DEVELOPMENT OF PACTRANS

WORKFORCE DEVELOPMENT INSTITUTE

Year 1 – Year 3

FINAL PROJECT REPORT

by

Principal Investigator: Yinhai Wang

University of Washington

Sponsorship

PacTrans and WSDOT

for

Pacific Northwest Transportation Consortium (PacTrans)

USDOT University Transportation Center for Federal Region 10

University of Washington

More Hall 112, Box 352700

Seattle, WA 98195-2700

In cooperation with U.S. Department of Transportation,

Office of the Assistant Secretary for Research and Technology (OST-R)

ii

DISCLAIMER

The contents of this report reflect the views of the authors, who are responsible for the

facts and the accuracy of the information presented herein. This document is disseminated under

the sponsorship of the U.S. Department of Transportation’s University Transportation Centers

Program, in the interest of information exchange. The Pacific Northwest Transportation

Consortium, the U.S. Government and matching sponsor assume no liability for the contents or

use thereof.

iii

TECHNICAL REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE

1. Report No.

2. Government Accession No.

3. Recipient’s Catalog No.

01723928

4. Title and Subtitle

5. Report Date

Development of PacTrans Workforce Development Institute

7/14/2021

6. Performing Organization Code

7. Author(s) and Affiliations

8. Performing Organization Report No.

Yinhai Wang, 0000-0002-4180-5628; Wei Sun (University of Washington), Shane

Brown, 0000-0003-3669-8407, (Oregon State University), Kevin Chang, 0000-0002-

7675-6598, (University of Idaho), Ali Hajbabaie, 0000-0001-6757-1981, (Washington

State University), Billy Connor, 0000-0002-4289-2620 (University of Alaska Fairbank)

2019-ME-UW-4

9. Performing Organization Name and Address

10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS)

PacTrans

Pacific Northwest Transportation Consortium

University Transportation Center for Federal Region 10

University of Washington More Hall 112 Seattle, WA 98195-2700

11. Contract or Grant No.

69A3551747110

12. Sponsoring Organization Name and Address

13. Type of Report and Period Covered

United States Department of Transportation

Research and Innovative Technology Administration

1200 New Jersey Avenue, SE

Washington, DC 20590

Final report, 8/16/2017 – 6/30/2021

14. Sponsoring Agency Code

15. Supplementary Notes

Report uploaded to: www.pactrans.org

16. Abstract

With the emergence of technology and applications in transportation practice, the demand for continuing education and workforce

development is growing. As the Northwest regional transportation research center, PacTrans carries responsibility for transportation

workforce development for Federal Region 10. To fulfill this task and address regional workforce development challenges, PacTrans

saw a clear need to develop an institute to provide professional training and continuing education for Region 10’s transportation

professionals. Bringing together decades of collective experience in educational research and continuing education, the research team

established the PacTrans Workforce Development Institute (WDI) to address increasing workforce development needs. Each university

has its own strengths in transportation research and education and thus makes unique and meaningful contributions to this project. To

better accommodate working professionals’ busy schedules, the PacTrans WDI offers demand-responsive and flexible training services

in both on-site and online settings.

Through survey and outreach activities, the research team identified the gaps between workforce training needs and existing training

opportunities, and it developed training courses to fill these gaps. Specifically, the WDI hasdeveloped and delivered several training

courses, such as Understanding and Applying the Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices, Incorporating Human Factors into

Roadway Design and Crash Diagnostics, Project Management and Key Skill Capability Building. In addition, the WDI hasscheduled the

delivery of several training courses, such as Data Analytics and Tools, Geospatial Analysis for Transportation Planners and

Practitioners, and An Introduction to School Zone Safety.

17. Key Words

18. Distribution Statement

Workforce Development, Professional Training, Transportation Research and Education,

Demand Responsive Training

19. Security Classification (of this report)

20. Security Classification (of this page)

21. No. of Pages

22. Price

Unclassified.

Unclassified.

58

N/A

Form DOT F 1700.7 (8-72) Reproduction of completed page authorized.

iv

SI* (MODERN METRIC) CONVERSION FACTORS

v

TABLE OF CONTENTS

List of Abbreviations ..................................................................................................................... ix

Acknowledgments.......................................................................................................................... xi

Executive Summary ..................................................................................................................... xiii

CHAPTER 1.Introduction............................................................................................................... 1

1.1. Research Background ....................................................................................................... 1

1.2. Problem Statement ........................................................................................................... 3

1.2.1.Workforce Deficiency in Transportation ....................................................................... 4

1.2.2.Insufficient Training Availability for Working Professionals ....................................... 5

1.2.3.Understanding Gaps in Existing Training Supplies and Demands ................................ 5

1.3. Research Objectives ......................................................................................................... 7

CHAPTER 2.Literature and State of Practice Review ................................................................... 9

2.1. Background ...................................................................................................................... 9

2.1.1.Federal Agencies .......................................................................................................... 14

2.1.2.State-Level Agencies ................................................................................................... 17

2.1.3.Associations or Non-Profits ......................................................................................... 19

2.1.4.University-Affiliated Organizations ............................................................................ 23

2.1.5.Other Entities ............................................................................................................... 25

2.2. Current Offerings ........................................................................................................... 27

CHAPTER 3.Region 10 Workforce Development Needs Survey and Analysis .......................... 31

3.1. Background and Research Approach ............................................................................. 31

3.2. Collection, Analysis, and Results ................................................................................... 32

3.2.1.Phase 1 ...................................................................................................................... 32

3.2.2.Phase 2 ...................................................................................................................... 34

3.3. Conclusion ...................................................................................................................... 41

CHAPTER 4.Workforce Development Institute .......................................................................... 44

4.1. Mission 44

4.2. Administrative Structure and Business Model ............................................................... 45

4.3. Online Training Platform ............................................................................................... 46

vi

4.4. E-Learning Capabilities.................................................................................................. 48

CHAPTER 5.Development and Delivery of Training Courses .................................................... 54

5.1. Training Courses ............................................................................................................ 54

5.1.1.Understanding and Applying the Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices

(MUTCD) ...................................................................................................................... 54

5.1.2.Incorporating Human Factors into Roadway Design and Crash Diagnostics .............. 57

5.1.3.Project Management and Key Skill Capability Building ............................................. 58

5.1.4.Transportation Data Analysis and Tools...................................................................... 59

5.1.5.An Introduction to School Zone Safety ....................................................................... 61

5.1.6.Geospatial Analysis for Transportation Planners and Practitioners ............................ 62

5.2. Course Delivery.............................................................................................................. 64

CHAPTER 6.Guidebook for Curriculum Development, Implementation, and Evaluation ......... 68

6.1. Adult Learning ............................................................................................................... 68

6.2. Participant Backgrounds and Expectations .................................................................... 74

6.3. Establishing Course Goals, Outcomes, and Evaluation Measures ................................. 75

6.4. Alignment of Learning Outcomes, Assessments, and Activities to Achieve Overall

Course Goals ......................................................................................................................... 78

6.5. Conclusion ...................................................................................................................... 79

References ..................................................................................................................................... 82

Appendix A ................................................................................................................................. A-1

