Outcome Evaluation Strategies

for Domestic Violence Service Programs

Receiving FVPSA Funding

A Practical Guide

Written by

Eleanor Lyon, Ph.D.

Cris M. Sullivan, Ph.D.

Published by

National Resource Center

on Domestic Violence

6400 Flank Drive, Suite 1300

Harrisburg, PA 17112

November 2007

About the Authors

Dr. Eleanor Lyon is Director of the Institute for Violence Prevention and Reduction, and

Associate Professor in Residence at the School of Social Work at the University of Connecticut

(UConn). She has worked on issues related to violence against women as an advocate and

researcher since 1974. Before returning to UConn in 1998, Eleanor served as coordinator of a

domestic violence shelter program, followed by fifteen years as a researcher at a large community-

based social service / mental health agency.

Eleanor currently teaches classes on violence against women and research methods, in addition to

consulting and directing research and evaluation efforts. She specializes in evaluating programs for

battered women and their children, children who have been abused sexually, and interventions in

public schools; she has also conducted extensive research related to criminal sanctions policy. She

has received many federal, state and local grants to support this work. Among other efforts,

Eleanor helped to coordinate the “Documenting Our Work” project, served for eight years as

evaluator of VAWnet, and is currently the evaluation consultant for the National Center on

Domestic Violence, Trauma and Mental Health. Her most recent project is a national study of

domestic violence shelters. Among her publications is co-authorship of Safety Planning with

Battered Women.

Eleanor also conducts workshops on evaluation and issues related to violence against women. She

can be reached at eleanor.lyon@uconn.edu.

Dr. Cris M. Sullivan is a professor of Ecological/Community Psychology and associate chair of

the Psychology Department at Michigan State University (MSU). She has been an advocate and

researcher in the movement to end violence against women since 1982. In addition to her MSU

appointments, Cris is also the Director of Evaluation for the Michigan Coalition Against Domestic

and Sexual Violence and Senior Research Advisor to the National Resource Center on Domestic

Violence.

Cris’s areas of research expertise include developing and evaluating community interventions for

battered women and their children, improving the community response to violence against

women, and evaluating victim service programs. She has received numerous federal grants to

support her work over the years, including grants from the National Institute of Mental Health,

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the National Institute of Justice. Her most recent

project is a five-year NIMH RISP grant that involves collaborating with a large domestic abuse-

sexual assault victim service organization. The aim of this project is to enhance the organization’s

capacity to engage in collaborative research, and to build a strong partnership for conducting

meaningful and policy-oriented research on violence against women.

In addition to consulting for local, state, federal and international organizations and initiatives, Cris

also conducts workshops on (1) effectively advocating in the community for women with abusive

partners, and their children; (2) understanding the effects of domestic abuse on women and

children; (3) improving system responses to the problem of violence against women; and (3)

evaluating victim service agencies.

Cris can be reached at sulliv22@msu.edu and you can find out more about her work at

www.vaw.msu.edu/core_faculty/cris_sullivan.

