MEMORIES

Training, Sherpas and Friends - 1964

Travel to Darjeeling

It seems like ages ago. Yes, I went there for my Basic Course in Mountaineering, in

1964! It was course no.43, I think. If you know the history of HMI (Himalayan

Mountaineering Institute), this was the beginning decade. The courses then were for

35 days, plus almost eight days for travel to and fro Mumbai. We spent the first five

and the last three days at Darjeeling. Ten days to walk to base camp and ten for

training at the Base Camp and eight days to walk back. It was training at its best.

These long marches and the stay at the Base allowed us to interact with the great

Sherpas who accompanied us, including Tensing. We could enjoy the mountains and

immerse ourselves with understanding the area very well. A very sensible thing.

During the sixties and before, travel to Darjeeling itself was long and tedious. HMI was

authorized to offer a special Railway concession to students and that allowed me to

travel 1

st

class at half rate.

1

Mumbai to Kolkata by 1Dn Kolkata Mail via Nagpur was a

memorable experience with its views, rhythm and the Dinning Car, which has now

been discontinued. I changed to the Darjeeling Mail at Kolkata. Early next morning,

the train halted at Sahib Ganj, which was on the banks of the Ganga. In those days,

the railway bridge on the river was yet to be constructed. All the passengers and the

luggage had to be transported to the train waiting on the other side. Porters started

arriving and all the luggage was carried to the waiting steamer and was loaded into

the ferry, and many local cars too were being ferried. Thanks to my upper-class ticket,

I sat on the upper deck restaurant and enjoyed a breakfast, while the ferry made its

way across the Ganga over the next two hours.

The same scene repeated itself at Manihari Ghat, on the opposite North Bank. As we

embarked onto the train at the other side, we realised that it was an almost replica of

the train by which we had arrived, only it was now “Meter Gauge”. It was late in the

afternoon, and we were on the move again. It was astonishing to think that all the

British officers, administrators and the early Everest Expeditions travelling to

Darjeeling, had to go through this procedure. After a long sea voyage to Mumbai, it

was probably a test of endurance.

From Siliguri you had to catch a narrow-gauge train to Darjeeling. Comprising of about

15 bogies being pulled and pushed by three engines, this indeed was a remarkable

experience. After chugging along for two hours in the plains, the train is divided into

three sections of five bogies each, with one engine each. Two great engineering

marvels were designed in this system to help the engines haul up the train. First is a

climb up a very steep slope with each train going up on the slope. Then they would

1

All British officers always travelled First Class. As F. M. Bailey put it- “I had never travelled Second

Class in India, not even speculated what it was like. First-class travel was not merely the officer’s

prerogative. It was his duty to the British Raj.” No Passport to Tibet, by F. M. Baily, p.271. (The Travel

Book Club, London, 1957)

reverse back to be able to climb up higher. This way all the bogies were hauled up.

Later at Batasia Loop, the train would make the climb in rounds, one section going

over the other. This exists today too.

2

At the Darjeeling Railway station, two Sherpas with large badges of HMI, were

awaiting the arrival of the new students. A very grand gesture, I felt. We walked to

Jawaher Parvat, about 3 km away. Soon, we were settled at the Student’s Hostel.

3

Of the 30 students in my course, we were just two civilians- myself and Dilip Bhide

from Mumbai. There were 28 young army Lieutenants or Captains as other students.

But we were immediately welcomed by these young officers- as we were almost of the

same age. I was teamed with Col. Prem Chand of Gorkhas (not of Kangchenjunga

fame, but from the 11 Gorkhas). We became instant friends and shared many things

and remained friends until he died in 2011. There were differences in our physical

fitness and abilities, but we were not too far behind either. I was glad I had come well

prepared with many historic facts about that area, as I realised that some of the

Sherpas, including the great Tensing were keen to know more about the history of

their area.

