1

Report to Congress on Best Practices

Regarding Enforcement of Anti-Stalking Laws

Reporting Requirement

Section 3 of the Combat Online Predators Act (PL No. 116-249) requires the Attorney General to

submit a report to Congress on best practices regarding enforcement of anti-stalking laws, one

year after the date of enactment of the Act. The report is to include an evaluation of federal,

tribal, state, and local efforts to enforce laws relating to stalking;” and “identify and describe

those elements of such efforts that constitute the best practices for the enforcement of such

laws.”

Background

Roughly 1 in 3 women, and 1 in 6 men in the United States have suffered some form of stalking

in the course of their lifetime.

1

Stalking is challenging to police effectively as it is a pattern-based, rather than an incident-

based, crime. Responding to stalking cases often necessitates specialized knowledge and a

significant investigative effort.

2

Research supported by the Department of Justice (DOJ), Office

on Violence Against Women (OVW) suggests that the law enforcement response would be

improved with the implementation of assessment tools for identifying stalking behaviors within

the context of other intimate partner violence (IPV)-based crimes, as well as by providing

specific training for officers.

3

A detailed summary of research, statistics, best practices, and OVW grantees’ efforts related to

stalking can be found in OVW’s reports to Congress pursuant to 34 U.S.C. § 12049, which

requires a report every even-numbered fiscal year to include information about the incidence

of stalking and domestic violence and evaluating the effectiveness of anti-stalking efforts and

legislation. OVW’s reports to Congress are available here:

https://www.justice.gov/ovw/reports-congress.

1

Smith, S. G., Basile, K. C., & Kresnow, M. (2022). The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2016/2017

Report on Stalking. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/nisvs/nisvsstalkingreport.pdf

2

National Institutes of Justice. (2022, February 1). Current State of Knowledge about Stalking and Gender-Based Violence: The

Known, Unknown, and Yet To Be Known [Webinar].

https://nij.ojp.gov/events/current-state-knowledge-about-stalking-and-gender-based-violence-known-unknown-and-yet-be.

3

Garza, A.D., Franklin, C. A., & Goodson, A. (2020). The nexus between intimate partner violence and stalking: Examining the

arrest decision. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 47(8), 1014-1031, available at:

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0093854820931149.

2

Stalking Victimization in the United States

This section contains updated information to reflect federal data on stalking published in 2022

by the DOJ’s Bureau of Justice Statistics and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in a

recent report to Congress submitted pursuant to 34 U.S.C. § 12049. (BJS 2019 and 2022 reports;

CDC NISVS 2022 report)

The Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) reports that approximately 3.4 million people age 16 or

older were stalked in 2019,

4

and the National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey

(NISVS), administered by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), has found that

about 1 in 3 women and 1 in 6 men have experienced stalking at some point in their lives.

5

Women who are divorced or separated face the highest rate of stalking.

6

The majority of

victims are stalked by people they know, and 43.4% of female victims and 32.4% of male

victims of stalking are stalked by a current or former intimate partner.

7

Stalking victims report that stalking tactics most often include the perpetrator: following the

victim, approaching the victim or showing up in places, such as the victim’s home, work, or

school; using GPS technology or equipment to monitor or track the victim’s location; leaving

strange or potentially threatening items for the victim to find; sneaking into the victim’s home

or car and doing things to scare the victim by letting the victim know they had been there; using

technology such as a hidden camera, recorder, or computer software to spy on the victim from

a distance; making unwanted phone calls to the victim; sending the victim unwanted emails,

text or photo messages, or social media messages; and sending the victim cards, letters,

flowers, or presents when they knew the victim does not want.

8

Perpetrators who stalk victims do so repeatedly, and over a significant period of time: Twenty-

four percent of stalking victims said the stalking behavior lasted for two years or more, and

10.8% said it happened too many times to count.

9

In addition to the relentless nature of the crime, stalking is also a significant risk factor for

domestic violence-related homicide. In a study of cases of actual or attempted domestic

violence homicide involving a female victim who was physically assaulted by her violent partner

in the preceding year, nearly all (90%) of the victims were also stalked by their assailant.

10

Of

the women in that study who were murdered, 54% had reported the stalking to police before

they were killed. Another study assessing police records found that domestic violence cases

4

Morgan, R. E., & Truman, J. L. (2022). Stalking Victimization, 2019. U.S. Department of Justice Bureau of Justice Statistics.

Available at: https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/sv19.pdf.

5

Smith, Basile, & Kresnow (2022).

6

Morgan & Truman (2022).

7

Smith, Basile, & Kresnow (2022).

8

Smith, Basile, & Kresnow (2022).

9

Morgan & Truman (2022).

10

McFarlane, J., Campbell, J.C., Wilt, S., Sachs, C., Ulrich, Y., and Xu, X. (1999). Stalking and intimate partner femicide. Homicide

Studies, 3(4), 300–316.

3

with features of stalking or stalking charges were more threatening and violent than cases

without elements of stalking.

11

Young adults and people in the lowest income brackets experience higher rates of stalking:

people in households with incomes under $10,000 were more likely to be stalking victims than

people with household incomes over $10,000.

12

More than half of female stalking victims report that they were first stalked before age 25, and

about 1 in 4 were first stalked before age 18; those figures are similar for male victims of

stalking.

13

Research has found that stalking may be more common on college campuses than in

the general population.

14

According to one study of nearly 1,600 college students, 42.5% had

experienced some form of stalking victimization. However, victims may not recognize stalking

as a crime.

15

Of those students reporting behavior that qualified as stalking, only about one

quarter (24.7%) self-identified as stalking victims, and their likelihood of acknowledging the

behavior as stalking was linked with more severe and injurious actions by the offenders.

16

Being stalked, and suffering the fear and threats that characterize the crime, is significantly

correlated with the severity of symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and

psychological distress endured by female victims.

17

Stalking burdens victims with numerous

tangible and intangible costs, from emotional trauma to financial ruin. Anxiety, insomnia, and

depression, and other symptoms of traumatic stress are much higher among stalking victims

than people who have not been stalked.

18

Furthermore, stalking by a current or former

intimate partner has been found to escalate victims’ fear and distress, with victims being

significantly afraid that their stalkers would physically or sexually assault them, harass them and

their loved ones, threaten their children, cause financial problems, or humiliate them publicly.

19

In addition to the emotional and psychological toll of stalking, victims also face financial

hardship as they may have to move, cancel cell phone plans, change jobs, reduce employment,

or purchase expensive security systems in attempts to remain safe. One study found that

domestic violence victims who were stalked after obtaining a protection order incurred an

11

Klein, A. K., Salomon, A., Huntington, N., Dubois, J., & Lang, D. (2009). A statewide study of stalking and its criminal justice

response. (NCJ 228354). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice.

12

Morgan & Truman (2022).

13

Smith, Basile, & Kresnow (2022).

14

See, for example: Buhi, E. R., Clayton, H., & Surrency, H. (2009). Stalking victimization among college women and subsequent

help-seeking behaviors. Journal of American College Health, 57(4), 419–426.

15

McNamara, C. L., & Marsil, D. F. (2012). The prevalence of stalking among college students: The disparity between

researcher-and self-identified victimization. Journal of American College Health, 60(2), 168–174.

16

McNamara, C. L., & Marsil, D. F. (2012).

17

Fleming, K. N., Newton, T. L., Fernandez-Botran, R., Miller, J. J., & Burns, V. E. (2012). Intimate partner stalking victimization

and posttraumatic stress symptoms in post-abuse women. Violence Against Women, 18(12), 1368-1389.

18

Blaauw, E., Winkel, F. W., Arensman, E., Sheridan, L., & Freeve, A. (2002). The toll of stalking: The relationship between

features of stalking and psychopathology of victims. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 17(1), 50-63; and, Brewster, M. (2002).

Trauma symptoms of former intimate stalking victims. Women and Criminal Justice, 13(2/3), 141-161.

19

Logan, T. K., Walker, R., Hoyt, W., & Faragher, T. (2009). The Kentucky civil protective order study: A rural and urban multiple

perspective study of protective order violation consequences, responses, and costs. (NCJ 228 350). Washington, D.C.: U.S.

Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice. Available at: http://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/228350.pdf.

4

average of $610 in property damage or loss in a six-month period, compared to $135 for victims

whose abusers violated protection orders in ways that did not include stalking, and $15 for

those whose protection orders were not violated and who were not stalked.

20

Victims who

were stalked after the protection order was issued also lost more work time (78 hours) than

victims who did not experience further abuse or stalking while a protection order was in place

(4 hours).

21

Stalking is an underreported crime: around 30% of stalking victims in 2019 reported it to

police.

22

Victims’ reasons for not reporting include: a belief that the police cannot or will not do

anything, fear that they will not be believed, being afraid of the perpetrator, not wanting law

enforcement or courts involved in the matter, thinking that the perpetrator’s actions are not

serious enough to warrant reporting to police, and not having proof of stalking.

23

Furthermore,

research has documented that stalking is rarely identified in domestic violence cases that

include elements of stalking,

24

and people arrested for stalking often are not prosecuted.

25

OVW-Supported Training and Technical Assistance to Enforce Laws Related to Stalking and

Best Practices

To ensure the field has appropriate training, technical assistance, and access to best practice

information when addressing stalking, OVW has funded the Stalking Prevention Awareness and

Resource Center (SPARC). SPARC maintains a thorough and informative website with resources

for victim services providers, law enforcement officers, prosecutors, and corrections personnel.

SPARC identifies and derives its materials from best practices in each of these professions and

packages them in useful, engaging formats for the intended audience. The full spectrum of best

practices, tools, briefs, and more can be found at https://www.stalkingawareness.org/. Below is

a sampling of these resources organized by profession.

For victim services providers:

• SPARC provides these Quick Tips for stalking response strategies;

• A Guide for Advocates on responding to stalking, which is also available in Spanish; and

20

Logan, T. K., & Walker, R. (2010). Toward a deeper understanding of the harms caused by partner stalking. Violence and

Victims, 25(4), 440-455.

21

Logan & Walker (2010).

22

Morgan & Truman (2022).

23

Logan, T. K., Cole, J., Shannon, L., & Walker, R. (2006). Partner stalking: How women respond, cope, and survive. New York:

Springer Publishing Company; Tjaden, P. & Thoennes, N. (1998). Stalking in America: Findings from the national violence against

women survey. (NCJ 169 592). Washington, DC/Atlanta, GA: National Institute of Justice and the Centers for Disease Control

and Prevention; and Logan, T. K., Walker, R., Hoyt, W., & Faragher, T. (2009).

24

See, for example: Tjaden, P. & Thoennes, N. (2001). Stalking: Its role in serious domestic violence cases. Washington DC: U.S.

Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice; and Caperona, B. (2007). Domestic Violence in New Mexico, 2006 Highlights.

Albuquerque, NM: State of New Mexico, Department of Health, Office of Injury Prevention.

25

Klein, A. K., Salomon, A., Huntington, N., Dubois, J., & Lang, D. (2009).

5

• Addressing Stalking: A Checklist for Domestic and Sexual Violence Organizations, which

is also available in Spanish.

For law enforcement officers:

• SPARC provides this brief, informative tip sheet on recognizing stalking behaviors;

• This incident log provides a tool to assist officers in examining a pattern of stalking

behaviors; and

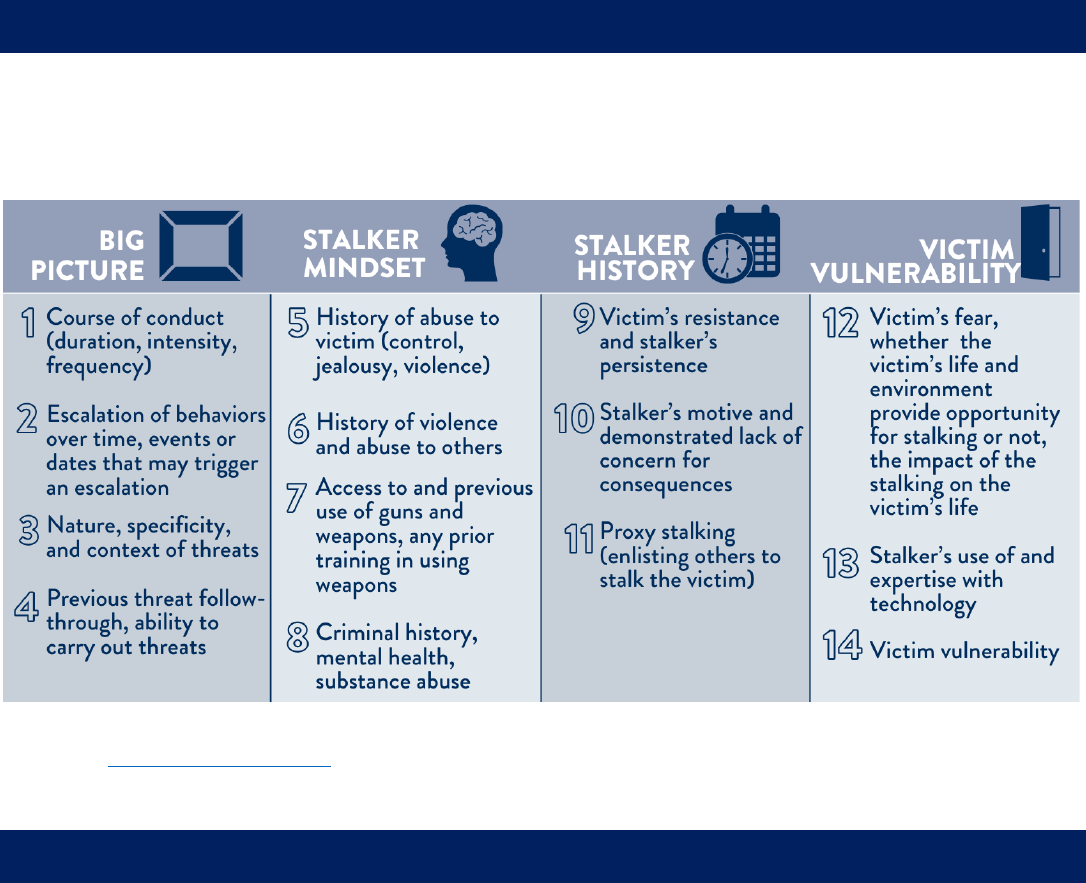

• The SPARC website links to the Stalking and Harassment Assessment and Risk Profile

(SHARP), a tool developed at the University of Kentucky that allows officers or victims to

enter key pieces of data about the stalking behavior and returns an assessment of risk

based on an empirically validated 14-factor model and a clear, concise narrative of the

case.

For prosecutors:

• SPARC publishes the Prosecutor’s Guide to Stalking, a guidebook for understanding the

crime of stalking, working with victims, presenting evidence, and more;

• SPARC directs prosecutors to webinars presented by SPARC’s parent organization,

Aequitas: The Prosecutor’s Resource on Violence Against Women. One such webinar is:

#GUILTY: Identifying, Preserving, and Presenting Digital Evidence; and

• SPARC presents custom training by request on a range of topics aimed at increasing the

rate of successful prosecution for stalking.

For corrections and probation personnel:

• SPARC publishes Responding to Stalking: A Guide for Community Corrections Officers to

educate officers on proper supervision of individuals convicted of stalking; and

• This checklist by SPARC as well as the SHARP tool can be used by corrections

professionals to document, assess, and understand stalking behaviors, whether in a

penal institution or by supervisees.

For college/university campus professionals:

• SPARC offers Quick Tips, a fact sheet, and an infographic tailored to campus

populations;

• Talking Stalking: Tips for Prevention/Awareness Educators;

6

• Tips for public awareness campaigns in campus communities; and

• Tips for campus stalking investigations and hearings.

For judicial officers:

• SPARC provides a Judicial Officers Bench Card on stalking; and

• A Judicial Officer’s Guide to stalking.

The materials listed above are compiled in this report, and additional resources and training

opportunities for professionals can be found at: https://www.stalkingawareness.org/.