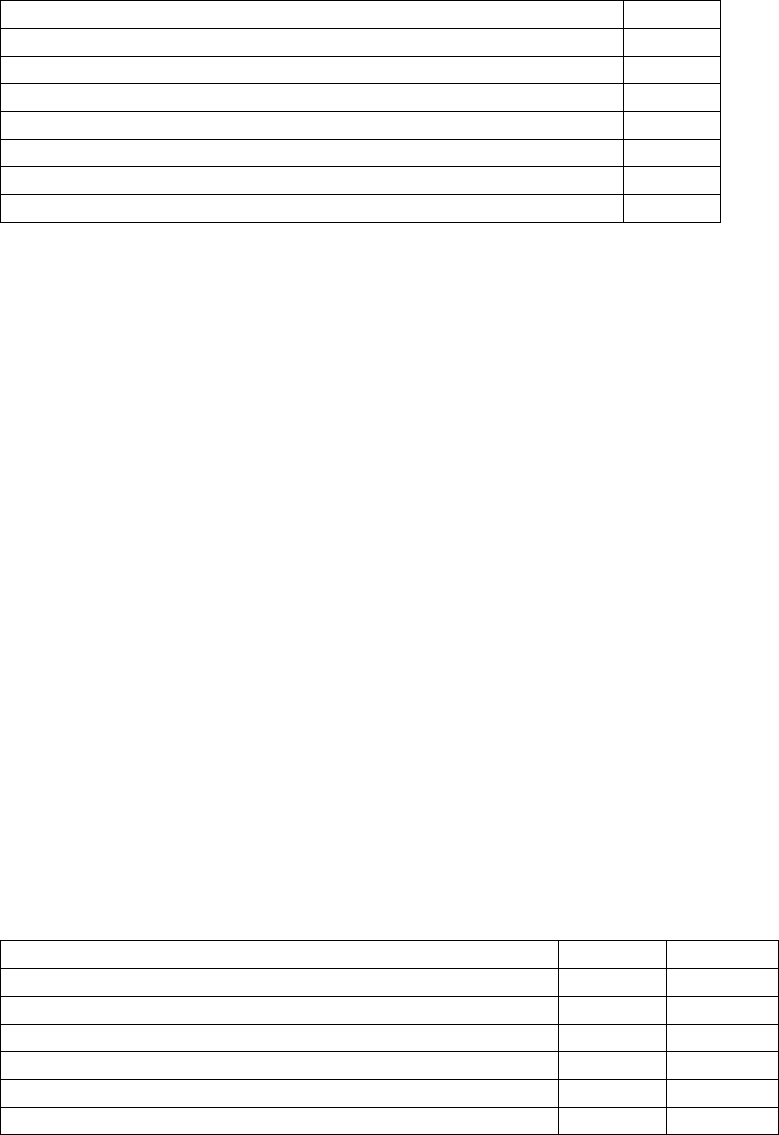

Table of Contents

Pages

BACKGROUND

A Brief History of the FVPSA Outcomes Project 1 - 4

A Word About Terminology 4

SECTION I: CONCEPTUAL ISSUES

Chapter 1: Why We Want to Evaluate Our Work

Why Many Domestic Violence Programs Resist Evaluation 5 - 7

Chapter 2: The Difference Between Research and Evaluation

The Difference Between Research and Evaluation 8 - 9

The Impact of Domestic Abuse Victim Services on Survivors’ Safety

and Well-Being: Research Findings to Date 9 - 12

Chapter 3: Important Considerations Before Designing

an Evaluation

Confidentiality and Safety of Survivors 13

Respecting Survivors Throughout the Process 13 - 14

Attending to Issues of Diversity 15 - 16

Chapter 4: A Brief Primer on the Difference Between

Process and Outcome Evaluation 17 -18

Chapter 5: Outcome Evaluation: What Effect Are We Having? 19

The Difference Between Objectives and Outcomes 20 - 21

Why We Caution Against Following Survivors Over Time as

Part of Outcome Evaluation 21 - 22

Choosing Outcomes that Make Sense to Our Programs 22 - 23

“Problematic” Outcome Statements to Avoid 23 - 25

The Hard-to-Measure Outcomes of Domestic Violence Programs 25 - 26

So, What is an Outcome Measure? 27

Chapter 6: The Documenting Our Work (DOW) Project

A Brief History of Documenting Our Work 28 - 30

Results of the DOW Pilot of Shelter Forms 30 - 34

Results of the DOW Pilot of Support Services and Advocacy Forms 34 - 36

Results of DOW Pilot of Support Group Forms 36 - 37

Chapter 7: The FVPSA Outcomes Pilot Project 38 - 43

SECTION II: PRACTICAL ISSUES

Chapter 8: Deciding How Much Information to Gather,

and When

General Guidelines for Using Samples 44 - 46

Special Considerations for Shelter Samples 46

Special Considerations for Support Group Samples 47

Special Considerations for Support Services and Advocacy Samples 48

Chapter 9: Collecting the Information (Data)

Designing a Protocol for Getting Completed Forms Back from Survivors 49 - 51

Creating a Plan With Staff for Collecting Outcome Evaluation Data 52

Collecting Information from Women in the Shelter 53 -54

Collecting Information from Support Clients 54

Collecting Information from Women Using Support Groups or

Group Counseling 55 - 56

Collecting Information from Survivors Participating in Individual

Counseling 56

Alternative Ways to Collect the Information 56 - 57

Chapter 10: Maintaining and Analyzing the Data

Storing the Data 58

Some Data Entry Considerations 59

How to Analyze the Information You Collect 59

Quantitative Information (including Frequencies and Cross tabs) 59 - 63

Qualitative Information 63 - 64

Points of Contact for Additional Information 64

Chapter 11: Sending the Findings to Your FVPSA Administrator 65 - 66

Chapter 12: Making Your Findings Work for You

Using Your Findings Internally 67

Using Your Findings Externally 67 - 68

How to Share Information with Others 69

When Your Findings are “Less than Positive” 70

Using Your Findings to Support the Continuation of Current Programs 70

Using Your Findings to Justify Creating New Programs 70 - 71

Important Points to Remember 71

APPENDICES

Appendix A: Sample Logic Models

Appendix B: The DOW Forms

Appendix C: FVPSA Pilot Project Feedback from Local Programs:

