© 2020 Mangum Economics

JANUARY 2020

THE IMPACT OF DATA CENTERS ON THE STATE

AND LOCAL ECONOMIES OF VIRGINIA

PREPARED BY

LEAD SPONSORS

SUPPORTING SPONSORS

NVTC 2020 Data Center Report

Table of Contents

About the Northern Virginia Technology Council ..................................................................................... 1

Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................. 1

Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................. 2

Introduction to Data Centers in Virginia ................................................................................................... 4

Economic Profile of Data Centers in Virginia ........................................................................................ 5

The Northern Virginia Data Center Market in 2019 .......................................................................... 5

The Regional Distribution of Data Centers in Virginia ....................................................................... 7

The Upward Trend in Virginia’s Data Center Industry ....................................................................... 8

The High-Performance Data Center Industry in Virginia ................................................................... 9

The Impact of Data Centers on Virginia State and Local Economies.......................................................... 9

Virginia Statewide.............................................................................................................................. 11

Central Virginia .................................................................................................................................. 12

Hampton Roads ................................................................................................................................. 13

Northern Virginia ............................................................................................................................... 14

The Northern Virginia Community College Programs ..................................................................... 14

Southern Virginia ............................................................................................................................... 15

Southwestern Virginia ....................................................................................................................... 16

Valley ................................................................................................................................................ 17

State and Local Taxes Generated by Data Centers in Virginia ................................................................. 18

Statewide and Regional Tax Collections Associated with Data Centers ............................................... 19

Contribution to Local Government Budgets ....................................................................................... 19

High Local Benefit to Cost Ratio ..................................................................................................... 19

Reduces the Tax Burden on Local Residents and Lowers Tax Rates................................................. 21

Data Center Incentives in Virginia .......................................................................................................... 24

Virginia’s State Incentives .................................................................................................................. 24

JLARC’s Evaluation and Findings ..................................................................................................... 24

Virginia’s Incentive is One of the Most Restrictive .......................................................................... 26

JLARC’s Primary Recommendation ................................................................................................. 27

Incentives have been Instrumental in the Development of Virginia’s High-Tech Infrastructure ....... 28

The Incentive Helps to Attract Some Data Centers that Do Not Qualify for the Incentive................ 29

NVTC 2020 Data Center Report

Local Incentives ................................................................................................................................. 30

National Context for Virginia Incentives ................................................................................................. 32

Washington State Has Proven the Effectiveness of Incentives ............................................................ 33

Conclusion ............................................................................................................................................. 34

About Mangum Economics, LLC

Mangum Economics, LLC is a Richmond, Virginia based firm that specializes in producing objective

economic, quantitative, and qualitative analysis in support of strategic decision making. Much of our

recent work relates to IT & Telecom Infrastructure (data centers, terrestrial and subsea fiber),

Renewable Energy, and Economic Development. Examples of typical studies include:

POLICY ANALYSIS

Identify the intended and, more importantly, unintended consequences of proposed legislation and

other policy initiatives.

ECONOMIC IMPACT ASSESSMENTS AND RETURN ON INVESTMENT ANALYSES

Measure the economic contribution that businesses and other enterprises make to their localities.

WORKFORCE ANALYSIS

Project the demand for, and supply of, qualified workers.

CLUSTER ANALYSIS

Use occupation and industry clusters to illuminate regional workforce and industry strengths and

identify connections between the two.

The Project Team

A. Fletcher Mangum, Ph.D.

Founder and CEO

David Zorn, Ph.D.

Economist

Martina Arel, M.B.A.

Researcher and Economic Development Specialist

Kate Driebe

Research Assistant

NVTC 2020 Data Center Report

1

About the Northern Virginia Technology Council

The Northern Virginia Technology Council (NVTC) is the regional voice of technology, representing a

diverse and thriving technology ecosystem, promoting innovation, and convening, educating, and

advocating for the region's technology community.

NVTC is the membership and trade association for the technology community in Northern Virginia. As

the largest technology council in the nation, NVTC serves about 1,000 companies and organizations,

including businesses from all sectors of the technology industry, service providers, universities, foreign

embassies, non-profit organizations and government agencies. Through its member companies, NVTC

represents about 300,000 employees in the region. NVTC provides its members with:

• Over 150 networking and educational events per year.

• Comprehensive member benefit services.

• Public policy advocacy on a broad range of technology issues at the state and regional levels,

with involvement in federal issues as they relate to workforce and education concerns.

• Community service opportunities through involvement in community projects and philanthropy.

NVTC’s Data Center and Cloud Committee provides a clear, consistent, collective and compelling voice

for promoting the interests of the region's growing data center, cloud, and critical infrastructure

community to contribute to the long-term growth and prosperity of the industry. The committee:

• Promotes the interests of anyone with a stake in ensuring that Northern Virginia continues to be

a leading global destination not just for data centers but also for the wider ecosystem that relies

on the data center as the commerce platform of the 21st century.

• Provides educational and training programming for its members and provides forums for

thought leadership and the sharing of best practices.

• Leads efforts to identify the needs of the future workforce and advocates for industry-specific

education programming.

• Informs the community of the industry's vital role as a contributor to today's technology-led

economy and a major factor in the prosperity and economic stability of the region.

• Works to ensure the sustainability of the industry by thoughtfully discussing potential barriers to

growth and acts as an advocate for policies that prompt the overall health of the industry.

• Addresses the short- and long-term competitiveness of the data center industry in Virginia.

• Bolsters the data center and critical infrastructure industry through public policy advocacy.

• Promotes initiatives to increase data center investment and expansion throughout Virginia.

Acknowledgements

This report was made possible in part by the unique data supplied by the Loudoun County Department

of Economic Development (especially, Alex Gonski and Buddy Rizer), the Prince William County

Department of Economic Development (especially, Allisha Abraham, Thomas Flynn, and Jim Gahres),

and the Virginia Economic Development Partnership (especially, Brian Kroll).

NVTC 2020 Data Center Report

2

Executive Summary

Northern Virginia is the largest data center market in the world, but the data center industry has an

important footprint in every part of the Commonwealth of Virginia. Central Virginia and Hampton Roads

each account for almost ten percent of overall industry employment in the state. Data center industry

pay has increased twice as fast as the statewide average since 2001.

We estimate that in 2018 the data center industry in Virginia directly provided approximately:

• 14,644 full-time-equivalent jobs with an average annual pay of $126,000,

• $1.9 billion in associated pay and benefits, and

• $4.5 billion in economic output.

Taking into account the economic ripple effects that direct investment generated, we estimate that the

total impact on Virginia from the data center industry in 2018 was approximately:

• 45,290 full-time-equivalent jobs,

• $3.5 billion in associated pay and benefits, and

• $10.1 billion in economic output.

Data centers pay millions of dollars in state and local taxes in Virginia, even though Virginia has a sales

and use tax exemption on some equipment for data centers that are large enough to qualify for the

exemption. In addition to the taxes paid directly by data centers, local governments and the

Commonwealth of Virginia collect tax revenue from the secondary indirect and induced economic

activity that data centers generate. We estimate that in 2018, data centers were directly and indirectly

responsible for generating $600.1 million in state and local tax revenue in Virginia.

At the local level data centers provide far more in county or city tax revenue than they and their

employees demand in local government services. For example, we estimate that for every dollar in

county expenditures that the data center industry caused in 2018, it generated:

• $8.60 in local tax revenue in Henrico County, and property taxes there would have had to rise by

1 percent without the data center induced tax revenue.

• $15.10 in local tax revenue in Loudoun County, and property taxes there would have had to rise

by 21 percent without the data center induced tax revenue.

• $17.80 in tax revenue in Prince William County, and property taxes there would have had to rise

by 7 percent without the data center induced tax revenue.

