THE ALIGNMENT BETWEEN SELF-REPORTED AND

ADMINISTRATIVE MEASURES OF APPLICATION TO AND RECEIPT OF

FEDERAL DISABILITY BENEFITS IN THE HEALTH AND RETIREMENT STUDY

Jody Schimmel Hyde and Amal Harrati

CRR WP 2021-26

December 2021

Center for Retirement Research at Boston College

Hovey House

140 Commonwealth Avenue

Chestnut Hill, MA 02467

Tel: 617-552-1762 Fax: 617-552-0191

https://crr.bc.edu

Jody Schimmel Hyde is a principal researcher and deputy director at Mathematica’s Center for

Studying Disability Policy. Amal Harrati is a researcher at Mathematica. The research reported

herein was pursuant to a grant from the U.S. Social Security Administration (SSA) funded as

part of the Retirement and Disability Research Consortium. The findings and conclusions

expressed are solely those of the authors and do not represent the views of SSA, any agency of

the federal government, Mathematica Policy Research, or Boston College. Neither the United

States Government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty,

express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy,

completeness, or usefulness of the contents of this report. Reference herein to any specific

commercial product, process or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise

does not necessarily constitute or imply endorsement, recommendation or favoring by the United

States Government or any agency thereof. The authors wish to acknowledge outstanding

programming work by Rachel Hildrich as well as valuable review comments from Purvi Sevak

and Michael Anderson, all of Mathematica. Additionally, this work benefitted from discussions

about the HRS-SSA linkage with David Weir and Chichun Fang at the University of Michigan.

© 2021, Jody Schimmel Hyde and Amal Harrati. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not

to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit,

including © notice, is given to the source.

About the Center for Retirement Research

The Center for Retirement Research at Boston College, part of a consortium that includes

parallel centers at the National Bureau of Economic Research, the University of Michigan, and

the University of Wisconsin-Madison, was established in 1998 through a grant from the U.S.

Social Security Administration. The Center’s mission is to produce first-class research and forge

a strong link between the academic community and decision-makers in the public and private

sectors around an issue of critical importance to the nation’s future. To achieve this mission, the

Center conducts a wide variety of research projects, transmits new findings to a broad audience,

trains new scholars, and broadens access to valuable data sources.

Center for Retirement Research at Boston College

Hovey House

140 Commonwealth Ave

Chestnut Hill, MA 02467

Tel: 617-552-1762 Fax: 617-552-0191

https://crr.bc.edu/

Affiliated Institutions:

The Brookings Institution

Mathematica – Center for Studying Disability Policy

Syracuse University

Urban Institute

Abstract

This paper examines the alignment between self-reported and administrative records of

applications to and receipt of federal disability benefits. It uses data from the Health and

Retirement Study (HRS), specifically the cross-wave consistent version developed by the RAND

Corporation. The HRS has surveyed adults over the age of 50 every other year since 1992 to be

nationally representative of the non-institutionalized older adult population, replenishing the

sample with a new cohort every six years. The HRS asks respondents periodically if they are

willing to have their survey information linked to earnings and benefits information maintained

by the U.S. Social Security Administration (SSA). Most respondents agree to the linkage, which

provides another source of information about application and receipt patterns for Social Security

Disability Insurance (SSDI) and Supplemental Security Income (SSI) than the data that is

collected from respondents in the survey. This information may be valuable in understanding

disability program participation among older workers and the extent to which survey respondents

accurately report their benefit receipt.

Using information in the HRS linked to SSA’s Form 831 records about disability benefit

applications and its Disability Analysis File about benefit receipt, the paper compares survey and

administrative reports of having ever applied to SSDI and SSI as well as the receipt of those

benefits in each HRS survey wave from 1996 through 2016. It presents statistics on the

characteristics of HRS respondents based on whether they consented to have their records linked

to administrative files as well as whether those who consented to the linkage accurately reported

their benefits status. The analyses make comparisons by calendar year and HRS sampling

cohort, as well as by each age from 51 through full retirement age. An appendix to the paper

offers a primer for other researchers considering using the HRS-SSA linked data.

The paper found that:

• Older cohorts in the HRS are more likely than younger ones to have consented to having

their HRS data linked to SSA administrative records. Younger cohorts, however, are

more likely to have consented in recent years, which is necessary to have been included

in HRS’s prospective permission scheme and to have consented to certain file linkages

that may be useful to researchers, including the ones we used in our analysis.

• Aggregate self-reported percentages of application and receipt of SSDI and SSI are lower

than those reported in HRS-SSA administrative data at nearly all ages, but rates of new

applications and receipt of benefits (i.e., incidence) are similar between the ages of

entering the HRS survey (51-56) through SSA’s full retirement age.

• There are differences in SSDI and SSI application and receipt shares between HRS self-

reports and administrative data across birth cohorts in the survey, but no systematic

pattern in the difference between the two sources of information across all of the survey

cohorts.

• Individual misreporting represents a minority of total cases but is more common relative

to the share of older adults with interactions with the SSDI and SSI programs. Misreports

range from approximately 4 percent to 12 percent of total respondents, depending on the

program and age of respondents. False negatives (the respondent reports no application

or receipt while the SSA data indicates application or receipt) tend to be more common

than false positives, especially at older ages.

• The demographic, socioeconomic, and health characteristics of respondents who

incorrectly report their benefits receipt (relative to SSA information) are different from

respondents whose self-reports align with administrative records. Those differences vary

by receipt of SSDI or SSI, but include respondent age, race, income, assets, education,

health conditions, and health behaviors.

The policy implications of the findings are:

• Researchers who use HRS self-report data alone should be aware of differences in the

prevalence rates relative to SSA-published statistics and administrative records for the

same respondents. Using HRS self-reported data is likely to result in an underestimation

of program application and receipt relative to HRS-SSA data. Moreover, characteristics

of those who misreport differ from the full sample, meaning that descriptions of

applicants’ or recipients’ demographics, employment, income, and health may differ

depending on what sample is being used. As such, care should be taken in interpretations

of applicant or beneficiary characteristics when using self-reports.

• Use of the SSA data linkage may not be feasible for all research purposes, particularly

those where a loss in sample size due to consenting to the linkage would be problematic.

In cases where a linkage may not be practical, use of self-responses can still be

informative in many research applications. These can include, but are not limited to,

longitudinal analyses of employment or health characteristics in relation to SSA

programs or the use of receipt or beneficiary status as covariates or controls in analysis.

Introduction

Understanding the circumstances that lead to federal disability benefit application and the

post-application outcomes of both beneficiaries and denied applicants is critically important for

considering changes to the determination process, program rules, or benefit generosity. The

Social Security Administration (SSA) only collects information necessary to make benefit

determinations and administer monthly benefits. As such, SSA collects some information from

applicants about their work history, education, health status, income, and assets, but does not

always know with whom applicants live, their other income sources, and whether they receive

other forms of public or private assistance (SSA 2021). Once receiving benefits, SSA may

periodically collect information on an individual’s health status for the purposes of continuing

disability reviews and will know if participants’ earnings exceed substantial gainful activity, but

the information available to the agency is limited.