Appendix B ................................................................................................................................. B-1

Appendix C ................................................................................................................................. C-1

Appendix D ................................................................................................................................. D-1

Appendix E .................................................................................................................................. E-1

Appendix F................................................................................................................................... F-1

Appendix G ................................................................................................................................. G-1

vii

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 1.1 An example TRANSPEED course advertisement in 2004............................................ 2

Figure 1.2 A snapshot of a TRANSPEED training session ............................................................ 2

Figure 1.3 An example TRANSPEED course introduction............................................................ 3

Figure 3.1 Manager (left) and engineer (right) responses to “How important are the

following factors when deciding to attend training?” ................................................. 38

Figure 3.2 Manager (left) and engineer (right) ranking of importance of various possible

training topics.............................................................................................................. 40

Figure 3.3 Technology and soft skills training topics ................................................................... 43

Figure 4.1 PacTrans WDI logo ..................................................................................................... 45

Figure 4.2 PacTrans WDI website ................................................................................................ 47

Figure 4.3 Online course registration ............................................................................................ 48

Figure 4.4 Home page for training course .................................................................................... 50

Figure 4.5 Learning modules ........................................................................................................ 51

Figure 4.6 Couse slide................................................................................................................... 51

Figure 4.7 Course video ................................................................................................................ 52

Figure 4.8 Interface for online training with Zoom ...................................................................... 52

Figure 4.9 Quizzes ........................................................................................................................ 53

Figure 4.10 Survey ........................................................................................................................ 53

Figure 5.1 Training delivery: Understanding and Applying the Manual on Uniform

Traffic Control Devices (MUTCD) ............................................................................ 65

Figure 5.2 Training delivery: Incorporating Human Factors into Roadway Design and

Crash Diagnostics ....................................................................................................... 65

Figure 5.3 Certificate of completion ............................................................................................. 66

viii

LIST OF TABLES

Table 2-1 Advantages and disadvantages of specific methods ..................................................... 12

Table 2-2 Review list of transportation related training opportunities (part I) ............................. 28

Table 2-3 Review list of transportation related training opportunities (part II) ........................... 29

Table 2-4 Review list of transportation related training opportunities (part III) .......................... 30

Table 3-1 Participant locations ..................................................................................................... 35

Table 3-2 Participant experience overview................................................................................... 35

Table 3-3 Overview of discipline areas for managers and engineers ........................................... 36

Table 3-4 Training frequency comparison across managers and engineers ................................. 36

Table 3-5 Frequency and percentage of methods of discovering training opportunities .............. 37

Table 3-6 Examples of topics for which managers and engineers perceive a need for

training but training is not currently available. ........................................................... 40

Table 3-7 Proposed programs of training on transportation topics............................................... 42

Table 6-1 Summary of andragogy design elements and how to address them ............................. 72

Table 6-2 Comparison of pedagogical and andragogical approaches to course design and

implementation ........................................................................................................... 74

Table 6-3 Example questions on course participants’ backgrounds and learning goals............... 75

Table 6-4 Course goals with example outcomes and measures .................................................... 76

ix

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

AASHTO: American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials

ASCE: American Society of Civil Engineers

ATSSA: American Traffic Safety Services Association

CAIT: Center for Advanced Infrastructure and Transportation

CED: Continuing Education and Development, Inc.

CEU: Continuing education unit

CHSC: Center for Health & Safety Culture

CITE: Consortium for Innovative Transportation Education

CTS: Center for Transportation Safety

CVSA: Commercial Vehicle Safety Alliance

FHWA: Federal Highway Administration

FMCSA: Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration

HCM (6th Edition): Highway Capacity Manual

HDM: Highway Design Manual

HSM: Highway Safety Manual

IRF: International Road Federation

ITE: Institute of Transportation Engineers

ITSA: Intelligent Transportation Society of America

ITS PCB: ITS Professional Capacity Building Program

LMS: Learning management system

LTAP Local Technical Assistance Program

MUTCD: Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices

NHI: National Highway Institute

NHTSA: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration

NITC: National Institute for Transportation and Communities

NoCoE: National Operations Center for Excellence

NSC: National Safety Council

NTSB: National Transportation Safety Board

OSU: Oregon State University

PacTrans: Pacific Northwest Transportation Consortium

x

PDH: Professional development hours

RSI: Roadway Safety Institute

TSI: Transportation Safety Institute

T2: Technology transfer

TTA: Transportation Training Academy

TTAP: Tribal Technical Assistance Program

UI: University of Idaho (UI)

UW: University of Washington

WSU: Washington State University

WDI: Workforce Development Institute

WSDOT: Washington State Department of Transportation

WRTWC: West Region Surface Transportation Workforce Center

xi

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank many researchers who have supported this project, especially Dr. Shane Brown

from Oregon State University, Dr. Kevin Chang from the University of Idaho, Mr. Billy Connor

from the University of Alaska-Fairbanks, and Dr. Eric Jessup from Washington State University.

We also thank the Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT) for its support in

identifying training needs and developing training courses.

xii

xiii

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Transportation plays a critical role for our nation’s economy. With increased

transportation activities and reduced highway trust funds, however, our transportation system

faces numerous challenges. Among them, the use of new technologies to enhance the efficiency

and reliability of existing transportation infrastructure is quite remarkable. Their use requires not

simply learning to use a mature technology but also processing large quantities of data and other

information to develop optimal operational strategies, as well as use of supporting tools to

address emerging issues. Obviously, the knowledge learned through college education may not

be sufficient to address the challenges posed by such quickly evolving technologies.

Transportation professionals need access to professional and continuing education courses and

training to help them keep up with new knowledge and technology developments.

As the Northwest regional transportation research center, PacTrans has responsibility for

the task of transportation workforce development for Federal Region 10. To fulfill this task and

address regional workforce development challenges, PacTrans saw a clear need to develop an

institute that would provide professional training and continuing education for Region 10’s

transportation professionals. Bringing together decades of collective experience in educational

research and continuing education, the research team established the PacTrans Workforce

Development Institute (WDI) to address increasing workforce development needs. Each

university has its own strengths in transportation research and education and thus makes unique

and meaningful contributions to this project.

To better accommodate working professionals’ busy schedules, the PacTrans WDI offers

demand-responsive and flexible training services in both on-site and online settings. Through

survey and outreach activities, the research team identified the gaps between workforce training

needs and existing training opportunities and developed training courses to fill those gaps.

xiv

Specifically, the WDI developed and delivered several training courses, such as

Understanding and Applying the Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices, Incorporating

Human Factors into Roadway Design and Crash Diagnostics, Project Management and Key Skill

Capability Building, and more. In addition, the WDI has scheduled the delivery of several

training courses, such as Data Analytics and Tools, Geospatial Analysis for Transportation

Planners and Practitioners, and An Introduction to School Zone Safety.

1

CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION

1.1. Research Background

With support from WSDOT and other transportation agencies, the Civil and

Environmental Engineering (CEE) Department at the University of Washington (UW) operated a

very popular continuing education program called TRANSPEED until 2010. Administered

through the UW’s Professional and Continuing Education (PCE) programs, TRANSPEED

brought transportation engineering professional training and continuing education to

governmental agencies and private firms. It conducted 50 workshops annually that served over

1,400 students. Figure 1.1 shows an example course advertisement in 2004. The offered courses

were all short-term and delivered at different locations—such as Seattle, Bellevue, Vancouver,

and Lacey in Washington—to make it convenient for working professionals to participate.