In June of 2019, Virginia’s Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission (JLARC) published an

evaluation of the state’s data center sales and use tax incentive. JLARC found that 90 percent of the data

center investment made by the companies that received the sales and use tax exemption would not

have occurred in the state of Virginia without the incentive. Instead, that data center investment would

have occurred in other states. So, the “cost” of the State data center incentive is only 10 percent of the

amount of State sales tax revenue exempted. In fact, in 2017, the data center tax incentive generated

NVTC 2020 Data Center Report

3

$1.09 of State tax revenue for every dollar that it exempted; and in 2016, the incentive was revenue

neutral. Since 2013, after the General Assembly significantly revised the Virginia data center incentive,

the State has recovered 75 cents of every dollar of potential tax revenue that it exempted. In the

process it created thousands of Virginia jobs with billions of dollars in pay and benefits and billions of

dollars in economic activity throughout the state.

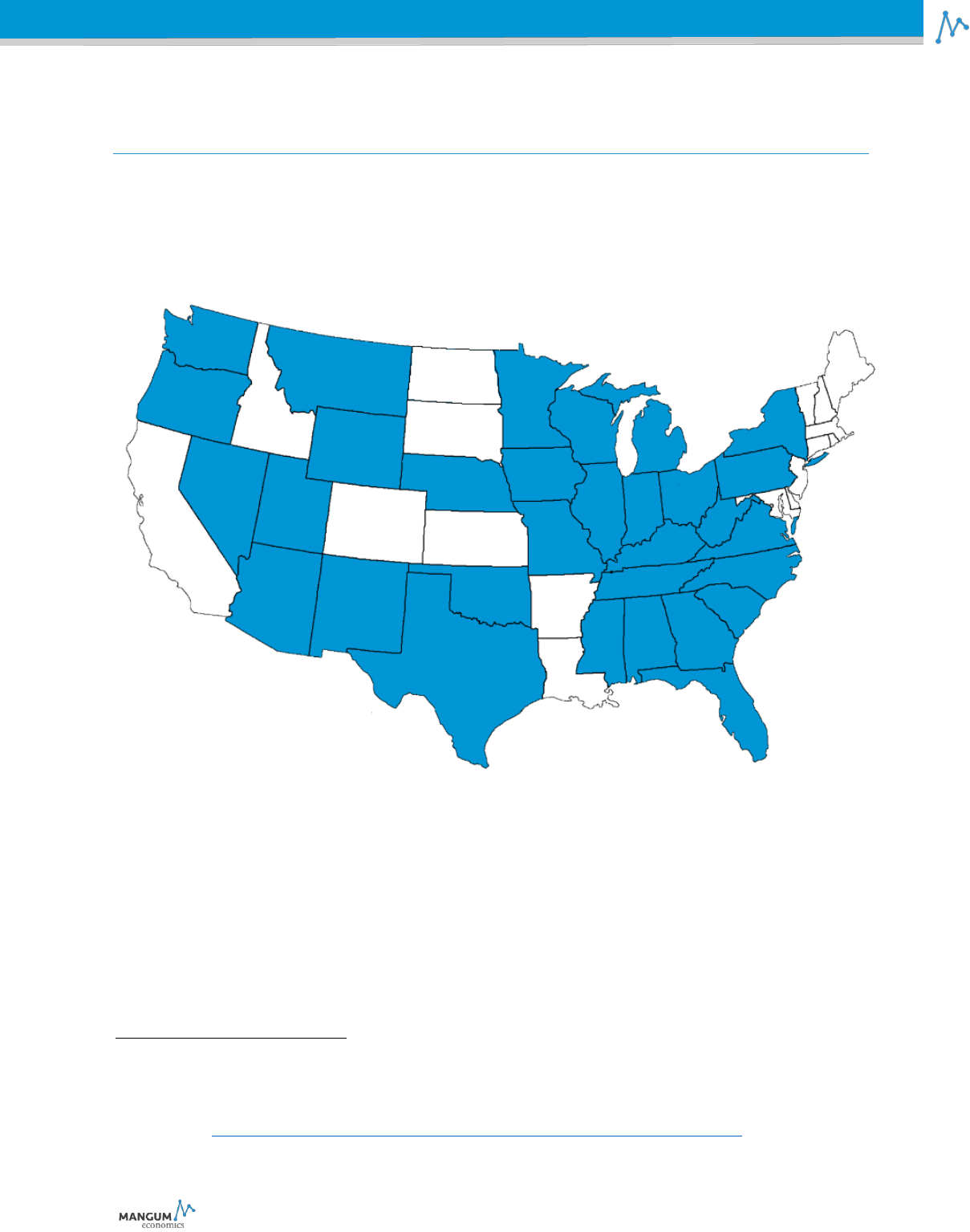

Virginia is one of 31 states that actively offer incentives to attract data centers to locate in their states.

Several states are in the process of revising their incentives to remain competitive. Virginia’s data center

incentive is one of the most restrictive in the country. Of the 31 states that actively offer data center

incentives, only 11 require a minimum number of new jobs to qualify for an incentive, and only Virginia,

Mississippi, and Nevada require the creation of 50 or more new jobs.

Virginia’s data center incentive has been important in the spread of technology industries across the

Commonwealth and in attracting smaller data centers that do not qualify for the incentive to invest in

the state as well. Recently several localities have reduced their local property tax rates in order to

attract data centers to support their economies.

NVTC 2020 Data Center Report

4

Introduction to Data Centers in Virginia

Life is increasingly digitized, and our digitized lives are stored, secured, processed, enhanced, and

distributed by data centers. Our finances, communications, health care, recreation, entertainment,

education, transportation, work, and social lives are often and increasingly online. Data centers are

more than just the redundant warehouses for our digital lives. They are also the generators of much of

the interactive digital content that we use. The personalized shopping recommendations; the on-the-fly

driving directions; the online assistance selecting a restaurant, hotel, plane flight; the digital grocery

coupons; the machine responses to banking and billing inquiries, etc. are all provided by data centers.

In 2012, IBM published an estimate that 90 percent of all data have been created in the last two years.

1

In other words, at that time, the total amount of data was increasing by ten times every two years. At

that rate, from 2010 to 2020 the total amount of data has increased by 100,000 times. Now consider

that the IBM estimate was made prior to the widespread adoption of commercial connected sensors

and smart consumer appliances. The expansion of artificial intelligence, machine learning, and

augmented reality are all putting increasing demands on data centers. So, it is quite likely that the rate

of growth of data is even greater than in 2012. We have not yet reached “peak data center.”

In addition, with the rollout of 5G technology to wireless networks, the shape of the industry will

change. Edge data centers that are relatively smaller than large cloud data centers will need to be

located near places where people congregate and move. However, edge data centers will not be

substitutes for large enterprise data centers or cloud data centers. Instead, edge data centers will be

constructed as a complement to large data centers as the data center industry continues to grow and

evolve to meet the demands of new technology.

Because data centers use large amounts of costly electricity and water, they have emerged as leading

innovators at the forefront of increasing operational efficiency in the use of energy and water.

2

Among

other innovations, data centers have used digitization, advanced sensors, and machine learning (within

data centers) to dramatically reduce energy and water consumption. For example, Google has been able

to reduce the amount of energy used for cooling in its data centers by up to 40 percent, reducing overall

energy usage in its data centers by 15 percent on top of previous efficiency enhancements.

3

Data center

companies have also made large commitments to the purchase of energy from renewable sources here

in Virginia and nationwide. For utility companies to move to different and initially costlier sources of

renewable power, they need this kind of commitment to provide a stable demand to ensure that the

large upfront investments that are required are financially sustainable.

This report quantifies the significant contribution that this dynamic and rapidly evolving industry makes

to the state of Virginia and its localities.

1

David Greer, “System z Helps Address the Data Analytics Power Crunch,” IBM Systems magazine, April 2012.

