Is This a Good Quality Outcome Evaluation Report?

A Guide for Practitioners

Justice Research and

Statistics Association

Is This a Good Quality Outcome Evaluation Report?

A Guide for Practitioners

A project of the Justice Research and Statistics Association

777 North Capitol Street, NE, Suite 801

Washington, DC 20002

(202) 842-9330

http://www.jrsa.org

BJA Center for Program Evaluation and Performance Measurement

http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/BJA/ evaluation/index.html

2

Acknowledgments

This document was written by Justice Research and Statistics

Association staff members Mary Poulin, Stan Orchowsky, and

Jason Trask under the Bureau of Justice Assistance Center for

Program Evaluation and Performance Measurement project.

Edward Banks of the Bureau of Justice Assistance supported

the development of this publication.

November 2011

The Bureau of Justice Assistance Center for Program Evaluation and

Performance Measurement project is supported by Grant No. 2010-D2-

BX-K028 awarded by the Bureau of Justice Assistance. The Bureau of

Justice Assistance is a component of the Office of Justice Programs,

which also includes the Bureau of Justice Statistics, the National Insti-

tute of Justice, the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Preven-

tion, and the Office for Victims of Crime. Points of view or opinions

in this document are those of the authors and do not represent the

official position or policies of the United States Department of Justice.

3

Is This a Good Quality Outcome Evaluation Report?

This guide is designed to introduce and explain the key concepts

in outcome evaluation research in order to help practitioners

distinguish between good and poor quality evaluation reports.

The intent is to help practitioners 1) understand key evaluation

terms and designs, and 2) recognize how to identify a well-

written evaluation report. This guide does not explain how to

identify evidence-based programs or “what works.” It is not

intended to assist the reader with making overall judgments or

determinations about specific programs or program types. More

information than is found in one evaluation report is needed to

identify whether a program is evidence-based. This guide pro-

vides the reader with the basic information needed to identify

high quality evaluation reports.

What Is Evaluation?

Evaluation is a systematic and objective process for determining

the success or impact of a policy or program. Evaluation is usually

considered a type of research and consequently uses many of

the same approaches (i.e., research designs). Research typically

asks questions about why or how something operates.

Evaluation addresses questions about whether and to what

extent the program is achieving its goals and objectives and the

impact of the intervention. A good evaluation has several distin-

guishing characteristics relating to focus, methodology, and

function. Evaluation: 1) assesses the effectiveness of an ongoing

program in achieving its objectives, and 2) through its design,

helps to distinguish the effects of a program or policy from

those of other forces that may cause the outcomes. With this

information, practitioners can then implement program

improvements through modifications to the current program

model or operations.

Evaluations are generally categorized as being either process or

outcome. Process evaluations focus on the implementation of

4

the program or project. They may precede an outcome evalua-

tion and can also be used along with an outcome evaluation to

ensure that the program model or elements are being imple-

mented with fidelity (i.e., consistent with the model). Outcome

evaluations (sometimes called impact evaluations) focus on the

effectiveness of a program or project. This guide concerns

itself with outcome evaluations and how to tell whether

they are of high quality.

Evaluations vary widely in quality. While most people

understand this, fewer are comfortable with determining

which are of high quality. Reading an evaluation report,

particularly one that is full of statistics and technical

terminology on research methods, can be overwhelming.

Indeed, full understanding requires advanced education

in research methods. Nevertheless, there are some key

issues that anyone can use to help distinguish between

good and poor evaluations. These issues are addressed in

this guide.

Issue 1: The Role of Evaluation Design

The basic question an evaluation asks is, did the program/policy

have the intended effect? There are many ways to go about

trying to answer this question. The research design is the most

important piece of information to use in assessing whether the

evaluation can answer this question.

To assess the effect of a program through an outcome evalua-

tion, an evaluator must establish that a causal relationship exists

between the program and any outcome shown. In other words,

did the program (cause) lead to the outcome (effect)? In order

to demonstrate a causal relationship between the program and

the outcome, the evaluator must show: 1) that the cause pre-

ceded the effect, 2) the cause and effect are related to each

other, and 3) that the effect was not caused by an outside factor.