STALKING RESPONSE STRATEGIES

FOR VICTIM SERVICE PROVIDERS

This project was supported by Grant No. 2017-TA-AX-K074 awarded by the Office on Violence Against Women, U.S. Department of Justice. The opinions,

findings, conclusions, and recommendations expressed in this publication/program/exhibition are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the

views of the Department of Justice, Office on Violence Against Women.

1000 Vermont Avenue NW, Suite 1010 | Washington, DC 20005 | (202) 558-0040 | stalkingawareness.org

@FollowUsLegally

DID YOU KNOW

Stalking is a dangerous crime that affects an estimated 13.5 million women and men each

year. Stalking — generally defined as a pattern of behavior directed at a specific person

that would cause a reasonable person to feel fear for their safety or the safety of others,

and/or suffer substantial emotional distress — is a crime under the laws of all 50 states,

the District of Columbia, the U.S. territories, and the federal government. Stalking can

have devastating and long-lasting physical, emotional, and psychological effects on

victims. The prevalence of anxiety, insomnia, social dysfunction, and severe depression is

much higher among stalking victims than in the general population. Victim advocates can

help victims devise a safety plan, navigate the criminal justice system, assert their rights

as crime victims, and obtain the services and support they need and to which they are

entitled.

HOW VICTIM ADVOCATES CAN HELP

1. Recognize that stalking is a pattern of behavior, and a stalking victim’s level of fear

and need for resources and assistance may vary and change based on the stalker’s

behaviors.

2. Realize that stalking victims may maintain contact with their offenders to keep

themselves (or loved ones) safe. Work with victims to establish safety plans.

3. Documentation can be extremely helpful in stalking cases. Victims could consider

using a documentation log.

4. Collaborate with others in your community, such as law enforcement, prosecutors,

and community corrections, to help protect victims of stalking. Health care providers

and members of faith communities also can be vital resources.

5. Work with law enforcement, prosecutors, and others to educate victims about the

ongoing dynamics of stalking cases and what evidence and documentation may be

required if they choose to report to the police.

While legal

definitions of

stalking vary from

one jurisdiction to

another, a good

working definition

of stalking is:

a pattern of

behavior directed at

a specific person

that would cause a

reasonable person

to feel fear for their

safety or the safety

of others, and/or

suffer substantial

emotional distress.

RESPONDING

TO STALKING

A GUIDE FOR ADVOCATES

This project was supported by Grant No. 2017-TA-AX-K074 awarded by the U.S. Department of Justice, Oce on Violence Against Women (OVW).

The opinions, ndings, conclusions, and recommendations expressed in this program are those of the authors and do not necessarily reect the views of OVW.

RESPONDING TO STALKING: A GUIDE FOR VICTIM ADVOCATES

TABLE OF CONTENTS

UNDERSTANDING STALKING

About the Crime of Stalking 4

The Intersection of Stalking with Other Crimes 7

The Impact of Stalking on Victims 9

THE ADVOCATE’S ROLE IN ASSISTING STALKING VICTIMS

Common Victim Reactions and Responses 12

Safety Planning 12

Protection Orders/Restraining Orders 16

Address Confidentiality Programs 17

Crime Victim Compensation 17

SCENARIOS

Case Scenarios 19-20

Conclusion 21

RESPONDING TO STALKING: A GUIDE FOR VICTIM ADVOCATES 3

UNDERSTANDING

STALKING

RESPONDING TO STALKING: A GUIDE FOR VICTIM ADVOCATES 4

ABOUT THE CRIME OF STALKING

INTRODUCTION

Stalking is a crime under the laws of all 50 states, the

District of Columbia, the U.S. Territories, Federal law,

and many tribal codes. An estimated 7.5 million

people in the United States are stalked every year;

yet the crime is seldom charged or prosecuted.

1

Stalking diers from

most crimes in two

important ways:

it involves repeat

victimization—it

is not a single

incident—and it is

defined in part by

the impact and toll it has on the victim. In fact, many

of the individual acts that make up stalking may be

legal by themselves and appear harmless to someone

unfamiliar with the case.

To complicate matters further, no single legal

definition exists: stalking varies widely in statute

definition, scope, crime classification, and associated

penalties.

How, then, can you support victims of the crime? To

recognize stalking and best help victims, advocates

and other professionals must be able to identify

stalking behaviors and help victims navigate the

criminal and civil justice systems, if victims are

choosing to access those systems for support.

DEFINING STALKING

In general, a good working denition of stalking is:

a course of conduct directed at a specic person

that would cause a reasonable person to feel fear.

Important components of this denition include:

• Course of conduct – a pattern of behavior involving

more than one action, committed over a period of

time (however short), that demonstrates a consistent

objective.

• Reasonable person – a legal standard of objectivity

used in place of subjective perceptions. It asks,

would another person in similar circumstances be

afraid because of the perpetrator’s behavior?

• Level of Fear – how fearful the stalking behaviors

make the victim. Criminal laws vary widely on what

level of fear a victim must experience to make the

stalker’s behavior criminal. Your state’s law may

require the victim to:

• Fear for their safety or experience substantial

emotional distress;

• Feel terrorized, frightened, intimidated, or

threatened, or fear that the perpetrator intends

to injure them or another person or damage

their property or another person’s property;

• Fear serious bodily injury or death.

1

Katrina Baum et al., “Stalking Victimization in the United States,”

(Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2009).

INDIVIDUAL ACTS

THAT MAKE UP

STALKING MAY BE

LEGAL AND

APPEAR HARMLESS.

Kim has been dating Tyson for 2 years. He calls her at work every day when she is eating lunch to see how

her day is going and prefers her to come straight home after work so they can spend time together. In the last

3 months, he has started getting upset if she doesn’t answer when he calls. Twice in the last week he drove to

the office to find out where she was. When she runs errands, he texts her multiple times each hour, wanting

to know exactly where she is. Kim didn’t mind at first, but it started to get worse after Tyson lost his job. He

started calling more frequently, leaving notes on her car while she was at work, and emailing her coworkers.

Kim has started leaving work a little early to make sure she is home when he says she should be. She tells you

she is afraid. He’s never physically hurt her, but his behavior is getting more unpredictable.

The course of conduct in this example is demonstrated by the perpetrator's repeated calls, visits to her office,

and insistence on knowing her location. Kim is shown to be a reasonable person because most people in her

circumstance would also experience fear. You are able to identify her level of fear because she tells you she is

afraid because he is unpredictable. She has also altered her behavior because she is afraid of what might

happen if she is late.

RESPONDING TO STALKING: A GUIDE FOR VICTIM ADVOCATES 5

UNDERSTANDING CONTEXT

AND FEAR

Compared to most other crimes, stalking is unique in

that the context of the stalking behavior is critical to

identifying and understanding what is occurring. The

victim plays a critical role in defining whether their

experience can be classified as stalking because the

perpetrator’s behaviors can only be identified as

stalking when the impact of those behaviors on the

victim is considered. Understanding a victim’s

response and level of fear may be difficult without

knowing the full context of the course of conduct and

any relationship that may exist between the victim and

the offender.

In some cases, the victim may not explicitly express

or display fear. The victim may be afraid or unwilling

to name the emotion, may believe that showing fear

will escalate the situation or provide satisfaction to

the stalker, or may wish to minimize the danger. Some

victims may struggle to admit feeling fearful as a

result of social norms regarding masculinity and

bravery. Advocates should provide access to the same

levels of support for all victims regardless of how

fearful they appear.

