both the Play Store and the App Store (for iPhone), were Facebook,

Facebook Messenger and Instagram, as shown in figure 1.2 below.

26

In the Report, references and discussion about apps predominately relates to apps downloaded from an app marketplace,

and may not necessarily apply to other types of apps, such as web apps. Where the Report refers to other types of apps,

such as web apps, this will be made clear. As discussed in chapter 2, web apps are internet enabled apps that are

accessible via web browsers on smartphone devices like a regular webpage.

-

50

100

150

200

250

App downloads (m)

Play Store App Store (iPhone)

18

Figure 1.2: Most popular apps in Australia by daily active users in January 2021

27

Source: Sensor Tower data.

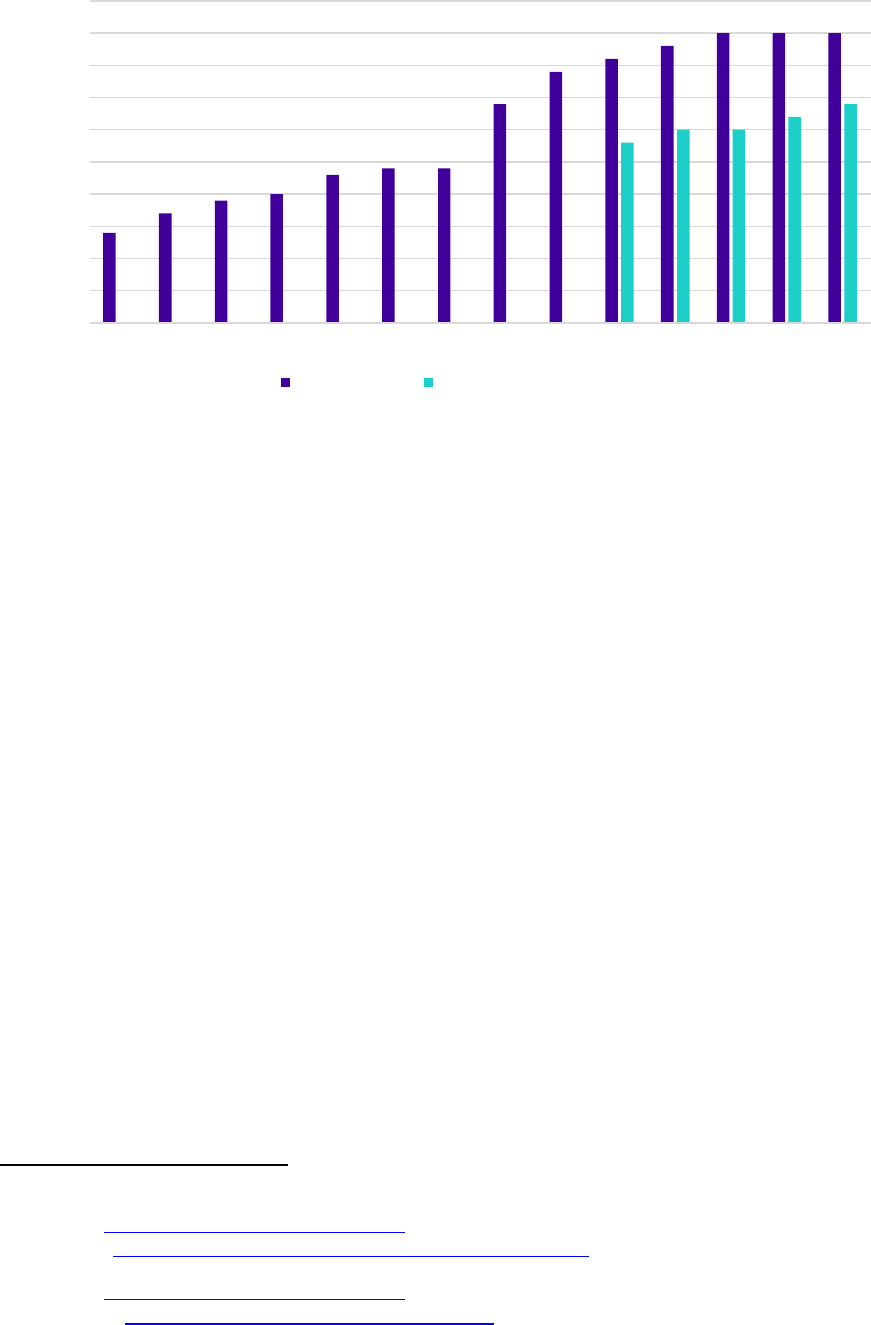

The popularity of these apps in Australia has been relatively consistent over time, as shown

in figure 1.3. In the last five years, nine apps have featured in the ‘top 15 apps’ by daily

active users in January each year for the Play Store and the App Store (for iPhone).