For these reasons, researchers and policymakers turn to other sources information

collected from disability program applicants and beneficiaries to have a more comprehensive

understanding of their needs. Many nationally representative surveys collect detailed

information from their respondents, including whether they believe they have a disability, have

applied for Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) or Supplemental Security Income (SSI),

or receive benefits from either program. Many of these sources solely collect self-reported

information from their respondents, but some surveys link information collected from survey

respondents to the SSA’s administrative data to augment self-reported benefits status with the

best information available to the agency. Recent research has capitalized on that linkage to

better understand the accuracy of self-reported survey data, which is critical both in deciding

how much trust to place in self-reports, but also in considering how to combine information from

two potentially differing sources. As we discuss in what follows, the findings vary by the source

of public benefits as well as the survey collecting the data (see for example, Meyer and Mittag

2019; Chen, Munnell, and Sanzenbacher 2018; Bee and Mitchell 2017).

In this manuscript, we compare reports of SSDI and SSI application and receipt using

survey data from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) to similar information contained in

SSA administrative records. The HRS is a nationally representative, longitudinal survey of

noninstitutionalized adults in the United States from age 51 onward that started in 1992; each

respondent is interviewed every other year until they die or otherwise exit the study. As

2

respondents age, the HRS replenishes the survey every six years (in 1998, 2004, 2010, etc.).

During each survey wave, respondents report their own benefits history, but have been

periodically asked to have their information linked to earnings and benefits information stored by

SSA, which administers the federal disability programs. Not all survey respondents consent to

the linkage, but for those who do, it is possible to compare information reported by respondents

to their administrative record to better understand the validity of self-reported benefits status and

the potential utility of the administrative linkage for research purposes.

There are several reasons why making such a comparison with the HRS is important,

even with the extant literature from other survey data sources. First, health shocks occur more

frequently with age (Smith 2003), so HRS respondents will have heightened need for federal

disability benefits relative to younger adults in other national surveys. Second, the years just

before retirement offer what might be a potentially confusing mix of benefits: SSDI is available

through full retirement age, Old Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) benefits become available

at age 62, and SSI benefits span both ages with eligibility requirements that change at age 65.

Thus, misreporting may be more common, particularly given that all three programs are

administered by SSA. Finally, the HRS has been collected since the early 1990s, and since that

time, survey nonresponse has increased (Singer 2006), which could also signal changes in the

quality of information obtained from those who do participate. Understanding how responses to

questions on disability benefits and consenting to the administrative linkage over subsequent

cohorts in the HRS may help researchers select samples and frame questions for future research

studies.

Our descriptive analysis is meant to provide information to HRS users about the accuracy

of self-reported disability benefits collected in the survey and the potential strengths and

limitations of using the matched administrative data. We answer the following questions:

• What share of HRS respondents consented to having their data linked to allow for the

measurement of SSDI and SSI application and receipt? How did the likelihood of

consenting vary by cohort and over time?

3

• How do HRS respondents who consented to the SSA administrative linkage differ from

those who did not, in terms of characteristics and the reporting of SSDI and SSI

application and receipt?

• How do prevalence rates of having applied for or received SSDI or SSDI vary by cohort,

time, and age? How different are the aggregate rates if a researcher were to use the self-

reported data instead of the administrative records, and what factors might explain the

difference?

• Among respondents who consented to the linkage, how accurate are self-reports, and

what do we know about respondents whose reports are incorrect?

We find that a majority of HRS respondents have consented to having their data linked to

SSA records, but rates of consent differ by survey cohort and over time. Consistent with earlier

studies, we find demographic, employment, and health-related characteristics differ between

respondents who do and do not consent to the linkage. We also find that generally, the share of

respondents who report having applied to or receiving SSDI or SSI is lower than SSA records

indicate. The pattern of underreporting is generally consistent across respondent age (regardless

of what cohort or survey year they are asked); however, there is not a consistent pattern across

survey cohorts. As with consenting to a linkage, we find differences in demographic,

socioeconomic and health characteristics for respondents whose self-reports are discordant from

their administrative records as compared to those who do not misreport.

In addition to documenting the alignment between self-reports and administrative

records, this manuscript contains a primer for other researchers interested in using the HRS

linked administrative records (Appendix A). While the SSA linkage has been available for more

than two decades, using it requires detailed knowledge of the administrative files and the HRS

process for collecting consent from survey respondents to link their data. With these high

barriers to entry, the SSA linkage has potentially been underutilized. Our hope is that the

manuscript combined with the primer will facilitate use by a broader array of researchers,

particularly for research projects where the richness of the administrative data opens up new

research possibilities to understand longitudinal outcomes of disability applicants and

beneficiaries.

4

Background: The Accuracy of Self-Reported Public Benefits in National Surveys

Surveys offer a depth of information not available in administrative sources alone. This

is especially true for longitudinal surveys, which can provide a detailed look at the

characteristics, outcomes, and trajectories of individuals before, during, and after they apply for

or receive SSDI or SSI. Davies and Fisher (2009) document some of the potential uses of linked

survey and SSA administrative data, while also offering a succinct assessment of earlier work by

researchers including Hyunh et al. (2002) and Koenig (2003) to document the reporting of SSDI

and SSI in survey versus administrative sources. They summarize the literature based on

analysis of data from older adults in the 1990s as showing that respondents to the Current

Population Study (CPS) slightly underreported OASDI and significantly underreported SSI

benefits, while the Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) slightly overreported

OASDI income and was mixed on SSI. Schimmel Hyde et al. (2018) used 2008-2009 data from

the same sources and a working-age population and found that relative to the administrative

record, many beneficiaries misreported their benefits status and income from benefits, and that

discrepancies appeared to be larger than in earlier years of the surveys.

Recent research has sought to augment self-reports in surveys to understand the income

from public benefits more broadly. Beginning with Meyer et al. (2015), together they suggest

that misreporting is not uncommon and errs toward underreporting rather than overreporting.

Meyer and Mittag (2019) found that income from public programs among working-age

respondents in the CPS were dramatically understated in the CPS. Bee and Mitchell (2017)

similarly documented underreporting of income among older adults in the CPS, driven primarily

by misreported defined benefit pensions and retirement account withdrawals. Chen et al. (2018)

extended the Bee and Mitchell work to other data sources and found that the CPS was an outlier

in terms of retirement income misreporting. Compared to capturing 61 percent of retirement

income in the CPS, the SIPP, for example, captured 93 percent of retirement income relative to

administrative data, while the HRS captured 96 percent.

Despite the linkage to SSA administrative data for two decades, to our knowledge, there

has not been work to date to understand the accuracy of reports from HRS respondents about

applications to and receipt of SSDI and SSI. Our paper compared self-reports to administrative

records. While it is simplest to assume that deviations between the two sources reflect

respondent misreporting, it is important to note that there are reasons that individual reports may

5

offer more current or complete information than the administrative records. We will discuss

reasons for deviations in what follows, in part to couch our findings, but also so that other

researchers can use assess the strengths and limitations of self-reports relative to administrative

data based on the research question at hand.

Data and Measures

In this section, we describe the data sources in more detail, the sample cohorts that we

include in our analysis, and the measures we use to document SSDI and SSI application and

receipt. We also discuss the process to collect consent for the administrative linkage from HRS

respondents, implications for sample size, and our approach for adjusting the sample weights to

account for non-consenters.

Data Sources

We combine information from publicly available survey data from the HRS with

restricted-access SSA administrative records. The latter are available with permission from the

HRS following an in-depth application and review process. We focus on a high-level discussion

of the four sources of data we use in our analysis here; more detailed information about the files

and the construction of our measures is contained in Appendix A.

The RAND-HRS is a cross-wave consistent file of the HRS, developed to facilitate

research. The HRS is a longitudinal survey that is nationally-representative of the

noninstitutionalized population in the United States over the age of 50. It has been fielded

biennially since its introduction in 1992. The survey is known for its richness of data on health,

income, retirement, and other topics important to older adults. The RAND-HRS simplifies

information collected about SSI and SSDI benefits over many years of the study and using

different survey instrument design, but is solely based on respondent self-reports in the HRS.