Figure 1.2 shows a snapshot of a TRANSPEED training session, in which students had hands-on

experience at such training sessions.

Instructors of the TRANSPEED courses were typically working professionals with real-

world experience. Each course was designed to address some specific challenges in engineering

practice. Figure 1.3 shows a brief description of an example training course: the Traffic Signal

Timing and Operations.

2

Figure 1.1 An example TRANSPEED course advertisement in 2004

Figure 1.2 A snapshot of a TRANSPEED training session

3

Figure 1.3 An example TRANSPEED course introduction

1.2. Problem Statement

Transportation plays a critical role in our nation’s economy. With increased

transportation activities and reduced highway trust funds, however, our transportation system

4

faces numerous challenges. Among them, the use of new technologies to enhance the efficiency

and reliability of existing transportation infrastructure is quite remarkable. Their use requires not

simply learning to use a mature technology but also processing large quantities of data and other

information to develop optimal operational strategies, as well as use of supporting tools to

address emerging issues. Obviously, the knowledge learned through college education may not

be sufficient to address the challenges posed by such quickly evolving technologies.

Transportation professionals need access to professional and continuing education courses and

training to help them keep up with the new knowledge and technology developments.

1.2.1. Workforce Deficiency in Transportation

Published by WSDOT, the Gray Notebook

(WSDOT 2018a) highlighted that, agency-

wide, there is a limited annual increase rate of permanent full-time employees (4 percent), and 42

percent of WSDOT employees may retire by the year 2022. Meanwhile, WSDOT also set a goal

of providing leadership training to 500 employees by June 2019 to support the agency’s Talent

Development Strategy (WSDOT 2018b). Training included the utilization of available tools at

WSDOT such as the Learning Management System, Skill Soft, and the Performance

Management System to support staff’s growth and development. Clearly, a critical need to

prepare a qualified workforce in the state DOT was identified. Both newly employed and

existing working professionals need to be trained so that WSDOT can better deal with the

inevitability of future retirements. The “2017 Washington State Employee Engagement Survey,

Employer of choice” (2017) also stressed the value of offering responsive training for “targeted

continuing education and personal growth at work” for recruiting and retaining good employees.

That conclusion was based on poor responses to the questions: “I have opportunities at work to

learn and grow” and “ I am encouraged to come up with better ways to do things.”

5

1.2.2. Insufficient Training Availability for Working Professionals

New employees have high expectations for advancement. Yet existing training

opportunities seem insufficient to help prepare employees for new and changing conditions

related to the demand for transportation and associated technological advances. An online

survey

1

of transportation working professionals from Region 10 revealed that in comparison to

internal training opportunities provided by various organizations, chances for transportation

professionals to get external training are quite limited, for both managers and engineers (Table 3

in appendix). Within WSDOT, the internal training program offers several types of training

opportunities for current employees, but those courses mainly concentrate on soft skill or specific

project training. The WSDOT Learning Management System

2

offers mandatory training,

leadership development training, and consultant services from LEAN. One example of an

external training program is the WSDOT local technical assistance programs (LTAP). These

programs are mainly geared toward the national level or state-based organizations. Programs

such as LTAP tend to be fairly generalized and do not always meet all the needs of all trainees

who work with varied state or regional terms, rules, and even regulations. Therefore, more

localized workforce development training programs are in high demand.

1.2.3. Understanding Gaps in Existing Training Supplies and Demands

A recent deep investigation (by PacTrans 2018)

3

of existing transportation workforce

development training organizations, with broad coverage including federal and state agencies,

associates, and non-profit institutes, as well as university-affiliated training, found that there are

1

Online internet survey conducted by PacTrans to explore the training needs of working professionals in Region 10, for detail

please refer to the summary in the appendix.

2

Learning Management System. (Accessed on Nov.11, 2018 at https://www.wsdot.wa.gov/employment/workforce-development/talent-

development.htm)

3

Literature review conducted by Pactrans to summaries 28 existing training organizations/institutes and organizations with 135

courses on transportation workforce development in the USA. For more details, please refer to the appendix.

6

some big understanding gaps between current training opportunities and demand from potential

trainees. Specifically, even though various on-demand courses are offered (some course

offerings are duplicated), in many training institutes, working professionals’ training needs are

currently not well satisfied. For most participants, location and cost tend to drive training

decisions. If travel is involved or if costs are too high, training opportunities decrease. Therefore,

the easy availability of in-demand training courses significantly influences training opportunities

for working professionals. For that reason, a demand-responsive and flexible training program is

a much more effective platform for delivering advances and context sensitive courses.

Although the TRANSPEED program was popular and far-reaching, it was badly hit by

the most recent financial crisis. After WSDOT and other agencies stopped their funding support,

TRANSPEED closed in 2010. Since then, working professionals have lost easy access to

continuing education, and local need for workforce development has accumulated. With the

recent emergence of technology and applications in transportation practice, such as connected

and autonomous vehicles (CAVs) and smart cities technologies, the demand for continuing

education and workforce development is growing.

As the regional transportation research center, the Pacific Northwest Transportation

Consortium (PacTrans) also has responsibility for transportation workforce development for

Federal Region 10, which comprises Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and Alaska. In 2016, a new

dialog started between transportation agencies and PacTrans to re-establish a new workforce

development program to address the increasing workforce development needs of transportation

agencies and companies in the Pacific Northwest. PacTrans set out to develop a workforce

development institute to support professional training and continuing education for Region 10

transportation professionals.

7

1.3. Research Objectives

The objective of this project was to develop a demand responsive and flexible program,

namely, the PacTrans Workforce Development Institute (WDI), for transportation workforce

development in Washington state. This new program is not a simple re-establishment of the

TRANSPEED program. In addition to the proven advantages of TRANSPEED, it also takes

advantage of new e-learning technology to make training accessible online and available at

trainees’ own paces and schedules. This is not a degree program. Instead, it is a program central

to addressing WSDOT’s workforce development needs by delivering a collection of demand-

responsive, short-term training courses and workshops. Deliverables of this project include the

following:

Design of the PacTrans WDI, including its administrative structure, funding sources,

and business model.

Certificates of continuing education and courses for each certificate program.

Curriculum and candidate instructors for each training course.

A full set of course materials, including lecture notes, assignments, projects, and

exams, for each training course.

An official website for the PacTrans WDI for promotion, course schedules,

registration, and more.

A final research report of this project.

The workforce development program will benefit transportation working professionals in

the following three ways:

It allows busy working professionals to access desired training materials and courses

at their convenient times and locations, and at their own pace.

8

It provides a forum for working professionals and university researchers to jointly

investigate challenges and opportunities associated with new technologies, such as

connected and autonomous vehicles (CAVs), and their potential impacts so that

transportation agencies and companies can be proactive in incorporating the new

technologies into practice.

It directly addresses the continuing education needs of transportation agencies and

companies and thus is critical for enhancing their organizational strength.