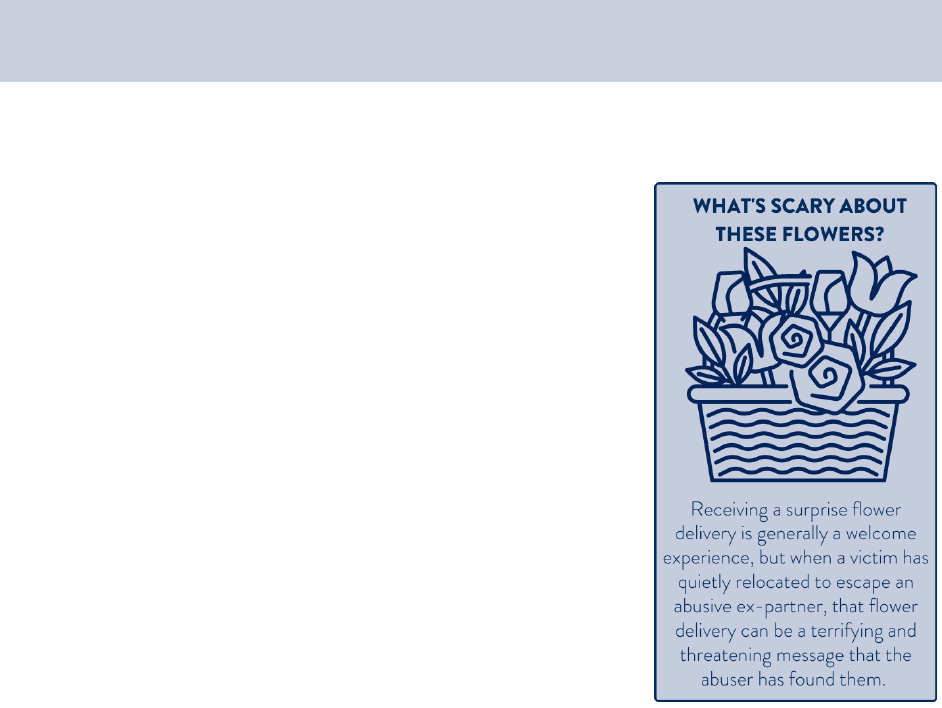

Often, perpetrators of stalking exploit a victim’s

specific fears or phobias and communicate

threats covertly in ways that seem harmless to

outsiders. For instance, perpetrators may send

the victim unwanted messages or gifts that

seem innocuous or even romantic—such as a

bouquet of roses. But the victim recalls the

perpetrator threatening that the day they

received roses would be the day they were

killed. Without this context, the victim’s terror

may seem irrational to a responder. Indeed,

perpetrators may provoke this reaction in part

to discredit the victim or cast doubt on the

victim’s mental health.

WORKING WITH UNDERSERVED

POPULATIONS

Victims of underserved populations often face

additional and unique barriers to the obstacles they

already face as stalking victims. Included in this

population of victims are children, people with

disabilities, older adults, lesbian, gay, bisexual,

transgender, and queer/questioning (LGBTQ)

identified individuals, American Indians and Alaska

Natives, victims with limited English proficiency,

immigrants, formerly incarcerated individuals, people

of color, individuals who are undocumented, and

others from historically marginalized communities. As

an advocate, it is essential that you consider the

context and the potential barriers a victim may face

when reporting the crime, seeking services, and

staying safe. These barriers may include language,

fear of law enforcement, accessibility, and care needs.

It is important to consider this for every victim,

because many disabilities or cultural needs may not be

readily apparent. While each situation may or may not

occur, you have the ability to enhance the safety of

victims by helping them prepare for any possible

situation. The best way to determine potential barriers

to safety is to ask victims if they would like to share

any concerns. Doing so will assist in safety planning

as well as the search for services.

ADVOCATES SHOULD

PROVIDE ACCESS TO THE

SAME LEVELS OF SUPPORT

FOR ALL VICTIMS REGARDLESS OF

HOW FEARFUL THEY APPEAR.

RESPONDING TO STALKING: A GUIDE FOR VICTIM ADVOCATES 6

STALKING BEHAVIORS

Perpetrators of stalking engage in many different

behaviors, and most use multiple tactics.

2

They

frequently invest time, energy, and money in

monitoring and pursuing their victims. Although

many stalking behaviors are not criminal as a single

occurrence, when viewed as a course of conduct that

causes the victim fear or distress, they add up to

stalking.

Common stalking behaviors include:

• Repeated phone calls, voicemails, emails, or text

messages

• Monitoring a victim’s phone activity or computer

use

• Sending unwanted gifts, letters, or cards

• Posting information or spreading rumors about the

victim on social media sites, in public places, or by

word of mouth

• Searching for information about the victim by

conducting public records or online searches, hiring

private investigators, digging through the victim’s

garbage, or contacting the victim’s friends, family,

neighbors, or co-workers

• Using technology, such as hidden cameras, to watch

the victim

• Driving by, waiting at, or showing up at the victim’s

home, school, or work

• Following the victim, either in person or via the use

of technology (e.g., GPS or location-based apps)

• Using a third party to contact or stalk the victim (i.e.,

proxy stalking)

• Committing identity theft or financial fraud against

the victim, such as opening, closing, or taking money

from accounts

• Using children to harass or monitor the victim

• Vandalizing or destroying a victim’s property, car, or

home

• Violating protective orders or other injunctions

• Threatening to hurt the victim or their family,

friends, or pets

• Threatening to kill the victim or others, self, or pets

These behaviors are not exhaustive and may change

or escalate over time. The average duration of stalking

is approximately two years, although intimate partner

stalking tends to last longer than non-intimate partner

stalking.

3

Advocates should check in regularly with

victims about the perpetrator’s stalking behaviors

as perpetrators of stalking often modify their tactics

based on the victim’s response. Also note that victims

commonly experience times of little stalking activity

and times of constant activity; a victim’s level of

engagement with the system may fluctuate

correspondingly.

STALKING THROUGH THE USE OF

TECHNOLOGY

Stalkers frequently use technologies, often legal

technologies, to stalk, monitor, and track their victims.

Comprehensive, up-to-date resources for advocates and

victims on how to best safety plan for stalking via

technology, can be found at the Safety Net team’s

website. Please see https://www.techsafety.org/ for more

information.

THREAT ASSESSMENT

Threat assessment is a process used to determine the

level of danger posed by a perpetrator to a victim at a

particular point in time. It is important to keep these

factors in mind when working with a victim. The most

dangerous perpetrators are those who:

• Engage in actual pursuit of the victim

• Possess or are interested in weapons

• Commit other crimes such as vandalism or arson

• Are prone to emotional outbursts and rage

• Have a history of violating protection orders,

substance abuse, mental illness and/or violence,

especially toward the victim

• Have made threats of murder or murder-suicide

The most dangerous times for a stalking victim are when:

• The victim has separated from the stalker

• The stalker has been arrested or served with a

protection order

• The stalker has a major negative life event, such as

the loss of a job or being evicted

• The stalking behaviors increase in frequency or

escalate in severity

2

Kris Mohandie et al., “The RECON Typology of Stalking: Reliability and

Validi- ty Based Upon a Large Sample of American Stalkers,” Journal of

Forensic Science 51, No. 1(2006).

3

P. Tjaden and N. Thoennes. “Stalking in America: Findings from the National

Violence Against Women Survey,” Research Report, Washington, DC: U.S.

De- partment of Justice, National Institute of Justice and Centers for Disease

Control and Prevention, 1998.

RESPONDING TO STALKING: A GUIDE FOR VICTIM ADVOCATES 7

THE INTERSECTION OF STALKING WITH

OTHER CRIMES

Stalking frequently co-occurs with other types of

victimization and criminal behavior. The stalking

course of conduct may include individually illegal acts

such as trespassing or property damage. Stalking

behavior may also be a precursor to other crimes, such

as sexual assault or homicide. Making the connection

between stalking and other associated crimes benefits

both the victim and the criminal justice system as a

whole. When criminal justice system personnel can

identify other crimes committed by the stalker, they

can more effectively establish the course of conduct

against the victim, take reports, gather critical

evidence, and file charges.

Some of the crimes that can intersect with stalking are

as follows:

INTIMATE PARTNER VIOLENCE

One study found that 81 percent of victims who were

stalked by a current or former intimate partner had

been physically assaulted by that partner.

4

A common

misconception is that stalking usually begins when a

victim of intimate partner violence leaves the

relationship. In fact, 57 percent of intimate partner

stalking victims report that the stalking behaviors

began before the relationship ended.

5

Checking the

victim’s phone logs, reading the victim’s emails,

confirming the victim’s whereabouts—these behaviors

may seem normal to the victim or less alarming than

any physical abuse. However, identifying these

behaviors as stalking is critical. Research is clear: when

physical abuse and stalking co-occur, the victim is at

greater risk of violence — including homicide

— and will need a comprehensive safety plan.