For our analysis, we use the version of the file that contained data through 2018.

Form 831 Respondent Records is an SSA administrative file that contains information on

initial applications for SSDI and SSI. The file we use contained data from 1988 (when SSA

began storing the information) through 2016. Form 831 records are limited to initial applications

that received a medical review and do not include initial applications that were denied because

they did not meet the financial criteria of federal disability programs, nor appealed applications.

6

The Disability Analysis File (DAF) is an SSA file that combines data from multiple

administrative sources to produce monthly information about the receipt of SSDI and SSI

benefits starting in 1996. The version of the file we use contained data through 2018.

The HRS-SSA Permissions Consent History is a file available from HRS that provides

information about whether a respondent to the HRS consented to having their information linked

to SSA records and whether a match with the data was found. We use this file to determine

which respondents might have information available on disability program participation in the

administrative records.

Sample Selection

To align with the availability of administrative records, we use data from 1996 through

2016, spanning four cohorts of the HRS. The cohorts include the HRS cohort (first interviewed

in 1992; birth years 1931-1941), War Baby Cohort (first interviewed in 1998; birth years 1942-

1947), Early Baby Boomers (first interviewed in 2004; born 1948-1953), and Middle Baby

Boomers (first interviewed in 2010; born 1954-1959).

1

We include age-eligible sample members

in each cohort, meaning that younger spouses who were interviewed with an older age-eligible

respondent are included in our analysis once they themselves age into the survey. Except for the

initial HRS cohort, these cohorts were first interviewed when they were ages 51-56. The HRS

cohort included more birth years than the others; for parallel construction with the other later

cohorts, we include only the “young HRS” born in 1936-1941 and first interviewed at ages 51-56

in 1992. We refer to this as the HRS cohort in what follows for simplicity; it is important to note

that we found that the younger and older birth years of the HRS cohort differed in the outcomes

considered in this manuscript.

For three of the cohorts, we use the data collected every other year from the initial

interview through 2016 (Table 1). The exception is the HRS cohort, which initially was

surveyed in 1992, but we do not include in our analysis until 1996, to align with the availability

of data on disability receipt from the DAF. Once the individual reaches SSA’s full retirement

1

The Late Baby Boomers (born 1960-1965) were first interviewed in 2016, but we exclude them from our analysis

because they only had one wave of data during our analysis.

7

age, we no longer measure their SSDI or SSI status.

2

For the birth years in our analysis, SSA was

gradually increasing the FRA from 65 to 66; it was under age 66 for those born before 1943

(increasing by 2 months from 65 to 665 gradually), exactly 66 years for those born from 1943

through 1954, then again increasing gradually to age 67 for those born later. In our cohort

analysis, we categorize respondents in each wave into four groups (1) interviewed, (2) not

interviewed (but alive), (3) dead (but not yet FRA), and (4) interviewed, but reached FRA.

2

At FRA, SSDI benefits convert to Social Security retirement benefits automatically. SSI benefits transition from

disability to old age at age 65, but for purposes of aligning the cohorts, we counted them through FRA; we discuss

the implications of this decision in the results section.

8

Table 1. Timing of HRS Cohort Entry and Interview Waves Used in Analysis

HRS Survey Wave

Birth year

1992

1994

1996

1998

2000

2002

2004

2006

2008

2010

2012

2014

2016

HRS

1936-1937

X

57-58

59-60

61-62

63-64

65-66

1938-1939

X

55-56

57-58

59-60

61-62

63-64

65-66

1940-1941

X

53-54

55-56

57-58

59-60

61-62

63-64

65-66

War Baby

1942-1943

X

57-58

59-60

61-62

63-64

65-66

1944-1945

X

55-56

57-58

59-60

61-62

63-64

65-66

1946-1947

X

53-54

55-56

57-58

59-60

61-62

63-64

65-66

Early Baby Boomer

1948-1949

X

57-58

59-60

61-62

63-64

65-66

1950-1951

X

55-56

57-58

59-60

61-62

63-64

65-66

1952-1953

X

53-54

55-56

57-58

59-60

61-62

63-64

Middle Baby Boomer

1954-1955

X

57-58

59-60

61-62

1956-1957

X

55-56

57-58

59-60

1958-1959

X

53-54

55-56

57-58

Note: X indicates the first wave the cohort was interviewed by the HRS, at ages from 51-56. Shaded cells indicate the survey waves from which we used data

from each cohort. The value shown in each cell is the approximate age range of the birth cohort during the survey wave.

9

HRS Consent Requirements and Implications for Sample Selection

The SSA administrative linkage to the HRS is only available for respondents who

consented to having their records linked and who provided the requisite information to facilitate

a linkage (accurate Social Security number, name, date of birth, and gender). The consent

process has changed over the years of the HRS, as described in more detail in Appendix A.

Importantly for our analysis, the SSA 831 files and DAF are available only for respondents who

consented to the linkage in 2006 or later, meaning that earlier cohorts had the opportunity to

initially consent, but may not have provided the requisite permissions to be in our analysis of

administrative data.

Table 2 shows the full unweighted sample size for each cohort in our analysis, as well as

the share of each cohort who consented to the linkage to SSA benefits data, ever and in 2006 or

later. Over time, the share of each cohort consenting to any linkage has declined, from 88.0

percent in the HRS cohort down to 78.6 percent of Middle Baby Boomers. Despite the declining

rate of consent, the rate of consenting in 2006 or later increases across the cohorts, from 49.0

percent among the HRS cohort to 77.4 percent of the Middle Baby Boomers. The lower rate in

earlier cohorts reflects the fact that those cohorts had a longer elapsed time from survey entry

through 2006, over which many of the respondents left the sample, died, or did not reconsent. In

what follows, we refer to sample that consented in 2006 or later the “consenter sample” for ease

of terminology, noting that this excludes those who consented in an earlier year. Appendix

Table B.1 provides more detail on the interview and consent status of each cohort by birth year

and HRS wave.

Table 2. Sample Size of Each HRS Cohort, by Consent Status

Number of

respondents

Never

consented

Consented

pre-2006

a

Consented

2006 or later

Share ever

consenting

to linkage

Share with

2006 or later

consent

HRS

5,604

670

2,186

2,748

88.0

49.0

War Baby

3,090

473

656

1,961

84.7

63.5

Early Baby Boomer

3,369

578

449

2,342

82.8

69.5

Middle Baby Boomer

4,782

1,019

59

3,703

78.6

77.4

a

Some of the sample members in the Early Boomer and Middle Boomer cohorts were initially interviewed as

younger spouses of respondents in earlier cohorts. We included these respondents based on their own birth year

cohort, but they were able to provide consent to the linkage before their birth year entry cohort while in the same as

an age-ineligible spouse.

Source: Authors’ calculations using the RAND-HRS and SSA data linkage. Sample sizes are based the age-eligible

cohort at survey entry year and do not include age-ineligible spouses or spouses added in subsequent survey waves.

10

Consistent with earlier work (HRS, March 2021), we found that the consenter sample has

different characteristics than the full HRS sample (Appendix Table B.2). In brief, we find that

respondents who consent to linkage are more likely to be white, female, and employed, have

higher education, longer work histories, and lower rates of chronic conditions including heart

disease, lung disease, diabetes, and stroke. Consenters report lower rates of smoking and

drinking, fewer difficulties with activities of daily living (ADLs) and fewer hospital stays and

doctor’s visits.

