Page 1 of 4

Statutory Sickness Support

A new sick pay system that supports

employees and employers

May 2022

THE REPORT

Page 2 of 45

ABOUT THIS REPORT

This WPI Economics report, commissioned by Unum, contributes to the growing literature that highlights

About Unum

Unum is a leading employee benets provider oering

nancial protection through the workplace including

Group Income Protection, Life Insurance, Critical Illness,

and Corporate Dental cover.

We are committed to workplace wellbeing for both

employees and employers. We have a wide range of

tools designed to help businesses of all sizes create

or enhance their employee wellbeing strategies,

including our award-winning Help@hand app which

oers employees fast, direct access to quality health

and wellbeing support services, including remote GPs,

mental health support and physiotherapy.

Our Income Protection customers also have access to

medical and vocational rehabilitation expertise designed

to help people stay in work and return to work following

illness and injury. Our Employee Assistance Programme

provided by LifeWorks, includes help and advice on a

range of work/life issues.

Our Critical Illness customers can access our Cancer Support

Service, provided by Reframe, providing personalised

support for employees with a cancer diagnosis.

Unum is a values-driven, purpose-led organisation, with

an operating model centred on doing good for society

and being there for people when they need us most.

Being a socially responsible business is at the heart of

our ‘We are Unum’ values and where we aim to excel.

We’re focussed on providing positive and eective

contributions to the communities in which we live

and work, and see helping our communities as a

natural extension of the commitment we make to

our customers every day.

Our mission is to be the most inclusive, diverse and

welcoming company in our market – creating a place

where people aspire to work, and where everyone is

able to contribute their best and succeed, whatever

their identity or background.

We are signatories of the HM Treasury Women in

Finance Charter, Business in the Community Race at

Work Charter and the Armed Forces Covenant, where

we hold the Silver Employer Recognition Scheme Award.

We are also a Disability Condent Leader, Stonewall

Diversity Champion, and have been awarded the Gold

Payroll Giving Quality Mark for our charitable initiatives.

At the end of 2021, Unum protected 1.6 million people

in the UK and paid claims of £366 million - representing

£7 million a week in benets to our customers -

providing security and peace of mind to individuals

and their families.

Page 3 of 45

ABOUT THIS REPORT

Our parent company, Unum Group provides a broad

portfolio of nancial protection benets and services in

the workplace through its Unum US, Unum UK, Unum

Poland, and Colonial Life businesses. In 2021, Unum

Group reported revenues of US$12 billion and paid

US$8.2 billion in benets.

For more information, please visit www.unum.co.uk.

Unum Limited is authorised by the Prudential Regulation

Authority and regulated by the Financial Conduct

Authority and the Prudential Regulation Authority.

Unum Dental is a trading name of Unum Limited.

Registered in England 983768.

About WPI Economics

WPI Economics is a consultancy that provides economics

that people understand, policy consulting and data

insight. We work with a range of organisations —

FTSE100 companies, SMEs, charities, and central

and local government — to help them inuence and

deliver better outcomes through improved public

policy design and delivery. Our focus is on important

social and economic policy debates, such as net zero,

levelling up and poverty, productivity, and mental

health. We are driven by a desire to make a dierence,

both through the work we undertake and by taking

our responsibilities as a business seriously. We are an

accredited Living Wage employer.

About the authors

Matthew Oakley

Director, WPI Economics

Matthew founded WPI Economics in 2015. He

is a respected economist and policy analyst, having spent

well over a decade working in and around policy making in

Westminster. He has previously been Chief Economist at

Which?, and Head of Economics and Social Policy at Policy

Exchange. He began his career as an Economic Advisor at

the Treasury. He holds an MSc in Economics from UCL.

Joe Ahern

Head of Policy Consulting, WPI Economics

Joe is an experienced policy professional, and

leads WPI’s policy work across a range of areas including

nancial services and climate adaptation. Before joining

WPI Economics, he spent ve years working in a range of

roles at the Association of British Insurers. Prior to the

ABI, Joe worked in the communications team at the New

Schools Network and before that, in the oce of Andrew

Jones MP. He holds a degree in in Politics and Sociology

from the University of Sheeld.

Simon Hodgson

Head of Public Policy, Unum

Simon leads Unum’s public policy

engagement and works to raise awareness of the

role of employee benets. He joined Unum from the

Government’s joint Work and Health Unit where he led

development of its strategy on workplace health.

Page 4 of 45

CONTENTS

5

6

9

10

15

OUR FIVE SUCCESS CRITERIA 22

25

39

44

Page 5 of 46

are the engine our country relies on to propel

Right now, we’re failing to take good care of our people,

and it’s holding our country back. Far too many people

are falling out of work for health reasons, impacting

not just our nation’s economy, but individuals and their

families too.

The UK has a problem with sickness absence. Over

140 million working days were lost to it in 2018.

1

Ill

health stopping us working is estimated to cost our

economy up to £130 billion a year

2

— that’s three

times the defence budget.

3

Sickness absence is an

enormous drag on our economy — tackling it should

be a top priority.

That doesn’t mean eliminating it altogether — all of

us will need to have time o work now and again to

look after our health. What it does mean is ensuring

that we’re taking great care of our people while they’re

o sick, and, most importantly, maximising their

chances of getting back to the job they love.

At the root of the problem is Statutory Sick Pay. It’s a

system that turns 40 years old this year,

4

and it’s really

showing its age. As the world of work has changed, sick

pay has failed to keep up. The current system oers

no protection at all for the lowest-paid, and misses

the opportunity to promote early intervention and

empower employers to deliver the right support.

Sick pay in the UK has hit its mid-life crisis — it’s time for

a change.

This report sets out our approach to that challenge: to

move from a system focused purely on payments, to

one that’s designed to deliver proactive and eective

support. So that’s what we called it: Statutory Sickness

Support.

A simple package of reforms can transform our

country’s whole approach to work and health. Sick pay

that’s t for the 2030s, not the 1980s, that takes account

of exible working, lets you come back to work part

time, and gives every employee better protection than

today. And an exciting package of support so that small

businesses across the UK can level up the health and

wellbeing of their workforce.

Overhauling sick pay will protect our people, boost our

businesses, and energise our economy. This report sets

out how.

Mark Till

CEO, Unum International

1

ONS, Sickness absence in the UK labour market (2019)

2

Department for Work and Pensions & Department of

Health, Work, Health and Disability Green Paper Data Pack

(2016), p. 15

3

House of Commons, UK Defence Expenditure (Commons

Briefing Paper 8175) (2022), p.5

4

Social Security and Housing Benefits Act, 1982

Page 6 of 46

Ill health stopping people from working is

estimated to cost our economy up to £130

5

On top of these costs, ill

health-related worklessness is estimated to cost

6

Reducing

At the heart of how we manage sickness absence in the

UK is Statutory Sick Pay (SSP), the minimum statutory

payment made by employers to employees who are

absent for health reasons. SSP was introduced in the

early 1980s

7

to replace state sickness benet and is

currently paid at a pro-rated rate of £99.35 per week

8

for up to 28 weeks to employees who meet the

eligibility criteria.

Because employers are no longer required to record

and report payments of SSP,

9

it is dicult to know how

much is paid out and to whom. While an estimated

141.4 million working days were lost to sickness

10

in

2018, the number of absences resulting in payment is

far smaller as a result of SSP’s various eligibility criteria,

including ‘waiting days’ and the exclusion of around

2 million workers

11

with earnings too low to qualify.

Around 18 million ‘SSP-eligible days’ are taken by 6

million employees a year, with direct costs to employers

(i.e. employees are o sick and receiving sick pay at the

level of SSP) of between £100 million to £250 million.

12

There are variations in the types of employees who get

SSP or who get additional sick pay from their employer.

Since SSP’s introduction, the proportion of employers

choosing to go beyond it and provide enhanced

‘occupational sick pay’ (OSP) above the minimum has

fallen, from 56% in 1988

13

to 28% in 2019.

14

Up to

around 70% of employees eligible for SSP are presently

paid more through formal or informal arrangements.

15

It is thought that employees in large organisations

(more than 250 employees) are 1.5 times more likely to

be paid OSP than those in small organisations.

16

For the vast majority of people, the at rate SSP

payment of £99.35 per week is very low compared to

their normal earnings. This ‘replacement rate’ — the

proportion of previous pay covered — is much lower

in the UK than in comparable advanced European

economies.

17

What’s more, as the world of work has

evolved, SSP hasn’t kept up. Over the last 40 years, the

way we all live and work has changed dramatically, with

many more of us working exibly, part-time or in the

gig economy. SSP has also not evolved to take account

of our ageing population, or to learn from the policy

successes in other advanced economies. The result is a

sick pay system that is no longer t for purpose.