Often, statements about the relationship between a program

and outcomes are not warranted because the design of the

There are

some key

issues that

anyone can

use to help

distinguish

between

good and

poor quality

evaluations.

5

evaluation does not take into account external factors that may

be responsible for the outcomes. For example, the reduction of

drug use by offenders in a particular state could be influenced

by the program that intends to reduce drug use as well as by

external factors, such as the availability of drugs due to law

enforcement actions or the fear of imprisonment due to change

in legislation regarding drug use (see Figure 1).

Evaluators may choose from many different designs to try to

demonstrate causality. Some of these designs are better than

others for demonstrating causality. Factors like resources to do

the evaluation (time and money), and concerns about the ap-

propriateness of an approach given what the program is trying

to accomplish usually play a big role in what approach is

selected. The sections below discuss some of the most common

approaches used in criminal justice. The way in which an evalua-

tor can demonstrate that a causal relationship exists is through

the evaluation design, that is, the structure of the evaluation.

Evaluation designs are commonly divided into three major

categories based on their characteristics: 1) experimental,

2) quasi-experimental, and 3) non-experimental.

Figure 1. Possible Factors Affecting Outcomes of Drug Use Reduction Program

Availability

of Drugs

Fear of

Imprisonment

OutcomesProgram

6

Experimental Designs: Confidence in Results

Experimental designs are distinguished by the random assignment

of subjects into treatment (i.e., received the program or policy)

and control (i.e., did not receive the program or policy) groups.

They are often referred to as the “gold standard,” because with

random assignment to either group (to do random assignment,

envision flipping a coin to decide who goes into each group) it is

assumed that the only difference between the two

groups is that one group had the treatment and the

other did not. The term “randomized control trial” (RCT)

is often used to refer to an experimental design.

With this design, individuals are randomly assigned into

either the treatment or the control group, the interven-

tion is delivered to the treatment group, and outcomes

for each group are compared. Though designs will vary

from experiment to experiment, a common variation on

this design is that the same data are collected for each

group before the intervention (pre-test) and again after

the intervention (post-test). The evaluator examines

whether there are differences in the change from the

pre-test to the post-test for each group.

The reason this design is considered to be so strong is because

of how, when, and for whom data are collected. There is little

question about whether the program/policy caused the change

because this approach controls for external factors. External

factors are factors other than the program/policy that may have

caused the outcomes. For example, what if there was a change

in police response to drug sales during the time that a drug

prevention program was operating? This change could provide

plausible alternative explanations for an increase or decrease in

arrests for drug sales. An experimental design would address a

concern such as this, since prevention program participants and

non-participants would both be exposed to the changed police

response.

It is important

that the

evaluator

try to control

for factors

outside of the

program or

policy that

may be

responsible

for the

outcomes.

7

Of course, to have this confidence requires that the design is

implemented well. Evaluators must ensure that: 1) assignment

to the treatment and control groups is actually random (e.g., de-

ciding to put all high-risk offenders in the treatment group, but

randomly putting others in the treatment and control groups is

not random assignment), 2) the control group does not receive

the intervention, and 3) the evaluation examines outcomes for

everyone, even those in the treatment group who don’t finish

the intervention. A good evaluation report on

an experimental design should discuss these

issues.

Quasi-Experimental Designs: Common in

Criminal Justice

The major difference between experimental

designs and quasi-experimental designs

relates to the use of a control group. Quasi-

experimental designs may or may not use a

control group (usually called comparison

groups in quasi-experiments). If a quasi-experi-

ment uses a control group, individuals/cases

will not be placed randomly into the groups.

The comparison group simply consists of a

group of individuals/cases that are considered

similar to those who received the treatment.

The evaluator may attempt to ensure compa-

rability between the two groups by matching the individuals in

the groups on factors that are considered relevant, such as age,

gender, or prior history with the criminal justice system. For ex-

ample, if gender and prior criminal justice history are considered

relevant factors, one way to match is to ensure that the treatment

and comparison groups have similar proportions of males and

subjects without previous arrests. If one group had more indi-

viduals without previous arrests, then its members may be less

likely to commit crime than the members of the other group.