Perpetrators of intimate partner stalking are more

likely to physically approach the victim at their home

or place of work. They are also more likely to use a

third party, such as a family member or friend, to

further their stalking (for instance, asking a third party

to provide personal information about the victim, keep

track of where the victim is going, or communicate

messages to the victim). The combined elements of

stalking and physical violence require thoughtful and

detailed attention to additional risks.

HOMICIDE

Another study found that nearly 70 percent of

femicide victims were physically assaulted before

their murder. Of those, 90 percent had also

experienced at least one episode of stalking in the 12

months prior to their murder.

6

Perpetrators of

intimate partner stalking are better able to exploit the

victim’s physical and emotional vulnerabilities. They

are more likely to have had access to every part of the

victim’s life, including physical belongings (home,

vehicle), their daily routine (work, school), and

information about personal affairs (finances, medical

history).

SEXUAL ASSAULT

Stalking intersects with sexual assault in several

ways. A stalker may threaten to sexually assault the

victim, attempt to get someone else to sexually assault

the victim, or carry out a sexual assault against the

victim. Research shows that 2 percent of people who

are stalked were also sexually assaulted by the

perpetrator, and 31 percent of women who are stalked

by an intimate partner were also sexually assaulted by

that partner.

7, 8

4

Patricia Tjaden and Nancy Thoennes, “Stalking in America: Findings from

the National Violence Against Women Survey,” National Institute for Justice

Centers for Disease Control Research in Brief (1998).

5

Patricia Tjaden and Nancy Thoennes, “Stalking in America: Findings from

the National Violence Against Women Survey,” National Institute for Justice

Centers for Disease Control Research in Brief (1998).

6

McFarlane et al., “Stalking and Intimate Partner Femicide,” Homicide

Studies 3, No. 4 (1999).

7

Katrina Baum et al., “Stalking Victimization in the United States,”

(Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2009).

8

Patricia Tjaden and Nancy Thoennes, “Stalking in America: Findings from

the National Violence Against Women Survey,” National Institute for Justice

Centers for Disease Control Research in Brief (1998).

RESPONDING TO STALKING: A GUIDE FOR VICTIM ADVOCATES 8

Prior to committing sexual assault, perpetrators may

engage in a variety of stalking behaviors, including

following the victim, repeatedly contacting the victim,

learning the victim’s habits and daily routines, and

gathering personal information about the victim.

These behaviors may be an attempt to identify

potential vulnerabilities or to groom the victim.

After committing or attempting to commit a sexual

assault, the perpetrator may repeatedly contact the

victim in order to:

• Threaten or manipulate them into not reporting

the incident

• Determine what the victim recalls, if drugs or

alcohol were involved

• Frame the incident as consensual

• Maintain social contact

Advocates can help victims of sexual assault identify

stalking behaviors and emphasize how reporting

stalking behaviors may help law enforcement ocers

and prosecutors investigate and successfully prosecute

the crime.

PROPERTY DAMAGE

Another crime that is frequently part of the stalking

pattern of behavior is property damage. Advocates

can assist victims by encouraging them to be aware of

the connection between stalking behaviors and recent

property crimes they have experienced. Although

criminal mischief and vandalism, such as broken

mailboxes or damaged tires may seem commonplace,

they can also be part of a stalking course of conduct.

While broken windshields on every car parked on

a residential street may simply indicate common or

random vandalism, damage that is either specic

to the victim’s belongings or repeated should be

evaluated for stalking involvement.

OTHER CRIMES

Advocates can assist victims by discussing the benets

of explaining to law enforcement the entire context of

the stalking behavior if the victim decides to report

associated crimes. Some of the crimes that may be part

of the stalking course of conduct include:

MAKING THE CONNECTION

Establishing a connection between stalking and

other crimes serves a number of important purposes,

including:

• Supporting the victim’s emotional recovery

• Minimizing the victim’s self-blame

• Demonstrating intentional contact on the part of

the stalker

• Helping law enforcement and prosecutors

understand how other crimes fit into the larger,

targeted course of conduct

• Strengthening the overall criminal justice system

response to stalking

• Nonconsensual

Dissemination of

Intimate Images*

• Protective Order

Violations

• Robbery

• Sexual Assault

• Theft

• Threats

• Trespass

• Utility Theft

• Vandalism

• Vehicle Tampering

• Vehicle Theft

• Voyeurism

• Wiretapping

• Assault

• Burglary

• Child Abuse

• Conspiracy

• Criminal Mischief

• Eavesdropping

• Forgery

• Fraud

• Harassment

• Hate Crimes

• Home Invasion

• Homicide

• Identity Theft

•

Intimate Partner Violence

• Kidnapping

• Mail Theft

*Definition: The Nonconsensual Dissemination of

Intimate Images is the sharing of individuals’

nude photos and videos without their consent.

This may happen on social media or other

websites. While the photos may have been taken

with permission of the victim, perpetrators of

stalking may

use the threat of distribution to

intimidate the victim.

RESPONDING TO STALKING: A GUIDE FOR VICTIM ADVOCATES 9

THE IMPACT OF STALKING ON VICTIMS

Stalking victimization can permeate every aspect of a

victim’s life. Victims of stalking experience many of

the same effects as victims of other crimes, such as

substance abuse, anxiety, and social isolation.

However, victims of stalking also face unique

challenges. Stalking behavior is often persistent and

unpredictable, and can take place over a long period

of time causing repeated trauma. Stalking can affect a

victim’s physical and emotional health, their family

and friends, financial stability, and their job.

IMPACT ON PHYSICAL AND

MENTAL HEALTH

The emotional and physical effects of stalking can

manifest in a variety of ways. The impact of stalking

on the mental and physical health of victims affects

both their ability to safety plan while the stalking is

ongoing as well as their ability to recover after it has

ended. Stalking victims have a higher prevalence of

anxiety, insomnia, social dysfunction, and severe

depression than the general population, especially if

the course of conduct includes being followed or the

destruction of property. Advocates must discuss how

to manage these effects with victims.

Victims may experience a variety of somatic

symptoms, including headaches, general aches and

pains, feelings of weakness or numbness, sleeping

too much or too little, nightmares and persistent

dreaming, and changes in weight. Increased anxiety,

common among stalking victims, is also connected to

physical symptoms, including shaking, chest pains,

and panic attacks. The physical manifestations of

stress extend to a lowered immune system response

and influence current or underlying medical

conditions. Support from a medical professional,

such as a therapist or general practitioner, may help

the victim to cope with the physical and mental

effects they are experiencing.

9

9

Eric Blauuw et al. “The Toll of Stalking,” Journal of Interpersonal

Violence 17, no. 1(2002).

IMPACT ON PERSONAL

RELATIONSHIPS

Stalking aects not only victims, but also their family,

friends, and coworkers. Some stalking perpetrators

may attempt to contact the victim’s family members or

friends for information, such as the victim’s location,

workplace, or contact information.

Other perpetrators may ask third parties to contact

or follow the victim for them. This practice is called

proxy stalking. Perpetrators of intimate partner

stalking may also attempt to use children to stalk.

Because many proxy stalkers are part of the victims’

support network, victims may nd it challenging

to reach out for support. Victims may be reluctant

or not want to involve people they know out of

embarrassment or shame. They may fear the

perpetrator will act out against the third party if they

attempt to ask for help. In addition, they may be

unsure about the safety of the technology they use to

communicate with their support network. Advocates

must encourage stalking victims to think broadly

about whom they trust and how to safely

communicate with their support system about their

situation.

• Abuse of drugs or alcohol

•

Inability to study

•

Anger

•

Irritability

•

Anxiety

•

Loss of confidence

•

Confusion

•

Loss of relationships

•

Depression

•

Minimization

•

Economic losses

•

Nightmares

•

Embarrassment

•

PTSD

•

Emotional numbness

•

Self-blame

• Fatigue

• Sexual dysfunction

• Fear

• Shame

• Flashbacks

• Shock

• Frustration

• Sleep disturbances

• Social isolation

• Guilt

• Suicidal ideation

• Hypervigilance

• Inability to accomplish

daily tasks

• Inability to concentrate

• Weight changes

COMMON EFFECTS OF STALKING

RESPONDING TO STALKING: A GUIDE FOR VICTIM ADVOCATES 10

IMPACT ON FINANCES

Stalking often results in direct and indirect economic

losses for the victim that occur in a variety of ways.