5

Department for Work and Pensions & Department of

Health, Work, Health and Disability Green Paper Data Pack

(2016), p. 15

6

Work, Health and Disability Green Paper Data Pack (2016),

p. 16

7

Social Security and Housing Benefits Act, 1982

8

GOV.UK, Statutory Sick Pay (SSP): What you’ll get (2022)

9

HM Government, The Statutory Sick Pay (Maintenance of

Records) (Revocation) Regulations 2014 (2014)

10

ONS, Sickness absence in the UK labour market (2019)

11

TUC, TUC accuses government of abandoning low-paid

workers after it ditches sick pay reforms (2021)

12

WPI Economics, 2022, Statutory Sick Pay: modelling

costs and reforms. Available: http://wpieconomics.com/

publications/modelling-ssp/

13

House of Commons, House of Commons Debate (2

November 1988, vol. 139, col. 645-6W)

14

HM Government, Health is everyone’s business: proposals to

reduce ill health-related job loss (2019), p. 35

15

WPI Economics, 2022, Statutory Sick Pay: modelling

costs and reforms

16

Department for Work and Pensions and Department of

Health and Social Care, Health in the workplace – patterns

of sickness absence, employer support, and employment

retention (2019), p. 26

17

TUC, Welfare States: How generous are British benefits

compared with other rich nations? (2016), p. 28

Page 7 of 46

The outdated SSP system and its focus on providing

very low levels of payment and not on promoting

eective and proactive sickness absence management

results in other undesirable policy outcomes. These

include higher state expenditure on social security

benets — in eect, subsidising low levels of employer

funded sick pay — and the Exchequer costs of the

current system at around £850 million a year, meaning

that the direct costs of the current system are likely to

be greater for the government than for business.

18

The government believes that too low a rate of sick

pay undermines the economic incentive for employers

to invest in reducing absence.

19

The current system

does not encourage or guide employers to provide

comprehensive and eective sickness absence

management support. Reform of SSP has the potential

to strengthen employer incentives to reduce levels of

sickness absence. Insurance models oer a way to pool

risks and resources with other rms, and allow even the

smallest employers to access a comprehensive package

of support which has a strong track record of improving

absence outcomes.

It is clear that the current system is not working for our

economy, for our health, or for our society. We believe

that to be successful, a new system must provide:

· A targeted safety net that protects workers and

encourages returns to work where possible

· Eective employer incentives to act and invest in

better workplace health

· Support for the competitiveness of our economy,

reducing costs and supporting innovation

· Increased tax revenue and reduced spending on

social security benets

· Broad cross-party support and appeal to a range of

stakeholders across society.

To deliver on these objectives, we propose moving from

the current system, which is primarily concerned with

prescribing payments, to an enhanced system that goes

beyond simply resolving the nancial element of SSP

and instead encourages proactive and eective support.

We call our proposed system Statutory Sickness Support.

Statutory Sickness Support would x our country’s

broken sick pay system, by:

· Widening eligibility, so all workers are protected

· Bringing the rules up to date, to allow ‘phased returns’

and accommodate exible working

· Simplifying calculation and administration for

employers

· Strengthening the safety net to reduce ‘income

shocks’ and alleviate poverty.

18

WPI Economics, 2022, Statutory Sick Pay: modelling

costs and reforms

19

HM Government, Health is everyone’s business: proposals to

reduce ill health-related job loss (2019), pp. 34-35

Page 8 of 46

Reforming sick pay in line with our proposals would

generate savings for the Exchequer of around £120

million a year as well as projected wider economic

benets of around £500 million.

20

Our proposals would

go further however, and Statutory Sickness Support

would deliver a shot in the arm for the system by

unlocking £500 million to level up SME investment in

workplace health across the UK, with:

· Stronger guidance and support for employers to

manage absence

· A new conditional rebate of SSP costs to directly

reward employers’ eorts

· A workplace health stimulus package to enable SME

investment in proven support.

Our system would provide better protection for Britain’s

workers, and especially the low-paid, with the majority

of the benet of our reforms accruing to workers

earning less than £25,000 a year. Many more workers

would have access to health and wellbeing support

at work, reducing the risk and length of absence and

supporting a strong economy, benets system and

health service.

Based on conservative assumptions, economic

benets could be in excess of £1 billion in year one,

accompanied by £400 million in Exchequer benet

(reduced spending and increased tax receipts). By year

ve, economic benets could be up to £3.9 billion, and

over £1 billion in Exchequer savings.

21

20

WPI Economics, 2022, Statutory Sick Pay: modelling

costs and reforms

21

WPI Economics, 2022, Statutory Sick Pay: modelling

costs and reforms

Sickness absence and health-related job loss

Combatting this policy challenge is crucial to

Ill health stopping people from working is estimated

to cost our economy up to £130 billion each year

22

— roughly equivalent to total planned pre-pandemic

health spending in England

23

or more than three times

the defence budget.

24

On top of these costs, ill health-

related worklessness is estimated to cost government

up to £29 billion in foregone tax and National Insurance

contributions.

25

Tackling the policy challenge of sickness

absence is a clear policy imperative — with the potential

to unlock billions in tax receipts and increased

economic output.

For families, we know that being out of work for health

reasons is also a major driver of poverty; half (50%)

of people in poverty live in a family where someone

is disabled.

27

More broadly, we know that work can

be good for health

28

and worklessness is strongly

correlated with serious negative health outcomes.

29

For

employers, there are very large benets to reducing

sickness absence. As well as the clear implications

in terms of lost output, there are broader knock-on

eects of potentially positive impacts on mental health,

reduced presenteeism and increased productivity.

30

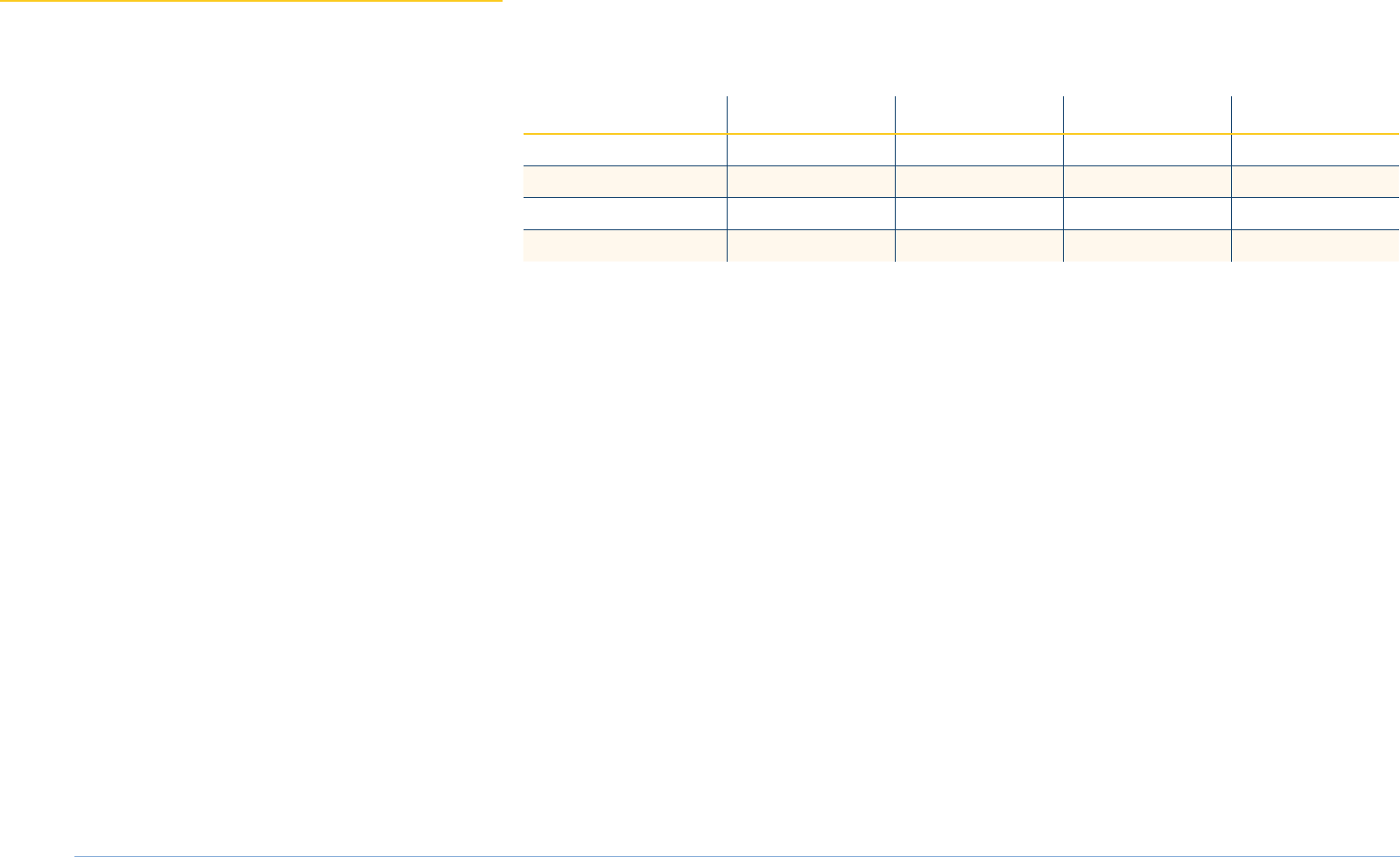

Estimated annual economic costs of ill health preventing work among working age people, 2016