2

https://www.osti.gov/servlets/purl/1372902/

3

https://deepmind.com/blog/article/deepmind-ai-reduces-google-data-centre-cooling-bill-40

NVTC 2020 Data Center Report

5

ECONOMIC PROFILE OF DATA CENTERS IN VIRGINIA

Virginia now has data centers located throughout the state, from Wise County in Southwestern Virginia

and Harrisonburg in the Valley to Mecklenburg County in Southern Virginia, Virginia Beach in Hampton

Roads, and Henrico County in Central Virginia to Loudoun County in Northern Virginia, and other

localities. This report shows how the data center industry in every part of the state makes an important

economic contribution to employment and taxes in every region and to the state as a whole. However,

we begin with an update on the remarkable data center market in Northern Virginia.

The Northern Virginia Data Center Market in 2019

Northern Virginia has the largest data center market in the world. According to the latest data from

CBRE

4

, measured in megawatts (MW) of power capacity, Northern Virginia has more data center

inventory than the 6

th

through the 15

th

largest markets (New York Tri-State, Atlanta, Austin-San Antonio,

Houston, Southern California, Seattle, Denver, Boston, Charlotte-Raleigh, and Minneapolis) combined

and almost as much as the 2

nd

, 3

rd

, 4

th

and 5

th

largest markets (Dallas-Fort Worth, Silicon Valley, Chicago,

and Phoenix) combined.

The large capacity of Northern Virginia’s data center market is matched by its growth. Twenty-two

percent of the total data center capacity in Northern Virginia was added between the second half of

2018 and the first half of 2019.

The growth in the Northern Virginia data center market has not only served technology, data center,

and data dependent companies, but construction companies.

Northern Virginia’s place at the top of the data center market is a relatively recent development. In

2016, Northern Virginia had just supplanted the New York market as the largest data center market in

the United States. In 2017, the New York Tri-State area had fallen to the sixth largest data center

market. A 2011 report on the data center market in the United States contains only one mention of

Virginia in four pages – “Reston, VA has excess supply and new construction will be minimal for a few

years.”

5

The locations that were highlighted as important in the industry were Chicago, Silicon Valley,

Southern California, Phoenix, New York, St. Louis, Washington State, Boston, Minneapolis, Denver, and

Charlotte. Regarding what has become the second largest data center market, the report says, “Dallas

has excess capacity and growth remains slow.”

This illustrates the fluid nature of the data center industry and the speed with which market conditions

can change in the industry. Once hot markets can cool off rapidly. A year ago, the data center market in

Phoenix had enormous growth, but between the second half of 2018 and the first half of 2019, Phoenix

saw net outflows of 26.5 MW worth of tenants, which is almost the same amount that Northern Virginia

4

CBRE, Large Supply Pipeline Sets Stage for Market Growth in 2019 North American Data Center Report H1 2019.

5

ESD (Environmental Systems Design, Inc.), 2011 Data Center Technical Market Report. February 2011.

NVTC 2020 Data Center Report

6

added in the same period.

6

The computer equipment in data centers is replaced on average every three

years. Should circumstances require it, data center tenants can move from one location to another and

leave significant vacancies in colocation data centers.

Figure 1 shows the top 15 largest data center markets in the United States. The area of each circle

indicates the relative amount of power capacity (MW labeled in black) in each market. Brighter blue

circles indicate markets with higher occupancy rates, with Austin-San Antonio, Silicon Valley, and

Northern Virginia having occupancy rates of about 96 to 93 percent (in order of occupancy).

Figure 1. Relative Sizes of Largest Data Center Markets (megawatts of power capacity) – 2019

7

6

CBRE, Large Supply Pipeline Sets Stage for Market Growth in 2019 North American Data Center Report H1 2019.

7

CBRE, Large Supply Pipeline Sets Stage for Market Growth in 2019 North American Data Center Report H1 2019.

NVTC 2020 Data Center Report

7

The Regional Distribution of Data Centers in Virginia

The Virginia Economic Development Partnership (VEDP) provided data on the private sector Data

Processing, Hosting, and Related Services industry (as defined by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics) for

this economic profile.

8

VEDP divided the statewide data into six sub-state regions depicted in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Six Sub-State Regions Defined by the Virginia Economic Development Partnership

According to VEDP, in 2018, the private sector data center industry employed 14,644 people (full-time

equivalents) statewide.

8

As is common practice, we use the Data Processing, Hosting, and Related Services industry as defined by the U.S. Bureau of

Labor Statistics as a proxy for the data center industry. The data and methods applied in this report are described in the

separate accompanying Appendix.

NVTC 2020 Data Center Report

8

Figure 3 shows the regional distribution of that employment. Seventy-five percent of data center

employment was located in Northern Virginia. However, industry employment was distributed across

other regions of the Commonwealth, as well. Central Virginia and Hampton Roads accounted for nine

percent of data center jobs each. Southern Virginia (home to Microsoft’s Boydton data center campus,

the east coast hub for Microsoft Azure) accounted for four percent of private sector data center

employment, one percent of industry employment was in Southwestern Virginia, and two percent was

in the Valley.

Figure 3. Regional Distribution of Private Sector Data Center Employment in Virginia in 2018

9

The Upward Trend in Virginia’s Data Center Industry

Data center employment in Virginia generally declined between 2004 and 2012, but it has since

escalated rapidly to 14,644 jobs in 2018.

10

That change to the uptrend in employment that began in

2012 coincides with the year that Virginia significantly revised its data center incentive to make it more

competitive with other states in attracting data centers. More detail on the employment trends in the

industry is included in the separate Appendix that accompanies this report.

9

Data Source: Virginia Economic Development Partnership.

10

Data Source: Virginia Economic Development Partnership.

Central VA: 9%

Hampton Roads: 9%

Northern VA: 75%

Southern VA: 4%

Southwestern VA: 1%

Valley: 2%

NVTC 2020 Data Center Report

9

The High-Performance Data Center Industry in Virginia

One of the key characteristics of the data center industry is that it is extremely capital intensive. In other

words, the industry employs a relatively small number of highly skilled and highly paid people to operate

and maintain a very large amount of very expensive equipment. Therefore, it is useful to also look at

trends in private sector average annual wages in the industry.

Between 2001 and 2018 the average annual private sector wage in the data center industry in Virginia

grew from $61,310 to $126,050 – a 106 percent increase.

11

In comparison, over the same period

average private wages across all industries in Virginia went from $36,525 to $57,846 – an increase of 58

percent.

12

In other words, over the 18-year period, the average private sector employee of a Virginia

data center saw their gross income go up almost twice as fast as the average private sector employee in

Virginia. More detail on the employment trends in the industry is included in the separate Appendix that

accompanies this report.

This combination of steadily rising employment and rapidly rising wages make the data center industry

one of Virginia’s most high-performance industries and an important (and growing) contributor to a

strong and robust state economy. Moreover, in a state such as Virginia where roughly two-thirds of

state revenue comes from personal income tax, high growth/high wage industries such as the data

center industry also play a disproportionate role in ensuring the health of the State’s budget.

The Impact of Data Centers on Virginia State and Local Economies

The construction and ongoing operation of data centers in Virginia has large, broad effects across the

state economy. In this section, we estimate the statewide economic impact that the data center

industry has on Virginia, as well as in each of the six sub-state regions detailed earlier. To empirically

evaluate the statewide and regional economic impact attributable to the data center industry, we

employ a commonly used regional economic impact model called IMPLAN Pro.

13

The methodology for

modeling the economic impact of data centers is explained in more detail in the separate Appendix that

accompanies this report.

Regional economic impact modeling measures the ripple effects that an expenditure generates as it

makes its way through the economy. For this report, spending by the data center industry in Virginia has

a direct economic impact on the state economy in terms of people hired as data center employees,

employee pay and benefits, and economic activity in the region for utilities, construction, and

equipment. That direct spending by the data centers creates the first ripple of economic activity.