• Property damage – cost of replacement or repairs

for damage caused by the perpetrator

• Legal processes – court fees, attorney fees, costs to

travel to court appointments, and child care for

times when caregivers are in court

• Medical bills (mental and physical health) – stalking

victims will utilize health services at a higher rate

than victims of domestic violence alone

10

• Technology – cost to replace technology that may

have been compromised by the stalker

• Relocation – if the victim chooses to move to get

away from the perpetrator

• Lost wages

Advocates should be prepared to discuss options for

nancial assistance that support the victim’s safety. See

Crime Victim Compensation on page 17.

IMPACT ON THE WORKPLACE

Stalking can affect victims’ work in a variety of ways.

Victims of stalking may take time off to go to court,

meet with an advocate, or take care of their mental or

physical health, resulting in lost wages if they do not

have paid leave.

11

Many victims do not report their stalking

victimization to their employer, or may only report to

trusted coworkers rather than managers or the human

resources department. The victim’s supervisor may

not understand the victim’s behavior (e.g., distracted

or declining performance) and may wrongfully

conclude that the victim is a poor employee, resulting

in discipline or termination. In some cases, employers

who know an employee is being stalked may be

concerned about a risk to the workplace and ask the

victim to resign.

As an advocate, your role is to help victims identify

and weigh the pros and cons of discussing the stalking

with their employer and to help them contact an

attorney if they are wrongfully terminated. Victims of

stalking may have protections, and advocates can

assist by learning more about available options at

http://workplacesrespond.org.

10

Logan, T., Walker, R., Hoyt, W. and Faragher, T. “The Kentucky Civil

Protective Order Study: A Rural and Urban Multiple Perspective Study of

Protective Order Violation Consequences, Responses, and Costs.” 2009.

Washington, DC: National Institute of Justice, U.S. Department of Justice.

11

Many states now have laws to protect victims of domestic violence and

stalking by mandating employers oer paid sick leave for victims to attend

court hearings. Yet, in some states, the stalking may aect their job security.

RESPONDING TO STALKING: A GUIDE FOR VICTIM ADVOCATES 11

THE ADVOCATE

ROLE IN

ASSISTING

STALKING

VICTIMS

RESPONDING TO STALKING: A GUIDE FOR VICTIM ADVOCATES 12

COMMON VICTIM REACTIONS AND

RESPONSES

Reactions to stalking are as diverse as victims

themselves. As a group, however, victims share

several common responses:

• Minimizing: Victims may minimize individual

stalking behaviors and the risk the offender poses.

They may isolate events—focusing on a recent, less

serious behavior instead of connecting it to more

serious violations in the past. For example:

• “They’re only text messages.”

• “He would never really harm me.”

• Avoiding family or friends: Victims may avoid

family and friends because they feel embarrassed,

ashamed, or responsible for what is happening. In

many instances, the stalker is someone known to the

victim, their family, and their friends. They may

avoid contact with loved ones in order to also avoid

the perpetrator. They may be afraid they won’t be

believed or that their friends and family will take

sides against them. Victims may also want to keep

loved ones safe from the stalker.

• Negotiating for safety: Victims may negotiate with

the perpetrator for their own or others’ safety. They

may agree to demands the perpetrator makes or

maintain contact in an effort to prevent additional

harm.

• Taking steps to improve their personal security:

Many victims engage in informal safety planning on

their own to cope with the perpetrator’s tactics and

behaviors. For example, they may take a different

route to school or work, temporarily stay with a

friend, or change the locks on their door.

As an advocate, it is important to recognize and

validate any steps victims have taken to stay safe, oer

guidance on additional measures they could take, and

support their actions moving forward.

SAFETY PLANNING

Advocates can help victims strategize about how to

more safely respond to stalking by creating a safety

plan. A safety plan is a combination of suggestions,

concrete steps, and strategic responses designed to

increase the victim’s safety during specific

situations. Every victim’s safety plan is different—

tailored to their unique circumstances—and every

perpetrator will respond differently to those safety

tactics. It is

important to keep in mind—and

communicate to the victim—that safety plans do not

guarantee a victim’s safety, but they can greatly

increase it.

Effective safety plans are:

• Flexible – Many options are available for any given

scenario. Victims are able to evaluate which option

best fits their current situation. The plan can also be

adjusted if the perpetrator’s behavior changes.

• Comprehensive – The safety plan considers every

aspect of the victim’s life, including family and

friends, children, school, work, and daily routine.

• Contextual – The plan should account both for what

the victim is currently experiencing and for the

pattern of previous behavior.

To help craft an effective safety plan, advocates can:

• Listen and ask questions non-judgmentally

• Help identify the victim’s specific needs and goals

• Discuss and analyze risks

• Explore strategies and resources

• Provide information and options

RESPONDING TO STALKING: A GUIDE FOR VICTIM ADVOCATES 13

SAFETY-PLANNING SUGGESTIONS

Below are suggestions for safety planning, including if

a victim is currently in a relationship with the

perpetrator, has recently ended the relationship,

has never had an intimate relationship with the

perpetrator. Advocates should also consider if the

victim is seeking services for the first time. Remember

to evaluate each component with regard to (A) the

context of the situation and (B) how the perpetrator

will likely respond, according to the victim.

DISENGAGEMENT

In many cases, it is best for stalking victims to

completely disengage with the perpetrator to stay

safe. For some perpetrators of stalking, any contact

may reinforce their behavior, even if the interaction is

negative. It may be best for a victim to let every call

from a perpetrator go to voicemail rather than to

answer and ask the perpetrator to stop calling. The

perpetrator may see this contact as evidence their

methods have been successful, rather than a rejection.

Additional advocacy and safety planning may be

required to address the following circumstances:

• Children – If the victim and perpetrator share

custody of any children, the victim is unlikely to be

able to completely disengage.

• Safety – For some victims it may be safer to remain

in contact. A victim may answer a phone call from

the perpetrator to ward off an escalation in behavior,

such as the perpetrator showing up at the victim’s

house.

• Small communities – In rural areas or closed

communities (such as college or university

campuses, military property, or tribal lands), it may

be impossible to avoid seeing the perpetrator.

DOCUMENTATION

Victims should be encouraged to document all

stalking behaviors and preserve any evidence such as

emails, text messages, or gifts – even if they do not

intend to move forward with criminal charges. If the

victim decides to report the stalking to law

enforcement or apply for a protective order, this

documentation is an important component of

demonstrating the course of conduct. It also provides

victims, service providers, and law enforcement

officers with an overview of the stalking behaviors

and timeline so they can identify any escalation in

behaviors. A sample stalking log is included here:

www.stalkingawareness.org/documentation-log/

To stay safe while documenting behaviors, victims

need to consider:

• Computer documentation – Is the computer safe

from spyware that could give the perpetrator access

to all of the documents, websites, emails, and other

information the victim is using?

• Paper documentation – Can several copies be stored

in different places that the perpetrator cannot

access? These locations could be a friend or family

member’s house, the victim’s workplace, a sports

locker, or a safety deposit box.

Emma is sitting in your office with her two children, Noah and Mason. Lucas, her ex-boyfriend and the

father of her children, threatened to hurt her children last month if she did not move back in with him.

Since then, he has been repeatedly texting and calling her cellphone and showing up unexpectedly at her

children’s daycare. Before they separated, he monitored her location using her cell phone. Emma wants to

know what she can do to be safe.

FLEXIBLE – It is important that Emma and her children have somewhere safe to stay. She can stay in her

home if she feels safe there. But it’s also important to have a backup plan. Can they stay with a relative or

a friend for a few nights with little notice? Can Noah and Mason attend a different daycare or stay with a

relative or friend for a few days? Is there a local shelter where they can stay? Do they have enough money

to stay in a hotel?

COMPREHENSIVE – Can she alter her work schedule so that Noah and Mason go to daycare at a

different time? Is she comfortable talking to the daycare teachers about what is happening? Do Emma

and Lucas have a parenting plan in place? Has she discussed the situation with her employer?