26

Cost element Description Estimated cost

Costs to UK

economy

Sickness absence Lost output due to sickness absence £15-20bn

Economic inactivity Lost output due to working age ill health that prevents work £73-103bn

NHS costs Extra treatment costs for conditions aecting ability to work £7bn

Informal care giving Lost output due to working age carers caring for working age sick < £1bn

Total cost

£95-130bn

Costs to

government

Benet payments Employment and Support Allowance and associated benets £19bn

NHS costs (as above) Extra treatment costs for conditions aecting ability to work £7bn

Exchequer owbacks Tax receipts foregone due to health-related worklessness £21-29bn

Total cost

£47-55bn

22

Department for Work and Pensions & Department of

Health, Work, Health and Disability Green Paper Data Pack

(2016), p. 15

23

The King’s Fund, The Health Foundation, and Nuffield

Trust, Budget 2018: What it means for health and social care

(2018), p. 3

24

House of Commons, UK Defence Expenditure (Commons

Briefing Paper 8175) (2022), p.5

25

Work, Health and Disability Green Paper Data Pack (2016), p. 16

26

Department for Work and Pensions & Department of

Health, Work, Health and Disability Green Paper Data Pack

(2016), pp. 15-16

27

Social Metrics Commission, Measuring Poverty (2020), p. 11

28

Department for Work and Pensions & Department of

Health, Improving Lives: the Work, Health and Disability Green

Paper (2016), p. 10

29

Benach, J., Carles, M. and Santana, V., Employment

Conditions and Health Inequalities: Final Report to the WHO

Commission on the Social Determinants of Health (2007),

pp. 105-106

30

Deloitte, Mental health and employers (2022), p.8, 23

Page 10 of 46

31

It is paid

32

to those

that an employee earning at least £123 a week,

For those without access to an occupational sick pay

(OSP) scheme (enhanced sick pay in excess of that

prescribed by SSP paid voluntarily by employers), these

eligibility criteria reduce the likelihood of payment in the

event of sickness. The at rate of SSP means that those

who receive it get a very low rate of pay compared to

what they would typically take home.

The requirement for businesses to record and report

payment of SSP was removed in 2014,

33

which makes the

exact scale of SSP in payment and the associated costs

for businesses hard to quantify. What we can estimate

condently is that eligibility for SSP is likely to be relatively

limited as compared to the total number of sick days

taken. In 2018, an estimated 141.4 million working days

were lost to sickness.

34

However, the vast majority of

those sick days (around 70%) are not eligible for SSP,

primarily because of the ‘waiting days’ eligibility criterion.

35

Eligibility is further reduced by the fact that some of

those o sick for 4 days or more will not be classed

as employees, are earning less than the earnings

threshold, or are ineligible because of one of the other

criteria for claiming SSP. Bringing all of these together,

there are around 18 million ‘SSP-eligible days’ taken by

around six million people each year.

37

31

Social Security and Housing Benefits Act, 1982

32

GOV.UK, Statutory Sick Pay (SSP): What you’ll get (2022)

33

HM Government, The Statutory Sick Pay (Maintenance of

Records) (Revocation) Regulations 2014 (2014)

34

ONS, Sickness absence in the UK labour market (2019)

35

WPI Economics, 2022, Statutory Sick Pay: modelling costs

and reforms

36

Ibid

37

WPI Economics, 2022, Statutory Sick Pay: modelling costs

and reforms

58

12

9

17

1

3

1-2 days 3 days 4 days 5 days 6 days 7+ days

% of those with some sickness absence

Ineligible

for SSP

Distribution of sickness absence by spell length, 2017

36

Source: WPI analysis of Office for National Statistics, Social Survey Division. (2018). Annual Population Survey, 2004-2017: Secure Access. [data collection]. 13th Edition.

UK Data Service. SN: 6721, http://doi.org/10.5255/UKDA-SN-6721-12

Page 11 of 46

As highlighted above, eligibility for SSP requires an

individual to be earning at least £123 a week — the so-

called ‘Lower Earnings Limit (LEL). Beyond the point at

which a worker becomes eligible for SSP (£123 a week, or

a salary of slightly over £6,000 a year), the at rate makes

SSP unrelated to their previous level of pay. This means

the amount the vast majority of people receive in SSP

is very low compared to their normal earnings. We can

think of this as the ‘replacement rate’ — the proportion of

previous pay covered.

The at rate of SSP creates clearly undesirable eects in

practice:

2 million employees with earnings below the LEL —

70% of them women

38

— are not eligible for SSP at all

The replacement rate of SSP has a very sharp peak at

around the eligibility threshold

After this point, the replacement rate falls very quickly,

meaning that for employees earning more than

£18,000 a year, the weekly replacement rate is less

than 30%.

Replacement rate of SSP (%) by gross annual salary

Annual salary

Source: WPI Economics modelling

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

£48,100

£45,500

£42,900

£40,300

£37,700

£35,100

£32,500

£29,900

£27,300

£24,700

£22,100

£19,500

£16,900

£14,300

£11,700

£9,100

£6,500

£3,900

£1,300

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

Current SSP replacement rate (%)

£48,100£45,500£42,900£40,300£37,700£35,100£32,500£29,900£27,300£24,700£22,100£19,500£16,900£14,300£11,700£9,100£6,500£3,900£1,300

38

TUC, TUC accuses government of abandoning low-paid

workers after it ditches sick pay reforms (2021)

Page 12 of 46

To put it another way, on an annualised basis, an employee working full time and

earning around the National Living Wage would go from a salary of about £18,500 to sick

pay of around £5,500.

The wide variance in replacement rates makes it important to understand the incomes

of those who are o work sick and likely to be eligible for and in receipt of SSP. Little

robust evidence currently exists on this. Our estimates using Annual Population Survey

data are shown below, and overlay the proportion of the SSP population at each point

of the income distribution, with the replacement rates shown above. Around 75% of the

SSP-eligible population earn less than £25,000 a year.

39

WPI Economics, 2022, Statutory Sick Pay: modelling costs

and reforms

Replacement rate of SSP (%) and distribution of SSP-eligible population by income

39

Annual salary

£48,100

£45,500

£42,900

£40,300

£37,700

£35,100

£32,500

£29,900

£27,300

£24,700

£22,100

£19,500

£16,900

£14,300

£11,700

£9,100

£6,500

£3,900

£1,300

0%

12%

24%

36%

48%

60%

72%

84%

0

12

24

36

48

60

72

84

Current SSP replacement rate (%)

4810045500429004030037700351003250029900273002470022100195001690014300117009100650039001300

0%

3%

6%

9%

12%

15%

18%

21%

0

3

6

9

12

15

18

21

total SSP elig pop % of total

494004810046800455004420042900416004030039000377003640035100338003250031200299002860027300260002470023400221002080019500182001690015600143001300011700104009100780065005200390026001300

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

total SSP elig pop % of total

Current SSP replacement rate (%)

494004810046800455004420042900416004030039000377003640035100338003250031200299002860027300260002470023400221002080019500182001690015600143001300011700104009100780065005200390026001300

Current SSP replacement rate (%) Total SSP eligible population (% of total)

Total SSP eligible population (% of total)

Current SSP replacement rate (%)

Page 13 of 46

To understand the costs of the SSP system to business,

we need to assess the extent to which these costs

actually ‘bite’ for employers. For those employers who

already voluntarily pay enhanced sick pay well above

the minimum requirements, the level of SSP is unlikely

to impact their behaviour or costs. The rate of SSP only

represents an actual or ‘biting’ cost for those employers

who only pay the minimum mandated amount of

sick pay.

One analogy might be the National Minimum Wage

or National Living Wage. While this is a legally

enforced statutory minimum rate of pay for all

employees, increases have no relevance to the costs

of employment in respect of employees who already

earn signicantly more.

Since SSP’s introduction, the proportion of employers

choosing to go beyond it and provide OSP has fallen,

from 56% in 1988

40

to 28% in 2019.

41

Despite this, the number of employees employed in

businesses relying on the statutory minimum is smaller

than this would suggest. For example, survey evidence

suggests that six in ten workers (57%) receive their

usual full pay when they are o sick, whether through

the operation of formal OSP schemes, or more informal

arrangements where pay simply continues in the case

of absence.