11

Data Source: Virginia Economic Development Partnership.

12

Data Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

13

IMPLAN Pro is produced by IMPLAN Group, LLC.

NVTC 2020 Data Center Report

10

As data center employees and businesses (like construction contractors for data centers, power

companies that supply data centers, and data center equipment suppliers) spend the money that they

were paid by data center companies, they create another indirect ripple of economic activity that is part

of the second-round effects of the data center industry.

There are many Virginia businesses that are part of the data center supply chain. To illustrate some of

the types of companies located in Virginia that benefit from the data center industry in Virginia and that,

in turn, generate economic activity in the state, in Table 1 we list a few different types of businesses in

the Virginia data center supply chain. The list of businesses in Table 1 is not an endorsement, promotion,

or commendation of them, and it is far from a complete list of companies. We only provide it to

illustrate some of the types of businesses that are part of the second ripple effect of economic activity

related to spending by data centers.

Table 1. Some Businesses Serving Virginia Data Centers

Company

Line of Business

Anord Mardix

data center power distribution and management products and services

Compu Dynamics

data center design, construction, optimization, and maintenance

Fulcrum Collaborations

data center facilities management cloud-based platform

Hanley Energy

data center energy management services

Interglobix

data center and fiber interconnectivity consulting and marketing

Metro Fiber Networks

carrier-neutral fiber connecting Virginia Beach to Henrico data centers

Power Distribution

Incorporated

data center power transformation, distribution, and monitoring

Rosendin Electric

data center design and construction services

Submer

data center IT hardware immersion cooling

Technoguard

data center materials, cleaning, decontamination, and disaster recovery

Timmons Group

data center site certification and development

Windward Consulting

data center management consulting

In addition to the economic effects in the Virginia state and local economies of the data center-to-other

business transactions, there are also the second-round economic effects associated with data center

employee-to-business transactions that ripple through local economies. These effects occur when data

center employees buy groceries; pay rent; go out for dinner, entertainment, or other recreation; pay for

schooling in Virginia; or make other local purchases. Additionally, there are the second-round economic

effects of business-to-business transactions between the direct vendors to data centers and their

suppliers.

NVTC 2020 Data Center Report

11

The total impact is simply the sum of the first round direct and second round impacts. These categories

of impact are then further defined in terms of employment (the jobs that are created), labor income

(the pay and benefits associated with those jobs), and economic output (the total amount of economic

activity that is created in the economy).

VIRGINIA STATEWIDE

We estimate that in 2018 the data center industry in Virginia directly provided approximately:

• 14,644 full-time-equivalent jobs,

• $1.9 billion in associated employee pay and benefits, and

• $4.5 billion in economic output.

Taking into account the economic ripple effects generated by that direct impact, we estimate that the

total impact on Virginia from the data center industry in 2018 was approximately:

• 45,290 full-time-equivalent jobs,

• $3.5 billion in associated employee pay and benefits, and

• $10.1 billion in economic output.

Table 2. Economic Impact of the Data Center Industry in Virginia in 2018 (2018 dollars)

1

st

Round Direct Effects

Jobs

Pay

Economic Output

Data Centers

14,644

14

$1,908,963,000

$4,541,390,000

2

nd

Round Indirect and Induced Effects

15

Operations

23,796

$1,223,797,000

$4,566,184,000

Healthcare

1,932

$152,433,000

$292,468,000

Construction

4,918

$263,018,000

$690,126,000

16

Total Impact

Total Economic Impact in Virginia Statewide

17

45,290

$3,548,212,000

$10,090,168,000

14

Data Source: Virginia Economic Development Partnership.

15

The methodology for estimating and characterizing 2

nd

round effects is described in detail in the separate Appendix that

accompanies this report.

16

Derived from Virginia Economic Development Partnership Announcements.

17

The statewide estimates of jobs, pay, and economic output is larger than the sum of the individual regional estimates

reported separately in the following tables because the regional totals only register jobs, pay, and economic output in a region

caused by the direct data center investment in the same region. The regional amounts do not count jobs, pay, and economic

output generated in one region caused by direct data center investment that occurred in another region.

NVTC 2020 Data Center Report

12

CENTRAL VIRGINIA

We estimate that in 2018 the data center industry in Central Virginia directly provided approximately:

• 1,275 full-time-equivalent jobs,

• $141.5 million in associated employee pay and benefits, and

• $341.4 million in economic output.

Taking into account the economic ripple effects generated by that direct impact, we estimate that the

total impact on Central Virginia from the data center industry in 2018 was approximately:

• 5,248 full-time-equivalent jobs,

• $347 million in associated employee pay and benefits, and

• $1 billion in economic output.

Table 3. Economic Impact of the Data Center Industry in Central Virginia in 2018 (2018 dollars)

1

st

Round Direct Effects

Jobs

Pay

Economic Output

Data Centers

1,275

18

$141,500,000

$341,382,000

2

nd

Round Indirect and Induced Effects

19

Operations

2,042

$105,729,000

$407,868,000

Healthcare

144

$11,812,000

$22,584,000

Construction

1,787

$87,949,000

$244,267,000

20

Total Impact

Total Economic Impact in Central Virginia

5,248

$346,990,000

$1,016,102,000

18

Data Source: Virginia Economic Development Partnership.

19

The methodology for estimating and characterizing 2

nd

round effects is described in detail in the separate Appendix that

accompanies this report.

20

Derived from Virginia Economic Development Partnership Announcements.

NVTC 2020 Data Center Report

13

HAMPTON ROADS

We estimate that in 2018 the data center industry in Hampton Roads directly provided approximately:

• 1,322 full-time-equivalent jobs,

• $72.6 million in associated employee pay and benefits, and

• $329.4 million in economic output.

Taking into account the economic ripple effects generated by that direct impact, we estimate that the

total impact on Hampton Roads from the data center industry in 2018 was approximately:

• 3,510 full-time-equivalent jobs,

• $166.2 million in associated employee pay and benefits, and

• $667.6 million in economic output.

Table 4. Economic Impact of the Data Center Industry in Hampton Roads in 2018 (2018 dollars)

1

st

Round Direct Effects

Jobs

Pay

Economic Output

Data Centers

1,322

21

$72,565,000

$329,362,000

2

nd

Round Indirect and Induced Effects

22

Operations

1,804

$73,436,000

$287,200,000

Healthcare

76

$5,466,000

$10,764,000

Construction

309

$14,775,000

$40,288,000

23

Total Impact

Total Economic Impact in Hampton Roads

3,510

$166,241,000

$667,614,000

21

Data Source: Virginia Economic Development Partnership.

22

The methodology for estimating and characterizing 2

nd

round effects is described in detail in the separate Appendix that

accompanies this report.

23

Derived from Virginia Economic Development Partnership Announcements.

NVTC 2020 Data Center Report

14

NORTHERN VIRGINIA

We estimate that in 2018 the data center industry in Northern Virginia directly provided approximately:

• 10,663 full-time-equivalent jobs,

• $1.6 billion in associated employee pay and benefits, and

• $3.5 billion in economic output.

Taking into account the economic ripple effects generated by that direct impact, we estimate that the

total impact on Northern Virginia from the data center industry in 2018 was approximately:

• 28,196 full-time-equivalent jobs,

• $2.6 billion in associated employee pay and benefits, and

• $6.9 billion in economic output.

Table 5. Economic Impact of the Data Center Industry in Northern Virginia in 2018 (2018 dollars)

1

st

Round Direct Effects

Jobs

Pay

Economic Output

Data Centers

10,663

24

$1,554,239,000

$3,517,485,000

2

nd

Round Indirect and Induced Effects

25

Operations

13,692

$786,373,000

$2,744,347,000

Healthcare

1,397

$121,517,000

$221,932,000

Construction

2,445

$163,753,000

$382,561,000

26

Total Impact

Total Economic Impact in Northern Virginia

28,196

$2,625,883,000

$6,866,325,000

The Northern Virginia Community College Programs

Northern Virginia Community College (NOVA) has developed programs to help address the challenges

that data centers in the Northern Virginia area have meeting their staffing needs. Amazon Web Services

(AWS) has a paid apprenticeship program at the NOVA.