Our course began the next day. The first thing was getting used to the stuff. Morning

running, PT (physical training) as per army style, some lectures on various subjects

and a movie on the Institute and training. After the day’s events, we all went off to the

Bazar, food at the Glenery’s, ice-cream and milk shakes at Kelvintor’s and books at

the Oxford Book Shop. All these establishments are still there. Five days flew by in an

instant. There was a cricket Test Match going on and as I had a radio, I was in great

demand. To my regret, three of the best amongst Sherpas, Nawang Gombu, Lhatoo

Dorjee and Ang Kami were joining the “Pre-Everest expedition to Rathong peak”.

Indian teams had attempted Everest twice before and 1965 was considered almost

the last chance for them to achieve the ascent. So, instead of the usual Advance

Course, which was generally held on same dates as the Basic course, HMI dedicated

this period to the selection of future Indian Everesters. In a way we were lucky, as we

were interacting with the future legends and were witnessing the senior-most

mountaineers of the country in action. Our instructors consisted of Tensing, Miken

Gyalzen, Sirdar Khamsang Wangdi (or simply Ongdi K.), Ang Temba, and Da

Namgyal -each a great man in his own way- worth a story each.

All these Sherpas had been to Everest on various expeditions- that was their bread

and butter and fame. But they had done other climbs too. Apart from Tensing, two of

the most senior Sherpas were with us, Gyalzen Mikchen, the Senior Instructor of the

course, had climbed with the Japanese, is credited with the first ascent of Pyramid

peak in 1949 and the first ascent of the difficult Manaslu peak in 1954.

Da Namgyal was part of the Sherpa group that carried heavy loads to South Col in

1953. Next day, he with Lord John Hunt carried loads to Camp VII on the southeast

2

Darjeeling Hill Railway. Many references on web.

3

The memories came back as I visited the area again - HMI and trek to Dzongri in 2020 - almost fifty-

five years after doing the course. Many things had changed of course. For starters, we flew from Mumbai

to Bagdogra (near Siliguri) in two hours and were in Darjeeling in the next two.

ridge, the final camp, and that helped Hillary and Tensing make the historic first ascent

of Everest two days later.

Tensing Norgay is of course renowned and there are several books on him. The first

Prime Minister of India, Nehru told him to “Produce a thousand Tensings for India”. To

that end the HMI was established with Tensing as Director of Field Training, a post he

held until he retired. Upon his death, he was cremated in the grounds above the HMI,

his statue stands there today. His soul certainly rests at HMI.

On the same grounds above HMI, was a lovely 19

th

Century memorial built in

memory of Diri Dolma, wife of Forest Ranger Kanta. It was demolished to build a

grotesque building to house a museum. It was an irreparable loss. So much for

those who care about history!

All other Sherpas were not so lucky as Tensing. Many years later, while visiting

Darjeeling, I saw the great Gyalzen and Da Namgyal Sherpas selling woollens to

tourists in the streets of Darjeeling to make ends meet. They had families to stay with,

and were doing this to supplement their daily expenses.

They were the senior most Sherpas and after decades of service at HMI, were the first

to retire. As per government classifications, they were not entitled to any pension. They

were celebrities in their own right, and I was shocked and disturbed to see them

reduced to such a pitiable condition. The Japanese and the British, with whom they

had much success, immediately offered help. But they thought it was best to fight for

their rights and to bring awareness to the situation for the benefit of both themselves

and their community and decided to demand for official pension instead of living off

voluntary support and assistance. The Government, like in all such cases, was

adamant and the rules were not changed.

I was with erudite Sherpa Dorjee Lhatoo, the then Deputy Director of Field Training at

HMI. We took a picture of Lhatoo in the bazaar, posing between these two great men,

selling woollens. The photo was captioned; “Two sweater sellers of Darjeeling and one

future sweater seller of Darjeeling”! It was circulated widely, especially in foreign

journals and magazines, causing much pressure on authorities. It had the desired

impact on Indian bureaucracy and rightful pension for the staff of HMI was introduced.