9

CHAPTER 2. LITERATURE AND STATE OF PRACTICE REVIEW

2.1. Background

Employee training supports the collective knowledge base of an agency or company and

ensures that staff are educated and equipped with the latest or most pertinent information needed

to complete a project or activity. This training, which falls under the broad umbrella of

workforce development or continuing education, includes topics that range from discipline-

specific in nature to those that focus on organizational dynamics, and they can be presented in a

wide variety of formats, such as in-person presentations, hardcopy materials, and online

offerings.

Individual employees are faced with the responsibilities of completing day-to-day tasks,

managing assignments, and assuring that their knowledge base is current. The challenge of

identifying and understanding new information and requirements can be significant to the

employee. Larger organizations must recognize that the provision of training balances training

needs with each agency’s priorities. When and how frequently should an employee be offered

training opportunities? How does the agency recover its investment? What are the agency’s

philosophies and overall budget allocation with regard to training? What are the philosophies of

individual managers and supervisors? (Chang, 2015)

For civil (and transportation) engineers, there is added recognition that “civil engineers

must learn and apply new technologies that (may not have been) included in a traditional

(academic) curriculum. (Lipinski, 2005) This idea is becoming more true as intelligent

transportation systems and the evolution of autonomous and connected vehicles increasingly

connect the learning pathways of civil engineering, computer science and engineering, and

human psychology. The lack of workforce development to support “improved systems

operational management is becoming a more serious constraint to improving mobility … and the

10

demand of new technologies on staff capabilities has also been recognized in ongoing

professional capacity building efforts at the United States Department of Transportation and in

some university curricula.” (Lockwood and Euler, 2016)

As recently as March 2017, the American Society of Civil Engineers’ Board of Direction

(ASCE) adopted a new policy statement suggesting that student learning at the college level

should be expanded. “ASCE supports the attainment of the Civil Engineering Body of

Knowledge for entry into the practice of civil engineering at the professional level (i.e.,

practicing professional engineer) through appropriate engineering education and experience, and

validation by passing the licensure examinations. To that end, ASCE supports an increase in the

amount of engineering education, such that the requirements for licensure would comprise a

combination of:

“A baccalaureate degree in civil engineering;

“A Master's degree in engineering, or no less than 30 graduate or upper level

undergraduate technical and/or professional practice credits or the equivalent

agency/organization/professional society courses which have been reviewed and

approved as providing equal academic quality and rigor with at least 50 percent being

engineering in nature; and

“Appropriate experience based upon broad technical and professional practice

guidelines which provide sufficient flexibility for a wide range of roles in engineering

practice.

“ASCE encourages institutions of higher education, governments, employers, engineers, and

other appropriate organizations to endorse, support, promote, and implement the attainment of an

11

appropriate engineering body of knowledge for individual engineers.” (ASCE, Denver, CO

October 12-15, 2018)

The Transportation Education Council of the Institute of Transportation Engineers one

year earlier undertook a complementary effort to identify employers’ opinions of the

expectations and desires for a transportation engineering degree program. This effort involved

conducting an initial assessment to identify key characteristics that employers are looking for in

new graduates entering the transportation engineering field, with “willingness to learn” identified

as the highest-ranked item. People skills, writing skills, and general analytical skills were also

listed as important characteristics. When queried on exposure to technical subject matter taught

at universities, practitioners highlighted two topics: familiarity with the MUTCD (Manual on

Uniform Traffic Control Devices) and intersection capacity and level of service analysis. Other

topics rated as medium to high importance included but were not limited to the following:

familiarity with the Highway Capacity Manual (HCM), pedestrians and bicycles (complete

streets), traffic signal phasing and timing, and horizontal and vertical roadway design. (Hawkins

and Chang, 2016)

These examples highlight the importance of making certain that young professionals are

exposed, in terms of both breadth and depth, to essential technical competencies and, when

appropriate, additional learning in the form of workforce development training or continuing

education. It is also important to note that workforce development consists of not only increased

knowledge but also mentorship and other professional-related opportunities. (Martin and Glenn,

2002)

In terms of training delivery methods, a broad range of offerings is available, and with

the advent of technology, opportunities to “bring” the training to the employee is becoming

12

much more prevalent. Table 2-1 presents a list of common methods. Each method offers its own

advantages and disadvantages, and each is generally influenced by costs associated with travel or

staff time, the timeliness of the information provided, the expertise provided by the individual or

individuals leading the training, and the resulting learning format, which may or may not be

conducive to a particular individual. (Chang, 2015)

Table 2-1 Advantages and disadvantages of specific training delivery methods

Method

Advantages

Disadvantages

Presentations (live and

virtual)

Opportunity for interaction and

discussion; affords participants the

flexibility to ask questions and

clarify understanding

Presenters must be able to

effectively communicate and

provide useful information;

requires travel by participants

(live presentations)

(Hands-on) Training

Opportunity for interaction; allows

participants to ask questions;

opportunity for attendees to learn;

environment creates knowledgeable

staff and workforce

Schedule conflicts; can be

difficult to establish balanced

training across all staff

members; details much match

need; can be expensive

Webinars

Reduces or eliminates travel time;

can reach a larger audience; recorded

or archived presentations can be

reviewed; duration can be flexible

Lack of interaction between

presenter and audience;

typically requires an internet

connection and software

application; difficult to

implement hands-on activities

Videos

Can be viewed at the discretion of

the user; content to be accessed by a

large audience (i.e., YouTube); more

lively than written documents

May not necessarily be relatable

to user; content and perspectives

can become outdated over time;

production costs could be

significant

Handbooks

Comprehensive; can be used as a

reference guide; contains useful

information provided in a detailed

manner

Printing costs (for hardcopies);

may not be used regularly;

exhaustive to read; bulk can be

intimidating

Decision-Support Tools

Provides information that is

conducive to making an informed

decision; allows users to apply

knowledge developed from past

experiences at a broad level

May require extensive use of

technology and learning;

reliance on good data can be

restrictive; larger systems can be

cost-prohibitive

Community of Practice

Support

Participants share common interest;

team-oriented environment; multiple

opportunities for networking and

interaction

Participants may lack the

necessary skills and

background; organizations must

develop a clear understanding of

how knowledge will be applied

in practice

13

Note that among the methods listed in table 2-1, online programs require program

development and long-term commitment that are often expensive and cost-prohibitive despite the

programs’ increasing popularity. (Mason, 2003) For example, the Global Road Safety course at

the University of Iowa had found success as an in-person, academic credit-based course.