27

In December 2018, the program graduated its

first students into full-time Associate Cloud Consultant jobs with AWS.

NOVA also has a 2-year Associate of Applied Science program to train Datacenter Operations

Technicians.

28

The program includes lab training at a training data center that the State of Virginia built

on the NOVA-Loudoun Campus. The program started with 19 students in its very first year, almost half

of them have already found internships or full-time jobs in Northern Virginia data centers or full-time

jobs with companies that work for data centers.

24

Data Source: Virginia Economic Development Partnership.

25

The methodology for estimating and characterizing 2

nd

round effects is described in detail in the separate Appendix that

accompanies this report.

26

Derived from Virginia Economic Development Partnership Announcements.

27

NOVA, “Amazon and Northern Virginia Community College Announce Graduation of the First Veteran Technical

Apprenticeship Cohort on the East Coast,” December 12, 2018.

28

NOVA 2019-2020 Catalog, Engineering Technology: Data Center Operations Specialization, A.A.S.

NVTC 2020 Data Center Report

15

SOUTHERN VIRGINIA

We estimate that in 2018 the data center industry in Southern Virginia directly provided approximately:

• 568 full-time-equivalent jobs,

• $33 million in associated employee pay and benefits, and

• $137.2 million in economic output.

Taking into account the economic ripple effects generated by that direct impact, we estimate that the

total impact on Southern Virginia from the data center industry in 2018 was approximately:

• 1,236 full-time-equivalent jobs,

• $57.5 million in associated employee pay and benefits, and

• $237.4 million in economic output.

Table 6. Economic Impact of the Data Center Industry in Southern Virginia in 2018 (2018 dollars)

1

st

Round Direct Effects

Jobs

Pay

Economic Output

Data Centers

568

29

$33,030,000

$137,223,000

2

nd

Round Indirect and Induced Effects

30

Operations

637

$22,286,000

$96,006,000

Healthcare

32

$2,228,000

$4,159,000

Construction

31

Total Impact

Total Economic Impact in Southern Virginia

1,236

$57,544,000

$237,388,000

29

Data Source: Virginia Economic Development Partnership.

30

The methodology for estimating and characterizing 2

nd

round effects is described in detail in the separate Appendix that

accompanies this report.

31

VEDP registered no data center investment announcements in 2018 in Southern Virginia, and therefore we do not estimate

construction activity in the area. However, it is important to note that we attribute construction only to the first year of an

announcement and, unlike ongoing data center operations, construction is episodic. For example, we estimate that as recently

as 2016, Southern Virginia enjoyed approximately $50 million in data center construction. This estimate may actually

understate the actual economic impact of data center construction.

NVTC 2020 Data Center Report

16

SOUTHWESTERN VIRGINIA

We estimate that in 2018 the data center industry in Southwestern Virginia directly provided

approximately:

• 135 full-time-equivalent jobs,

• $8.6 million in associated employee pay and benefits, and

• $28.9 million in economic output.

Taking into account the economic ripple effects generated by that direct impact, we estimate that the

total impact on Southwestern Virginia from the data center industry in 2018 was approximately:

• 257 full-time-equivalent jobs,

• $13.1 million in associated employee pay and benefits, and

• $45.8 million in economic output.

Table 7. Economic Impact of the Data Center Industry in Southwestern Virginia in 2018 (2018 dollars)

1

st

Round Direct Effects

Jobs

Pay

Economic Output

Data Centers

135

32

$8,552,000

$28,869,000

2

nd

Round Indirect and Induced Effects

33

Operations

113

$3,940,000

$15,787,000

Healthcare

8

$532,000

$1,031,000

Construction

1

$27,000

$80,000

34

Total Impact

Total Economic Impact in Southwestern

Virginia

257

$13,051,000

$45,767,000

32

Data Source: Virginia Economic Development Partnership.

33

The methodology for estimating and characterizing 2

nd

round effects is described in detail in the separate Appendix that

accompanies this report.

34

Derived from Virginia Economic Development Partnership Announcements. However, it is important to note that we

attribute construction only to the first year of an announcement and, unlike ongoing data center operations, construction is

episodic. This estimate may actually understate the actual economic impact of data center construction.

NVTC 2020 Data Center Report

17

VALLEY

We estimate that in 2018 the data center industry in the Valley directly provided approximately:

• 191 full-time-equivalent jobs,

• $14.3 million in associated employee pay and benefits, and

• $46.1 million in economic output.

Taking into account the economic ripple effects generated by that direct impact, we estimate that the

total impact on the Valley from the data center industry in 2018 was approximately:

• 461 full-time-equivalent jobs,

• $24.9 million in associated employee pay and benefits, and

• $86.6 million in economic output.

Table 8. Economic Impact of the Data Center Industry in the Valley in 2018 (2018 dollars)

1

st

Round Direct Effects

Jobs

Pay

Economic Output

Data Centers

191

35

$14,255,000

$46,088,000

2

nd

Round Indirect and Induced Effects

36

Operations

255

$9,555,000

$38,439,000

Healthcare

15

$1,046,000

$2,041,000

Construction

37

Total Impact

Total Economic Impact in the Valley

461

$24,856,000

$86,568,000

35

Data Source: Virginia Economic Development Partnership.

36

The methodology for estimating and characterizing 2

nd

round effects is described in detail in the separate Appendix that

accompanies this report.

37

No data center investment announcements were made in 2018 in the Valley. However, it is important to note that we

attribute construction only to the first year of an announcement and, unlike ongoing data center operations, construction is

episodic. This estimate may actually understate the actual economic impact of data center construction.

NVTC 2020 Data Center Report

18

State and Local Taxes Generated by Data Centers in Virginia

Data centers pay millions of dollars in state and local taxes in Virginia, even though Virginia has a sales

and use tax exemption on some equipment for data centers that are large enough to qualify for the

exemption. All data centers (large and small) pay state employer withholding taxes and corporate

income tax. At the local level, both large and small data centers pay real estate taxes, tangible personal

property taxes, business license taxes, and industrial utilities taxes. Additionally, many data centers still

must pay state sales and use taxes on their purchases of data center equipment because they are not

large enough to qualify for the Virginia data center incentive.

In addition to the taxes that data centers pay directly, the economic activity that they generate also

results in additional tax collections. Figure 4 illustrates the sources of tax revenues associated with data

centers. On the bottom row, data centers pay taxes directly to federal, state, and local governments. On

the second row, the employees and business suppliers that are paid directly by the data centers also pay

taxes; and, additionally, on the third row, the people and businesses that are paid by the employees and

suppliers of data centers pay taxes. All of these sources of tax revenue are included in the tax revenue

estimates described in this report.

Figure 4. Sources of Tax Revenue Associated with Data Centers

NVTC 2020 Data Center Report

19

STATEWIDE AND REGIONAL TAX COLLECTIONS ASSOCIATED WITH DATA CENTERS

In addition to the taxes paid directly by data centers, local governments and the Commonwealth of

Virginia collect tax revenue from the secondary indirect and induced economic activity that data centers

generate. Table 9 shows our estimates of the taxes directly and indirectly generated by the data center

industry statewide in Virginia and in each of the six sub-state regions in 2018 through that first round

and second round economic activity.

We estimate that in 2018, data centers were directly and indirectly responsible for generating $600.1

million in state and local tax revenue in Virginia.