Our course started with Principal Col. Jaswal, delivering a welcome lecture. “You will

have a great experience, the mountains you will see and the great personalities you

will trek with, will be a delight. The base camp at Chaurikiang will be your home for

almost two weeks”. Some us chuckled at this Sikkimese name. “You can laugh now,

but I assure you this name you will remember all your life”. Five days were spent at

Darjeeling, starting with daily morning exercises and a run to the bazar followed by

various activities like issuing of equipment, lectures on medical aspects, safety and

getting to know our Sherpa Instructors. During one lecture, I was caught listening to a

radio, as there was a cricket Test match on. Luckily the speaker, a doctor, was also a

cricket fan and we exchanged the score!

In the hills near Mumbai, every December/January rock climbing training courses were

conducted. Sherpa instructors from Darjeeling, as they were free from routine courses,

used to come to Mumbai to teach. I had done a course there and hence knew some

of the Sherpas. All were seniors but very easy to get on with. So, sometimes I took

some liberties to joke with them and our army friends with their discipline would enjoy

that.

After five hectic days, the time came to start from Darjeeling. The Pre-Everest team

had already left. We started on our 10-day trek to the base camp, with heavy luggage

on our backs, to Singla Bazar, way down from Darjeeling on the banks of the Teesta

river, from where we enter Sikkim. Next day, on a cold October morning, we were

asked to jump into the river for a bath. I was aghast and caught hold of one of the

instructors known to me, begged to be excused. “I am from Mumbai and we never take

a bath in such cold water. If I am forced to, I will be sick for rest of the course.” Then I

added in jest “I am the only son of my father so why send me home sick!” They all

laughed and I was excused, but I am sure I was noted as a weakling.

We settled down to a routine of trekking. We were soon at Yoksum where a day was

spent acclimatising. That evening many pots of the famous drink of Sikkim “Tomba”

were brought, one for each of us. It is made of fermented barley in a bamboo container,

on which hot water is poured. You seep this mildly alcoholic drink slowly, and more

hot water is added no sooner you finish. It was a gift from the Sikkim government to

popularise their national drink! How successful was their ploy: till date, I ask for tomba

no sooner I am in those parts and I am sure my army friends, as they advanced in

ranks, have made their entire battalion drink it!

From Yoksum, the climb started. We went up on a steep terrain to Sachen, Bakkhim,

Tsoka to Phedang in particular, the last climb was very steep and many of us found it

challenging. But our army friends rose to the occasion, encouraging us and even

sharing some of the loads of others. I was later told that people have died out of

exhaustion or have had a heart attack on that section.

The next major camp was at Dzongri. No place in the Himalaya could be better I

thought. Rhododendrons, grassy meadows with some yak herders, Kangchenjunga

and other peaks rising all around. An extra day was spent here to acclimatise before

we walked the last section to Chaurikiang. As we pitched our tents, I said to myself

that the Principal was right- this is a place I will never forget in my life. Many giant

peaks of the Sikkim Himalaya were surrounding the vista. The camp situated in a bowl,

was next to a glacier. We were settled here for 10 days of training.

I remember Tensing, visiting our tents every morning and anyone who was not yet up

getting a shout. Even if someone was ill, there was no excuse- he would almost pull

down the tent and ask them to re-pitch it as an exercise to get fit. We were divided into

smaller groups of six each, called a “Rope”, with one Sherpa instructor in charge, for

better training. I was in the rope led by Sherpa Sirdar Wangdi, someone almost as

senior as Tensing. Daily we would line up for a short lecture by Tensing and then went

with our Rope Instructor. Rock climbing, ice and snow work, rappelling, crampon

climbing, use of ropes and rescue work - all other mountain activities were taught to

us. Due to these expert instructors, smaller group size and sufficient time, we had the

best of the training.

Sirdar Wangdi, my rope instructor, was a very different class of Sherpa. Educated and

well trained abroad, he knew his ropes well and was a good teacher. He was “Sirdar”

(leader of Sherpa team) of several expeditions in Nepal, and he received this

honourable nick name.