Verbatim Responses to Open-Ended Questions

Appendix D: Instructions for Using the Databases

Appendix E: Annual Report to Send to FVPSA Administrator

Appendix F: Glossary of Terms

Appendix G: Additional Readings

Appendix H: Literature Cited

FVPSA Outcomes Evaluation: A Practical Guide page 1

Outcome Evaluation Strategies

for Domestic Violence Service Programs

Receiving FVPSA Funding

A Practical Guide

The Family Violence Prevention and Services Administration (FVPSA) within the

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has been the major source of funding for

domestic violence coalitions and programs since 1984. In fiscal year 2007, FVPSA

provided almost $125 million to support the work of community-based domestic violence

programs, state coalitions, and a network of national resource centers. The overall purpose

of this FVPSA outcome evaluation project is to help states develop and implement

outcome evaluation strategies that will accurately capture the impact of FVPSA dollars on

survivors’ safety and wellbeing.

A Brief History of the FVPSA Outcomes Project

In 2005, the Office of Management of the Budget (OMB) reviewed the FVPSA

Program along with other federal grant programs within the Administration for Children

and Families at HHS. The review of the FVPSA program concluded that “results were not

adequately demonstrated.” In response to this finding, a national advisory group of FVPSA

administrators, state coalition directors, local domestic abuse program staff, tribal program

staff and evaluation specialists was convened to develop strategies for more effectively

demonstrating the impact of the FVPSA program.

It was not a simple task to create outcomes that would adequately reflect results

that might be desired across the different services being provided by domestic violence

programs (shelter, support groups, counseling, advocacy, etc.). However, the advisory

group examined evaluation work that had already been occurring in both Michigan and

Pennsylvania, and chose two outcomes that had been accepted by executive directors of

programs in those states and that captured two goals of any service being offered by

FVPSA Outcomes Evaluation: A Practical Guide page 2

domestic violence programs: to safety plan with survivors and to ensure that survivors are

aware of community resources they might need in the future. There was also research

supporting that these two short-term outcomes led to reduced violence and increased

quality of life for survivors over time. (See pages 9-12 of this manual for a summary of this

research.)

This led the advisory group to agree on the following two outcomes to be collected

from all FVPSA grantees by fall of 2008:

• As a result of contact with the domestic violence program, 65% or more of

domestic violence survivors will have strategies for enhancing their safety.

• As a result of contact with the domestic violence program, 65% or more of

survivors will have knowledge of available community resources.

The 65% target was based on programs’ experience and advisors’

recommendations. Although much of the work done by domestic violence programs

involves services related to safety planning and community resources, program staff do not

always have extensive contact with individual survivors, so not all of them would report

changes in these two areas. For this reason, “65% or more” was seen by advisors as a

realistic initial goal. Once programs have begun to collect this information from survivors,

the percentage goals will be changed to reflect figures based on actual data submitted.

Those percentages will then become the outcome goals for the FVPSA funded programs,

and included in the annual report to the Office of Management and Budget (OMB).

These two outcomes were also chosen because they relate not just to individual

level change (the survivor’s safety and well-being), but they also provide evidence,

important to more and more funders, of stronger and safer communities. Specifically,

research has demonstrated that increasing survivors’ knowledge of safety planning and of

community resources leads to increased safety and well-being over time (see Bybee &

Sullivan, 2002; Goodkind, Sullivan, & Bybee, 2004; Sullivan & Bybee, 1999). Since a good

deal of intimate partner abuse happens outside of the home in communities, such as the

workplace (McFarlane et al., 2000; U.S. Dept of Justice Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2001),

safer women means safer communities. Abuse can also have deleterious effects on

survivors’ ability to work and care for themselves and their children. Therefore, again,

improving women’s quality of life directly improves community well-being.

FVPSA Outcomes Evaluation: A Practical Guide page 3

After the national advisory group agreed upon the two outcomes, discussion

centered on how local programs could measure the extent to which those outcomes

occurred, without overburdening them more than necessary. Some of the advisory board

members were also participating in the national Documenting Our Work (DOW) Project,

and that project provided extremely helpful building blocks for the current effort. The

DOW Project had already developed tools that included measuring the two outcomes, and

advisory members discussed how these tools might be shared nationally to assist programs

with evaluating their work. A history of DOW and some of its pilot results are described in

Chapter 6.

The national advisory group was clear in its recommendation that requirements for

collecting and reporting on the two outcomes be phased in for programs, with adequate

training and technical assistance provided. It was suggested that a two-year pilot project be

implemented that would include working with states to determine the best ways to collect

and report these data. This handbook was created as one component of this effort, and is

intended to provide programs with practical strategies for conducting outcome evaluation.