Table 9. Tax Revenue Directly and Indirectly Generated by the Data Centers Industry in Virginia in 2018

Region

State and Local Taxes

Collected

Federal Taxes

Collected

Total Taxes

Collected

Central Virginia

$37,231,000

$83,069,000

$120,300,000

Hampton Roads

$21,260,000

$38,624,000

$59,885,000

Northern Virginia

$460,534,000

$587,517,000

$1,048,051,000

Southern Virginia

$7,823,000

$13,643,000

$21,466,000

Southwestern Virginia

$1,469,000

$2,945,000

$4,414,000

Valley

$2,985,000

$5,745,000

$8,731,000

Virginia Statewide

38

$600,120,000

$812,308,000

$1,412,428,000

CONTRIBUTION TO LOCAL GOVERNMENT BUDGETS

Because the data centers need more equipment and utilities than they need employees, the data center

industry provides a large amount of property tax revenue for local governments. Additionally, the

industry also places downward pressure on overall tax rates, thereby improving the locality’s business

climate and economic attractiveness.

High Local Benefit to Cost Ratio

Data centers provide a high benefit to cost ratio in terms of the tax revenue they generate relative to

the government services that they and their employees require. Loudoun County, Prince William

County, and Henrico County are home to the most significant concentrations of data centers in Virginia.

County staff in those localities were able to provide us with detailed data on the tax revenue generated

by this industry in each locality from real and business personal property taxes.

39

As a result, we are able

38

The statewide estimates of taxes collected is larger than the sum of the taxes collected in the individual regions separately

because the regional totals only register tax revenue in a region caused by the direct data center investment in the same

region. The regional amounts do not count taxes generated in one region caused by direct data center investment that

occurred in another region.

39

It should be noted that, of necessity, these estimates exclude BPOL and other local taxes that also apply to the data center

industry. As a result, the revenue estimates provided almost certainly under-estimate the actual local tax revenues of the data

center industry.

NVTC 2020 Data Center Report

20

to use those data in combination with data from other sources to compute the benefit to cost ratio

associated with the data center industry in each locality.

To quantify the budgetary cost that the data center industry and its employees imposed on these

localities in 2018, we use data from the Virginia Department of Education on local elementary and

secondary education expenditures per student, and data from the Virginia Auditor of Public Accounts on

local non-education expenditures per county resident. This approach focuses on the largest costs that

any business imposes on a local government – the costs associated with providing primary and

secondary education, and other county services, to the employees of that business.

Table 10 details the calculations used to estimate the budgetary cost that the data center industry and

its employees imposed on each of these three counties in 2018. As shown, we estimate those costs to

be approximately $400,000 in Henrico County, $17.7 million in Loudoun County, and $2 million in Prince

William County.

Table 10. Estimate of Total Budgetary Costs Imposed by the Data Center Industry and Employees in 2018

Henrico

County

Loudoun

County

Prince

William

County

County Private Sector Employment in Data

Processing, Hosting, and Related Services in 2018

40

115

2,278

241

Students per Employee

41

0.27

0.48

0.69

Per Student County Education Expenditures

42

$4,852

$10,069

$5,296

Total Education Costs

43

$150,000

$11,005,000

$886,000

County Residents per Employee

44

1.72

2.41

3.59

Per Resident Non-Education County Expenditures

45

$1,477

$1,216

$1,294

Total Non-Education Costs

46

$292,000

$6,667,000

$1,120,000

TOTAL COSTS

47

$442,000

$17,672,000

$2,006,000

40

Data Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

41

Data Source: Virginia Department of Education and U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Derived by dividing total county

elementary and secondary school enrollment in 2018 by total county employment in 2018.

42

Data Source: Virginia Department of Education.

43

Calculated as county private sector employment in the data center industry in 2018, times students per employee, times per

student education expenditures.

44

Data Source: U.S. Census Bureau and U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Calculated by dividing total county population in 2018 by

total county employment in 2018.

45

Data Source: Virginia Auditor of Public Accounts and U.S. Census Bureau. Derived by dividing total county non-educational

expenditures in 2018 by total county population in 2018.

46

Derived as county private sector employment in the data center industry in 2018, times county residents per employee, times

per resident non-education expenditures.

47

Derived as the sum of total education costs and total non-education costs.

NVTC 2020 Data Center Report

21

As shown in Table 11, combining the estimates of budgetary cost from Table 9 with data from each of

the localities on the local revenue generated by the data center industry shows that in 2018 the

benefit/cost ratio associated with the industry was:

• 8.6 in Henrico County. Which means that for every $1.00 in county expenditures that the data

center industry was responsible for generating in 2018, it provided approximately $8.60 in tax

revenue.

• 15.1 in Loudoun County. Which means that for every $1.00 in county expenditures that the data

center industry was responsible for generating in 2018, it provided approximately $15.10 in tax

revenue.

• 17.8 in Prince William County. Which means that for every $1.00 in county expenditures that the

data center industry was responsible for generating in 2018, it provided approximately $17.80 in

tax revenue.

Table 11. Estimated Benefit/Cost Ratio Associated with the Data Center Industry and Employees in 2018

Locality

Estimated Tax

Revenue (Benefit)

Estimated Budgetary

Cost

Benefit/Cost Ratio

Henrico County

$3,784,000

$442,000

8.6

Loudoun County

$266,623,000

$17,672,000

15.1

Prince William County

$35,802,000

$2,006,000

17.8

Reduces the Tax Burden on Local Residents and Lowers Tax Rates

One of the most useful concepts in economics is the concept of opportunity cost – what is the cost of

not doing something? Or in this case, what would have been the cost to these localities if their data

centers had not existed in 2018? The obvious answer is that they would not have received the estimated

$306.2 million in county tax revenue that this industry provided in 2018. Therefore, in order to maintain

county expenditures at the same level, that revenue would have had to come from other sources. The

two most likely sources would have been: 1) additional education funding from the state triggered by

the negative impact that this loss in tax base would have had on the composite index formula Virginia

uses to allocate education funding to localities, and 2) an increase in each county’s real property tax

rate.

On average, the state of Virginia funds 55 percent of primary and secondary education expenditures,

and localities are required to locally fund the remaining 45 percent.

48

But, that local funding percentage

is adjusted up or down based on each locality’s “ability to pay” as measured by Virginia’s composite

index formula that takes into account the locality’s property tax base, adjusted gross income, and

48

In actuality, however, baseline local funding percentages are typically higher than 45 percent because of local initiatives.

NVTC 2020 Data Center Report

22

taxable retail sales. Of these three factors, property tax base receives the highest weight (50 percent)

and, therefore, has the largest influence on the final calculation.

49

The 2018 composite index for Henrico County was 0.4183, for Loudoun County 0.5383 and for Prince

William County 0.3783.

50

If we recalculate those indexes to take into account the loss of tax base implied

by the $306.2 million loss in tax revenue that would have occurred if the data center industry had not

existed in these localities, those indexes fall to 0.4162, 0.5065, and 0.3692 respectively.

As shown in Table 12, according to our estimates, this means that the state would have had to reallocate

$55.8 million in state education funding away from other Virginia localities to provide $1 million in

additional formula-driven funding to Henrico County, $44.3 million in additional funding to Loudoun

County, and $10.5 million in additional funding to Prince William County.

Table 12. Estimated Additional Revenue Required to Compensate for Loss of the Data Center Industry in

2018 by Source

Locality

Revenue Loss

State Education

Funding Off-Set

Additional Local Tax

Revenue Required

from Other Sources

Henrico County

($3,784,000)

$1,043,000

$2,741,000

Loudoun County

($266,623,000)

$44,285,000

$223,338,000

Prince William County

($35,802,000)

$10,465,000

$25,337,000

Total*

($306,210,000)

$55,794,000

$250,416,000

*May not sum due to rounding

49

Virginia Department of Education. The actual formula weights each locality’s property tax base by 0.5, adjusted gross income

by 0.4, and taxable retail sales by 0.1. Each metric is then divided by school population and total population and those per

capita figures are divided by the average across all localities to determine ability to pay. The per capita figures are then

themselves weighted with each per capita school population metric receiving a weight of 0.66 and each per capita population

metric receiving a weight of 0.33.