4

He was on International Women’s Expedition in 1959, led by

4

Sirdar Wangdi, born in 1932, first broke in on the Himalayan mountaineering scene with Raymond

Lambert on Cho Oyu in 1954. Since then Wangdi has mostly been associated with the French

mountaineers. Makalu with Franco in 1955, Trisul in 1956 with Franco again and Jannu in 1959, yet

again with Franco. He was awarded the Himalayan Club Tiger Badge and he became an Instructor at

Madam Cloude Kogan. The team had three Sherpanis, daughters of Tensing: Pem

Pem and Nima and his niece Doma from Darjeeling, thus establishing his future

connection with HMI. In an avalanche, Kogan, Claudine van der Straten-

Ponthozone and Wangdi were trapped in an avalanche. Kogan and Claudine died,

buried in the snow, but after almost three hours of struggle on his own, Wangdi came

out of the debris and survived.

5

His crowning glory was as Sirdar of the 1962 French expedition to Jannu

(Kumbhakarna) with Lionell Terray. He was one of the summiteers on one of the most

challenging mountains. On the summit, “Wangdi got a big Indian flag out of his bag,

then Nepalese and finally the colours of H M I.”, wrote Terray.

6

We remained in contact for many years after the course. He was well ahead of his

times. There were no trekking agencies in the 1960s and he thought of starting a

“Sherpa Guide School”. Not all Sherpas in Darjeeling were earning all the time, except

when they went on some expeditions in a year, if lucky. Wangdi managed to arrange

a group of six Sherpas, experts, but less employed. He agreed to give them a monthly

payment plus extra when climbing. This group settled at Manali, far away in the

western Himalaya. As Wangdi had married a girl from Kathmandu, he could manage

funds and much of the equipment. Soon, his agency became known and some groups

started using them.

Unfortunately, it created a lot of jealousy amongst the local babus. The mountaineering

Institute at Manali did not appreciate his presence as it was thought that he was

encroaching upon their territory. In 1967, I sent a large group of students from the

University of Mumbai to train under Wangdi. His Sherpas went off to a glacier far away to

train them. At the same time, an Indo-British team was climbing Mukarbeh, a challenging

peak, supported by Wangdi’s company. They were caught in a storm and called for rescue.

Wangdi went to the Institute for help, and to arrange a helicopter. He was denied any help

even in this emergency. Finally, he recalled one of his Sherpas and a student, Zerksis

Boga from the training camp immediately, and they went ahead with the rescue.

Unfortunately, three climbers, Geoff Hill, Suresh Kumar and Sherpa Pemba were found

dead, suffocated in their tents.7 This was picked by local administrators and politicians to

ruin Wangdi, with many inquiries and notices. In later years he himself accompanied a few

expeditions in the Kulu area, organised and built a Ski Hut on the slopes of Khanpari Tibba

but was uniformly unfortunate in his commercial ventures.

Business suffered, so did his health, and he took to heavy drinking. On one of my later

visits, I walked with him to the Mission Hospital in town. Walking small distances too was

a challenge and he had to rest often. The doctor gave a verdict that he had TB, and if he

would not stop drinking and smoking, he would not survive. Soon, thereafter he passed

away.

the Himalayan Mountaineering Institute. Wangdi was quiet, gentle self, looking rather frail, but terribly

wiry and tenacious in purpose. He was more intellectual than other Sherpas and his independent

spirit burnt fiercely inside him. (Soli Mehta, Himalayan Journal vol xiii, (1973-74)p . 226)

5

See book Sherpas, by Capt. M.S. Kohli, p. 47 (UBS Publishers and Distributors. New Delhi, 2003)

6

At Grips with Jannu by Jean Franco and Lionell Terray, p. 191. (Victor Gollancz Limited, London,

1967)

7

See “Mukar Beh 1968,” by John Ashburner, H.J. 28, p. 21. Details of accident and death on the

peaks in 1967 on p.22. Full details in “Alpine Journal, 1967” p. 315

Campfire

Soon, our days of training were over and the return trek started. In three days, we

were at the meadows of Yoksum. The same night, the Pre-Everest team also reached

there, full of spirits as they had climbed Rathong, a first ascent. To add to the pleasure,

Tensing had arranged permission to invite his friend Raymond Lambert, the famous

Swiss climber and his wife to join us. Ordinarily, foreigners were not permitted to visit

Sikkim, but Tensing was no ordinary person either.