However, when consideration was given to developing an online interactive version open to

parties outside of the university, costs (associated with registration ) and scheduling challenges

grounded the effort. For these reasons, a short-course format was ultimately “found to be much

more successful in attracting participants.” (Hamann and Peek-Asa, 2017) A separate study

noted that “some of the most important considerations of successful online training programs

(for staff at a state department of transportation) are (a) the inclusion of interactive components

within the training modules to keep participants engaged, (b) a short duration for each of the

training modules to retain participants’ attentiveness, and (c) the provision of quizzes to assess

participants’ understanding of the material.” (Islam, 2017)

This study further acknowledged that an effective online training program can “develop

the skillset of personnel both efficiently and effectively, and help facilitate capacity building of

transportation professionals.” A majority of the DOTs that were interviewed acknowledged that

online training was required of their employees, suggesting that DOTs were “making online

training programs as a part of their capability building efforts.” (Islam, 2017)

To address workforce development needs, particularly in regard to transportation-related

topics, the Federal Highway Administration, in partnership with the U.S. Departments of Labor

and Education, has established five regional transportation workforce centers to enhance

transportation workforce development more strategically and efficiently. Establishment of these

centers arguably represents one of the first concerted efforts to consolidate and prioritize the

14

need for such training opportunities. These centers are designed to “create, coordinate, and

facilitate partnerships with state departments of transportation and education, industry, and other

public and private stakeholders to enhance transportation workforce development throughout the

education continuum,” and these centers also “facilitate middle school and high school activities,

training in technical schools and community colleges, universities, and post-graduate programs,

and professional development services for incumbent transportation workers.” (Martin, 2015)

The Pacific Northwest is served by the West Region Surface Transportation Workforce Center

(WRTWC) at the Western Transportation Institute at Montana State University in partnership

with the Upper Great Plains Transportation Institute.

The WRTWC is not alone in offering training. In fact, within the transportation (safety)

domain, there are a plethora of entities that currently offer training in a wide range of topics.

Below are listed federal agencies, state-level agencies, associations and non-profits, university-

affiliated centers and programs, and other entities. Although this summary is not an exhaustive

list, the breadth of offerings available is evident and suggests that workforce development and

continuing education opportunities are indeed plentiful to the interested consumer.

2.1.1. Federal Agencies

National Operations Center for Excellence

Website: transportationops.org

The National Operations Center for Excellence (NOCoE) is a partnership of the

American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO), the Institute

of Transportation Engineers (ITE), and the Intelligent Transportation Society of America

(ITSA), with support from the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA). The NOCoE features

an Operations Technical Services Program, funded through contributions from state

15

transportation agencies and FHWA, to provide peer exchange webinars, training, capacity

building programs, and practice area forums.

National Center for Rural Road Safety

Website: ruralsafetycenter.org

The National Center for Rural Road Safety, or Safety Center, was “created to identify the

most effective current and emerging road safety improvements and deploy them on rural roads.”

The Safety Center currently hosts a free webinar each month; topics include Creating a Rural

Transportation Planning Organization and Sharing the Road with Slow Moving Vehicles. A

lengthy list of archived webinars is available for viewing, and the center sends out a weekly

email about traffic safety events available through other organizations.

National Transportation Safety Board Training Center

Website: www.ntsb.gov/Training_Center/Pages/TrainingCenter.aspx

The National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) Training Center “provides training for

NTSB investigators and others from the transportation community to improve their practice of

accident investigation techniques.” Attendance is primarily limited to parties related to NTSB

investigations, safety and law enforcement members, and members of the academic community

working on relevant research projects. Courses range in length from one day to as long as two

weeks.

Transportation Safety Institute (U.S. Department of Transportation)

Website: www.transportation.gov/transportation-safety-institute

The Transportation Safety Institute (TSI), which is part of the U.S. Department of

Transportation, provides training to “safety professionals in federal, state and local government

agencies and private industry.” Offerings include face-to-face courses, live online courses, and

general online courses. TSI courses cover all major modes of transportation, including general

automobile, bus, rail, and aviation for both passenger and freight hauling. Note that the National

16

Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) training center is folded under the TSI’s

Highway Safety Division. Training is offered in several different forms and includes online

classes on topics such as Milestones of Highway Safety, History of Impaired Driving, and

History of Speed Program Management. NHTSA also has a dedicated website that provides short

articles on various safety topics such as teen driving, pedestrian and bicycle safety, and

motorcycle safety.

National Highway Institute

Website: www.nhi.fhwa.dot.gov/about-nhi

The National Highway Institute (NHI), which represents the training and education

branch of the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA), was established in 1970 and seeks to

improve the “conditions and safety of our nation's roads, highways, and bridges [by]

continuously building on the skills of highway professionals and enhancing job performance in

the transportation industry across the country.” The program offers courses in eighteen

transportation industry program areas; course examples include Roadside Safety Design

(instructor-led training) and the safe and effective use of law enforcement personnel in work

zones (web-based training).

Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration

Website: www.fmcsa.dot.gov/

The Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration (FMCSA) was established within the

U.S. Department of Transportation in 2000. The mission of the FMCSA is to prevent

commercial motor vehicle-related fatalities and injuries; activities include increasing safety

awareness. The FMCSA works with federal, state, and local enforcement agencies, the motor

carrier industry, and labor and safety interest groups. The majority of courses are not oriented to

driver training but are designed to serve law enforcement officers.

17

Intelligent Transportation Systems (USDOT)

Website: www.pcb.its.dot.gov/default.aspx

The Intelligent Transportation Systems Joint Program Office offers the ITS Professional

Capacity Building Program (ITS PCB) to provide the ITS workforce with “flexible, accessible

ITS learning through training, technical assistance and educational resources. The program

assists transportation professionals by developing their knowledge, skills, and abilities to build

technical proficiency while furthering their career paths.” The ITS PCB hosts training courses

and features an archive of nearly 200 online webinars on topics such as automated and connected

vehicles and other transportation technology.

2.1.2. State-Level Agencies

T2 Center

Website: www.techtransfer.ce.ufl.edu/t2ctt/default.asp

The Florida Transportation Technology Transfer (T2) Center is part of the University of

Florida Transportation Institute (UFTI). The T2 Center provides training, technical assistance,

technology transfer services, and safety information to transportation, public works and safety

professionals, and the general public. Its mission is to “transform engineering research and

technology into common practice and to foster a safe, efficient, environmentally sound

transportation system by improving skills and knowledge.” Program offerings include its Local

Technical Assistance Program (LTAP), Pedestrian & Bicycling Safety Resource Center (SRC),

Florida Occupant Protection Resource Center (OPRC), and Technology Transfer Support.

18

Minnesota DOT

Website: www.dot.state.mn.us/trafficeng/education/index.html

As a state-level example, the Office of Traffic, Safety and Technology in the State of

Minnesota “establishes guidelines and procedures [by building] relationships between state,

county and city engineering staff to resolve questions about engineering and roadway safety.”

The Minnesota Department of Transportation provides technical leadership and works closely

with professionals to identify professional continuing education needs. An online database is

dedicated to traffic engineering, with webinars (mostly free) and learning modules that are

divided into specialty areas ranging from basic road work safety to traffic management plans.

Minnesota LTAP

Website: www.mnltap.umn.edu/training/online/

The mission of the Minnesota Local Technical Assistance Program (LTAP), in

partnership with the University of Minnesota, is to “improve the skills and knowledge of local

transportation agencies through training, technical assistance, and technology transfer.” The

LTAP provides both online training and workshop opportunities. Course topics range from

work-zone traffic control, to sign maintenance and management, to gravel road maintenance and

design.