40

House of Commons, House of Commons Debate

(2 November 1988, vol. 139, col. 645-6W)

41

HM Government, Health is everyone’s business: proposals to

reduce ill health-related job loss (2019), p. 35

Page 14 of 46

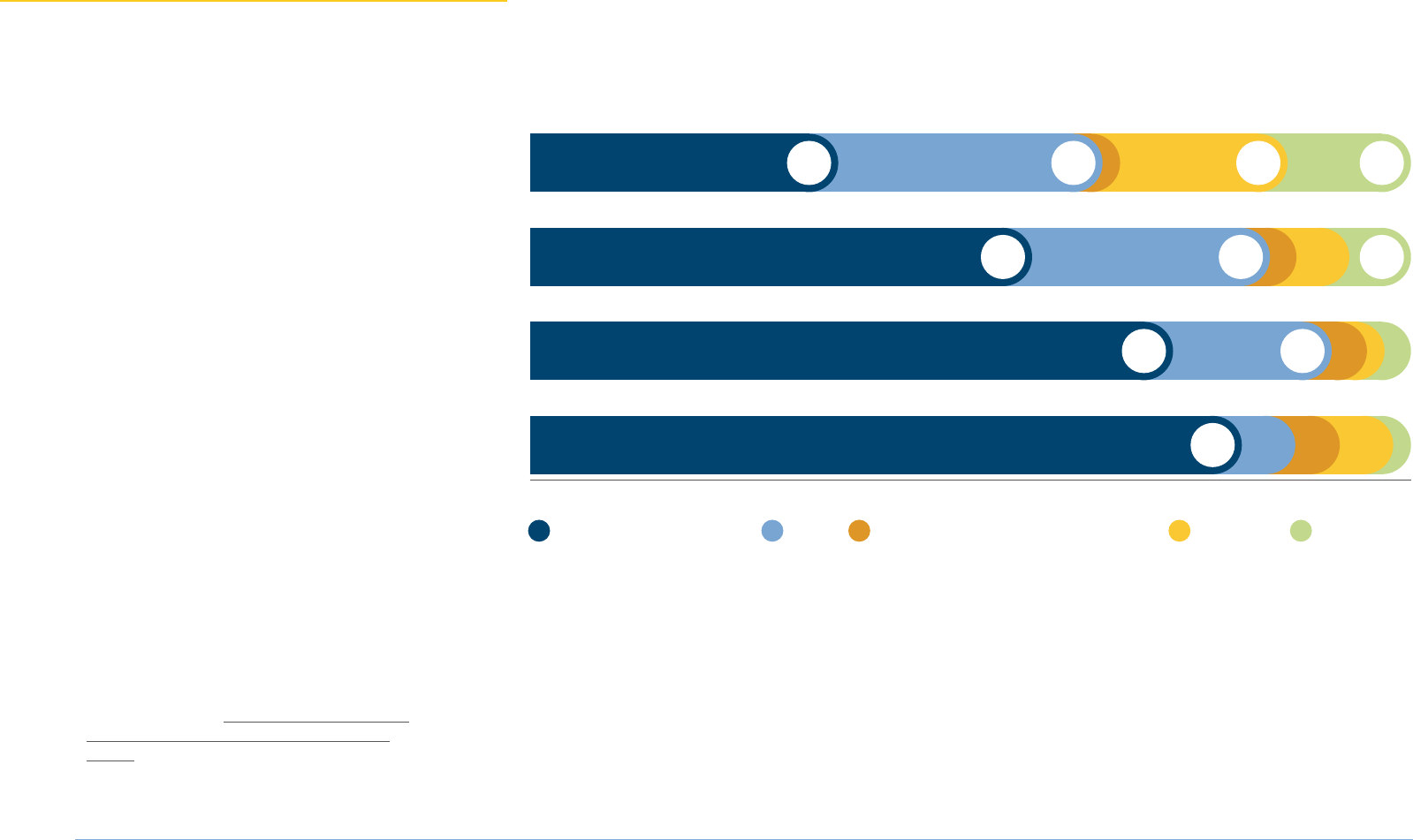

Based on this evidence, up to around 70% of employees

eligible for SSP are presently paid more through

formal or informal arrangements.

43

It is thought that

employees in large organisations (more than 250

employees) are 1.5 times more likely to be paid above

the level of SSP than those in small organisations.

44

The total direct employer costs in respect of employees

for whom the costs of SSP are ‘binding’ (i.e. employees

who are o sick and receiving sick pay at the level of

SSP) fall somewhere in the range of £100 million to £250

million a year.

45

42

TUC, based on polling by Britain Thinks

43

WPI Economics, 2022, Statutory Sick Pay: modelling costs

and reforms

44

Department for Work and Pensions and Department of

Health and Social Care, Health in the workplace – patterns

of sickness absence, employer support, and employment

retention (2019), p. 26

45

WPI Economics, 2022, Statutory Sick Pay: modelling costs

and reforms

Employee-reported sick pay arrangements by income bracket, 2021

42

Your full pay as usual SSP More than SSP, less than full pay Nothing Don't know

Source: TUC, Sick Pay that Works

0% 20% 40% 60% 80% 100%

Up to £15k

£15-£29k

£29-£50k

£50k+

35% 30% 14%

7%

18%

57%

73%

80%

19%

27%

Page 15 of 46

The introduction of Statutory Sick Pay in the early

46

time making all employers directly responsible

Statutory Sick Pay remains one of the main ways

by which the relationship between an employer

and a sick or disabled employee is currently

But, as the world of work has evolved, Statutory Sick

Pay has failed to keep up. Over the last 40 years, the

way we all live and work has changed dramatically, with

many more of us working exibly, part-time or in the

gig economy. SSP has also not evolved to take or ageing

population into account, or to learn from the policy

successes in other advanced economies. The result is a

sick pay system that is no longer t for purpose.

This chapter provides an overview of some of the

adverse impacts of the current system.

Higher levels of insecurity and poverty

The pandemic has brought into sharp focus

the extent to which those in receipt of SSP

suer from a lack of a safety net. The equivalent gross

hourly rate for those on SSP is only £2.76.

47

This is much

lower than similar advanced economies.

In many other developed countries, the sick pay

system prevents a sharp fall in income that risks

making a worker’s nancial circumstances precarious.

48

A Trades Union Congress analysis highlighted the

low replacement rate in the UK compared to similar

European nations.

46

Social Security and Housing Benefits Act 1982

47

This represents the weekly SSP payment of £99.35 spread

over a 36-hour week

48

Institute for Public Policy Research, Working Well: A Plan to

Reduce Long-Term Sickness Absence (2017), p. 42

Page 16 of 46

Where replacement rate varies over period of sickness or between groups of employees, the

highest rate is reported. Durations expressed as the nearest number of complete months to the

statutory maximum. Where a range exists, the upper bound is reported.

UK: at-rate benet (replacement rate based on average earnings). France: employer makes up

dierence between benet and salary, so replacement rate is 100% in practice.

Comparison of sickness benefit and sick pay protection in selected developed countries, 2012

49

Minimum gross replacement of benefit on average earnings

Maximum duration of sickness benefit (months)

0%

25%

50%

75%

100%

0

6

12

18

24

Austria

Belgium

Finland

France

Germany

Ireland

Luxembourg

Netherlands

Norway

Sweden

UK

49

Adapted from TUC, Welfare States: How generous are British

benefits compared with other rich nations? (2016), p. 28

Page 17 of 46

The existing evidence base paints a worrying picture of

the human impact of low sick pay.

· Two-thirds of respondents surveyed by Mind said that

receiving SSP had caused them nancial problems. For

some it had caused them to go into debt. A quarter

of respondents specically mentioned that SSP had

impacted on their ability to buy food or pay their bills.

50

· A Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development

(CIPD) survey found that just under a quarter (23%)

of workers who would receive either SSP or no pay in

event of sickness absence due to coronavirus would

struggle to pay bills or buy food within just a single

week. This gure rose to a third (33%) of respondents in

the event of needing to take 2 weeks o work.

51

Research suggests that the impacts of SSP go beyond

the nancial and can even catalyse a vicious cycle.

Three-fths of respondents to Mind’s survey stated that

the reduction in income as a result of SSP negatively

impacted on their mental health, with a quarter adding

that this impact had slowed down their recovery.

“ I was signed o due to depression and

anxiety. I was meant to take 2 weeks to

recover but I couldn’t as I was constantly

aware that I would not be getting paid

much and I’ll struggle nancially. It really

aected me.”

52

The low rate of SSP impeding recovery is not a

phenomenon limited to those with mental health

conditions. Cancer patients have also faced worrying

challenges as a result of a lack of protection. Cancer

support specialists Reframe provide case studies as part of

research conducted for this report, such as the one below.