Figure 1.3: Select top apps in Australia by daily active users in January, 2017 to

2021

28

Source: ACCC analysis using Sensor Tower data.

In the future, apps may become even more important in daily life as consumers increasingly

interact with the world around them through their smartphones, such as to control devices

27

This chart captures the daily active users of apps where the app was downloaded from the App Store or Play Store, and

does not capture the number of users where an app comes pre-installed on a device, such as some Google apps (Gmail,

YouTube, Google Search), on many Android smartphones. This chart is based on Sensor Tower data.

28

This chart reflects apps that featured in the top 15 apps by daily active users in January for each year listed. The chart

does not reflect the ranking of the app within the top apps, but only that it fell within the top 15 each year. The figures

reflect combined active users for the Play Store and the App Store (for iPhone devices only).

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

Absolute users (m)

Play Store App Store (iPhone)

-

2

4

6

8

10

12

Jan-17 Jan-18 Jan-19 Jan-20 Jan-21

Absolute users (m)

Facebook Messenger Snapchat Instagram WhatsApp

Spotify CommBank Twitter Pinterest

19

connected through the Internet of Things (IoT).

29

In Australia, the number of downloads of

IoT-related apps such as Google Home, Amazon Alexa, Tile, Ring, Fitbit and Garmin

Connect in the last five years is shown in figure 1.4.

Figure 1.4: Example of IoT-related app downloads in Australia, January 2017 to

January 2021

30

Source: ACCC analysis using Sensor Tower data.

1.2. Mobile operating systems and app marketplaces

Mobile apps work in conjunction with the operating system (OS) running on the device on

which they are installed. Therefore mobile apps must be designed and built to run on a

specific OS. The OS operates in a similar way to operating systems on desktop or laptop

computers – controlling the hardware and software on a mobile device – including access to

the device’s camera, GPS, phone features and internet. More information on mobile OS is

set out in chapter 2.

Apple (iOS) and Google (Android) are effectively the only mobile OS providers in Australia

and globally (excluding China). Together, Apple and Google have close to 100% of the

mobile OS market worldwide, and in Australia, Apple and Google each have around 50% of

the mobile OS market.

31

Apple and Google’s respective mobile OS are discussed further

below and in chapter 2.

Mobile apps are predominately distributed on app marketplaces which are digital storefronts

that provide a centralised distribution platform for developers to offer and distribute their

apps, and for consumers to discover, download, and update apps. Apple and Google are the

predominant app marketplace operators, offering the App Store and the Play Store,

respectively. These app marketplaces are discussed further below and the level of the

competition they face is discussed in chapter 2.

The relationship between smartphones, operating systems and the app marketplaces is

illustrated in figure 1.5 below.

29

App Annie, The State of Mobile 2020, 2020, p 10.

30

The apps shown were selected by the ACCC as examples of IoT apps.

31

Kantar reports estimated smartphone sales shares of around 54% for Android OS and 46% for iOS for the three months

ending December 2020. See Kantar, Smartphone OS market share

, 2020, accessed 24 March 2021. StatCounter reports

estimated mobile OS shares of 54% for iOS and 46% for Android OS for December 2020, based on mobile OS shares of

webpage views. See StatCounter,

Mobile operating system market share Australia, 2021, accessed 24 March 2021.

-

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

Jan-17 Jan-18 Jan-19 Jan-20 Jan-21

Cumulative app downloads (m)

Google Home Amazon Alexa Garmin Connect

Fitbit Health Tile Ring

20

Figure 1.5: Layers relied on by an app marketplace

1.2.1. Apple iOS and the App Store

Apple is responsible for the operating system for iPhone and iPad devices – iOS. Apple’s

iOS is only available for and compatible with these devices and Apple does not allow

alternative OS on its devices.

Apple’s iOS is ‘closed source’. Its contents and code are not published or directly available

to third-party app developers. Apple maintains complete control over iOS and has the ability

to impose restrictions on how apps can interact with iOS. Apple provides a range of software

and tools to third-party app developers to enable them to build apps for iOS, such as Xcode

(to write apps),

32

Swift (to write code),

33

and TestFlight (to test apps before release).