Weighting

Because of the differences in the sample size and composition between those that consent

and the full HRS sample, simply using the administrative linkage with the HRS survey weights

will not produce nationally representative estimates. To adjust the sample weights, we predicted

the likelihood of consenting in 2006 or later using a logistic regression in each survey wave

following a process that the HRS uses. Our model included sex, race and ethnicity (indicators

for Black and Hispanic), marital status (indicators for married, divorced, and widowed),

education (indicators for high school graduate, some college, college graduate or advanced

degree), an indicator for being employed, categories of self-rated health status, and quintiles of

household income and wealth.

3

We used the predicted values from the logistic regression models to generate inverse

probability weights (IPW), which we then applied along with the HRS sampling weights to the

consenter sample. Applying the IPW in each wave to the survey weights yields a weighted sum

of interviewed consenters in each wave that equals the weighted sample size of interviewed

respondents that wave from the full HRS.

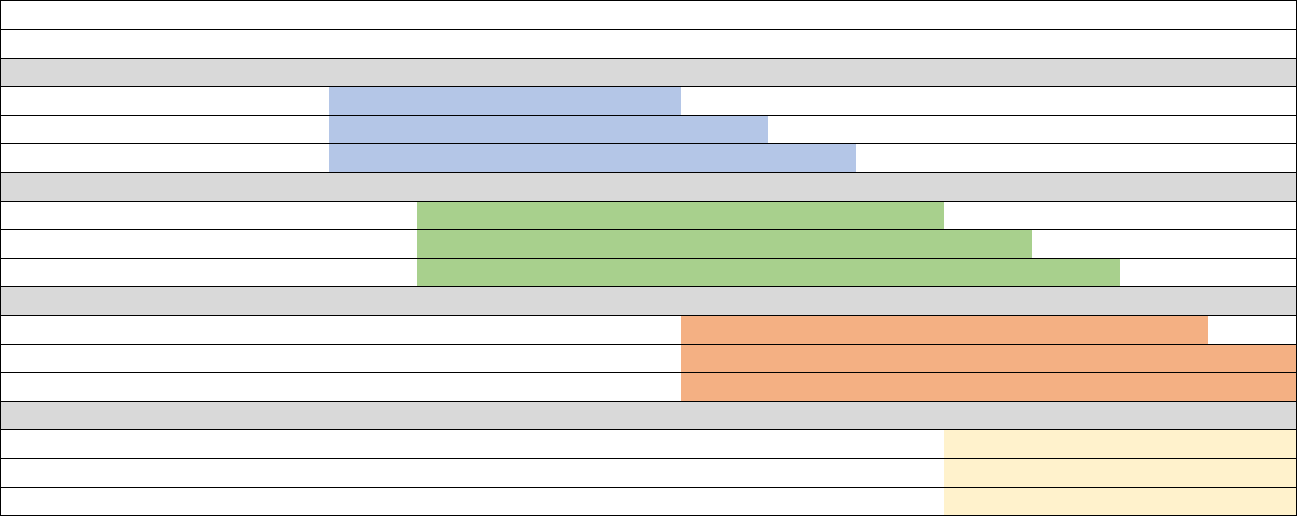

Figure 1 shows the weighted distribution of each cohort and wave, from the year of

entering the survey through 2016, applying the wave-specific IPW to the baseline weights for

each cohort. In the figure, gray bar shows the number interviewed in each wave who had the

necessary consent to be in the SSA administrative files we use. The IPW reweighting process

for analyzing the administrative data means that the weighted sum of the consenter sample (gray

3

We used the same characteristics to predict the likelihood of consenting in 2006 or later as the HRS uses to

construct its wave-specific weights for working with the SSA data. In our case, we needed to modify their process

for some of the analyses that follow and could not solely rely on the weights they developed consents. We used

cross-wave consistent measures of the included variables from the RAND-HRS file.

11

portion of the bar) equals the weighted sum of the total number interviewed in each wave (the

combination of the light blue, orange, and gray bars). Over time, the share of the sample that is

interviewed falls due to attrition or death. The full HRS and War Baby cohorts reach FRA

before 2016, while only part of the Early Baby Boomers do (and none of the Middle Baby

Boomers). Because two-year birth cohorts attain FRA over multiple survey waves, it is

important to note compositional changes in the “cohort” included in our analysis in the years

approaching FRA, as shown in Table 1.

12

Figure 1. Interview and Consent Status of Each HRS Cohort from 1992 through 2016

Notes: Values are weighted using the HRS sampling weight from the baseline interview in each cohort. Analogous unweighted values are contained in Appendix

Table B.1.

Source: Authors’ calculations using the RAND-HRS and SSA data linkage.

13

Measuring SSDI and SSI Application and Receipt

In this section, we describe our approach to measuring applications to and receipt of

SSDI and SSI; more details are contained in Appendix A. Self-reported values are defined using

cross-wave consistent measures in the RAND-HRS file. Administrative information on

applications came from SSA’s Form 831 records, as linked to the HRS, while administrative

records on benefit receipt were derived from the DAF. If an HRS respondent consented to the

SSA linkage but did not have information available in the 831 file for either SSDI or SSI, we

assume they had not applied for benefits. We follow a similar approach if they consented to the

administrative linkage but did not have a record in the DAF, coding the respondent as a non-

beneficiary (for the relevant program).

Application. For self-reported applications, we use the spell data available in the RAND-

HRS to identify whether the person had ever reported applying for SSDI and/or SSI by the date

of the HRS interview. We measure applications in SSA administrative records using Form 831

records, which contain information on initial disability applications from 1988 onward. For both

the self-reports and administrative data, we assume that if the respondent is a beneficiary (based

on the comparable self-report or administrative measure), that they applied for the program at

some point in the past, even if the application data do not indicate that to be the case. This is

especially important in the administrative data because the 831 records began in 1988. It is

therefore quite likely that sample members in the older cohorts might have applied for and begun

to receive benefits before that time; we would observe them as receiving benefits but might not

find their application in the 831 files. It is also possible that HRS respondents may have

neglected to provide complete application data for spells that began long before their first HRS

interview, despite accurately reporting current receipt data.

As described in more detail in Appendix A, there are reasons why individual self-reports

of applications may not align to administrative records. Most importantly, the 831 records likely

undercount what individuals themselves would report, because the former only contain

applications that have received an initial determination following a complete medical review by

SSA’s Disability Determination Services offices. The 831 file does not include (1) applications

that have not yet received an initial determination, (2) applications denied on the basis of not

meeting the program’s financial criteria, and (3) applications being appealed beyond the initial

and reconsideration levels. Based on the questions in the HRS, all three of these scenarios would

14

be reported as an application by respondents. It is also possible that the 831 file contains

applications that respondents may not report; for example, a respondent who applies for SSI may

not know that SSA will also process an application for SSDI if eligible.

Benefit Receipt. We measured the receipt of SSDI and SSI at time of the HRS interview.

For self-reports, we used wave-specific measures in the RAND-HRS indicating that the

respondent was currently receiving benefits from SSDI and/or SSI. We measured the receipt of

benefits based on SSA administrative records using the DAF. We measured benefit receipt in

the DAF based on beneficiaries being in current payment status in the month(s) of the HRS

interview.

4

One important consideration in our measures of benefit receipt is that the HRS question

wording in the earlier years allowed for uncertainty in program participation in a way that did not

occur in later waves. From 1992 through 2000, respondents were asked about SSDI and SSI

together. Where possible, information collected from respondents after 2000 was subsequently

used to “backfill” records by RAND in the cross-wave consistent measures in the RAND-HRS

for each program (e.g. replacing “SSDI or SSI” with “SSDI but not SSI” based on later reports).