53

Following her cancer diagnosis, Hannah was

unable to work as her treatment regime

rendered her bedbound. She was only entitled to

SSP from her employer, and this had a signicant

impact on her nances.

A prolonged period away from work caused money

to become so tight that Hannah consulted with her

treating care team to reduce her treatment dosage

so she could return to work part-time.

Hannah returned to work part-time. Because

SSP does not accommodate so-called ‘phased

returns’, she was not entitled to any sick pay for

the hours she was not able to work. Despite her

returning to work part-time, Hannah was still

struggling to make ends meet.

With the help of support from Reframe, Hannah

was able to make a claim for state benets and was

referred to local food banks. Hannah also needed

to contact her energy supplier and tell them about

her cancer diagnosis to make sure they wouldn’t

cut o the supply to her home.

50

Mind, Statutory Sick Pay: Our Research (2019)

51

CIPD, Some workers face financial hardship in just one week if

they have to take time off for Coronavirus (2020)

52

Mind, Statutory Sick Pay: Our Research (2019)

53

Case study provided by Reframe Cancer Support. The

patient’s name has been changed to protect their privacy.

Page 18 of 46

This analysis suggests that, at present, SSP fails to provide a basic safety net for some

of the most vulnerable workers in the UK. This is a signicant problem on its own and

should be particularly concerning in the context of rising costs for essential expenditure

such as food and energy.

Higher welfare spending

Some of those receiving SSP will be eligible for social security benets,

although not all will realise this or make a claim. Where employees are claiming

social security benets (now likely to be Universal Credit), low replacement rates are

counteracted somewhat by the tax and benets system. As their weekly income falls, the

tax they owe decreases and their benet award may increase. This osets somewhat the

income shock of moving onto SSP and means that net incomes are not as heavily impacted

as gross incomes. The below chart shows the theoretical impact of tax and benets.

Notional replacement rate of SSP, and effective replacement rate after tax and benefits (%)

54

Annual salary

Source: WPI Economics modelling

£48,100

£45,500

£42,900

£40,300

£37,700

£35,100

£32,500

£29,900

£27,300

£24,700

£22,100

£19,500

£16,900

£14,300

£11,700

£9,100

£6,500

£3,900

£1,300

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

SSP replacement rate (%) with UC

Current SSP replacement rate (%)

£49,400£48,100£46,800£45,500£44,200£42,900£41,600£40,300£39,000£37,700£36,400£35,100£33,800£32,500£31,200£29,900£28,600£27,300£26,000£24,700£23,400£22,100£20,800£19,500£18,200£16,900£15,600£14,300£13,000£11,700£10,400£9,100£7,800£6,500£5,200£3,900£2,600£1,300

Current SSP replacement rate (%) SSP replacement rate (%) with UC

54

WPI Economics, 2022, Statutory Sick Pay: modelling costs

and reforms

Many employees on SSP, in practice, will not be claiming benets. This means they will

not see a rise that compensates their move onto SSP. Very few of those earning more

than £25,000 a year are in families that claim means-tested benets, and so the vast

majority of people earning above £25,000 per year amount face an eective replacement

rate lower than 20%.

While it is positive that the benets system provides an additional emergency safety net

for the individual, it comes with a signicant burden for the Exchequer. This is a little-

raised point in recent discussion of SSP: Its low rate shifts the burden of supporting sick

employees towards the state, signicantly increasing welfare spending.

Overall, the Exchequer costs of the current system are estimated to be around £850

million a year,

55

including people who are not paid SSP because they are o sick for

fewer than 4 days but nonetheless see a reduction in earnings and therefore an increase

in benets such as Universal Credit. In short, the direct costs of the current system are

likely greater for the government than for business.

On top of this, the current system does not eectively incentivise or support employers

to invest in preventing and managing sickness absence, which is likely to increase

disability benet onow.

Disability benet spending was projected to be a record £58 billion in 2021/22, of which

£33 billion of support was for working-age people.

56

Limited employer incentives

Employers play a central role in managing and reducing levels of sickness absence.

A review of international systems of sick pay conducted by the OECD in 2010 concluded

that employers should “be given a much more prominent role in sickness monitoring

and sickness management [as] they are in a good position to judge what work their

employees can still do and what work or workplace adjustments might be needed to

[address] the health problem that has arisen.”

57

55

Ibid

56

Department for Work and Pensions, Shaping Future

Support: The Health and Disability Green Paper (2021), pp.

10-13

57

OECD, Sickness, Disability and Work – Breaking the Barriers

(2010), p. 14

Page 20 of 46

There is a growing evidence base about the key

elements of support needed to help employees with

health conditions to remain in work:

· Active management of sickness absence, early

intervention and multidisciplinary support

· Adjustments to the workplace, tasks and hours

· Access to expert-led, impartial advice (e.g. on

capability, return to work planning)

· Time o and adequate income to support recovery.

58

A growing number

59

of businesses are

using Group Income Protection Insurance

to address employee health needs. Group Income

Protection is a product which has been specically

designed to prevent and proactively manage

sickness absence and support returns to work.

Group Income Protection is one solution available to

employers to help them take care of an employee if

an illness or injury threatens their ability to work.

An employer takes out the policy to cover their

promise to provide sick pay to employees if they

are unable to work for a prolonged period because

of illness or injury. Group Income Protection

policies are available to SMEs with as few as three

employees, right through to the largest employers,

and typically provide:

· Personalised and tailored early intervention and

rehabilitation support to help an employee back

to work, aiming to reduce the length of sickness

absence

· Preventative services designed to improve

general employee health and wellbeing, empower

employees to better manage existing health

conditions, or improve line manager capability to

deal with absence and health issues

· A nancial benet if the employee is unable to work

due to illness or injury, meaning that — in addition to

nancial security and peace of mind — the employee

will continue to contribute to society through tax and

National Insurance contributions, and be less reliant

on means-tested state welfare benets.

A Group Income Protection premium is a known

expense that can be budgeted for, providing

certainty for business over costs and ensuring that

employees are protected when absence occurs

regardless of other pressures on the business.

There are also often a range of preventative and

rehabilitation services available as needed, even in

advance of any potential claim against the policy.

Because the support services are arranged by the

insurer, the employer does not face the diculties

of evaluating and procuring them themselves, and

benets from the insurer’s economies of scale.

58

Adapted from HM Government, Health is everyone’s

business: proposals to reduce ill health-related job loss (2019),

pp. 12-13

59

Visavadia, H., ‘Swiss Re: Group risk policies rose 4.1% in

2021’, Cover (20 April 2022)

Page 21 of 46

While many employers are already proactively and

eectively supporting their sta at work, there are wide

variation in employers’ capability across the UK, with

smaller employers typically at a particular disadvantage.

This is often because smaller employers are more likely to:

· Lack time, sta, and capital to invest in expert support

or health interventions

· Be unsure whether the benets of investing in

employee health outweighs the cost

· Have more limited knowledge about their legal

responsibilities surrounding managing sickness

absence

· Have less access to expert advice, such as occupational

health support.

60

Given the positive impact that services like Group

Income Protection can have, the importance of

employers playing a greater role in supporting

employees in returning to work is clear. However,

employers will only be engaged in these types of

activities where there is an incentive for them to do

so. The government believes that too low a rate of sick

pay undermines the economic incentive for employers

to invest in reducing absence.

61

Even putting aside the

low rate of SSP, the current system is also only focused

on prescribing payments. It also does not encourage

or guide employers to provide comprehensive and

eective sickness absence management support.

Reform of SSP has the potential to strengthen

employer incentives to reduce levels of sickness

absence. Insurance models oer a way to pool risks

and resources with other rms, and allow even the

smallest employers to access a comprehensive package

of support which has a strong track record of improving

absence outcomes. Insurance models have also been

shown internationally to improve absence levels over

time through ‘experience rating’ — in the Netherlands,

this eect reduced disability benet onows an

estimated 15%.

62

At a population level, anything

approaching this scale of impact in the UK would be

strongly positive for a whole range of economic, health

and social outcomes.

60

Adapted from HM Government, Health is everyone’s

business: proposals to reduce ill health-related job loss (2019),

pp. 14-15

61

HM Government, Health is everyone’s business: proposals to

reduce ill health-related job loss (2019), pp. 34-35

62

Koning, P. and Lindeboom, M., ‘The Rise and Fall of

Disability Insurance Enrolment in the Netherlands’ in

Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 29, No. 2 (2015), p. 159

Page 22 of 46

It is clear that the current system is not working for our

economy, for our health or for our society.