Prem Chand my tent partner, was an officer from Army intelligence. “Harish, I see a

large box of Whisky in the luggage of Mr Lambert. We should manage to get some

bottles”. Being army officers, he and others could not ask for it, so the task fell on me,

a civilian. I chatted with Lambert as I knew something about his Everest record. Slowly,

I broached the subject. “Sir, we are all tired, can I request you to share a little whisky

with us?”

Lambert laughed and said “Ok if you give me a damn good campfire, I will consider it”.

That was no problem- we had students from every part of the country. Prem Chand

organised wood and lamb which was skinned and hung above the roaring fire to roast.

We started songs, skits, and stories from different regions. After half an hour Lambert

signalled to me to come and offered a couple of bottles of Whisky! With more Tomba

supplementing, the party took off. The senior team presented a Punjabi Bhangra, we

had an Assamese dance, someone sang a serious Bengali song and a south Indian

presented a classical piece. I presented a Gujarati Garba where you go round and

round in a large circle, in tune with a song with special delicate steps. Neither could I

sing nor the strong army officers take delicate steps- it was the funniest Garba dance

one could ever see.

Soon, Tensing got up and with a group of Sherpas went into the traditional Sherpa

dance, rhythm and grace personified. It was unique to see these senior Sherpas

dance, and one thought they could dance only on summits! Ang Kami Sherpa, who

became the youngest person to summit Everest next year (1965), came out with a

colourful scarf and performed a solo dance with Sherpanis singing songs. These were

performances to treasure. As the fire turned to embers and the party was suitably

drunk, Dorjee Lhatoo, came with a guitar and started singing as only he could. We all

gathered around him. The forest, cold Sikkim air, embers, moon and the singing were

a cocktail to sip on for hours.

It was time to return to Darjeeling. In a couple of days, we were again at Singla Bazar.

The last climb to Darjeeling was planned as a night-walk. Porters carrying lanterns,

some of us with torches and the heavy breathing of all of us in silence of the night,

was something to experience.

8

Next evening, the selection of team for the 1965 Everest was announced to great joy

for many and some disappointment for others. Capt. Mohan Kohli, was elected the

leader of the team, and there were celebrations and we juniors also joined in. The fun,

frolic and midnight drunken brawls are difficult to describe!

8

After my 2020 trek on the route to and back from Dzongri, I asked Dorjee Lhatoo about how many

times he has done this trek. “More than 100 times”, he replied casually and without any hesitation.

Like for every Basic Course a ‘Graduation Ceremony’ was held. This time Mr. S. S.

Khera and Mr. H C Sarin, both Presidents of the Indian Mountaineering Foundation,

were chief guests and awarded us the “Ice-axe badge” as memento for completing the

course. 35 days had flown by and we never knew how quickly the course was over.

After a month, the Graduation certificate from HMI arrived by post. I had received a

“B” grade, as expected. In fact, except for two students, the entire course had received

a B grade. During those days, the grading was strict but honourable, as we were

allowed to undertake an Advance Course of training with this grade. Next year, I went

on to the newly established Nehru Institute of Mountaineering to successfully complete

my advance training, the first advance course of the Institute. I remained friends with

most of the Sherpas and army officers.

9

I had my sweet revenge after about 40 years, in 2005. Having done much climbing

and exploration, I was invited to be the Chief Guest at the Graduation Ceremony at

HMI. After pinning ice-axe badges on students, I gave a short speech which went on

something like this: “You are at an important stage of your mountain training. Do not

worry about grades, just learn from the experience. Freedom of the Hills is something

you must enjoy. I am the most long lasting “B” grader from HMI, but you can imagine

the standard of training, that I still could do so much. On our course only two students

were A grade, and I do not know what happened to them! What you do after the

course, like “After Everest”, is important. You will remember this training, various

places, various names and cherish the new friends you have made, and it will be in

your memory- always.”