It was not possible in all cases (for example, if a respondent died or left the sample), and prior to

2000, so a fair amount of uncertainty remains about the program under which respondents

applied for or received benefits. After 2000, the survey questions on disability benefit receipt

were separated by program.

To be the most consistent across time, we opted for a “narrow” measure in which we did

not account for application/receipt from an unknown program, limiting our applicants and

beneficiaries only to those for whom definitive information about the program was available.

(For example, respondents who did not ever clarify whether they received benefits from SSDI or

SSI were classified as not being beneficiaries.) Based on our review of patterns over time, the

narrow measure we use likely understates program participation before 2000.

5

4

In cases where the HRS interview spanned multiple months, we looked for benefit receipt in any of those months

in the administrative data.

5

In the earliest years of the survey (1992 and 1994), many of the application and receipt reports were not reconciled.

SSDI application and receipt prevalence rates that included the unknown program category were 2-3 times higher

than those we report, and SSI application and receipt rates that were 7-10 times higher. The magnitude of the

difference got smaller in each year through 2000, presumably reflecting a higher likelihood of reinterviewing

respondents in 2000 or later that allowed for the record to be updated.

15

Profiles of SSDI and SSI Application and Receipt by Time and Cohort

To start, we consider the aggregate alignment of survey and administrative reports in

each year, incorporating all four of our cohorts. In general, self-reported applications to and

receipt of SSDI and SSI are lower than comparable administrative reports. However, the rates of

new applications and receipt over time are quite similar. Figure 2 shows the profile of each of

the four measures of interest in each HRS interview year from 1996 through 2016 for the cohorts

included in our analysis. The black line shows self-reports, while the gray line shows

administrative values, where both have been weighted to be nationally representative; the former

using HRS sampling weights and the latter using the IPW method above to reweight the

consenter sample to the same overall population size.

Starting with SSDI, we see that both self-reported and administrative measures of receipt

generally increase over the period. Self-reported values of receipt are always lower than the

measure using administrative data at the same time, with the former increasing from about 2

percent in 1996 to just under 10 percent in 2016 and the latter increasing from 7 percent to just

over 10 percent over the same period. The share who had ever applied for SSDI at each point is

lower based on self-reports than administrative records through 2004, almost identical through

2008, after which the self-reports are higher than administrative values. Self-reports start with

around 4 percent reporting having applied for SSDI in 1996 and rise to 16 percent by 2016, while

administrative records show about 8 percent had applied by 1996 and 14 percent by 2016. The

patterns over time are consistent with increasing SSDI receipt over the period, though the

addition of new, younger cohorts in 1998, 2004 and 2010 obscure some of the patterns of the

aging of the earlier cohorts. The youngest cohort was 51-56 in 2010 and had aged 6 years by the

last year, showing an application and receipt pattern consistent with increased SSDI receipt with

age.

Despite level differences in SSDI receipt and application in self-reports and

administrative data, both sources show similar patterns in new receipt and applications over the

period. The slopes of the lines measure new receipt and/or application and are therefore

analogous to incidence of program application or participation. The slopes of the lines for SSDI

receipt are relatively similar at most points after 2000 (when the HRS began asking separate

questions about SSDI and SSI), except for the period during the Great Recession, where the

16

administrative values had more marked changes than self-reports. After 2000, the slopes are

quite similar for SSDI applications as well.

In general, self-reported values of applications and receipt of SSI are also lower than

administrative data, though the difference between the two are more modest than for SSDI,

especially after 2000. As mentioned above, prior to 2000, the HRS queried respondents about

SSDI and SSI in the same question, with the RAND-HRS separating responses where possible

later. Because we only accounted for known program status, and the SSI values are substantially

lower using that measure than one that accounts for uncertainty (not shown). After 2000, the

difference between self-reported and administrative values were relatively modest, fluctuating

between 2 and 2.5 percent in each year. The share of respondents who had ever applied for SSI

increased from 0.5 percent in 1996 to almost 8 percent by 2016 based on self-reports compared

with a change from 4.5 to nearly 10 percent based on administrative values.

17

Figure 2. SSDI and SSI Application and Receipt in HRS Survey Waves from 1996 through 2016

Notes: Limited to respondents born from 1936 through 1959 and part of the HRS, War Baby, and Early and Middle Boomer cohorts of the HRS. Values are

weighted to produce nationally representative estimates in the year, as described in the text.

Source: Authors’ calculations using the RAND-HRS and SSA data linkage.

18

The annual values in Figure 2 combine patterns over time based on secular patterns in

experience with federal disability programs, differences in patterns across HRS cohorts

(reflecting a range of factors including labor market conditions experienced by each cohort and

sufficient labor force participation to be insured for SSDI), as well as aging of cohorts in the

HRS as they are followed over time. We next disaggregate the data shown in Figure 2 to

highlight differences in self-reported and administrative values for each cohort in our analysis.

Figure 3 highlights the same four outcome measures, but the horizontal axis has been reoriented

from calendar time to the wave of the HRS interview relative to the first interview for each of

four cohorts. As shown in Table 1, the HRS cohort was first interviewed in 1992, the War Baby

cohort in 1998, the Early Baby Boomers in 2004 and the Late Baby Boomers in 2010. In each

case, that wave is “wave 1” in Figure 3; the HRS cohort therefore does not have data until wave

3 which occurred in 1996 when the DAF data began.

In Figure 3, the solid line for each cohort represents the self-reported value in the wave

relative to sample entry, while the dashed line of the same color represents the value from the

administrative data. The figure does not show that there are strong patterns by cohort across all

four measures, either comparing across cohorts or comparing self-reports to administrative

records. More recent cohorts tend to overstate their receipt of SSDI relative to administrative

records, aligning with the pattern shown in Figure 2 where self-reported receipt exceeds the

administrative record in the later years of our analysis period. Patterns are less clear for SSDI

application or the SSI measures. One pattern for SSI receipt is a product of our sample

definition: we include respondents through FRA but the SSI program after age 65 reflects old-

age benefits; this may explain the declining SSI receipt among self-reports in the last waves for

the cohorts that reach FRA. Those cohorts also may be misreporting SSI as OASI at those

points, though we did not explore that possibility.

Maestas et al. (2015) found increased SSDI participation during and following the Great

Recession of 2008; we would expect to see this primarily in 2010 given the HRS survey timing.

This corresponds to Wave 7 for the War Baby Cohort and Wave 4 of the Early Baby Boomers.

We do not see notable deviations from the previous trend in SSDI or SSI application or receipt at

that point for those cohorts, either in the self-reported or administrative data. By wave 7 of the

War Baby cohort, much of the sample had passed the earliest age of retirement at 62, so it may

be that the cohort claimed OASI early and did not meet the criteria for SSDI.

19

Figure 3. SSDI and SSI Application and Receipt for each HRS Cohort from Entry through FRA or 2016

Notes: Limited to respondents born from 1936 through 1959 and part of the HRS, War Baby, and Early and Middle Boomer cohorts of the HRS. Values are

weighted to produce nationally representative estimates in the year, as described in the text.

Source: Authors’ calculations using the RAND-HRS and SSA data linkage.