50

Virginia Department of Education.

NVTC 2020 Data Center Report

23

The remaining $250.4 million in lost tax revenue would likely have been made up through increased

property taxes (by far the largest source of revenue for most localities). Figure 8 depicts our estimate of

the increase in each County’s real property tax rates that would have been required to generate this

$250.4 million in lost tax revenue. As shown:

• Henrico County’s real property tax rate would have likely had to increase from $0.870 per $100

of assessed value to $0.883 (a 1 percent increase),

• Loudoun County’s real property tax rate would have likely had to increase from $1.085 per $100

of assessed value to $1.313 (a 21 percent increase), and

• Prince William County’s would have likely had to increase from $1.125 per $100 of assessed

value to $1.200 (a 7 percent increase).

Figure 5. Estimated County Real Property Tax Rates per $100 of Assessed Value with and without the

Data Center Industry

$0.870

$1.085

$1.125

$0.883

$1.313

$1.200

$0.00

$0.20

$0.40

$0.60

$0.80

$1.00

$1.20

$1.40

Henrico County Loudoun County Prince William County

With Data Centers Without Data Centers

NVTC 2020 Data Center Report

24

Data Center Incentives in Virginia

Data centers in Virginia can qualify for two types of incentives: those offered by the state of Virginia and

those offered by individual localities.

VIRGINIA’S STATE INCENTIVES

At the state level, two incentives are offered: a sales and use tax exemption and a single sales

apportionment incentive. According to the Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission (JLARC), the

single sales apportionment incentive has not been used by any data centers as of fiscal year 2017 (the

latest year that data is available), so we will not give more attention to it in this report.

51

The sales and use tax exemption is available to data centers that make a minimum new capital

investment of $150 million and that create a minimum of 50 new jobs in a Virginia locality. If the data

center is located in an enterprise zone or in a locality with an unemployment rate at least 1.5 times the

average statewide unemployment rate, the minimum new job requirement is reduced to 25. Each new

job must pay at least 150 percent of the annual average wage in the locality where the data center

is located. Tenants of colocation data centers that qualify for the incentive may also receive the sales

and use tax exemption. According to the JLARC, as of fiscal year 2017, 24 data centers had qualified for

the incentive, plus 135 colocation data center tenants.

52

According to JLARC’s latest report, in fiscal year

2018, $86 million of sales and use tax was exempted under the incentive.

53

JLARC’s Evaluation and Findings

In June of 2019, Virginia’s Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission published an evaluation of the

state’s data center incentive using confidential tax information that is not publicly available.

54

JLARC found that 90 percent of the data center investment made by the companies that received the

sales and use tax exemption would not have occurred in the state of Virginia without the incentive.

Instead, that 90 percent of data center investment would have occurred in states other than Virginia. So,

the “cost” of the State data center incentive is only 10 percent of the amount of State sales tax revenue

exempted. Using the confidential tax information, JLARC estimated the economic and government

budgetary impact, not of the total data center industry in Virginia (as we have done in this report), but

specifically, of Virginia’s data center sales and use tax exemption.

55

51

Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission, Data Center and Manufacturing Incentives Economic Development Incentives

Evaluation Series. June 17, 2019. (JLARC, Data Center Evaluation)

52

Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission, Data Center and Manufacturing Incentives, Economic Development Incentives

Evaluation Series. June 17, 2019.

53

Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission, Economic Development Incentives 2019, Spending and Performance.

December 16, 2019.

54

Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission, Data Center and Manufacturing Incentives, Economic Development Incentives

Evaluation Series. June 17, 2019.

55

Appendix N: Results of economic and revenue impact analyses.

NVTC 2020 Data Center Report

25

Table 13 shows the text of Appendix N from the JLARC report with JLARC’s calculations of the amount of

State tax revenue exempted by the Virginia incentive; the amount of additional State tax revenue that

was generated by the investment of the data centers that received the tax incentive; the net impact of

the incentive on the State budget (additional tax received minus tax revenue exempted); net new jobs

added, net additional state gross domestic product (GDP) generated, and net new worker pay generated

throughout the statewide economy as a result of the investment by data centers that received the

incentive. Table 13 shows data for the fiscal years 2013 through 2017. This is the most recent data

available that covers the years when the current version of Virginia’s data center incentive has been

implemented. The General Assembly made significant revisions to the data center incentive in 2012.

Table 13. Economic and Tax Impacts of Virginia’s Sales and Use Tax Exemption for Data Centers

56

With Data

Center

Incentive

FY2013

FY2014

FY2015

FY2016

FY2017

State Tax

Revenue

Exempted

($81,298,000)

($80,131,000)

($93,249,000)

($54,757,000)

($54,516,000)

Additional State

Tax Revenue

$44,548,000

$49,705,000

$64,494,000

$54,742,000

$59,171,000

Net State

Budgetary

Impact

($36,751,000)

($30,426,000)

($28,755,000)

($15,000)

$4,655,000*

State Revenue

Recovered per

$1 of State

Revenue

Exempted

$0.55

$0.62

$0.69

$1.00

$1.09

Net Additional

Jobs

11,631

12,168

14,138

9,968

10,324

Net Additional

State GDP

$1,594,238,000

$1,838,394,000

$2,268,541,000

$1,862,303,000

$2,028,606,000

Net Additional

Worker Pay

$852,123,000

$987,672,000

$1,238,666,000

$1,022,226,000

$1,126,545,000

* In 2017, the data center tax incentive generated more State tax revenue than it exempted.

56

Data Source: Appendix N: Results of Economic and Revenue Impact Analyses.

NVTC 2020 Data Center Report

26

The appendix to the JLARC report shows that

• In 2017, the State took in $1.09 in state tax revenue from data center related activity for every

$1 of potential state tax revenue that was exempted from qualifying data centers.

• In 2016, the data center incentive was revenue neutral – it generated one dollar in additional

state tax revenue for every dollar of potential state tax revenue that it exempted.

• In every year since the data center incentive was modified in 2012, the State recovered the

majority of the state tax revenue that was exempted from qualifying data centers.

• From 2013 through 2017, on average the State recovered 75 cents in state tax revenue for every

dollar of potential tax revenue exempted from qualifying data centers.

57

Virginia’s Incentive is One of the Most Restrictive

Virginia’s data center incentive is structured so that it is only available to data centers that bring a

certain minimum number of jobs and a minimum amount of investment to the state. In order to qualify,

a data center must invest at least $150 million and add 50 new jobs to the local economy paying 50

percent more than the average annual wage in the locality (only 25 new jobs are required in

unemployment distressed localities). These restrictions incentivize data center companies to make

sizable investments in property and employment in the state.

Virginia’s data center incentive is very stringent in terms of the number of new jobs required to qualify

for it. Of the 31 states that actively offer data center incentives, only 11 require a minimum number of

new jobs to qualify for an incentive, and only Virginia, Mississippi, and Nevada require the creation of 50

or more new jobs. In terms of the minimum amount of investment required to qualify for an incentive,

Virginia’s incentive is more restrictive than most other states. Only seven states (Alabama, Georgia,

Illinois, Iowa, Nebraska, Oregon, and Texas) require a higher amount of investment in order to receive

the state’s most attractive incentive (and Alabama, Georgia, Iowa, Nebraska, and Texas all have

graduated incentive criteria, so that lesser investments may still qualify for incentives). At the same

time, 16 states offer their most attractive incentive to data center investments that are half as large as

the amount that Virginia requires to qualify for its incentive.