While the manual focuses on collecting the two outcomes mandated for FVPSA

grantees, the strategies can also be used for all outcome evaluations being conducted by

domestic violence organizations. The intent is twofold:

♦ First, programs are feeling external pressure from funding sources to conduct

outcome evaluation, and it is our sincere hope and expectation that the information

gained through the methods in this guidebook will be useful in carrying out such

evaluations in a way that is not overly burdensome.

♦ Second, and more importantly, we hope and expect that the strategies outlined in

this manual will be helpful for programs to conduct evaluations that will be

meaningful to their work and that will lead to providing the most effective services

possible to survivors of domestic violence.

Most immediately, however, we have designed this manual to help programs collect the

two new outcomes for FVPSA grantees.

This manual is divided into three sections. The first focuses on conceptual issues to

consider before conducting an outcome evaluation, and ends with the description of

Documenting Our Work (DOW). The second section provides practical information about

data collection, analysis, interpretation, and presentation of findings. The third section (the

FVPSA Outcomes Evaluation: A Practical Guide page 4

Appendix) includes the actual DOW tools you might want to use, modify or shorten for

your evaluation work, as well as other background and supplemental material we hope

you find helpful.

A Word About The Terminology Used In The Manual

While all those being victimized by an intimate partner deserve effective advocacy,

protection, and support, the overwhelming majority of domestic violence survivors are

women battered by intimate male partners. For that reason, survivors are referred to as

"women" and "she/her" throughout this manual.

A conscious decision was also made to use the term "survivor" instead of "victim"

throughout this manual. Although there is debate about the use of these terms in the field,

the authors are more comfortable describing women, not in terms of their victimization,

but rather by their strengths, courage and resilience.

SECTION 1

CONCEPTUAL ISSUES

FVPSA Outcomes Evaluation: A Practical Guide page 5

Chapter One

Why We Want to Evaluate Our Work

Although the thought of "evaluation" can be daunting, if not downright

intimidating, there are some good reasons why we want to evaluate the job we are

doing. The most important reason, of course, is that we want to understand the impact

of what we are doing on women's lives. We want to build upon those efforts that are

helpful to women with abusive partners; at the same time, we don't want to continue

putting time and resources into efforts that are not helpful or important. Evaluation is

also important because it provides us with "hard evidence" to present to funders,

encouraging them to continue and increase our funding. Most of us would agree that

these are good reasons to examine the kind of job we're doing...BUT...we are still

hesitant to evaluate our programs for a number of reasons.

Why Many Domestic Violence Programs Resist Evaluation

(and reasons to reconsider!)

“Research has been used against women with abusive partners.” It is true that

people can manipulate or misinterpret research data. However, this is actually a

reason why we need to understand and conduct our own evaluations. To effectively

argue against the misinterpretation of other research, we must at least have a general

understanding of how data are collected, analyzed, and interpreted.

(related): “I don't trust researchers.” Too many programs have had bad

experiences with researchers who come into their settings, collect their data, and are

either never heard from again or who then interpret their findings without a basic

understanding of domestic violence issues. In the academic arena we refer to this as

"drive-by data collection," and we would strongly recommend programs turn such

researchers away at the door. But please remember that working with a researcher to

do program evaluation is optional. This handbook is designed to give you the basic

information you will need to conduct your own outcome evaluation.

FVPSA Outcomes Evaluation: A Practical Guide page 6

“Funders (or the public) will use our findings against us.” A common concern

we have heard from program staff is that our own evaluations could be used against

us because they might not "prove" we are effective in protecting women from

intimate violence. This fear usually comes from people who think that the funders

(or the public) expect us, on our own, to end intimate violence against women. We

would argue that it is unrealistic to expect victim service programs to end

victimization -- that is the role of perpetrator service programs as well as the larger

community. We do, however, need to know if we are effectively meeting goals that

are realistic.

"I have no training in evaluation!" That's why you're reading this manual. There

is a scary mystique around evaluation -- the idea that evaluation is something only

highly trained specialists can (or would want to!) understand. The truth is, this

manual will provide you with most, if not all, of the information you need to conduct

a program evaluation.

“We don't have the staff (or money) to do evaluation.” It is true that evaluating

our programs takes staff time and money. One of the ways we need to more

effectively advocate for ourselves is in educating our funding sources that evaluation

demands must come with dollars attached. However, this manual was created to

prevent every program from having to "re-invent the wheel." Hopefully the strategies

outlined in the following chapters will assist you in conducting evaluation without

having to devote more time and money than is necessary to this endeavor.

“Everyone knows you can make data say anything you want to, anyway.”

This actually isn't true. Although data are open to interpretation, such interpretation

has its limits. For example, if you ask survivors, out of context, how often they

slapped their assailants in the last year, and 78% reported they did so at least once,

you could try to make the argument that women are abusive toward men (which is

why it is so important to word questions accurately and ask contextual questions).