The more confident we can be that the two groups are similar in

all key characteristics other than program participation, the

Given the program or policy

under study, it may be diffi-

cult to identify an appropri-

ate comparison or control

group. In criminal justice

this is particularly the case

with programs/policies that

affect an entire community

or jurisdiction. Keep this in

mind when considering the

strength of the design. Always

look for an explanation of

why the evaluator chose a

particular research design.

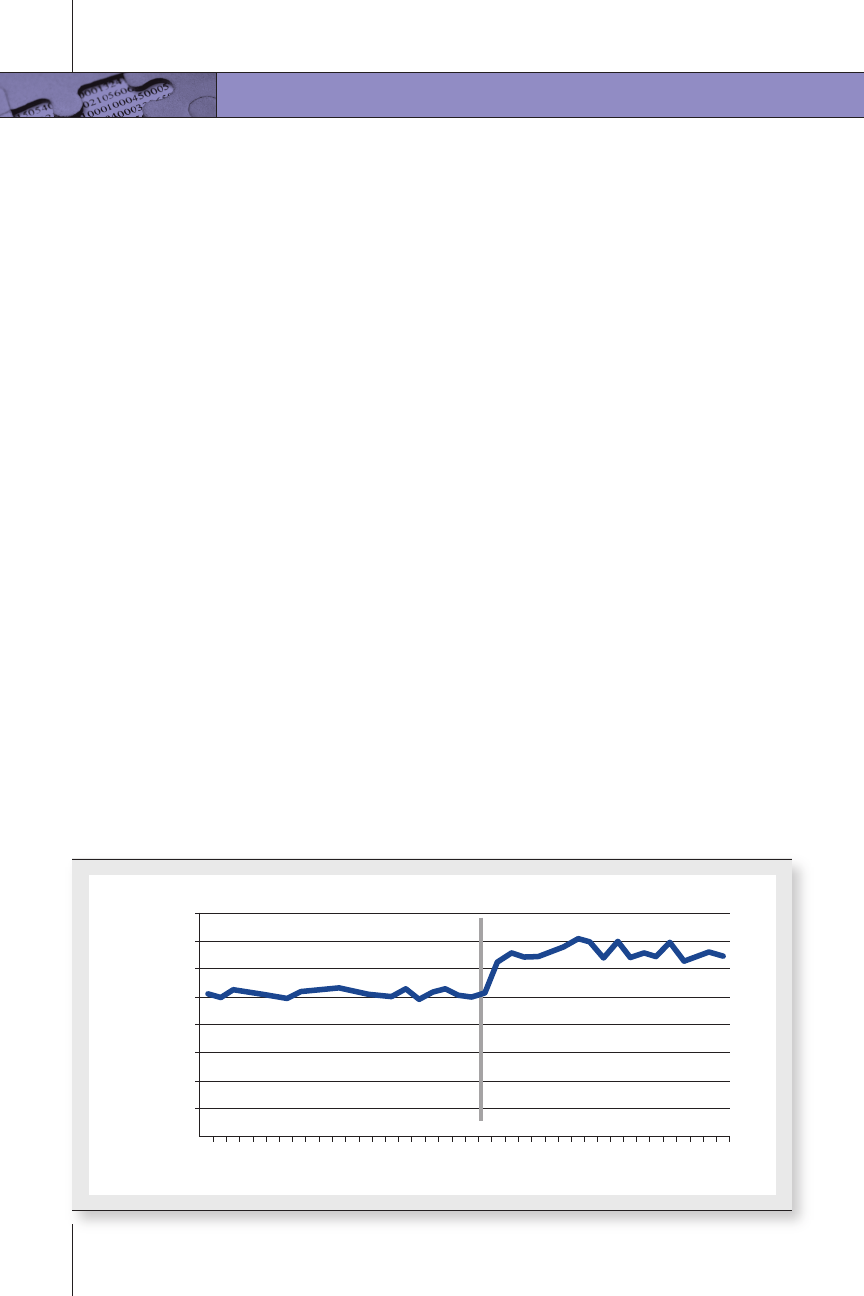

Figure 2. Example of Data Presentation for Time Series Analysis

Number of Arrests

Month

Number of Arrests by Month

160

140

120

100

80

60

40

20

0

1 3 5 7 9 11 13 15 17 19 21 23 25 27 29 31 33 35 37 39

Date of Intervention

8

more confident we can be that the program caused any observed

differences in outcomes.