34

Third-party app developers are bound by a number of agreements and guidelines about how

they can build and distribute apps for iOS, which are discussed in chapter 3.

Apps are distributed through Apple’s official app marketplace for iOS – the App Store –

which is pre-installed on all iOS devices (along with other Apple first-party apps, as

discussed in chapter 5). The App Store started with 500 apps in 2008 and has grown

exponentially,

35

now offering approximately two million apps.

36

Developers can only

distribute apps for iOS through Apple’s App Store and there is no alternative app

marketplace for iOS.

1.2.2. Google Android and the Play Store

Google is responsible for the overall direction of Android as a platform and product, and

oversees the development of the core Android open source platform.

37

In contrast to iOS, Android is, in principle, ‘open source’. Google publishes the source code

for anyone to access and modify as they wish, for any kind of device.

38

Android is not linked

32

Apple, Xcode, Apple Developer, accessed 24 March 2021.

33

Apple, Swift, Apple Developer, accessed 24 March 2021.

34

Apple, TestFlight, Apple Developer, accessed 24 March 2021.

35

Apple, Submission to the ACCC Digital Platform Services Inquiry Second Interim Report, 2 October 2020, p 4.

36

Statista estimates that as of Q4 2020, there were almost 2.09 million available apps for iOS in the App Store. See Statista,

Number of apps available in leading app stores as of 4th quarter 2020

, accessed 24 March 2021. Apple submits that there

are 1.8 million apps available on the App Store. See Apple, Submission to the ACCC Digital Platform Services Inquiry

Second Interim Report, 2 October 2020, p 1.

37

Android Source, Frequently Asked Questions, 2 March 2021, accessed 24 March 2021.

38

Modified versions of the published source code are called ‘Android forks’. However, Google is able to control the Android

ecosystem by maintaining a consistent single version of Android, across the vast majority of Android devices, under anti-

forking agreements. These agreements broadly prohibit device manufacturers from taking ‘any actions that may cause or

result in the fragmentation of Android’, as well as forbidding distribution of Android versions that do not comply with

Google’s standards as set out in the Android Compatibility Definition Document. See Android Source,

Android

Smartphone

A mobile phone with a variety of hardware sensors and

multimedia functionality.

Operating system

Software that manages the smartphone hardware and allows

apps to be run.

App marketplace

A platform on which apps are uploaded by developers and

downloaded by consumers.

21

to a particular hardware, and is used by a number of device manufacturers such as

Samsung, Amazon, and Huawei in their respective smartphones and other mobile devices.

However, similar to iOS, third-party app developers are bound by a number of agreements

and guidelines about how they can build and distribute apps for Android, which are

discussed in chapter 3.

Google owns and operates the official app marketplace for Android – the Play Store – which

is pre-installed on the vast majority of Android devices (along with other Google first-party

apps, as discussed in chapter 5). The Play Store launched in 2008 (under the name Android

Market) and has grown over time, now offering approximately three million apps worldwide.

39

Although there are alternative third-party app marketplaces for Android, discussed further

below, and there is no requirement that Android apps must come from the Play Store,

Google does not allow third-party app marketplaces to be downloaded from the Play Store.

1.2.3. Alternative ways for consumers to install mobile apps

There are limited alternative distribution channels for mobile apps beyond the App Store and

the Play Store.

While there are alternative app marketplaces for Android, such as the Amazon Appstore for

Android,

40

or the Samsung Galaxy Store,

41

these have significantly fewer apps than the Play

Store and are only available on specific devices. There are no alternative app marketplaces

for iOS.

Beyond app marketplaces, there are few options for consumers to download and install

apps, and these are technically difficult and unlikely to be undertaken by most smartphone

users. Alternative options for app distribution including the competitive impact of other app

marketplaces on the Play Store and the App Store are discussed in chapter 2.

1.3. Benefits of app marketplaces for consumers and app developers

App marketplaces provide benefits to both consumers and app developers. They offer a

secure and easily accessible way for consumers to navigate and browse the millions of

available apps, and help them find and install the apps that best meet their needs. For

developers, particularly smaller developers, app marketplaces (and app development tools)

help to reduce barriers and costs, and provide access to a large market of potential

consumers.

The value of an app marketplace to consumers is greater the more apps and app choice that

the marketplace offers and, similarly, app developers benefit the more consumers use the

marketplace.