Technology Transfer Program

Website: www.techtransfer.berkeley.edu

The Technology Transfer Program is the California transportation community's source

for professional training, expert assistance, and information resources and is a division of the

Institute of Transportation Studies at the University of California, Berkeley. The program

“provides training, workshops, conferences, and technical assistance in the transportation-related

areas of planning and policy, traffic engineering, project development, infrastructure design and

19

maintenance, safety, environmental issues, complete streets, multimodal transportation, railroad

and aviation.”

Transportation Training Academy

Website: uva-tta.net

The University of Virginia’s Transportation Training Academy (TTA) provides local

transportation professionals across Virginia with knowledge to design safe and efficient

transportation systems. The TTA offers “informative, innovative, and affordable training and

professional development programs tailored to meet the workforce development needs of

Virginia’s state and local government agencies in order to improve the level of transportation

services provided to the traveling public.” The vast majority of TTA’s events are on-site training,

but it also provides limited availability of online materials, webinars, and training videos.

2.1.3. Associations or Non-Profits

American Society of Civil Engineers

Website: www.asce.org/education_and_careers/

The American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) is a “leading provider of technical and

professional conferences and continuing education, the world’s largest publisher of civil

engineering content, and an authoritative source for codes and standards that protect the public.”

Training opportunities are provided in four different forms: webinars, seminars, guided online

courses, and on-site training. Most courses broadly focus on civil engineering-related topics as

opposed to exclusively focusing on transportation or traffic. Specific examples include 90-

minute webinars, one- to three-day long seminars, and guided online courses six to twelve weeks

long featuring video lectures, interactive exercises, case studies, live webinars, and weekly

discussion topics.

20

Institute of Transportation Engineers

Website: www.pathlms.com/ite/

The Institute of Transportation Engineers (ITE) is “an international membership

association of transportation professionals who work to improve mobility and safety for all

transportation system users and help build smart and livable communities. Through its products

and services, ITE promotes professional development and career advancement for its members,

supports and encourages education, identifies necessary research, develops technical resources

including standards and recommended practices, develops public awareness programs, and

serves as a conduit for the exchange of professional information.” Many of its webinars are

tailored to transportation engineers or an engineering audience.

American Traffic Safety Services Association

Website: www.atssa.com/TuesdayTopics

The core purpose of the American Traffic Safety Services Association (ATSSA) is to

advance roadway safety. Its members “accomplish the advancement of roadway safety through

the design, manufacture, and installation of road safety and traffic control devices,” and the

association “brings together members, road safety experts, and public agencies to identify and

solve road safety issues. [Its] primary focus is to move Toward Zero Deaths on our nation’s

roads.” ATSSA offers many transportation-related courses, ranging from certification to training

to webinars, and online training ranges from flagger training to an introduction to the MUTCD.

One particular training opportunity, Tuesday Topics, offers 30- minute webinars that are focused

on the roadway safety industry, traffic control, and innovative technologies, among other

subjects.

21

ITS America

Website: www.itsa.org

The members of ITS America are “leading the technological modernization of our

transportation system by supporting the research, deployment, and public policy for the future of

intelligent transportation systems. Collaboration [exists] between private companies, public

agencies, research institutions and academia while educating the public about the importance of

intelligent transportation systems.” The mission of ITS America is to “create a policy

environment that drives ITS and Internet of Things development and deepens industry

engagement.” ITS America’s annual showcase event is its annual meeting, which features

presentations on vehicle connectivity, electrified vehicles, and other topics. Through its

Knowledge Center, webinars, reports, and a technology scan and assessments are available.

National Safety Council

Website: www.nsc.org/learn/Safety-Training/Pages/defensive-driving-driver-safety-

training.aspx

The National Safety Council (NSC) is a nonprofit, safety advocacy organization with the

mission of “eliminating preventable deaths at work, in homes and communities, and on the road

through leadership, research, education and advocacy.” The NSC focuses on preventing injuries

and deaths at work, in homes and communities, and on the road. With regard to roadways, NSC

focuses on distracted driving, teen driving, and driver training. The NSC pioneered defensive

driver education and trains many drivers each year to become safer drivers. The Council leads

Road to Zero, the national initiative aimed at eliminating traffic fatalities within 30 years.

Commercial Vehicle Safety Alliance

Website: cvsa.org/eventpage/events/cvsa-workshop/

The Commercial Vehicle Safety Alliance (CVSA) is a nonprofit association that

comprises local, state, provincial, territorial, and federal commercial motor vehicle safety

officials and industry representatives. The Alliance seeks to “achieve uniformity, compatibility

22

and reciprocity of commercial motor vehicle inspections and enforcement by certified inspectors

dedicated to driver and vehicle safety.” CVSA oversees several programs aimed at educating

inspectors and improving the safety of commercial vehicles in areas such as air brake

effectiveness and unsafe driving behaviors.

International Road Federation Global

Website: www.irf.global

The International Road Federation (IRF) is an international non-profit group based in

Washington D.C. The IRF assists countries in “progressing toward better, safer and smarter road

systems” by developing and delivering knowledge resources, advocacy services, and continuing

education programs. Its Global Training Curriculum provides technical expertise in classroom

and practical settings where attendees learn from and have direct access to seasoned

professionals.

Tribal Safety

Website: tribalsafety.org

The tribalsafety.org website represents an online clearinghouse for practitioners. It was

developed by the Alaska Tribal Technical Assistance Program (TTAP) in partnership with

participating tribes, federal and state partners, and TTAP Centers. Although the Tribal

Transportation Safety Management System Steering Committee uses the site to share

information with members, a variety of resources, ranging in topics from safety planning and

data to impaired driving and roadway departure, are provided to the public. Links to archived

webinars and regional safety summits are also shared.

Safety Fest Boise

Website: safetyfest-boise.org

Safety Fest is an example of an annual regional event that provides free safety and health

training to workers, supervisors, and managers. The event enables many of the Pacific

23

Northwest’s “frontline workers” to learn methods to reduce hazards that can cause workplace

fatalities, injuries, and illnesses. Attendee topics range from construction to general industry to

mine safety and health.

2.1.4. University-Affiliated Organizations

University of Maryland

Website: www.citeconsortium.org

The Consortium for Innovative Transportation Education (CITE) was established in 1998

to provide “transportation engineering students and professionals with an integrated curriculum

covering the technologies and management subjects associated with Intelligent Transportation

Systems (ITS).” The curriculum broadly focuses on information technology, transportation

engineering, project management, performance management, systems engineering, and ITS

technology. CITE offers training in three different formats: blended (instructor-led), self-paced

(independent study), and full semester.

Portland State University

Website: nitc.trec.pdx.edu

The National Institute for Transportation and Communities (NITC) is currently one of

five U.S. Department of Transportation national university transportation centers (UTC). As a

national UTC, the NITC hosts frequent online webinars that are archived on the website and

available for any user to view for free. These webinars cover a variety of transportation topics,

including shared streets and bicycle/pedestrian accessibility and safety; its existing archive

features over 500 such resources.

University of Minnesota

Website: www.roadwaysafety.umn.edu

The Roadway Safety Institute (RSI) is a regional university transportation center that

“conducts activities to advance domestic technology and expertise in the many disciplines that

24

make up transportation through education, research, and technology transfer activities at

university-based centers of excellence.” RSI activities focus on user-centered transportation

safety systems with an overarching goal of preventing crashes to reduce fatalities and life-

changing injuries. Its research incorporates both engineering and social sciences, and a majority

of RSI’s seminars incorporate some type of safety topic.