As with experiments, designs of quasi-experiments will vary, but

perhaps the most common quasi-experimental design used in

evaluation is a pre-post design with a comparison group. In this

design, the same data are collected for each group before the in-

tervention (pre-test) and again after the intervention (post-test).

The evaluator examines whether there are differences in the

change from the pre-test to the post-test for each group.

Another commonly used quasi-experimental design in criminal

justice is the time series analysis. With this method an evaluator

typically studies something like the effect of a new policy or leg-

islation in a jurisdiction. The evaluator conducts a series of ob-

servations prior to the new policy, then conducts another series

of observations following the implementation of a policy. Let’s

say that certain legislation was expected to increase the number

of arrests. The evaluator may look at the number of arrests for

several months preceding the legislation and then several

months following the legislation to see whether a change in the

number of arrests occurred. Figure 2 provides a visual example

9

of how an evaluator may present data in a time series analysis.

The legislation was expected to increase arrests and it appears

to have had that effect; arrests increased over the time exam-

ined. A good time series design would also examine whether

other factors occurring around the time of the new legislation,

say the hiring of additional police officers, appeared to con-

tribute to the number of arrests.

Non-Experimental Designs: Least Amount of Guidance on

Program/Policy Impact

A non-experimental design is the weakest of all the designs and

raises the greatest number of questions about whether the

program/policy caused the outcomes. In this approach, the

evaluator collects data on the group receiving the treatment or

affected by the program/policy at one point only—after the

program/policy occurred. The evaluator is not able to assess

whether change occurred. An example of a non-experimental

design would be a survey of residents to assess satisfaction with

police practices that occurred after the introduction of a new

community policing effort. If the questions address only current

satisfaction, there is no way to know whether satisfaction in-

creased after community policing began, let alone whether

community policing improved satisfaction.

Issue 2: How Well Is the Evaluation Carried Out?

For any design, the evaluator must ensure that the evaluation is

conducted in such a way that the basic design is not undermined

and that other elements of the evaluation, from the data collec-

tion to the analysis and the writing up of the results, are carried

out sufficiently well so that one can trust the results.

Here we discuss the major issues (in addition to the research de-

sign) one needs to identify when assessing how well the evalua-

tion was carried out. It is difficult to say in the limited discussion

provided here at what point the evaluation report should be

considered seriously flawed if one or more of these issues is not

10

addressed. However, the more of these items appropriately ad-

dressed in the evaluation report, the more confidence one

should have in the results.

It is important that the number of subjects (e.g., individuals,

cases, etc.) selected for the study be large enough to support

the analyses required to answer the evaluation questions and to

raise little doubt that the results adequately represent the popu-

lation. (The population is the entire group from which the sam-

ple was drawn.) This issue of sample size sufficiency is important

when issues such as resource constraints do not permit data col-

lection from all subjects affected (i.e., the population) by the

program/policy. Figure 3 provides a simple guide for selecting a

sufficient sample size.

An issue related to sample size

is attrition. Attrition refers to

subjects dropping out of the

evaluation before data collection

has concluded. Attrition is an im-

portant issue because individuals

usually don’t drop out of evalua-

tions randomly; for example,

perhaps offenders with more

serious drug problems are more

likely to drop out of drug treat-

ment programs. One result of

this non-random attrition is that

treatment and comparison

groups that started out looking

similar may not end up that way.

Good evaluation studies track

who drops out, when they drop

out, and (ideally) why they drop

out. The number of subjects who

drop out as well as descriptive

information about the dropouts

Is the Sample Size Appropriate?

Number in Minimum

Population Sample Size

10 10

20 19

50 44

70 59

100 80

150 108

200 127

500 217

1000 278

1500 306

2000 322

Adapted from: Krejcie, R.V., & Morgan, D.W.

(1970). Determining sample size for re-

search activities, Educational and Psycho-

logical Measurement, 30(3), 604–610.

Figure 3. Sample Size

11

should be included in the evaluation report. Outcome informa-

tion should be included on these subjects (e.g., recidivism rate

for dropouts) and should be a consideration in assessing the

sufficiency of the sample size.