20

Age Profiles of SSDI and SSI Application and Receipt

Next, we examine reporting of SSDI and SSI applications and benefits by age. To do

this, we reoriented the data collected across many years, such that all respondents are “stacked”

by the same age (i.e., 51-52, 53-54, etc.),

6

regardless of the corresponding data wave. This

structure allows direct comparisons by age but does not consider compositional effects of cohorts

or time. These results are weighted using our IPW method described above but run by age

interval rather than by wave. We then apply the IPW to the wave weight available in the RAND-

HRS for the respondent at the relevant age. These estimated are therefore nationally

representative of the age group across all of the survey years.

Figure 4 displays the percentage of respondents who self-reported SSDI and SSI

application and/or receipt alongside corresponding percentages from SSA administrative records.

We show values at each age and interpret these values as a measure of wave-specific prevalence

of having applied to or receiving benefits. It is important to note that not all the HRS cohorts

have data at each of the ages; the values shown include all of the respondents at each age who

had data available. Table 1 highlights the years from which we identified respondents of a

particular age and cohort. For example, 51-to-54-year-olds are not included from the HRS

cohort because they were interviewed in 1992 and 1994, but our analysis begins in 1996. On the

other end of the age range, the Middle Boomers were last interviewed when ages 57-62. We

include the information we have available at each age, meaning that these analyses are not for

cohorts across the full age range we consider.

We report SSDI and SSI separately by program and also combined across programs. The

combined measure is designed to account for individuals who may know they have interacted

with a disability program administered by SSA but may incorrectly recall the program. If

misreporting reflects confusion of the program reported, we would expect this combined

measure to more closely align with SSA records than either of the individual program measures.

The top bar, in blue, corresponds to self-reports from the full HRS sample; this is the

value that users without access to the administrative linkage would report. The gray bar reflects

6

Note that the “age” we use is based on HRS survey wave and birth year, rather than actual age at interview, to

avoid issues with birth dates and HRS interviews that are not necessarily exactly two years apart. For example, a

respondent with a birth year of May 15, 1947, might have been 53 when interviewed by the HRS on May 31, 2000.

Yet when interviewed again on April 1, 2002, would only be 54. We would classify this respondent in the 53-54

age bin in 2000 and the 55-56 age bin in 2002.

21

the corresponding reports in the SSA administrative data, limited only to consenters. The blue

and gray bars mirror information reported by cohort and year earlier, simply transformed to

report by age instead. The middle orange bar represents self-reports from the HRS but is limited

to those who consented to SSA administrative linkage. The purpose of adding this bar is to

consider how different self-reports are among consenters relative to the full HRS sample

(comparing the blue and orange bars) and how different self-reports among consenters are from

their administrative linkage (comparing the orange and gray bars).

Figure 4 confirms again that HRS self-reports are generally lower than administrative

records for both the full sample and the subset who have consented to a data linkage. This is true

for SSDI receipt and SSI application and receipt (with the exception of SSI receipt at age 65 and

older).

7

In the case of SSDI applications, self-reports are higher than the administrative records

until age 60, after which the pattern switches. Despite finding that that respondents who consent

to the SSA data linkage differ on a number of demographic and health characteristics, the

aggregate patterns of reporting on application and receipt do not differ substantially between

consenters and the full HRS sample.

There is not a significant age gradient in the observed gaps between self-reports and

administrative reports; we expected we might see substantially more misreporting after age 62

when respondents could claim Social Security retirement benefits. There is modest evidence that

misreporting of benefits increases as respondents reach the earliest age of eligibility for Social

Security retirement benefits at age 62. For example, self-reports and administrative measures of

SSDI are much closer at ages 55-56 than at 63-64. Yet, we do not observe a similar pattern for

SSI, nor do we see that the combination of SSDI and SSI produces values that are substantially

closer across self-reports and administrative values. It is important to note that because the

composition of the sample is changing with age given the availability of data at older ages for

more recent cohorts, we cannot definitively conclude that self-reports at older ages reflect (or do

not reflect) confusion over the program from which benefits are being claimed.

7

The pattern at age 65-66 for SSI should be interpreted with caution; the SSI program after age 65 may be for old

age benefits rather than for disability. For consistency’s sake and to align with the DAF STW measure, we used this

value through full-retirement age, but there are reasons to think this comparison may reflect a different set of

considerations than at younger ages.

22

Figure 4. Comparisons of Percentage of SSDI and SSI Application and Receipt, by Age

23

Figure 4. Comparisons of Percentage of SSDI and SSI Application and Receipt, by Age (cont’d)

Notes: Limited to respondents born from 1936 through 1959 and part of the HRS, War Baby, and Early and Middle

Boomer cohorts of the HRS. Values are weighted to produce nationally representative estimates at each age, as

described in the text. SSDI or SSI refers to the total number of respondents who report either program; some

respondents report only one program and some report to both.

Source: Authors’ calculations using the RAND-HRS and SSA data linkage.

24

The Individual Accuracy of Self-Reported Responses About SSDI and SSI Application and

Receipt

Having described patterns of reporting in the aggregate—by wave, cohort, and age—we

now turn to describing the accuracy of individual self-reports. We focus on two age groups, 55

years old, the age at which there are likely to be the greatest number of respondents with data,

and 63, prior to FRA. For both SSDI and SSI, we categorize reporting into one of four groups.

Correct negative means that a respondent reports not having applied for or is receiving SSDI (or

SSI) and the corresponding administrative record concurs. Likewise, correct positive means a

concurrence in self-reports and administrative data for respondents who have applied or received

benefits. A false positive misreport indicates that a respondent indicates they have applied or are

receiving benefits whereas administrative records do not indicate application or receipt. Finally,

a false negative misreport is the opposite—respondents report no application or receipt and

administrative data does record an application or receipt. We report all data on misreports

without using sampling weights; we are interested in the likelihood of misreporting by groups of

respondents and therefore nationally representative estimates are not appropriate in this context.

Figure 5 displays the distribution of reports for SSDI and SSI applications, at age 55 and

63, by their accuracy. The blue segment of each bar correct negatives. Because a minority

interact with disability programs, this segment of the bar is the largest, representing 85 to 90

percent of all respondents. The orange segment of the bar represents correct positives; this

segment is far smaller than the blue bar simply because relatively few older adults receive

benefits. The gray and yellow segments of the bars show false positives and false negatives,

respectively. Together, these bars represent the share who misreport their benefits, which is

small relative to the full sample; 7-8 percent of HRS respondents misreport SSDI applications.

25

Figure 5. The Accuracy of Self-reported SSDI and SSI Applications at Ages 55 and 63

Notes: Limited to respondents born from 1936 through 1959 and part of the HRS, War Baby, and Early and Middle

Boomer cohorts of the HRS. Values are unweighted. “SSDI/SSI” refers to the total number of respondents who

report either program; some respondents report only one program and some report to both.

Source: Authors’ calculations using the RAND-HRS and SSA data linkage.

Another way to consider the magnitude of misreporting is to consider false reports as a

share of total reports within a given category. This allows for a much closer inspection of the

effect of misreporting on aggregate values. For example, consider SSDI applications at age 63

(Figure 5), where 18.6 percent of the total respondents with a self-report or administrative record

indicated an application. The share of false positives (3.9 percent) is close to the share of false

negatives (4.7 percent), yet false negatives represent a lower share of the total negatives than

false positives relative to total positives. This means that positive self-reports are more likely to

be wrong relative to the administrative record; 26.4 percent of positive self-reports were

incorrect (3.9 of 14.8 percent) compared to only 5.5 percent of negative self-reports (4.7 of 85.2

26

percent). Other than SSDI applications at age 55, the share of reports that is false negative is

larger than share that is false positive.