To help us design a more eective system, we need

to be clear about what we want to achieve. As part of

our research, we held discussions with a wide range of

stakeholders. Based on what we heard, we believe that

a new system needs to deliver ve key criteria in order

to succeed:

Targeted safety net: The rate of sick pay

needs to be sucient to ensure that those

who are unable to work due to sickness

are protected from poverty and insecurity,

while encouraging a return to work where possible.

Diering employer capabilities mean a new system

needs to provide a responsible baseline, rather than an

overly prescriptive solution.

Employer action: The workplace is vital

for addressing the UK’s levels of sickness

absence. Maximising the role of employers

needs to be at the heart of future sick pay

policy as a result. This needs to be delivered through a

mixture of incentives and support for businesses.

Business benet: The system needs to

support a globally competitive economy

and businesses, meaning that it must work

for employers as much as it works for

employees. That means that it should help reduce costs

to business and the wider economy, as well as support

hiring, investment and innovation.

Exchequer benet: Reform needs to

improve the UK’s scal position, by

increasing tax revenue and reducing

spending on means-tested benets.

Financial support to businesses from Government

should minimise the potential for deadweight loss.

Broad support: Reform should forge a

new political consensus and appeal to

a range of stakeholders across society,

much in the same way as reforms to the

private pensions system that arose from the Turner

Commission.

OUR FIVE SUCCESS CRITERIA

Page 23 of 46

Changing SSP alone will not be enough

Given the signicant issues with the current system of SSP, it is no surprise that

many have called for tweaks to the current system. Some of the previously suggested

proposals have been highlighted in past government consultations.

63

These ideas oer

improvements on the current system, but none satises our ve criteria or creates the

step change impact needed to tackle UK sickness absence.

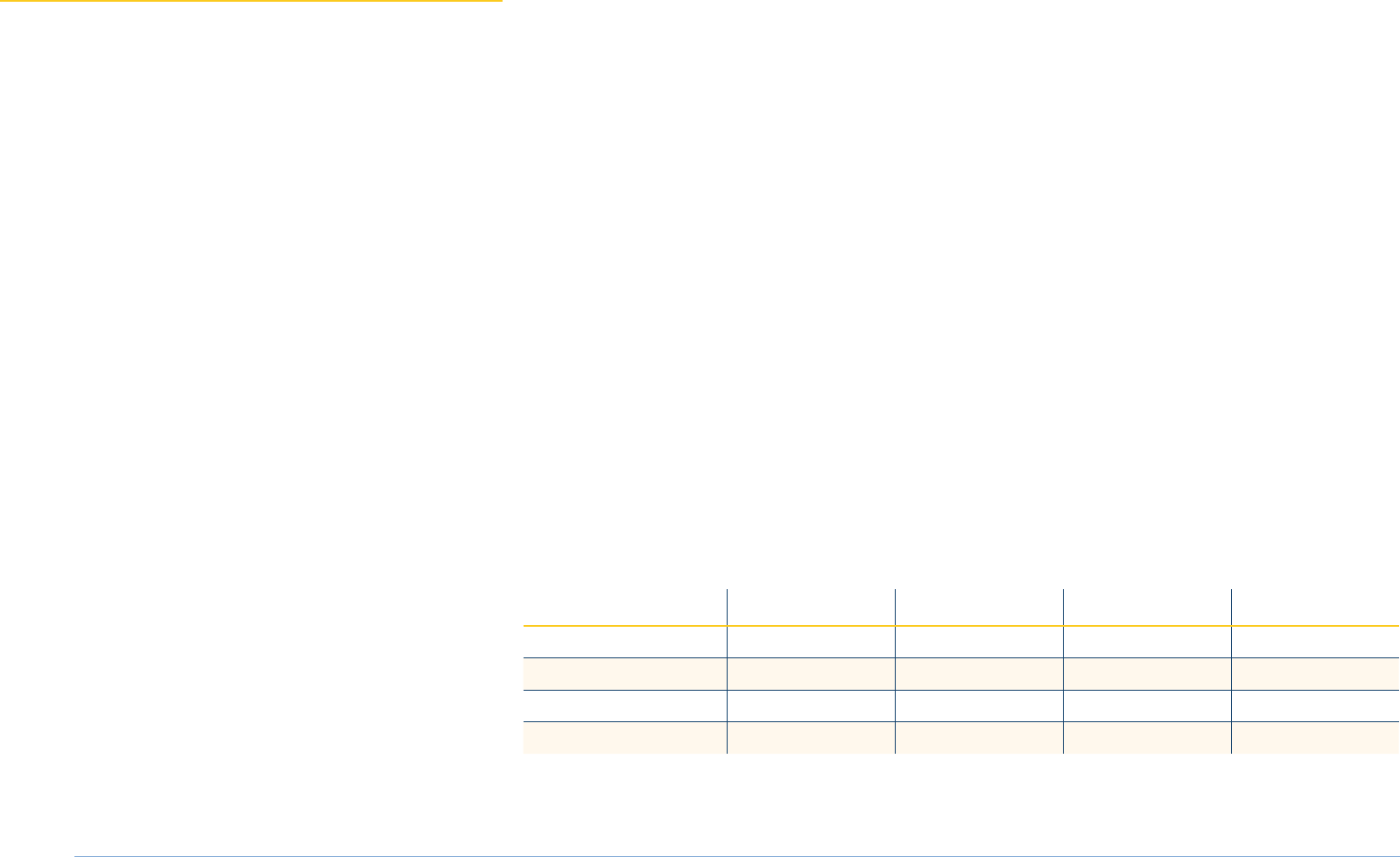

Analysis of selected existing proposals for SSP reform

64

OUR FIVE SUCCESS CRITERIA

Impact of change Numbers aected Cost to business Commentary

Remove

waiting

days

Sick pay payable

from day 1 of

absence

Doubles the

number of SSP-

eligible days to

around 36 million

Up to £500

million

Extends support to those with short spells of absence.

Increases costs for businesses — but does little to

incentivise companies to provide more support to

those with longer spells of absence (costs for these

employees would be unaected)

Replacement rate still very low

Remove

time limit

Allows for very

long-term SSP

beyond 28 weeks

Low — few spells

last this long

Less than £100

million

No additional early intervention incentive and no

increase to support before 28 weeks

Replacement rate still very low

Increasing

exibility

Allows ‘phased

returns’ to work

(i.e. part-wages,

part-SSP).

Unknown — but

likely moderate

Likely to be low Helpful in supporting those transitioning back to

work or managing uctuating conditions

Limited additional incentive for employers to improve

support

Replacement rate still very low

Paid at

National

Living

Wage

SSP paid to

eligible sta at

NLW rate

All those currently

receiving SSP

Also brings into

scope many

currently handled

by OSP schemes

Up to £1 billion May increase incentives for rms to invest in absence

support, but rate increase alone does not guarantee

this. Could create ‘perverse incentives’.

63

HM Government, Health is everyone’s business: proposals to

reduce ill health-related job loss (2019), pp. 25-35

64

WPI Economics, 2022, Statutory Sick Pay: modelling costs

and reforms

Page 24 of 46

Each of these options oers some improvement on the current SSP system, but in

isolation most are unlikely to have a signicant positive impact on return-to-work

outcomes or levels of protection for sick employees, with the exception of increasing the

rate to match the National Living Wage.

This would represent a signicant increase in employee protection but comes at a total

direct employer cost of around £1 billion a year.

65

Without mitigation of these costs and

the provision of signicant return to work support, it is unlikely that such a business

burden would be desirable or politically feasible.

The same is true when implementing all the above options together as a package. This

option would improve living standards and provide more exible nancial support,

plus deliver Exchequer savings. However, the combined cost would be high, and such

a package oers little support for businesses to improve return to work outcomes. We

judge this package to oer little direct business benet, and so it also does not meet our

ve success criteria.

OUR FIVE SUCCESS CRITERIA

Assessment of current system and package of selected SSP reforms against success criteria

Current

SSP system

Package of selected

SSP reforms

Targeted safety net Very poor Moderate

Employer action Very poor Moderate

Business benet Moderate Poor

Exchequer benet Poor Adequate

Broad support Very poor Poor

65

Ibid

Page 25 of 46

to secure widespread support from the business

To bring about the scale of change needed in our

system, changes to the system of SSP payments need to

be partnered with a wider system of proactive support

that makes it easier for employers and employees to

work together to secure a sustainable return to work

where possible.

To be successful, a new system needs to consider

questions relating to:

· Payment: Who gets paid, how much, and by whom/

what mechanism

· Support: Both for employers and employees to

prevent sickness absence and to manage health issues

proactively and eectively if they arise.

Elements of design

Payment Support

Design questions

Who gets

paid?

How

much?

By

whom?

For the

employee

For the

employer

Benets of reform

Higher

productivity,

reduced

worklessness,

increased

retention

Higher living

standards

while o sick

Higher pay,

increased

wellbeing

Better chance

of returning

to work

Short term Long term

Page 26 of 46

Payment

A new system must consider three issues:

· Who is eligible

· How much they get paid

· Who pays them.