Besides attrition, sometimes problems with the implementation

of an evaluation, such as recruitment of subjects for the study or

assignment to the treatment and control groups not occurring

as planned, may result in the treatment group being substan-

tially different on important characteristics from the comparison

or control group (e.g., age of the offender, history of drug use,

geographic residence). The evaluation report should specify the

important characteristics of similarity between the groups and

report on whether the two groups are actually similar on these

characteristics.

The main question in an evaluation of a program/policy deliv-

ered to a group of subjects is usually something like: 1) Did the

group that received the program/policy have better outcomes

than those who did not receive/were not affected by the pro-

gram/policy? or 2) Did the group that received the program/

policy improve/change since the intervention was delivered?

However, when a program/ policy is implemented, it is common

to expect that certain subgroups of subjects will have better (or

worse) outcomes than others. For example, one might reason-

ably expect that individuals completing the program would

have better outcomes than individuals not completing the

program. The evaluation report should indicate whether or not

analyses breaking out outcomes by subgroups were conducted

and the rationale for doing so.

The measures (i.e., the indicators) selected for assessing the

outcomes of the program/policy should fit well with the pro-

gram/policy objectives and should measure the concepts of

interest well. If, for example, the concept of interest is crime,

crime could be measured in different ways, such as the number

of arrests or self-reports of offending. One factor the evaluator

12

considers when deciding how to measure crime is how good of

a job the indicator will do in measuring crime. Evaluators refer

to this as the reliability and validity of the measures. Without

getting overly complex here, the evaluation report should, at

a minimum, explain why the measures were selected, the

process for selecting the measures, and the time frame meas-

ured by the indicator (e.g., whether employment was obtained

within six months of program discharge). When reviewing the

reliability and validity of the measures in the evaluation report,

one should also consider the impact of the data source used for

the measure on the outcome(s). For example, using arrests as a

measure of crime will produce a higher crime count than using

court convictions as a measure of crime. Further, think about

whether the measures used are sufficiently precise. For example,

if the report is an evaluation of a drug treatment program, does

it track drug usage in terms of a) whether or not the offender

used drugs, or b) the number of times the offender used drugs?

Option b would permit an examination of decreases (or in-

creases) in drug use rather than simply the presence or absence

of drug use. Since it is not uncommon for drug users to relapse,

Option b would be a better choice for a drug treatment pro-

gram evaluation.

When looking at the outcomes reported, consider the timing

used for follow-up, if any. For example, an evaluation that has

reported recidivism occurring three months post-discharge

may look more (or less) successful than if the recidivism checks

occurred 12 months post-discharge. Evaluators should account

for why they chose that particular follow-up time and address

the likely implications of using a different follow-up time. The

follow-up time should make sense given the design of the

program, and the time should be comparable for all study

participants. For example, if they used a 12-month follow up

time for recidivism, they should identify and report on when

the recidivism occurred within those 12 months.

Even in an outcome evaluation, the evaluation report should

discuss the extent to which the program was implemented as

13

planned overall (fidelity to pro-

gram design) and for the indi-

vidual subjects (program

dosage). Information like this,

which is typically included in a

process evaluation, is necessary

to determine whether and how

participation in the program

may have had an impact on the

outcomes.

Perhaps one of the areas most

difficult for individuals without

a strong research background

to assess is whether the statisti-

cal tests used were appropriate

and interpreted correctly.

1

As

with the selection of measures,

the evaluation report should

clearly indicate why a particular

statistical test was selected and how it was interpreted. An often

used phrase here is statistical significance. In an evaluation, the

term usually refers to the size of the observed difference(s) be-

tween the program (i.e., treatment) and non-program (i.e., com-

parison or control) groups on the outcome(s) measured. When

the authors note that a finding was statistically significant, they

are saying that the observed difference (whether or not it

showed the program to have the desired result) was large

enough that it is unlikely to have occurred by chance. Without a

statistical test, we cannot know how much importance (signifi-

cance) to place on the size of the effect (presumably) produced

by the program being evaluated. Meta-analyses will report on

the effect size, a standard way of comparing outcomes across

studies to assess the size of the observed difference.