57

The JLARC report states that the data center incentive recovered 72 cents in state tax revenue for every dollar of potential tax

revenue exempted from qualifying data centers. That conclusion is based on including the years 2010 through 2012, prior to

the significant change made to the incentive in 2012. The 75-cent estimate more accurately reflects current state policy.

NVTC 2020 Data Center Report

27

Figure 6 shows how the investment and job creation criteria in different states compare. The closer a

state is to the lower-left corner of the graph, the less restrictive are the criteria to qualify for the state’s

most attractive incentive.

Figure 6. Minimum Investment and Job Creation Criteria for State Data Center Incentives

58

JLARC’s Primary Recommendation

In its evaluation, JLARC made some administrative and exploratory recommendations regarding the

State’s data center incentive. Its primary recommendation was for the General Assembly to consider

“reduc[ing] or remov[ing] the minimum job creation requirement of the sales and use tax exemption for

data centers locating in a distressed area or an enterprise zone.”

59

JLARC suggested that a lower job

creation threshold could encourage more data center growth in rural areas, based on its discussions

with data center industry representatives.

Because of reduced availability and rising prices of land in Northern Virginia, data centers are likely to

seek lower cost locations elsewhere in Virginia or outside of the state. Virginia has the opportunity to

58

A list and brief description of state incentives is located in the separate accompanying Appendix.

59

Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission, Data Center and Manufacturing Incentives, Economic Development Incentives

Evaluation Series. June 17, 2019.

MI, NM, NY, OK, UT, WA, WV, WI

MN

AZ, PA, WY

NC

KY, OH

FL, IN, MT

IA, OR

GA

MO, ND

TN

IL

AL

SC

NE

TX

MS

NV

VA

$0

$100

$200

$300

$400

$500

$600

0 10 20 30 40 50 60

Minimum New Investment (millions)

Minimum New Jobs

Qualification Criteria for Most Attractive Incentive

NVTC 2020 Data Center Report

28

continue to attract data centers to lower cost locations within the state, if the incentive requirements

stay competitive. However, the 50-job requirement is hard to meet for data centers that are not larger

than $300 million in capital investment. JLARC found that “one job is generally associated with $6.3

million in capital investment. Thus, a $150 million investment would be expected to create 24 jobs, on

average.”

60

As shown in Figure 9, Virginia, Mississippi, and Nevada are the only states that have a 50-job

requirement to receive the most attractive incentive.

Areas of Virginia that are relatively more distressed could benefit significantly from data centers which

are important sources of tax revenue, but which do not require substantial, costly local government

services. However, according to JLARC, generally, distressed regions do not already have the skilled

workforce in place that is necessary for data center operation, and it is often difficult to relocate

workers from other locations. According to JLARC, “Savings from the exemption can provide resources

to address these challenges.”

61

JLARC concluded that “The best approach at this time may be to reduce or remove the minimum job

creation threshold in distressed areas and enterprise zones … to encourage data center growth in these

areas.”

62

Incentives have been Instrumental in the Development of Virginia’s High-Tech

Infrastructure

The way that the high-tech industry has developed in Virginia is instructive as to the value of the data

center incentive. The earliest data centers began to cluster around Ashburn, Virginia at the dawn of the

internet because that was one of the four original network access points serving the entire country. In

2010, Microsoft began building its data center in Mecklenburg County after Virginia had enacted its

initial data center incentive bill. However, the growing industry did not begin to boom until after the

General Assembly strengthened and expanded Virginia’s data center tax incentive in 2012. The fiber

installed to support the large data center investments in Northern Virginia and Southern Virginia

allowed for a dramatic expansion of the industry in Virginia. As a result, Northern Virginia overtook the

New York City area in 2015 as the world’s largest data center market.

This expansion provided the impetus for Microsoft and Facebook to invest in bringing the MAREA

subsea cable to Virginia Beach, instead of only relying on the transatlantic cables that land in the New

York City area. Simultaneously, Telxius invested in the BRUSA cable connecting Virginia Beach to Puerto

Rico and Brazil. The cable landing station in Virginia Beach has attracted the Globalinx, NextVN, and

PointOne data centers to Virginia Beach. Virginia is recognized worldwide for its high-tech physical

60

Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission, Data Center and Manufacturing Incentives, Economic Development Incentives

Evaluation Series. June 17, 2019.

61

Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission, Data Center and Manufacturing Incentives, Economic Development Incentives

Evaluation Series. June 17, 2019.

62

Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission, Data Center and Manufacturing Incentives, Economic Development Incentives

Evaluation Series. June 17, 2019.

NVTC 2020 Data Center Report

29

infrastructure (conventional and renewable electric power facilities, terrestrial and subsea fiber

networks, and data centers) as well as for its high-tech workforce.

The DP Facilities data center that opened in Wise County in 2017 takes advantage of the MidAtlantic

Broadband Communities Corporation fiber connections to the MAREA subsea cable. The data centers in

Northern Virginia and the cable landing station in Virginia Beach attracted Facebook to invest in its large

data center in Henrico County, midway between the two locations. Additionally, QTS has connected its

large data center and network access point in Henrico County to the subsea cables in Virginia Beach,

offering very low latency connections to Europe and Brazil. Google is in the process of bringing its

DUNANT cable from northern Europe to Virginia Beach, and SAEx International has planned a global

cable system that will eventually connect Virginia Beach to Brazil, South Africa, India, and Singapore.

This system will provide a digital global superhighway, providing a unique four-continent link from Asia

to the Americas through Africa and creating a secure new submarine link that is able to avoid all the

common choke and risk points, such as the current network route through the Mediterranean and Red

Seas and the routes that are exposed to the seismic risks that exist in the Pacific Ring of Fire.

Data centers also are important for attracting other businesses to Virginia. For example, biotech firms

are extremely dependent on the storage and computing capacity of data centers for healthcare

innovations. This summer, after an extensive search, the biotech firm, Aperiomics chose Loudoun

County for its permanent corporate headquarters. Aperiomics is the only firm able to identify every

known bacterium, virus, fungus, and parasite. The company has created a new gold standard in

identifying the root cause of infectious diseases, allowing doctors to prescribe precise treatments for

specific infections. Aperiomics specifically identified the nearby access to data centers as one of the

reasons that it chose Loudoun County. “With its growing reputation as a major technology hub, access

to major data centers that allow us to maximize our Artificial Intelligence and genomic research and

quick access to major healthcare hubs across the East Coast, we cannot imagine a better place to call

home.”

63

The Virginia data center tax incentive sends a clear signal to potential investors worldwide that the

business climate in Virginia is friendly to the high-tech industry. Beyond reputation, the incentive

supports the investment in data centers, in conventional and renewable energy, in a robust fiber

network, and in a high-tech workforce.

The Incentive Helps to Attract Some Data Centers that Do Not Qualify for the Incentive

Data centers tend to cluster, with smaller data centers often locating adjacent to larger data centers.

Therefore, one data center that is attracted by the incentive can attract other data centers to take

advantage of the then existing local fiber and power infrastructure.

64

Some of these follow-on data

centers will be smaller than the larger data center projects that qualified for the tax incentive and may,

63

https://biz.loudoun.gov/2019/05/30/aperiomics-headquarters/

64

https://www.datacenterknowledge.com/industry-perspectives/finding-strength-numbers-data-center-clustering-effect

NVTC 2020 Data Center Report

30

themselves, not initially achieve the investment and job creation thresholds required to receive tax

benefit from the state.

Because large data centers that qualify for Virginia’s incentive help provide the infrastructure and

technology supply chain to attract smaller data centers that do not initially qualify for the incentive, the

incentive yields more data center investment than is measured by just counting the data centers that

qualify for the incentive. Virginia’s data center tax incentive plays an important role in attracting new

data centers to the state and in keeping them from moving to other states.

LOCAL INCENTIVES

Spurred by data center development in Northern Virginia, the growing importance of Virginia Beach as a