9

In 1970, after six years, then my fiancé Geeta went to HMI to undertake Basic course. She was

treated royally as Sherpas knew her relation with me and -she received an “A” grade as systems and

syllabus had been revised.

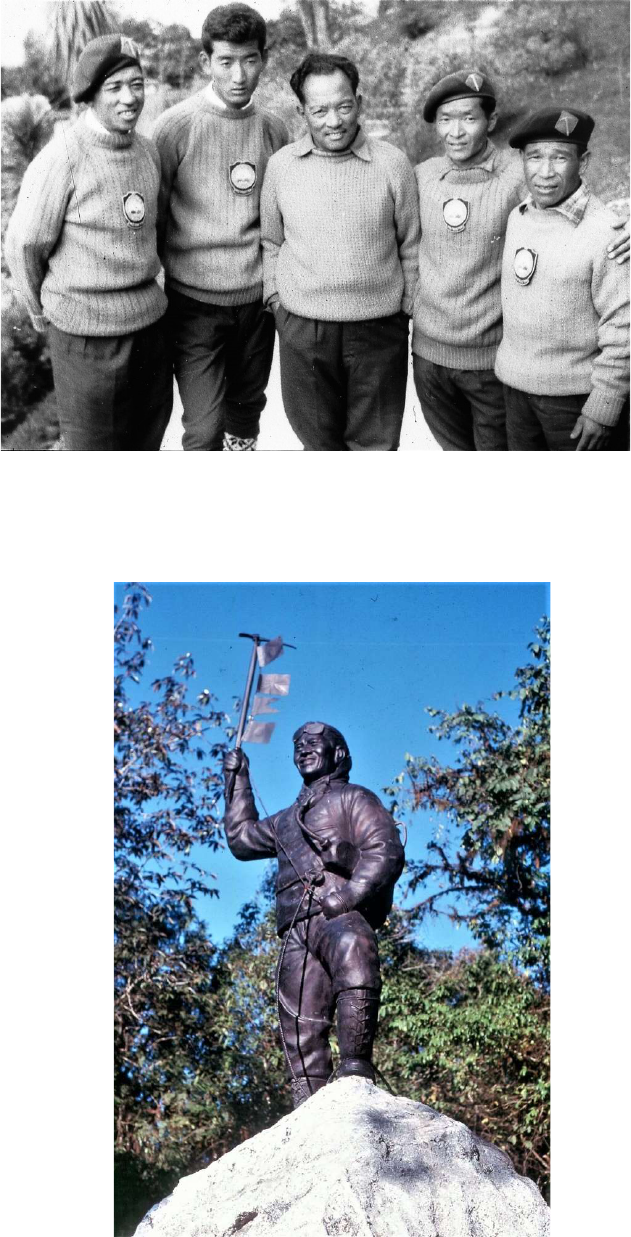

Memories- Photos

1. Early instructorsof HMI- (l to r) Da Namgyal, Phusumba, Gyalzen,

Wangdi and Ang Temba

2. Statue of Tensing Norgay above H M I

2. 19th Century memorial Chorten built in memory of Diri Dolma wife of Forest

Ranger Mr Kanta above HMI. It was demolished to build grotesque building

to house a museum

4. “Two eater sellers of Darjeeling and one future Sweater seller.” Gyalzen

(left) Lhatoo and Da Namgyal in bazaar of Darjeeling.

5 Wangdi on French expedition to Janu

6. Wangdi with group of Sherpas at Manali-SHERPA GUIDE SCHOOL-

Seating (l-r) Pasang Lakhpa, Dr S A (client), and Wangdi

7. Mr and Mrs Raymond Lambert at HMI, 1965 with Da Namgyal

8. Harish Kapadia receiving the graduation Ice Axe badge from S S Khera,

1964

9. Harish Kapadia, as Chief Guest at a Course graduation ceremony years

later.