Definitions of Evaluation Terms

• Sample size: the number of

subjects in the study.

• Sufficient sample size: Number of

subjects is large enough that there

is confidence that the results

represent the population being

studied.

• Statistical significance: whether the

program/policy is likely to have

caused the desired result/change.

• Effect size: how much of a change

the program/policy caused.

1

This assumes that the report is a quantitative study, i.e., one that collects numerical data.

14

Beyond the Basics

What About Cost-Benefit Analysis?

After assessing program effectiveness, some evaluators take

an additional step to assess the economic implications of the

program. Cost-effectiveness and cost-benefit analysis (CBA)

are two approaches to doing this. Cost-effectiveness analysis

examines the monetary costs and outcomes of a program. CBA

assesses not only the costs and effects of the program, but also

the benefits. CBA considers whether the benefits outweigh the

costs. For more information on CBA, see the Cost-Benefit Knowl-

edge Bank for Criminal Justice: http://cbkb.org.

Meta-Analyses and Systematic Reviews: A Study of the Studies

Reports of both meta-analyses and systematic reviews synthe-

size the results of studies on a particular topic in order to pro-

duce a summary statement on the question being examined

(e.g., do drug courts reduce substance abuse?). They typically

only include the studies with strong research designs that were

carried out well. These studies are important because they can

be used to determine whether a program is evidence-based.

Similar to other research designs, these two approaches spell

out in advance the procedures they use to compare studies in-

cluded in the analysis. In this way, the approach should be able

to be replicated by others. Though the terms are not necessarily

interchangeable because of the methods used, meta-analyses

and systematic reviews generally have the same purpose. The

methods used in both are quite involved and discussion of the

methods and how to assess the quality of these types of studies

are beyond the scope of this guide, but the reader should be

aware that both meta-analyses and systematic reviews include a

much more complex, thorough, and methodical review of a

study than is conducted by a literature review.

15

Putting It All Together

It takes time to assess the quality of an evaluation report. This

investment of time is worthwhile, however, because knowing

whether a report is of good quality will help with issues that

frequently come up. Why does this evaluator say this program

works, for example, but that evaluator says it doesn’t? The quality

of the evaluation report often contributes to these conflicting

conclusions. Being able to assess the quality of an evaluation

report will help one determine whether conflicting conclusions

are related to the quality of the report.

This guide is by no means comprehensive; there is far more that

can be done to assess an evaluation’s quality. Nevertheless, the

guide should help practitioners make informed decisions about

how much to rely on a particular evaluation.

For more information on research designs see:

• The Campbell Collaboration, What Is a Systematic Review?

http://www.campbellcollaboration.org/what_is_a_system-

atic_review/index.php

• Cochrane Collaboration, Open Learning Material:

http://www.cochrane-net.org/openlearning/html/mod0.htm

• Cost-Benefit Knowledge Bank for Criminal Justice:

http://cbkb.org

• Crime Solutions.gov: http://crimesolutions.gov/

• Guide to Program Evaluation on the BJA Center for Program

Evaluation and Performance Measurement:

http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/BJA/evaluation/guide/index.htm

• The Research Methods Knowledge Base: http://www.socialre-

searchmethods.net/kb/

Is This a Good Quality Evaluation Report?

Issue Response

What is the research design (experimental,

quasi-experimental, non-experimental,

meta-analysis)?

If applicable:

• Did random assignment go as planned?

• Did anyone in the control/ comparison

group receive the intervention?

• Did the evaluation examine outcomes

for program dropouts?

Is the sample size sufficient?

Does the report address attrition well?

Is the comparison/control group comparable

to the treatment group (if applicable)?

Do analyses appropriately examine outcomes

by subgroups (i.e., break out outcomes by

subgroups)?

Are the measures suitable?

Was there a comparable follow-up time for

all evaluation subjects (if applicable)?

Did follow-up time make sense (if applicable)?

Does the report address program implemen-

tation (fidelity and dosage)?

Were statistical tests appropriate and inter-

preted correctly?

16

Using Information from the Guide

The checklist below will help users apply the information provided in the guide

to a particular evaluation. Though the checklist does not provide a final score on

evaluation quality, checklist users can be sure that they have examined the report

for all applicable issues.