Figure 6 displays similar results for the receipt of benefits at ages 55 and 63, with similar

patterns. Overall, correct negatives are the largest share of reports, consistent with disability

program participation. While misreports are a small share of the total, they are much larger

when compared to total positive reports. Again, we see that for these outcomes, false negatives

are more common than false positives.

It is helpful to compare the distributions in Figures 5 and 6 to the total misreports in

Figure 4. In Figure 6, the percentage of receipt of a program is the sum of correct positives and

false negatives. For example, the percent of respondents receiving SSDI at age 55 from Figure 6

is 7.1 percent—5.1 percent (correct positives) plus 2.0 percent (false positives). The equivalent

value in Figure 4 is represented by the orange bar, self-report for those who consent to a linkage

and therefore have a corresponding administrative record from which we can assess

misreporting. In this case, the percent of 55-year-olds with an SSDI application is 6.4 percent.

Because the values in Figure 4 are weighted and those in Figures 5 and 6 are not, we expect these

values to be similar—as they are—but not necessarily identical.

27

Figure 6. The Accuracy of Self-reported SSDI and SSI Receipt at Ages 55 and 63

Notes: Limited to respondents born from 1936 through 1959 and part of the HRS, War Baby, and Early and Middle

Boomer cohorts of the HRS. Values are unweighted. “SSDI/SSI” refers to the total number of respondents who

report either program; some respondents report only one program and some report to both.

Source: Authors’ calculations using the RAND-HRS and SSA data linkage.

We sought to understand the characteristics of respondents who misreported, to assess

whether misreporting is concentrated in particular subgroups. In Tables 3a and 3b, we examine

selected differences in demographic and health characteristics for respondents who misreported

the receipt of benefits. We focus on receipt of benefits simply to avoid a vast number of

comparisons; results from a similar analysis for application are available upon request. In Table

3a, we compare differences between the false positive group relative to the correct positive

group. In Table 3b, we compare differences between the false negative group and correct

negative group.

These tables contain several simplifications to aid in interpretation. First, we limit to

characteristics in which we identified statistically significant differences between those who

28

report correctly versus those who misreport in at least one of the outcomes we considered. To

simplify the presentation further, we focus on groups of variables (e.g., race includes white,

Black and other where we tested the difference in the racial distribution of the groups). A check

in the box indicates that the mean or distribution of the variable category shown was statistically

different across the two groups. Appendix Tables B.3 and B.4 contain full results of these

comparisons.

Starting with Table 3a, we find that there are differences between those who misreported

that they were receiving benefits (false positives) relative to those who correctly reported they

were receiving benefits (correct positives). We do not observe consistent patterns in the

characteristics correlated with misreporting across program or age. For 55-year-olds,

misreporters of SSDI receipt differed from correct reporters by race, gender, marital status,

educational attainment of respondents. Those with false positive reports for SSDI at age 55 were

also more likely to report poorer health (with higher prevalence of high blood pressure and a

higher self-reported probability of having a work-limiting health condition in the next ten years)

and had worked for fewer years. At age 63, respondents with false positive for SSDI receipt

were twice as likely to be Hispanic, had an average of nearly one less year of education, had an

average of four less years of employment over their lifetimes, and scored higher on the CESD

mental health test.

We also observe demographic and health differences for false positive reports among 55-

year-olds relative to correct positives for SSI, but they are not the same characteristics as for

SSDI. SSI misreporters differ from correct reporters on race and ethnicity, as well as on average

income and assets. Notably, false positive reporters are more likely to have higher incomes and

assets (which might be expected, given the income and assets limits for SSI). There are also

health differences between false and correct positives; those with false positive reports tend to

have better health behaviors but report worse health. Those with false positive reports are less

likely to be smokers, report drinking fewer alcohol drinks per day, are less likely to report having

a psychological problem, have had more hospital stays in the last two years, and have higher out-

of-pocket medical expenditures. In general, the patterns of differences in misreporting SSI at age

63 reflect a different set of characteristics than at age 55.

Table 3b reveals that there are consistent differences between false negative and correct

negative reporters, across age and program. In fact, we find that there are statistically significant

29

differences across most individual characteristics. This pattern may not be particularly

surprising for two reasons. The first is sample size; correct negatives include all respondents that

have no program interaction with SSDI or SSI, which as shown in Figure 6, is the majority of the

sample. As such, sample sizes may be better powered to detect statistically significant

differences in characteristics. The second is the underlying truth in program participation. False

negative reporters are those actually receiving benefits and therefore meeting the financial and

health characteristics of the program. Because beneficiaries have significant health and

functional impairments and are generally out of the labor force, the differences in socioeconomic

and health characteristics are to be expected.

30

Table 3a. Differences in Demographic and Health Characteristics among Those Reporting

Benefit Receipt (check mark shows statistically significant differences between false positives

and correct positives

1

)

Age 55 receipt status

Age 63 receipt status

SSDI

SSI

SSDI

SSI

Demographic characteristics

Race

Ethnicity

Gender

Marital status

Socioeconomic characteristics and employment

Education (years)

Income

Assets

Working for pay

Self-reported probability of work-limiting

health condition in ten years

Total number of years worked

Health characteristics and behaviors

Has high blood pressure

Has lung disease

Has psychiatric problems

Current smoker

Number of alcoholic drinks per day

Body mass index (above 30 indicates

obesity)

CESD mental health score

2

Number of hospital stays in two years

Have visited the doctor in two years

Out of pocket medical expenditures

N (Correct positives)

437

156

492

95

N (False positives)

173

79

144

60

1

We used a t-test to compare the difference in means and a chi-square test to assess the difference in distributions.

When we tested the distribution, the test statistic is shown for the category heading.

2

Depressive symptoms measured by the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression (CESD), an 8-point battery.

Notes: All values are taken at the ages 55 or 63, respectively, and all dollar values are inflated-adjusted to 2020

dollars.

Source: Authors’ calculations using the RAND-HRS and SSA data linkage.

31

Table 3b. Differences in Demographic and Health Characteristics among Those Not Reporting

Benefit Receipt (check mark shows statistically significant differences between false negatives

and correct negatives

1

)

Age 55 receipt status

Age 63 receipt status

SSDI

SSI

SSDI

SSI

Demographic characteristics

Race

Ethnicity

Gender

Marital status

Socioeconomic characteristics and

employment

Education (years)

Income

Assets

Currently working for pay

Probability living to 75/working to 65

Probability of work-limiting health condition in

next decade

Tenure from longest held job

Total years worked

Health characteristics and behavior

Self-reported health status

Health problems currently limit work

Doctor has ever diagnosed:

Blood pressure

Diabetes

Lung disease

Heart disease

Stroke

Psychiatric problems

Arthritis

Number of diagnosed health conditions

Memory problems

Back problems

Ever smoked/ Smoked now (%)

Number of alcoholic drinks per day

CESD mental health score

2

Number of ADL or IADL difficulties3

Hospital stays in previous two years (%)

Number of doctor visits in previous two years

Out of pocket medical expenditures

N (Correct negatives)

7,795

8,273

5,655

6,370

N (False negatives)

231

128

322

88

32

1

We used a t-test to compare the difference in means and a chi-square test to assess the difference in distributions.

When we tested the distribution, the test statistic is shown for the category heading.

2

Depressive symptoms measured by the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression (CESD), an 8-point battery.

3

Activities of Daily Living (ADLs) and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADLs) are marked 0-5 to

represent the number of ADLs/IADLs in which the respondent reports at least some difficulty.

Notes: All values are taken at the ages 55 or 63, respectively, and all dollar values are inflated-adjusted to 2020

dollars.

Source: Authors’ calculations using the RAND-HRS and SSA data linkage.