On the other hand, if you collected this same information and then claimed women

FVPSA Outcomes Evaluation: A Practical Guide page 7

never slapped their assailants under any circumstances, you would not have the data

to back you up. Data can be manipulated, but only so far. And the more you

understand research and evaluation the more easily you will be able to point out

when and how data are misinterpreted.

“We've already done evaluation [last year, 10 years ago]; we don't need to

do it again.” Things change. Programs change, and staff change. We should

continually strive to evaluate ourselves and improve our work.

*******************

Knowledge is power. And the more service providers and advocates know about

designing and conducting evaluation efforts the better those efforts will be. Evaluating

our work can provide us with valuable information we need to continually improve our

programs.

The next chapter provides a quick description of the distinction between research

and evaluation, and an overview of some of the knowledge we have gained to date from

recent research. As we will explain more fully in the next chapter, it can be helpful to

know what prior research has found about the effectiveness of services for battered

women, so that we can feel confident we are measuring the appropriate short-term

outcomes that will lead to desired long-term outcomes.

FVPSA Outcomes Evaluation: A Practical Guide page 8

Chapter Two

The Difference Between Research and Evaluation

Many people find the distinction between “research” and “evaluation” to be

confusing, but it’s really not complicated.

♦ Research is a broad term that refers to collecting information about a

topic in an organized, systematic way. It can answer many questions that are

interesting and useful to us, such as how widespread domestic violence is in a

particular country, or within a particular age group. It can answer simple

questions such as these (although getting credible answers might be difficult), or

much more complicated questions, such as “what are the primary factors that

contribute to women’s increased safety after an episode of abuse?”

♦ Evaluation is a particular kind of research. It answers questions about

programs or other kinds of efforts to provide services or create change in

some way. Again, the questions can be simple, such as “what did the program

do?” or more complex, such as “how was the program helpful, and for which

people?” Evaluation research, as the term suggests, tries to answer questions

about a program’s “value.”

Both research and evaluation can provide very useful information for domestic

violence programs. Research usually is conducted so that its results can be applied or

“generalized” to broad segments of the population, such as all women who call the

police after an abusive incident. Large evaluation studies may also be designed so that

they can be applied to many programs of a particular type, such as shelter programs.

Most credible research and large evaluations—especially the ones that follow

people over time, to determine long-term outcomes—can be complicated to conduct,

require substantial funding, and are likely to need help from people who have received

specialized training. Without extra resources they are probably beyond the capacity of

most local domestic violence programs to do on their own. Very good and helpful

FVPSA Outcomes Evaluation: A Practical Guide page 9

evaluations can also be done, however, by local programs, and without a huge financial

investment. That is what we hope this manual will help you to do.

Before we turn to more of the conceptual issues involved with your local

evaluation, however, we want to provide an overview of some of the useful results of

recent research and evaluation. Knowing about such results can suggest program ideas,

as well as ideas for questions you can ask about what your program is doing (or not

doing). Using these kinds of research and evaluation results is what is meant by

“evidence-based practice”—something that makes sense and is being urged more and

more frequently. It essentially means using the best scientific evidence you can find to

decide how to provide services or do other things to help people and communities

affected by domestic violence, and to prevent further violence from occurring.

The Impact of Domestic Abuse Victim Services on

Survivors’ Safety and Wellbeing: Research Findings to Date

It can be helpful to know what research studies have found about the

effectiveness of our efforts, so that we can feel confident we are measuring the

appropriate short-term outcomes that will lead to desired long-term outcomes for

survivors. Unfortunately very few studies to date have examined the long-term impact of

victim services on survivors over time. However, the studies that have been conducted

have consistently found such services to be helpful.

Shelter programs have been found to be one of the most supportive, effective

resources for women with abusive partners, according to the residents themselves

(Bennett et al., 2004; Bowker & Maurer, 1985; Gordon, 1996; Sedlak, 1988; Straus,

Gelles, & Steinmetz, 1980; Tutty, Weaver, & Rothery, 1999). For example, Berk,

Newton, and Berk (1986) reported that, for women who were actively attempting other

strategies at the same time, a stay at a shelter dramatically reduced the likelihood they

would be abused again.

One research study used a true experimental design and followed women for two

years in order to examine the effectiveness of a community-based advocacy program for

domestic abuse survivors. Advocates worked with women 4-6 hours a week over 10

FVPSA Outcomes Evaluation: A Practical Guide page 10

weeks, in the women’s homes and communities. Advocates were highly trained

volunteers who could help women across a variety of areas: education, employment,

housing, legal assistance, issues for children, transportation, and other issues. Women

who worked with the advocates experienced less violence over time, reported higher

quality of life and social support, and had less difficulty obtaining community resources

over time. One out of four (24%) of the women who worked with advocates experienced

no physical abuse, by the original assailant or by any new partners, across the two years

of post-intervention follow-up. Only 1 out of 10 (11%) women in the control group

remained completely free of violence during the same period. This low-cost, short-term

intervention using unpaid advocates appears to have been effective not only in reducing

women's risk of re-abuse, but in improving their overall quality of life (Sullivan, 2000;

Sullivan & Bybee, 1999).