Who is eligible?

The current system was designed for a dierent era,

when workers were more likely to receive their week’s

wages in cash and without the diversity of working

practices and hours that characterises today’s labour

market. A new system should be easier and fairer, while

controlling employer costs and minimising legislative

complexity for policymakers.

Under our proposal:

Eligibility is enhanced: By extending

eligibility to include workers with earnings

below the Lower Earnings Limit of £123

per week, around 2 million more workers

(70% of them women)

66

would gain protection in the

event of sickness that they currently lack today. This

policy is supported by the Trades Union Congress and

Federation of Small Businesses.

67

Flexibility is built in: By shifting to an hourly

rather than weekly calculation, and allowing

sick pay and regular earnings simultaneously,

the system will easily take account of part-

time or exible working. Employees will have the option of

a ‘phased return’ to work, which can be make a return to

work more sustainable and successful.

Calculation is simpler: The existing concept

of ‘qualifying days’ makes calculating sick

pay for employees with working patterns

that change week to week very dicult.

The new system could do away with this anachronism

entirely with no adverse eects.

Waiting days remain: While there is a

strong argument for extending eligibility

forwards to the rst day of sickness

absence, in practise this approach would

be inordinately expensive as the vast majority of spells

last for fewer than 4 days. On balance, we believe that

maintaining waiting days is the right approach for now,

but this could be revisited later.

Length of entitlement remains: Although

extending sick pay beyond the current

28 weeks appears to provide greater

employee protection at little overall cost,

there are a number of issues with this approach. While

the overall business cost is low, individual businesses

could see unfortunate and unavoidable ‘peaks’ of very

long-term, very expensive absence. At the same time,

changes to SSP duration have knock-on impacts to

the welfare system, and this would likely mean long

consultations and dicult legislative change.

66

TUC, TUC accuses government of abandoning low-paid

workers after it ditches sick pay reforms (2021)

67

FSB, FSB and TUC call on Chancellor to deliver sick pay for all

(2022)

Page 27 of 46

The generosity of sick pay has a number of important

rst and second order eects. Put simply, low rates

of sick pay (as in the current system) help to control

employer costs at the expense of protections for sick

employees, while for higher rates of sick pay the reverse

is true. The second order eects are more complicated.

As seen in the previous chapter, the current system’s

low at rate has a negative Exchequer impact through

increased spending on means-tested benets, and could

aect value judgements for employers about the benets

of increased investment in absence management.

The mechanism by which to set a new rate presents its

own challenges. A at rate is the simplest to administer

and can eectively control costs, but — as now — carries

the risk of creating undesirable outcomes for certain

workers depending on where it is set. A percentage

replacement rate could deliver a more appropriate safety

net for dierent groups, but costs could spiral if not

capped. Without a ‘oor’, some workers would receive a

lower level of protection than they have today, which is

likely not to be politically acceptable. These options are

considered in more detail below.

Option 1 — Paid at Minimum Wage

One common suggestion is to simply increase the level

of sick pay to the equivalent of the hourly rate of the

applicable National Minimum Wage or National Living

Wage. This is administratively straightforward and

increases worker protection substantially.

However, most people earning below £20,000 a year

would see a replacement rate of 100% under such a

system, and this creates the risk of a ‘moral hazard’

eect which is likely to undermine the acceptability of

such a policy to businesses. The cost for employers

would be, as a minimum, around £700 million a year.

Assuming that all the costs were borne by employers,

there would be Exchequer savings through reduced

social security payments and increased taxes of around

£220 million a year.

68

68

WPI Economics, 2022, Statutory Sick Pay: modelling costs

and reforms

Page 28 of 46

Replacement rate of ‘NLW-equivalent rate’ proposal vs. present system (%)

Reform replacement rate (%) Current SSP replacement rate (%)

Replacement Rate

Source: WPI Economics modelling

Weekly sick pay under ‘NLW-equivalent rate’ proposal vs. present system (£)

Reform payment Current SSP (£)

£ per week SSP

Source: WPI Economics modelling

Annual salary

£48,100

£45,500

£42,900

£40,300

£37,700

£35,100

£32,500

£29,900

£27,300

£24,700

£22,100

£19,500

£16,900

£14,300

£11,700

£9,100

£6,500

£3,900

£1,300

Annual salary

£48,100

£45,500

£42,900

£40,300

£37,700

£35,100

£32,500

£29,900

£27,300

£24,700

£22,100

£19,500

£16,900

£14,300

£11,700

£9,100

£6,500

£3,900

£1,300

0

100

200

300

400

0

100

200

300

400

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

0

20

40

60

80

100

Replacement rate of ‘NLW-equivalent rate’ proposal vs. present system (%)

Reform replacement rate (%) Current SSP replacement rate (%)

Replacement Rate

Source: WPI Economics modelling

Weekly sick pay under ‘NLW-equivalent rate’ proposal vs. present system (£)

Reform payment Current SSP (£)

£ per week SSP

Source: WPI Economics modelling

Annual salary

£48,100

£45,500

£42,900

£40,300

£37,700

£35,100

£32,500

£29,900

£27,300

£24,700

£22,100

£19,500

£16,900

£14,300

£11,700

£9,100

£6,500

£3,900

£1,300

Annual salary

£48,100

£45,500

£42,900

£40,300

£37,700

£35,100

£32,500

£29,900

£27,300

£24,700

£22,100

£19,500

£16,900

£14,300

£11,700

£9,100

£6,500

£3,900

£1,300

0

100

200

300

400

0

100

200

300

400

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

0

20

40

60

80

100

Option 2 — Static replacement rate of 60%

An alternative approach, akin to a ‘Continental’ style social

security system, is to target a given replacement rate,

paying sick employees a set proportion of their normal

salary. This allows living standards to be supported while

retaining ‘work incentive’ eects and avoiding moral

hazard. Typical European replacement rates average 50%-

70%

69

, and similar rates are seen in insurance products.

70

This approach would also be relatively simple. However,

it would be a big departure from the current system

in that statutory payments linked to someone’s salary

could continue all the way up the income scale, meaning

those on higher incomes could receive far higher levels

of sick pay than today — at a concomitant business

cost. Additional business costs would be around £700

million a year.

71

At the same time, workers at the lower end of the

income distribution could actually see their level of

protection decline — those earning just above the

Lower Earnings Limit in the present system (quite often

people working part-time in jobs earning the National

Living Wage) would see the biggest drop.

With some of the UK’s poorest workers losing out

under such a scheme, and the majority of the benets

accruing to those with salaries of over £25,000, this

option is unlikely to garner cross-party support or be

endorsed by trade unions. At a replacement rate of

60%, we estimate Exchequer savings through reduced

social security payments and increased taxes of about

£150 million a year.

72

Replacement rate of 60% vs. present system

Reform replacement rate (%) Current SSP replacement rate (%)

Replacement Rate

Source: WPI Economics modelling

Weekly sick pay under ‘60% replacement rate’ proposal vs. present system (£)

Reform payment(capped) Current SSP (£)

£ per week SSP

Source: WPI Economics modelling

Annual salary

£48,100

£45,500

£42,900

£40,300

£37,700

£35,100

£32,500

£29,900

£27,300

£24,700

£22,100

£19,500

£16,900

£14,300

£11,700

£9,100

£6,500

£3,900

£1,300

Annual salary

£48,100

£45,500

£42,900

£40,300

£37,700

£35,100

£32,500

£29,900

£27,300

£24,700

£22,100

£19,500

£16,900

£14,300

£11,700

£9,100

£6,500

£3,900

£1,300

0

100

200

300

400

500

600

0

100

200

300

400

500

600

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

0

20

40

60

80

100

69

TUC, Welfare States: How generous are British benefits

compared with other rich nations? (2016), p. 28

70

MoneyHelper, What is income protection insurance? (2022)

71

WPI Economics, 2022, Statutory Sick Pay: modelling costs

and reforms

72

Ibid

Page 30 of 46

Option 3 — Targeted Support

The above options highlighted the challenges posed by

simplistic solutions and led us to the conclusion that the

rate needed to achieve three objectives:

· Achieving replacement rates of between 50% and 70%

for most workers

· Acting as true safety net, oering the greatest protection

to workers on the lowest earnings who are the least

likely to be covered by occupational sick pay schemes

· Avoiding seeing low-paid workers lose out as a result

of the new system.