CONTEXTUAL – Lucas appears to use technology as a way to track Emma. The best way to determine

potential barriers to safety is to ask victims if they would like to share any concerns. Doing so will assist

in safety planning as well as the search for services. Can she talk to her employer about security

protection for her computer?

RESPONDING TO STALKING: A GUIDE FOR VICTIM ADVOCATES 14

Documentation should include:

• Time of incident

• Location of incident

• Full names of any witnesses

• Incident number if a police report was taken

• Detailed description of what happened

Some victims may be reluctant to document the

stalking behaviors. They may feel unsafe or find the

process upsetting. Be sure to discuss with victims the

fact that any documentation or evidence they provide

to law enforcement could be introduced as evidence

in court or inadvertently shared with the perpetrator.

Victims should not include any information that they

do not want the perpetrator to access.

EVIDENCE

Examples of evidence that should be documented and

maintained include:

•

Letters or notes written by the perpetrator to the

victim

•

Objects sent to or left for the victim, including “gifts”

•

Voicemail messages left by the perpetrator

•

Evidence of phone tapping or tampering

•

Emails, preserved electronically and printed out with

an expanded header showing the IP address

•

Telephone records

•

Text records

•

Screen shots of social network posts to or about

the

victim

•

Screen shots of other online posts to or about the

victim, including the website address (also known as

a “URL”)

•

Photos or videos

posted online of or about the victim

(download a copy and document any active URLs)

SUPPORT SYSTEM

For most stalking victims, having a few people they

can trust and rely on is essential to their ability to

cope and recover from the crime. Advocates can help

victims think broadly about who in their network can

provide that support. Some victims may want to

consider implementing a daily safety check with a

member of their support system. This can be as simple

as a text message every day letting the person know

they are okay. This support person may be someone

well-known to the victim, a casual acquaintance, or

professionally connected, including:

• Family members, such as siblings, cousins, aunts,

and uncles

• Friends

• Neighbors

• Members of their house of worship

• Members of other affiliated, community, or

professional groups

• Coworkers

• Medical or legal professionals

• Advocates

For some victims this exercise may be challenging.

They may wish to keep people safe by not involving

them or they may be reluctant to trust anyone,

especially if the perpetrator knows all of their friends

and family.

REPORTING TO POLICE

Advocates can help victims think about whether they

want to report stalking to law enforcement and how

to stay safe if they choose to report. While reporting

to law enforcement often seems like an obvious step,

it may not be safe for a victim to report the crime at

the time of the incident. Instead, they may choose to

file

a report on a later, safer date. Sometimes,

reporting stalking can cause the perpetrator to

escalate the behavior, creating an increased level of

danger for the victim.

If a victim decides to report to the police, advocates

can support their decision by helping them

understand what to expect. Victims can prepare by:

• Expecting law enforcement officers to ask specific

and intimate questions such as “Does the stalking

cause you to feel fear?”

• Identifying incidents that demonstrate the course of

conduct

• Outlining the events to ensure clear communication

• Bringing any related documentation of the stalking,

such as the stalking incident log

• Understanding that law enforcement may or may

not arrest the perpetrator

• Remembering investigations can take a long time

RESPONDING TO STALKING: A GUIDE FOR VICTIM ADVOCATES 15

SAFETY PLANNNG TIPS

1. Think about all of the people potentially affected:

children, grandparents, pets, coworkers, etc.

2. Keep in mind both short-term and long-term safety:

a. Short-term safety can be a few weeks to a few

months, depending on the situation and the

persistence of the perpetrator.

b.

Long-term safety planning may not be

necessary for every victim but is important to

discuss, as stalking behavior continues for an

average of two years.

3. Provide resources for the victim to access at any

time, such as a 24-hour hotline.

a. Check for local resources first.

b. If there are no local 24-hour hotlines in

your area:

i. National Domestic Violence Hotline:

1-800-799-7233 or chat online here

https://www.thehotline.org.

ii. National Sexual Assault Hotline (RAINN):

1-

800-656-4673 or chat online here

https://hotline.rainn.org/online.

c. VictimConnect Resource Center can assist with

safety planning and resources for victims of

stalking:

1-855-484-2846 or chat online here

https://chat.victimsofcrime.org/victim-connect/.

SAFETY BY LOCATION

IN THE HOME:

• Avoid bathrooms, the kitchen, the garage and other

areas where weapons may be found when the

perpetrator is in the home.

• Identify which rooms have strong doors, locks, and

windows that open.

• Install an alarm system and/or motion detector;

some security companies will provide these for free

or a discounted rate to victims of stalking.

• Talk to neighbors: ask them to call 911 if they see

the perpetrator or hear something concerning; if

comfortable sharing, give them copies of protective

orders.

AT WORK:

• Change telephone numbers, location, and hours if

possible.

• Provide copies of protective orders to supervisors.

• Park close to the office door or ask someone to walk

them to their car.

• Develop an office or work-escape plan.

• Talk with security guards and receptionists about

who is allowed to visit; provide a photograph of the

perpetrator; ask front-desk personnel to call before

letting someone into their office.

WITH CHILDREN

If the victim has children, they may be affected by

the stalking, regardless of their relationship to the

perpetrator. Victims of stalking with children

should consider the following:

• Identifying safe places for the children to hide if the

perpetrator approaches them or the victim.

• Teaching the children how to call 911, and giving

them permission to do so.

• Discussing who the children can go to for help

(e.g., family members, neighbors, law enforcement).

• Providing copies of protective orders to schools,

daycares, and other care providers.

• Making sure every person who takes custody of the

children knows who else is allowed to pick them up.

• Obtain advice about civil legal remedies to protect the

children.

RESPONDING TO STALKING: A GUIDE FOR VICTIM ADVOCATES 16

PROTECTION ORDERS/

RESTRAINING ORDERS

A protective order is a legal order issued by a state court

that requires one person to stop harming and/or

contacting another. Each state may have several types of

protective orders—such as civil protective orders,

criminal protective orders, or restraining orders—

and they may have different names. (For example,

Pennsylvania has “protection from abuse” orders).

Some protective orders are specific to domestic and

intrafamilial violence, while others are broader, covering

stalking, harassment, sexual assault, and other types of

abuse. Civil protection orders do not require that the

perpetrator be charged or convicted; as long as the

behavior, the relationship between the parties, and the

harm or threat to the victim come within the legal

requirements, the court can issue an order. Violations of

the civil protection order are typically criminal offenses.

A protection order is one possible tool a victim can

use to help stop the stalking and enhance their safety.

However, they are not effective in every case and may in

fact escalate the stalking behavior in some cases.

To help victims of stalking understand the risks and

benefits of seeking a protection order, consider the

following:

• How do they anticipate the perpetrator will respond

to the protection order?

•

•

How and when will the perpetrator be served with

the protection order?

Will it be dangerous for the victim to appear in

court because the perpetrator will know where the

victim is?

• How will the process aect any current or future

family law proceedings?

• Will the victim call law enforcement if the

perpetrator violates the order?

For a protection order to be most eective, victims

should also know:

• Enforcement may be easiest if they carry a copy of the

protection order with them wherever they go.

• They should provide copies of the order to

employers, schools, babysitters, landlords, neighbors,

family members, and others, especially if the order

prohibits the perpetrator from being at certain

locations or contacting children.

• Orders of protection must be honored in other

jurisdictions. For more information, see The National

Center on Protection Orders and Full Faith and

Credit, a program of the Battered Women’s Justice

Project.

http://www.bwjp.org/our-work/projects/protection-

orders.html

• Violations of a civil protection order may permit or

require the police to make an arrest if they find

probable cause to believe the offender has violated

the order.

• An attorney who represents the perpetrator may ask

the victim to agree to mutual orders in an effort to

discredit the victim. This means that both parties

would have a protection order against the other. The

victim does not have to do this in order to obtain an

order that prohibits the stalking offender from

continued stalking. Victims should seek legal counsel

before agreeing to such mutual order. The existence

of such an order may allow for the perpetrator to file

criminal charges against the victim.