Close examination of which short-term outcomes led to the desired long-term

outcome of safety found that women who had more social support and who reported

fewer difficulties obtaining community resources reported higher quality of life and less

abuse over time (Bybee & Sullivan, 2002). In short, then, there is evidence that if

programs improve survivors’ social support and access to resources, these serve as

protective factors that enhance their safety over time. While local programs are not in the

position to follow women over years to assess their safety, they can measure whether

they have increased women’s support networks and their knowledge about available

community resources.

The only evaluation of a legal advocacy program to date is Bell and Goodman’s

(2001) quasi-experimental study conducted in Washington, DC. Their research found

that women who had worked with advocates reported decreased abuse six weeks later,

as well as marginally higher emotional well-being compared to women who did not

work with advocates. Their qualitative findings also supported the use of

paraprofessional legal advocates. All of the women who had worked with advocates

talked about them as being very supportive and knowledgeable, while the women who

did not work with advocates mentioned wishing they had had that kind of support while

they were going through this difficult process. These findings are promising but given the

lack of a control group they should be interpreted with extreme caution.

FVPSA Outcomes Evaluation: A Practical Guide page 11

Another research study examined domestic abuse survivors’ safety planning

efforts (Goodkind, Sullivan, & Bybee, 2004). Survivors were asked what strategies they

had used to stop or prevent the abuser’s violence. For every strategy mentioned, women

were asked if it made the abuse better, worse, or had no effect. Not surprisingly, for

every strategy that made the situation better for one woman, the same strategy made the

situation worse for another. However, the two strategies that were most likely to make

the situation better were contacting a domestic violence program, and staying at a

domestic violence shelter. These results provide strong support for the importance of

domestic violence programs.

It is also important, though, that women who were experiencing the most

violence and whose assailants had engaged in the most behaviors considered to be

indicators of potential lethality were the most actively engaged in safety planning

activities, but remained in serious danger, despite trying everything they could. These

findings highlight the importance of remembering that survivors are not responsible for

whether or not they are abused again in the future. For some women, despite any safety

strategies they employ, the abuser will still choose to be violent.

Evaluations of support groups have unfortunately been quite limited. One notable

exception is Tutty, Bidgood, and Rothery’s (1993) evaluation of 12 “closed” support

groups (i.e., not open to new members once begun) for survivors. The 10-12 week,

closed support group is a common type of group offered to survivors, and typically

focuses on safety planning, offering mutual support and understanding, and discussion of

dynamics of abuse. Tutty et al.’s (1993) evaluation involved surveying 76 women before,

immediately after, and 6 months following the group. Significant improvements were

found in women’s self-esteem, sense of belonging, locus of control, and overall stress

over time; however, fewer than half of the original 76 women completed the 6-month

follow-up assessment (n = 32), and there was no control or comparison group for this

study. Hence, these findings, too, should be interpreted with extreme caution.

Tutty’s findings were corroborated by a more recent study that did include an

experimental design (Constantino, Kim, & Crane, 2005). This 8-week group was led by a

trained nurse and focused on helping women increase their social support networks and

access to community resources. At the end of the eight weeks the women who had

participated in the group showed greater improvement in psychological distress

FVPSA Outcomes Evaluation: A Practical Guide page 12

symptoms and reported higher feelings of social support. They also showed less health

care utilization than did the women who did not receive the intervention.

These research studies are presented to provide you with some evidence

supporting the long-term effectiveness of the types of services you offer. If programs can

show that they have had positive short-term impacts on women’s lives that have been

shown to lead to longer-term impacts on their safety and well-being, this should help

satisfy funders that the services being provided are worthwhile. The two outcomes that

will be required—help with safety planning and increased knowledge of community

resources—are clearly vital short-term outcomes that have been demonstrated to

contribute to improvements in longer-term safety and well-being. These are among the

short-term impacts that this manual will help you to measure.

FVPSA Outcomes Evaluation: A Practical Guide page 13

Chapter Three

Important Considerations Before

Designing any Evaluation

Before even beginning any evaluation efforts, all programs should consider three

important issues: (1) how you will protect the confidentiality and safety of the women

providing you information, (2) how to be respectful to women when gathering and using

information, and (3) how you will address issues of diversity in your evaluation plan.