Comparing Aggregate Beneficiary Counts in the HRS Self-Reports and Administrative

Linkage to SSA Published Statistics

So far, we have considered the comparison within the HRS respondents of self-reports

and administrative values. We conclude by considering the number of SSDI and SSI

beneficiaries captured in the HRS relative to statistics published by SSA. To align as closely as

possible to published statistics, we made this comparison at two points in time, 2004 and 2010.

Those years reflect the addition of new cohorts to the HRS (Early Baby Boomers and Middle

Baby Boomers, respectively) so that the HRS sample is nationally representative of ages from 51

through FRA, which align with SSA statistics that span 50-FRA for SSDI and 50-64 for SSI. It

is important to note that while the statistics are similar, differences in the age composition of the

comparison as well as being measured at slightly different points in time means that our

comparison is valid within an order of magnitude, but we would not expect complete alignment.

Table 4 shows that: (1) self-reports are lower than administrative values in 2004 and

2010, consistent with our earlier findings, (2) administrative reports are lower than SSA

published statistics in both years, and (3) the magnitude of the discrepancy across sources is

smaller in 2010 than 2004. In 2010, the HRS linked to administrative records identified just

under 4.5 million SSDI beneficiaries, about 75 percent of the 5.8 million in SSA published

statistics. In the same year, the difference between the HRS administrative and published

statistics for SSI was about the same, with the 1.02 million SSI recipients identified based on

HRS administrative records reflecting about 78 percent of the 1.31 recipients in SSA published

statistics.

33

Table 4. Comparison of SSDI and SSI Beneficiaries in the HRS to SSA Published Statistics

SSA published statistic

1

HRS-SSA

administrative

HRS self-reports

SSDI beneficiaries

2004

4,247,536

3,603,152

3,103,867

2010

5,827,321

4,445,529

4,047,090

SSI beneficiaries

2004

1,350,000

994,285

838,508

2010

1,307,000

1,022,837

1,019,542

1

Published values for SSI beneficiaries reported by SSA in thousands.

Notes: SSA values include those ages 50 through FRA (SSDI) and 50 through 64 (SSI), while the HRS values

include those who are 51 through FRA to align with the selection criteria used in this manuscript. HRS values are

weighted to be nationally representative of the non-institutionalized population in the year based on HRS sampling

weights, as described in the text.

Source: SSA published statistics are from Table 4 of the SSDI Annual Statistical report

(https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/statcomps/di_asr/2019/sect01b.pdf) and the 2018 Annual Report of the SSI

program (available at https://www.ssa.gov/oact/ssir/SSI18/IV_B_Recipients.html#1020383). HRS values are

authors’ calculations using the RAND-HRS and SSA data linkage.

There are several possible reasons for the observed differences. First, the HRS sample in

these years is based on sampling weights that make the sample nationally representative of only

the non-institutionalized population. Starting in 2014, the HRS weights better account for

nursing home residence and no longer assign 0 weight to respondents living in an institution, but

that was not true in 2004 or 2010, nor the cohort selection processes for the samples in those

years. We could not find national statistics on the share of under-FRA beneficiaries residing in

institutions, we did find that 4.6 percent of the (unweighted) respondents receiving SSDI in 2010

had a zero survey weight (implying residing in an institution), and 5.2 percent of those receiving

SSI (not shown). Second, until 2016, the HRS only asked questions on SSDI and SSI to those

who reported a health-related work limitation. Those who were not asked the questions are

coded as not receiving benefits, yet we know from other work that about one-fifth of disability

beneficiaries in the CPS did not respond affirmatively to the survey question asking whether they

had a work-limiting health condition (Burkhauser et al. 2014). As a result, we expect that the

HRS self-reports will be lower than the administratively linked values. Those two factors alone

may explain the bulk of the observed gap between HRS reports and SSA published statistics. A

third explanation is that while the HRS is nationally representative on a range of characteristics,

it may not fully capture disability beneficiaries. Given that beneficiaries have significant health

limitations, it may not be surprising that they may be less likely to participate in a long survey

34

like the HRS and that the weighting procedure used by the survey may not account for all their

characteristics. Again though, we caution that we do not know the relative magnitude of these

three factors.

Discussion

We began this project by seeking a definitive answer to whether researchers should use

the HRS self-reported data or the administrative records. Our answer is perhaps an

unsatisfactory “it depends.” In many cases, the self-reported data may be accurate enough—if

receipt of SSI is simply a control variable, the difference between 2 percent and 2.5 percent may

not be important. Yet, if the research question involves the need for benefits status that aligns

with administrative records, or if the project intends to use other information about denied or

allowed applicants such as time to initial decision or reason for denial, the administrative records

are almost certainly better.

Our findings show that among the 15 percent or so of respondents with some information

indicating interactions with federal disability programs, about half of self-reported responses to

questions about having ever applied to or currently receiving SSDI or SSI in the HRS do not

align with the individual’s administrative record maintained by SSA. In general, we found that it

is more likely that respondents fail to report benefits they are receiving than reporting benefits

they are not receiving. On net, we found that the overall prevalence rates of SSDI and SSI

application and receipt when weighted to be nationally representative in the HRS are lower based

on self-reports than based on the administrative data. This is generally true across HRS

respondent ages and across cohorts in the HRS.

Despite level differences in the share of respondents reporting interactions with disability

programs, the patterns of new applications and new receipt across ages and waves in the self-

reported and administrative data look generally similar. In other words, the level differences that

we observe when respondents first enter the survey appear to remain over future waves. This

suggests that the introduction of early OASI benefits at age 62 likely does not exacerbate

misreporting, nor did we find strong evidence that respondents were reporting SSDI when they

meant SSI (the gap when looking at either SSDI or SSI looked about the same as when

considering each program separately).

35

We do not fully understand the causes of misreporting. In some instances, it may be a

mismatch between what is recorded in the administrative data and what is salient to an

individual. An applicant may not know that he or she was considered for SSDI when applying

for SSI or that the lack of a cash payment in the month does not mean beneficiary status has

ended. Yet, as we describe in detail in the appendix primer, most of the reasons we might expect

a mismatch between the data sources would result in an overstatement of self-reports relative to

administrative records. We did find that misreports are non-random and differ across race,

gender, income, employment history, and a number of health conditions and health behaviors.

We also found—as others have with older versions of the files—that consenting to the

administrative linkage is non-random. We attempted to account for this using a simple IPW

scheme that the HRS also uses for its other SSA linkages, though a more in-depth approach to

reweighting, such as exactly matching participants on certain characteristics, may be warranted

in other research contexts. More importantly though, researchers considering using the linked

data should be able to use our analysis to take stock of the effects on sample size. The richness

of the HRS questionnaire should not be understated, but for low-frequency events like disability

benefit receipt, a small sample size made smaller by a less-than-full consenting to the linkage

may make certain research studies intractable. Understanding the sample size loss may lead

some to accept the loss of precision in the self-reports in order to preserve record count.

Another reason that researchers may avoid the administrative records is a very high

barrier to entry. While the HRS has made strides in recent years to streamline and simplify the

process necessary to access the linked data, the documentation to understand and link the files to

the core survey remains complex and limited. Even with the addition of the DAF—which was

designed to support research on disability programs by linking information contained in other

files already accessible by HRS users—a detailed knowledge of SSA programs and program data

is required to work with the linked data. We have attempted to fill some of that gap with this

paper and the associated primer, but caution that the administrative records were not primarily

designed to support research and utmost caution is required to avoid misinterpretation of the

information they contain.