42

1.3.1. Consumers

Both Apple and Google seek to create a positive user experience and help consumers

navigate their marketplaces by curating apps and offering discovery tools, such as ‘popular

app’ charts, editorial features and a search function within the marketplace. These tools are

discussed further in chapter 5.

Compatibility Definition Document, 8 September 2020, accessed 24 March 2021. This is also discussed further in

chapter 2.

39

AppBrain estimates there are 2,992,327 Android apps on Google Play as of 23 March 2021. See AppBrain, Number of

Android apps on Google Play, accessed 24 March 2021.

40

Amazon, Amazon Appstore App For Android, accessed 24 March 2021.

41

Samsung, Galaxy Store, accessed 24 March 2021.

42

These cross side network effects of two-sided markets have competition effects that are discussed in chapter 2.

22

Apple,

43

and Google,

44

also each take active measures to ensure a safe and secure platform

for consumers by vetting apps for malware or other malicious content, and provide some

avenues for recourse should an app not meet a consumer’s expectations. Apple, in

particular, emphasises the security and privacy of its platform and differentiates its product

by promoting these features.

Notwithstanding the convenience and benefits that apps in general provide consumers, a

number of apps can lead to consumer harm, particularly for more vulnerable consumers.

Apple and Google’s steps to safeguard consumers against these types of apps are

discussed in chapter 6.

1.3.2. App developers

App marketplaces benefit developers, particularly small and/or new developers, by providing

a platform that reaches a large audience with relatively minimal investment.

45

Apple and

Google also have incentives to offer a positive experience for app developers, as these

developers are critical to the success of the marketplace and its ability to offer diverse and

innovative apps to attract consumers.

The marketplaces also help developers increase their speed to market and distribution of

apps, and benefit developers as they have built-in consumer trust and security.

46

Some

developers credit their ability to commercialise to the existence of the app marketplaces, as

one developer expressed in response to the ACCC’s App Developer Questionnaire:

The app store is a valuable way to be able to distribute apps. I do not have the

resources to manage distribution of an app, payment and licensing systems,

ensuring security of the apps users download. The app store does this for me.

47

Apple and Google both also provide developers with access to various tools and resources

to assist them in developing, publishing, monetising, and marketing their apps through the

App Store Connect,

48

and Google Play Console,

49

respectively. Developers also benefit from

Apple and Google’s role in managing and maintaining various regulatory compliance

requirements through the app marketplace.

50

However, some developers have raised concerns with how the app marketplaces operate,

such as Apple and Google’s setting and enforcing of terms (discussed in chapter 3) including

app payments (discussed in chapter 4), the potential for self-preferencing through discovery

tools (discussed in chapter 5), and the use of information collected through the app

marketplace (discussed in chapter 7).

43

Subcommittee on Antitrust, Commercial and Administrative Law of the Committee of the Judiciary, Investigation of

Competition in Digital Markets: Majority Staff Report and Recommendations, 6 October 2020, p 97.

44

Google, Submission to the ACCC Digital Platform Services Inquiry Second Interim Report, 19 October 2020, p 7.

45

Apple, Submission to the ACCC Digital Platform Services Inquiry Second Interim Report, 2 October 2020, p 4.

46

ACCC, App marketplaces report – App developer questionnaire responses, 27 November 2020, response 66.

47

ACCC, App marketplaces report – App developer questionnaire responses, 27 November 2020, response 6.

48

Apple, App Store Connect, accessed 24 March 2021.

49

Google, Google Play Console, accessed 24 March 2021.

50

Google, Submission to the ACCC Digital Platform Services Inquiry Second Interim Report, 19 October 2020, p 6.

23

2. Competition Assessment

• The duopoly nature of the market for mobile operating systems and the significant

barriers to entry and expansion provide each of Apple and Google significant market

power in the supply of mobile operating systems in Australia.

• Apple and Google face limited competitive constraints in mobile app distribution. The

lack of strong competitive constraints faced by Apple and Google provides each with

market power in mobile app distribution in Australia and the ACCC considers it likely

that this market power is significant. This market power particularly affects the dealings

of app developers with Apple and Google in Australia.

• iOS users and app developers wishing to access iOS users have very limited choice

but to use the App Store. Moreover, Apple’s terms of access to the App Store make

the emergence of alternatives highly unlikely.

• Some Android users and app developers wishing to access Android users have

potential alternatives to the Play Store given alternative app marketplaces can be

installed on Android devices. However, these app marketplaces face significant

impediments to attracting users and app developers given the Play Store is commonly