Confidentiality and Safety of Survivors

The safety of the women with whom we work must always be our top priority.

The need to collect information to help us evaluate our programs must always be

considered in conjunction with the confidentiality and safety of the women and children

receiving our services. It is not ethical to gather information just for the sake of gathering

information; if we are going to ask women very personal questions about their lives,

there should always be an important reason to do so, and their safety should not be

compromised by their participation in our evaluation. The safety and confidentiality of

women must be kept in mind when (1) deciding what questions to ask; (2) collecting the

information; (3) storing the data; and (4) presenting the information to others.

Respecting Survivors Throughout the Process

When creating or choosing questions to ask women who use our services, we

must always ask ourselves whether we really need the information, how we will use it,

whether it is respectful or disrespectful to ask, and who else might be interested in the

answers. As an example, let's assume we are considering asking women a series of

questions about their use of alcohol or drugs. The first question to ask ourselves is:

How will this information be used? – To ensure women are receiving adequate services?

To prevent women from receiving services? Both? If this information is not directly

relevant to our outcome evaluation efforts, do we really need to ask?

FVPSA Outcomes Evaluation: A Practical Guide page 14

Second, how should we ask these questions in a respectful way? First and

foremost, women should always be told why we are asking the questions we're asking.

And whenever possible, an advisory group of women who have used our services should

assist in supervising the development of evaluation questions. The next question is: who

else might be interested in obtaining this information? Assailants' defense attorneys?

Child Protective Services? Women should always know what might happen to the

information they provide. If you have procedures to protect this information from others,

women should know that. If you might share this information with others, women need

to know that as well. Respect and honesty are key.

The words anonymous and confidential have different meanings.

Although many people incorrectly use them interchangeably, the distinction

between these two words is important.

Anonymous - you do not know who the responses came from. For example,

questionnaires without names or other traceable identifiers left in locked boxes

are anonymous.

Confidential - you do know (or can find out) who the responses came from, but

you are committed to keeping this information to yourself. A woman who

participates in a focus group is not anonymous, but she expects her responses to

be kept confidential.

Attending to Issues of Diversity

Most domestic violence service delivery programs are aware that they must meet

the needs of a diverse population of women, children, and men. This requires taking steps

to ensure our programs are culturally competent, as well as flexible enough to meet the

needs of a diverse clientele.

Cultural competence is more than just "expressing sensitivity or concern" for

individuals from all cultures (cultural sensitivity). A culturally competent program is one

that is designed to effectively meet the needs of individuals from diverse cultural

backgrounds and experiences. It involves understanding not only the societal oppressions

faced by various groups of people, but also respecting the strengths and assets inherent in

different communities. This understanding must then be reflected in program services,

staffing, and philosophies.

In addition to diversity in culture, there is a great deal of other variability among

the individuals needing domestic violence service delivery programs, including diversity

across:

♦ age

♦ citizenship status

♦ gender identity

♦ health (physical, emotional, and mental)

♦ language(s) spoken

♦ literacy

♦ physical ability and disability

♦ religious and spiritual beliefs

♦ sexual orientation

♦ socioeconomic status

Although process evaluation is commonly thought of as the best way to understand the

degree to which our programs meet the needs of women from diverse experiences and

cultures (see Chapter 3), outcome evaluation should also attend to issues of diversity.

FVPSA Outcomes Evaluation: A Practical Guide page 16

This handbook takes the position that outcome evaluation must be designed to answer

the question of whether or not women attained outcomes they identified as important to

them. So for example, before asking women if they obtained a protective order, you must

first ask if they wanted a protective order. Before asking if your support group decreased a

woman's isolation, you would want to know if she felt isolated before attending your

group. Not all women seek our services for the same reasons, and our services must be

flexible to meet those diverse needs. Outcome evaluation can inform you about the

different needs and experiences of women and children, and this information can be used

to inform your program as well as community efforts.

Attending to issues of diversity in your outcome evaluation strategies involves: (1)

including the views and opinions of women and children from diverse backgrounds and

experiences in all phases of your evaluation; (2) including "demographic" questions in your

measures (e.g., ethnicity, age, primary language, number of children, sexual orientation)

that will give you important information about respondents' background and situations;

and (3) pilot testing your outcome measures with individuals from diverse cultures,

backgrounds, and experiences.

FVPSA Outcomes Evaluation: A Practical Guide page 17

Chapter Four

A Brief Primer on the Difference Between

Process and Outcome Evaluation

Even though this handbook focuses primarily on outcome, not process, evaluation,

there is enough confusion about the difference between the two to warrant a brief

discussion of process evaluation. Process evaluation assesses the degree to which your

program is operating as intended. It answers the questions:

What (exactly) are we doing?

How are we doing it?