Rutgers University

Website: cait.rutgers.edu

The Center for Advanced Infrastructure and Transportation (CAIT) is another national

university transportation center and hosts periodic courses on transportation topics such as

asphalt design, traffic regulations, and bridge maintenance. CAIT activities seek to advance the

“safe, efficient, economical, and environmentally sound movement of people and goods in our

nation and beyond,” with the majority of its work focusing on the USDOT strategic areas of state

of good repair, economic competitiveness, and safety.

Montana State University

Website: chsculture.org

The Center for Health & Safety Culture (CHSC), which is part of the Western

Transportation Institute at Montana State University, is an “interdisciplinary center serving

communities and organizations through research, training, and support services to cultivate

healthy and safe cultures. The Center is dedicated to applying research to develop sustainable

solutions to complex social problems, and its research focuses on understanding how culture

impacts behavior—especially behavior associated with health and safety.” Current research

projects include addressing substance abuse, traffic safety, child maltreatment, and violence.

CHSC holds an annual symposium on how a positive culture can help promote a healthy society.

25

2.1.5. Other Entities

Lifesavers Conference

Website: lifesaversconference.org

The annual Lifesavers Conference represents “the largest gathering of highway safety

professionals in the United States” and “brings together a unique combination of public health

and safety professionals, researchers, advocates, practitioners and students committed to sharing

best practices, research, and policy initiatives that are proven to work.” The Conference covers a

variety of transportation safety topics, including distracted motorists and pedestrians, drugged

driving, driving under the influence, and autonomous vehicles.

360training.com

Website: www.360training.com/environmental-health-safety/transportation-safety-

training

360training.com offers and has developed a safety training course for drivers of large

trucks and buses and a similar course for drivers of cars, vans, and small trucks.

360training.com’s courses are aimed at companies that would buy the training in a package for

multiple employees. In addition to driver safety training, 360training.com offers a DOT

supervisor training course on how to determine whether employees are sufficiently exhibiting

safe behavior while operating vehicles.

National Safety Compliance

Website: www.osha-safety-training.net

National Safety Compliance offers a variety of safety-related training. Although its

primary focus area relates to Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA)

compliance, some of its training resources and materials (i.e., accident investigation, driving

safety, powered industrial trucks) tangentially relate to transportation safety.

26

OHSA.com Transportation Safety Courses

Website: www.osha.com/courses/transportation.html

OHSA.com offers online OSHA training (and on-demand training) that is tailored for

drivers or employees. Its transportation safety training programs are created for safety managers,

safety trainers, construction employees, employees who deal with safety hazards or

environmental hazards, and general workforce employees. They are designed “for drivers to

improve their driving skills and learn the rules and laws when on the road.” These courses target

commercial vehicle drivers to “enhance their skills and make them sharper and more aware when

on the road.”

IMPROV

Website: www.myimprov.com

Interactive Education Concepts (IEC), under the trade name Traffic School by Improv,

Improv Traffic School, and Driver License Direct by Improv, has been providing behavior-based

driver education, traffic school, and defensive driving programs to students for 20 years. Improv

has “won numerous awards from the media and other organizations over the years for its unique

curriculum that is written by professional Hollywood writers and based on humor.” As an

example, Improv offers an Idaho-approved, 30-minute-long defensive driving course for $28.

CED Engineering

Website: www.cedengineering.com

Continuing Education and Development, Inc. (CED) provides “online engineering

continuing education courses, video presentations and live webinars to licensed professional

engineers to enhance their engineering knowledge and competence as well as to assist them in

fulfilling their Continuing Professional Competency (CPC) requirements by earning their

professional development hours (PDH) and continuing education unit (CEU) credits mandated

by their respective state licensing boards.” CED offers a large selection of transportation

27

engineering courses featuring topics such as bicycle planning and safety and identifying

optimum intersection lane configuration and signal phasing.

Center for Transportation Safety

Website: centerfortransportationsafety.com

The Center for Transportation Safety (CTS) is part of Driving Dynamics, Inc. Driving

Dynamics is a “leading provider of advanced performance driver safety training and fleet risk

management services throughout North America.” CTS offers behind-the-wheel driver

education, simulator-based training, online learning, and driver risk management to help fleet-

based organizations reduce potential crash rates.

2.2. Current Offerings

To capture the breadth of transportation and traffic safety-related offerings actively

available to practitioners and members of the general public, a snapshot of current offerings was

compiled during the last two weeks of January 2018. Course offerings were compiled by topic,

host organization, format, length, and cost, based on available information. An abbreviated

summary, alphabetized by offering title, is shown in tables 2-2, 2-3, and 2-4.

28

Table 2-2 Review list of transportation-related training opportunities (part I)

29

Table 2-3 Review list of transportation-related training opportunities (part II)

30

Table 2-4 Review list of transportation-related training opportunities (part III)

31

CHAPTER 3. REGION 10 WORKFORCE DEVELOPMENT NEEDS SURVEY AND

ANALYSIS

The goal of this task was to gain a better understanding of the existing training or

professional development needs within Region 10 (i.e., Idaho, Alaska, Oregon, and Washington).

To complete the task, Pactrans and researchers from Oregon State University and the University

of Idaho collaborated to design and implement a workforce development study. This study

contained two major components: interviews with local transportation offices and the

development and distribution of an online survey. Below are a description of the empirical

approaches used to conduct interviews and develop the survey; the findings from our data

collection efforts; and a discussion of major themes that emerged from a descriptive analysis of

workforce development needs.

3.1. Background and Research Approach

The research presented herein can be best described as a sequential, exploratory, mixed-

methods project (Creswell, 2013). More specifically, the research design took place across two

distinct phases. During the first phase, qualitative data (e.g., interviews) were collected and

analyzed. These findings were then used to inform the development and execution of the second,

quantitative phase (e.g., survey development). This research approach is particularly useful in

cases where relatively little is known about the topic of interest, and in which initial open-ended

perspectives can provide direct insight into subsequent research. Given the goal of exploring

perspectives regarding services that do not yet exist, a sequential, exploratory, mixed-methods

design suited the project well.

32

3.2. Collection, Analysis, and Results

3.2.1. Phase 1

3.2.1.1 Structured Telephone Interviews

During the first phase of the research, we conducted structured, qualitative interviews

with transportation engineering managers, practitioners, and learning coordinators across Region

10. Participants were recruited through personal contacts among the research teams at Oregon

State University (OSU), the University of Idaho (UI), Washington State University (WSU), and

the University of Washington (UW), as well as Internet directory searches through each state’s

transportation website (e.g., Oregon Department of Transportation). Researchers also

implemented snowball sampling, in which current participants helped to identify additional

candidates to interview. In total, 17 participants were interviewed, including three from

Washington, one from Idaho, eleven from Oregon, and two from Alaska. Interview questions

asked participants to talk about three major topics: 1) their access to or awareness of training

opportunities; 2) the factors that affect whether to attend training; and 3) any perceived urgent or

compelling needs within transportation engineering training. Interviews lasted approximately 15

minutes each and were conducted over the phone. They were not audio recorded, but a

researcher took field notes as they were conducted for later analysis.