Advocates have an important role in helping victims

weigh the dierent benets and drawbacks regarding

protection orders as well as guiding them through the

court system and ling process.

RESPONDING TO STALKING: A GUIDE FOR VICTIM ADVOCATES 17

ADDRESS CONFIDENTIALITY PROGRAMS

Address Confidentiality Programs (ACPs) allow

victims of stalking, sexual assault, domestic violence,

or other types of crime to receive mail at a substitute

address. ACPs keep the victim’s actual address

private and prevent oenders from locating the

victim through public records. Mail is sent to the

legal substitute address, often a post

office box, and

then forwarded to the victim’s actual address. The

substitute address can be provided whenever the

victim’s address is required by a public agency. While

Address Condentiality Programs can assist with

a victim’s safety, they do not guarantee their safety.

Victims can increase their safety by:

• Limiting the number of people they tell about

their address, doing their best to ensure that these

individuals are trustworthy and discreet.

• Abiding by the terms of the ACP. Some ACPs will

remove a participant from the program if they

violate the terms.

• Advocates can help victims understand the terms of

the program in their particular state and how it

operates. However, not every state has an Address

Confidentiality Program. If your state does not have

a program, it is essential that you discuss other ways

for victims to make it more difficult for the offender

to locate them.

CRIME VICTIM COMPENSATION

One possibility for financial assistance is Crime

Victim Compensation. Every state has a state-level

Crime Victim Compensation program. Victims of

stalking who apply to crime victim compensation

may be eligible to have some of their crime-related

expenses reimbursed, such as lost wages, medical

bills and mental health counseling, and lock changes.

Some states may assist with relocation expenses for

safety.

Each program, however, has different requirements

and benefits. Most states require a police report, but

some will also accept a protection order, a SANE

exam (rape kit), or a neglect petition (for victims of

child abuse and neglect). For more information on

the program in your state, visit the National

Association of Crime Victim Compensation Boards.

http://www.nacvcb.org/

Advocates can help victims of stalking navigate this

process by understanding the documents, deadlines,

and reimbursable expenses for their state’s program.

RESPONDING TO STALKING: A GUIDE FOR VICTIM ADVOCATES 18

PRACTICE

RESPONDING TO STALKING: A GUIDE FOR VICTIM ADVOCATES 19

CASE SCENARIOS

For each case scenario, think about the following questions and how you would support this victim

with the resources in your community:

• Which risk factors are present?

• Does the perpetrator pose a threat?

• If so, to whom?

• In your professional capacity, how would you work with the victim at this point?

• What questions would you like to ask the victim? What information would be helpful?

• What safety concerns do you have and how can they be addressed?

• What options and resources would you provide to the victim?

• Would collaborating with other agencies or organizations to support this victim be useful?

1. DEREK AND JAMES

Derek comes to you to discuss a confrontation with his

ex- boyfriend, James, whom he dated for about 5

months. They broke up last month, but the break-up

didn’t go well.

This morning when Derek left his apartment, James

was parked in front of the building. James approached

him and started yelling, saying he was still in love

with Derek and knows he is still in love with him.

James told Derek it didn’t matter if he tried to ignore

him, he would always be there to show him how

much he cares. James left when a neighbor came out to

see if Derek was okay.

Derek goes on to tell you that things were okay the

first few months of their relationship, but then James

started demanding more of his time. James wanted the

two of them to spend all of their free time together and

would get upset when Derek wanted to spend time

with his friends or family. James would talk about

spending the rest of their lives together, even though

Derek made it clear that he wasn’t looking to settle

down at this point in his life. He tried talking to James

several times about keeping it casual and James would

back off for a few weeks before reverting to his

insistence on a permanent relationship. Derek then

decided that he and James clearly wanted different

things from the relationship and broke up with him.

Since they broke up, James keeps trying to stay in

touch with Derek. Derek gets 15-20 texts and emails

from James every day. James kept messaging him

while he was at work until he blocked him. James

then sent him an angry, threatening email. James

keeps showing up at the same places Derek is. At first

Derek thought this was just a coincidence, but now

he’s not so sure.

Consider:

A.

James keeps showing up at the same locations

as Derek; he may be tracking him through

spyware on his cell phone.

B.

A protection order may be a good option for

Derek, but it may also cause the behavior to

escalate. It is important to examine the pros

and cons of

filing for one.

C.

Derek’s neighbor has demonstrated she cares

about his well-being. Derek could ask her to

call the police if she sees James outside the

apartment again.

RESPONDING TO STALKING: A GUIDE FOR VICTIM ADVOCATES 20

2. JANET

Janet calls your hotline regarding items that have gone

missing from her apartment. She tells you that she is

70 years old and lives alone. Over the last few months,

objects in her apartment have disappeared or have

been moved to a different location in the apartment.

She describes the items as being of little value to her,

items such as a notepad or a houseplant.

She has called law enforcement several times to report

the missing items, but they don’t seem to believe her.

They have come to the apartment three times, but the

last time they didn’t take a report. Law enforcement

told Janet that there was no sign of forced entry.

Janet has told her adult children about the problem

and they have started talking about moving her to an

assisted living facility. She doesn’t want to live in a

facility so she has stopped telling her children when it

happens.

Consider:

A. The law enforcement officers who spoke with

Janet seem to have perceiv ed Janet as confused

and forgetful. When you talk to her, she doesn’t

sound confused, just scared.

B.

You remember a similar case from a few years

ago. Using

a hidden camera, a detective caught a

man using a key to get into an older victim’s

home and move her things.

C. Janet is feeling alone, her safety plan should

include reaching out to her family. As a family,

they could meet

with an advocate to discuss her

possible options.

3. MACKENZIE AND DAVID

Mackenzie is being stalked by her neighbor whom she

has known most of her life. They live on nearby tribal

lands. David started texting her repeatedly several

months ago, asking her to go on a date with him.

Mackenzie tells you that she had a boyfriend at

the time which she told David. He kept texting her

anyway. When Mackenzie and her boyfriend broke

up, David started calling her. Mackenzie told him she

wasn’t interested in dating him, but he continued to

call her. Last week, he started showing up at her work

around lunch time, asking her to go to lunch with

him. She also started getting texts and phone calls

from members of David’s family pressuring her to

date him. Mackenzie tells you that she thinks his

friends and family are helping him keep track of her.

It’s the type of town where everyone knows everyone.

Last night, David was sitting on her front porch when

she got home and wouldn’t leave. Mackenzie didn’t

feel safe opening her door when he was there so she

left and spent the night at her parents’ house. She is

considering moving so that she no longer lives next

door to him.

Consider:

A. Help Mackenzie think through her support

network Is there someplace she can stay that is

safe? Who can she trust?

B. Does she think a protection order would be

effective or would he ignore it? If she thinks he

would listen to it, it may also protect her from

his family as the order could bar 3rd party

contact.

C. If Mackenzie decides to move, she could apply

to participate in an address confidentiality

program depending on her state.

4. MARCUS

Marcus is a college professor at a small liberal arts

university in the same city where your program is

based. One of his students, Katie, has been visiting his

office hours a lot lately. She didn’t do very well on the

last exam and she was visibly upset about it when he

returned the tests to the class last month.

She emails him multiple times a day and has started

showing up at his favorite morning coffee shop several

times a week. Yesterday, she told him that if she didn’t

do better on the next test, he would be sorry.

Consider:

A. Marcus works for a university which means an

issue with a student could have repercussions

on his career. If Marcus is comfortable talking

with his supervisor about this, it may help him

protect his job.

B. Marcus has a fairly regular routine. He can

change it up by going to a different coffee

shop and working in a different office or at the

library.

RESPONDING TO STALKING: A GUIDE FOR VICTIM ADVOCATES 21

CONCLUSION

Stalking happens much more frequently than most

people realize and is often connected to many other

crimes. It is vital that victim advocates are able to

identify stalking behaviors and build eective safety

plans with victims of stalking. We hope this guide

will help you identify stalking behaviors, the barriers

stalking victims face, and solutions that enhance

their safety. Please visit our website for additional

information.

The Oce on Violence Against Women supported the

development of this product under award 2017-TA-

AX-K074. The opinions and views expressed in

this document are those of the authors and do not