To do this, we propose a new rate based on:

· A universal standard allowance based on the NLW

up to 10 hours of work, pro-rated for the number of

days o sick — meaning that those on extremely low

incomes see very high replacement rates, and there

are no losers compared to the current SSP system

· A top-up replacement rate providing 35% of weekly pay

on top of the standard allowance, again pro-rated for the

number of days o sick, resulting in gross replacement

rates for those earning up to £30,000 that exceed 40%

· A weekly cap on costs set at £250 to ensure that

costs are managed and that the system is focused on

a statutory minimum, rather than trying to replace

occupational schemes that are regularly provided for

those on higher salaries.

Replacement rate of 60% vs. present system

Reform replacement rate (%) Current SSP replacement rate (%)

Replacement Rate

Source: WPI Economics modelling

Weekly sick pay under ‘60% replacement rate’ proposal vs. present system (£)

Reform payment(capped) Current SSP (£)

£ per week SSP

Source: WPI Economics modelling

Annual salary

£48,100

£45,500

£42,900

£40,300

£37,700

£35,100

£32,500

£29,900

£27,300

£24,700

£22,100

£19,500

£16,900

£14,300

£11,700

£9,100

£6,500

£3,900

£1,300

Annual salary

£48,100

£45,500

£42,900

£40,300

£37,700

£35,100

£32,500

£29,900

£27,300

£24,700

£22,100

£19,500

£16,900

£14,300

£11,700

£9,100

£6,500

£3,900

£1,300

0

100

200

300

400

500

600

0

100

200

300

400

500

600

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

0

20

40

60

80

100

Page 31 of 46

This option achieves our three objectives to provide targeted and eective support.

Around 60% of the benets would be accrued by those on salaries of less than £25,000

a year. It also comes at a substantially lower cost to businesses than either an enhanced

at rate or static replacement rate option, at an additional cost of around £400 million.

73

Direct Exchequer savings (before any behaviour change) through reduced social security

payments and increased taxes would be about £120 million a year. On top of these, WPI

Economics modelling projects further savings of at least £500 million a year because of

reduced incidence of sickness absence, and fewer people falling out of work and onto

sickness and disability benets.

74

Replacement rate of ‘targeted support’ proposal vs. present system (%)

Reform replacement rate (%) Current SSP replacement rate (%)

Replacement Rate

Source: WPI Economics modelling

W

eekly sick pay under ‘targeted support’ proposal vs. present system (£)

Reform payment Current SSP (£)

£ per week SSP

Source: WPI Economics modelling

Annual salary

£48,100

£45,500

£42,900

£40,300

£37,700

£35,100

£32,500

£29,900

£27,300

£24,700

£22,100

£19,500

£16,900

£14,300

£11,700

£9,100

£6,500

£3,900

£1,300

Annual salary

£48,100

£45,500

£42,900

£40,300

£37,700

£35,100

£32,500

£29,900

£27,300

£24,700

£22,100

£19,500

£16,900

£14,300

£11,700

£9,100

£6,500

£3,900

£1,300

0

50

100

150

200

250

0

50

100

150

200

250

Reform payment

Current SSP (£)

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

0

20

40

60

80

100

Reform replacement rate (%)

Current SSP replacement rate (%)

73

Ibid

74

Ibid

Page 32 of 46

Discussing each of the proposed options for rate reform reveals that the status quo

represents the worst of all worlds: low levels of worker protection, limited employer

incentives and high (largely hidden) taxpayer costs. Our third option provides targeted

support at a controlled cost.

Replacement rate of ‘targeted support’ proposal vs. present system (%)

Reform replacement rate (%) Current SSP replacement rate (%)

Replacement Rate

Source: WPI Economics modelling

W

eekly sick pay under ‘targeted support’ proposal vs. present system (£)

Reform payment Current SSP (£)

£ per week SSP

Source: WPI Economics modelling

Annual salary

£48,100

£45,500

£42,900

£40,300

£37,700

£35,100

£32,500

£29,900

£27,300

£24,700

£22,100

£19,500

£16,900

£14,300

£11,700

£9,100

£6,500

£3,900

£1,300

Annual salary

£48,100

£45,500

£42,900

£40,300

£37,700

£35,100

£32,500

£29,900

£27,300

£24,700

£22,100

£19,500

£16,900

£14,300

£11,700

£9,100

£6,500

£3,900

£1,300

0

50

100

150

200

250

0

50

100

150

200

250

Reform payment

Current SSP (£)

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

0

20

40

60

80

100

Reform replacement rate (%)

Current SSP replacement rate (%)

Page 33 of 46

Though the least burdensome, the rst order costs for business presented by Option 3

do present a hurdle to securing broad support, and so it is important to consider how

changes to the rate of sick pay interact with other elements of the proposed policy

design, and the wider existing policy landscape. This means considering of who pays,

and the package of business support available.

The system of employers being responsible for the administration and payment (transfer

of funds) of sick pay has worked well, and we do not propose fundamentally changing this.

However, the question of who bears the ultimate cost of sick pay is an important one.

Employers bearing a higher proportion of sick pay costs increases burden on business,

but brings Exchequer benets in the form of reduced spending on means-tested benets

and increased tax receipts. Alternatively, the government could choose to bear some or

all of the costs of sick pay, though this is likely to have a detrimental scal impact.

Assessment of rate reform options against key success criteria

Current

SSP system

Option 1 —

Minimum Wage

Option 2 —

Replacement Rate

Option 3 —

Targeted Support

Targeted safety net No Unbalanced Unbalanced Balanced

Employer action No Some Some Some

Exchequer benet Limited Good Good Good

Broad support No Unlikely Unlikely Possible

Page 34 of 46

We have considered four potential approaches to this question.

1. 100% employer-funded: This option sends a strong signal to businesses that they

must act. It substantially increases employer costs without state support.

2. 100% state-funded: A big departure from the current system, this option would

increase taxpayer costs signicantly. Some would argue this could reduce employers’

incentives to manage sickness absence eectively. This option would likely need to

be accompanied by a highly prescriptive system governing absence management to

reduce taxpayer spending.

3. Employer-funded, with targeted state support: This option would see the Exchequer

redeploy some of the savings it makes through reduced social security payments

and increased tax take under a more generous employer-funded system to give

substantial help to businesses needing the most support to improve their workplace

health programme.

4. Employee contribution: This option would see employees contribute from their salary

to fund an enhanced sick pay system. Given the current political and economic climate,

and the present high burden of taxation, this option is unlikely to be politically feasible.

Assessment of suitability of funding models against key success criteria

100%

employer-funded

100%

state-funded

Employer-funded

with state support

Employee

contribution

Employer action High Low High Unknown

Business benet Moderate High High Moderate

Exchequer benet High Low High Moderate

Broad support Unlikely Unlikely Possible Unlikely

Page 35 of 46

Support

We have demonstrated the benets of a reformed rate that provides targeted support

for employees at the lower end of the income distribution while still lifting the minimum

level of protection for all workers and strongly incentivising proactive sickness absence

management. At the same time, we believe there needs to be targeted support for

employers to help them meet this challenge and the costs of improving the help and

support they are able to oer their sta.

Given the scale of the policy challenge and the modelled Exchequer savings from a

reformed rate of sick pay, £500 million should be unlocked to level up the health of

employees in SMEs across the UK.

75

There is a strong and growing international and

domestic evidence base supporting a wide range of workplace health interventions. In

the UK, the government is supporting this work by its joint Work and Health Unit, which

by mid-2018 had already launched projects to improve workplace health and disability

employment worth around £1 billion.

Page 36 of 46

Stakeholders consulted as part of our research raised

a range of potential routes forward. A brief discussion

of these can be found below, and is followed by our

preferred package.

76

1. Unconditional employer rebate: This option

would see costs fully or partially rebated to SMEs

or particular sectors that could be impacted more

strongly by increases in sick pay. While it would be

eective in supporting businesses to deal with sick

pay costs, spending could quickly hit or outpace

available funding, and some would argue it could

act to diminish the incentives of employers to take

eective action to better manage sickness absence.

This option would not most eciently target public

funds towards eecting business action.

2. State-funded support service: This option would

use the money to create a publicly funded service

(likely digitally delivered) to provide advice and

support to employers to help them manage sickness

absence better. It might also act as a ‘gateway’ to

claim a conditional rebate of sick pay costs. Some

local authorities run similar services today. The

government previously ran a national service called

Fit for Work, but this saw very low take-up from

employers. Any new state-funded support service

would therefore need to overcome the challenges Fit

to Work faced.

3. Conditional employer rebate: This option would

provide a targeted rebate of sick pay costs to

employers who were able to demonstrate they were

eectively managing sickness absence. There are

a range of approaches to this, including a rebate

conned to a particular employee’s absence journey,

such as where it can be demonstrated that the

employer has supported the employee through

interventions such as a return-to-work plan. It may

also occur at an organisational level, for instance by

rebating sick pay costs incurred by businesses which

meet certain prescribed standards. However such a

scheme was designed, it would need to both deliver

eective behaviour change among employers while