3.2.1.2 Awareness and Access

Participants were asked to describe a typical training experience, including the means

through which they heard about the training. In general, participants tended to find out about

most training opportunities through some form of email listserv. As individuals began to attend

training and/or join various professional societies, the opportunities to find out about training

33

opportunities increased. Some participants also noted conducting Google searches or reaching

out to training coordinators, but such actions were often in response to a specific training need.

3.2.1.3 Factors Affecting Training Decisions

A wide range of factors was noted as influential to the choice to attend training (or in the

case of managers, to send an employee to training). For most participants, location and cost

tended to drive training decisions. If travel was involved or if costs were too high, training

opportunities might be more challenging. Another salient factor was the relevance of the training

to current workplace needs. If a training program of upcoming webinar was related to a project

in the near future, the training was seen as more valuable.

In addition to the timeliness of the training, participants noted the importance of being

able to gain practical skills that they could apply in their jobs. Hands-on training was seen as

especially valuable, in contrast to programs that educated on theories or rules or information that

was seen as less directly applicable to current work. Put simply, congruence between training

and upcoming work was a key driver in decision making related to attendance.

Beyond the content of the particular training program, participants noted the importance

of the presenter or organization conducting the training. Participants noted that some people or

organizations had stronger reputations than others, and so when making choices about training, it

was helpful to inquire about the skills or reputation of the presenter.

3.2.1.4 Current Training Topic Needs

The final portion of the structured interview asked participants to think of topic areas or

content for which training would be helpful but training does not currently exist. Most

participants reiterated the importance of alignment of training topic area with current workplace

demands, but some larger categories emerged from the discussion. In particular, there seem to be

34

persistent training needs related to safety, operations, and maintenance. As laws, rules, and

regulations shift, it is important that engineers and managers are up-to-date on the changes. As

technology becomes more ubiquitous in traffic engineering, including the use of software, big

data, and other applications, ensuring employee competence with these new advances is

essential.

3.2.2. Phase 2

3.2.2.1 Survey Development and Distribution

Following the interviews, the researchers used the descriptive analysis to inform the

development of items and response choices. By leveraging our first qualitative phase to inform

the second phase, our results were empirically grounded in responses from practitioners. The

survey was again distributed on the basis of the personal contacts of the researchers in the four

collaborative universities noted above, as well as the managers who had participated in the

qualitative interviews. The full results, separated by managers and engineers, is provided in the

appendix. The following sections provide some highlights across the two groups. Important to

note about the following results is that not all respondents completed the survey entirely or

responded to all the questions. There were also questions for which respondents could select

several choices. In some cases, total responses to particular items may have slightly different

overall totals.

3.2.2.2 Demographics

As of April 30, 2018, 184 individuals had responded to the survey, including 63

managers and 121 practitioners. Table 3-1 provides a breakdown of the states from which

respondents came.

35

Table 3-1 Participant locations

Alaska

Oregon

Washington

Idaho

Other

Managers

42

7

12

0

2 (CA)

Engineers

45

46

23

3

2 (CA, Norway)

Table 3-2 provides an overview of the amount of experience reported by both managers

and practitioners. All managers reported more than five years of experience in transportation

engineering, broadly, while there was a wider range of experience with their current positions.

Engineers tended to have less experience, both in transportation in general as well as their

current jobs in particular.

Table 3-2 Participant experience overview

Experience in Transportation (yrs)

Experience in current job (yrs)

<1

1-2

3-5

5+

<1

1-2

3-5

5+

Managers

0

0

2

63

7

11

12

3

Engineers

5

9

12

93

27

22

20

51

In terms of disciplines represented within transportation engineering, results suggested a

relatively diverse group of concentrations in specific fields. Table 3-3 provides an overview of

the fields reported by managers and engineers. In this case, respondents could select several

responses at the same time, depending on the nature of their work. Notable here is the high

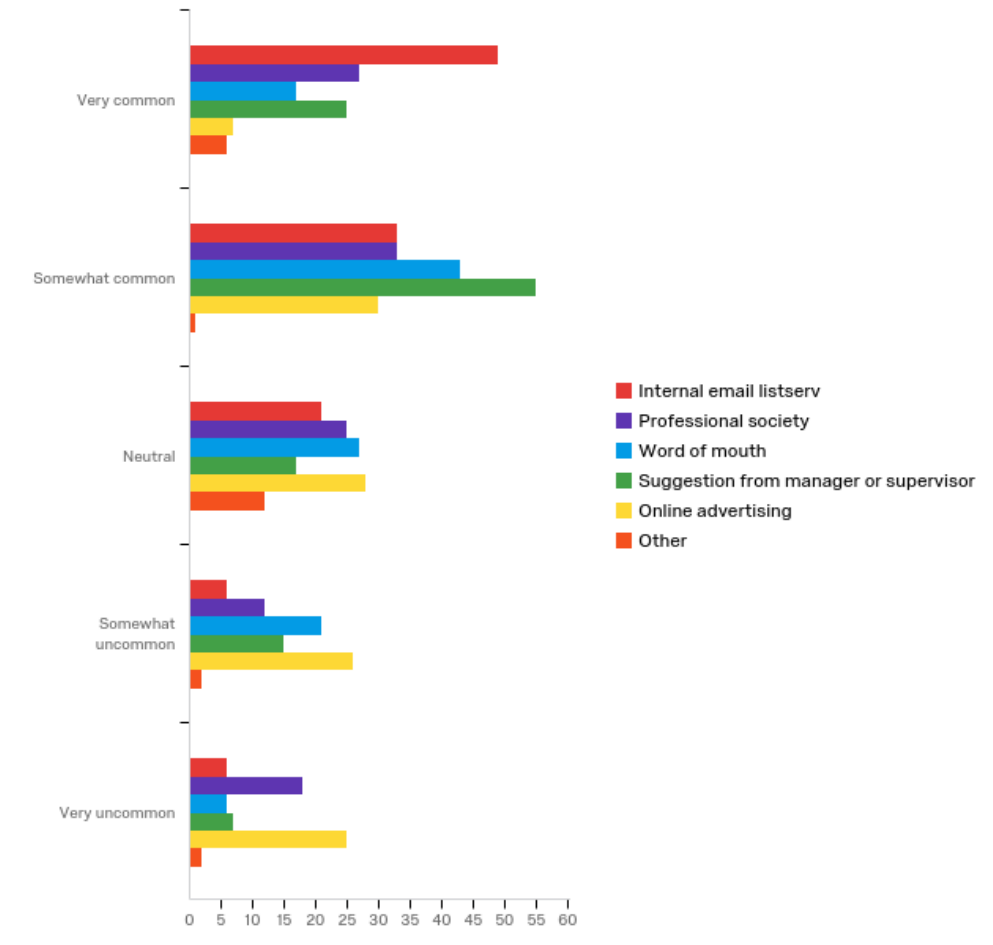

proportion of “Design” as a discipline, suggesting that such activities might be common across