Who is receiving our services?

Who isn't receiving our services?

How satisfied are service recipients?

How satisfied are staff? Volunteers?

How are we changing?

How can we improve?

These are all important questions to answer, and process evaluation serves an

important and necessary function for program development. Examining how a program is

operating requires some creative strategies and methods, including interviews with staff,

volunteers, and service recipients, focus groups, behavioral observations, and looking at

program records. Some of these techniques are also used in outcome evaluation, and are

described later in this handbook.

When designing outcome measures, it is common to include a number of "process-

oriented" questions as well. This helps us determine the connection between program

services received and outcomes achieved. For example, you might find that women who

received three or more hours of face-to-face contact with your legal advocate were more

likely to report understanding their legal rights than were women who only talked with

your legal advocate once over the phone. Or you might discover that residents of your

shelter were more likely to find housing when a volunteer was available to provide them

with transportation.

FVPSA Outcomes Evaluation: A Practical Guide page 18

Process evaluation is also important because we want to assess not just whether a

woman received what she needed (outcome), but whether she felt "comfortable" with the

staff and volunteers, as well as with the services she received. For example, it is not

enough that a woman received the help she needed to obtain housing (outcome), if the

advocate helping her was condescending or insensitive (process). It is also unacceptable if

a woman felt "safe" while in the shelter (outcome) but found the facility so dirty (process)

she would never come back.

In summary…

♦ PROCESS EVALUATION helps us assess what we are doing, how we

are doing it, why we are doing it, who is receiving the services, how

much recipients are receiving, the degree to which staff, volunteers,

and recipients are satisfied, and how we might improve our programs.

♦ OUTCOMES EVALUATION assesses program impact – What

occurred as a result of the program? Outcomes, as we discuss in the

next chapter, must be measurable, realistic, and philosophically tied to

program activities.

FVPSA Outcomes Evaluation: A Practical Guide page 19

Chapter Five

Outcome Evaluation:

What Effect Are We Having?

It is extremely common for people to confuse process evaluation with outcome

evaluation. Although process evaluation is important -- and discussed in the previous

chapter -- it is not the same as outcome evaluation.

OUTCOME EVALUATION

assesses what occurred as a direct result of the program. Outcomes must be

measurable, realistic, and philosophically tied to program activities.

One of the first places many people get "stuck" in the evaluation process is with all of

the terminology involved.

Objectives

Goals

Outcomes

Outcome Measures

These terms have struck fear in the hearts of many, and are often the cause of

abandoning the idea of evaluation altogether. One reason for this is that the terms are not

used consistently by everyone. Some people see goals and objectives as interchangeable, for

example, while others view objectives and outcomes as the same. What is more important

than memorizing terminology is understanding the meaning behind the labels. This manual

will describe the concepts behind the terms so even if a specific funder or evaluator uses

different terminology than you do, you will still be able to talk with each other!

FVPSA Outcomes Evaluation: A Practical Guide page 20

The Difference Between Objectives and Outcomes

Effective evaluation begins by first defining our overarching goals (sometimes also

referred to as objectives). Goals or objectives (and we’re using these terms

interchangeably; not everyone does) are what we ultimately hope to accomplish through

the work we do. Program goals, usually described in our mission statements, are long-term

aims that are difficult to measure in a simple way.

We would say that the OVERALL GOAL OR OBJECTIVE of domestic violence

victim service programs is to –

enhance safety and justice

for battered women and their children

While it is not important that you agree with this overall objective, it is important

that you choose goals and objectives that make sense for your agency. After the program's

overall objective has been established, it is important to consider what we expect to see

happen as a result of our program, that is measurable, that would tell us we are meeting

our objective(s). These are program OUTCOMES.

The critical distinction between goals and outcomes is that outcomes are statements

reflecting measurable change due to your programs' efforts. Depending on the individual

program, PROGRAM OUTCOMES might include:

a survivor's immediate safety

the immediate safety of the survivor's children

a survivor's increased knowledge about domestic violence

a survivor's increased awareness of options

a survivor's decreased isolation

a community's improved response to battered women and their children

the public's increased knowledge about domestic violence

a perpetrator's cessation of violence (NOTE: only for programs that focus

specifically on the abuser)

FVPSA Outcomes Evaluation: A Practical Guide page 21

There are two types of outcome we can evaluate: long-term outcomes and short-

term outcomes. Long-term outcomes involve measuring what we would expect to

ultimately occur, such as:

increased survivor safety over time

reduced incidence of abuse in the community

reduced homicide in the community

improved quality of life of survivors

As we noted in Chapter 2, measuring long-term outcomes is very labor intensive,

time consuming, and costly. Research dollars are generally needed to adequately examine

these types of outcomes. More realistically, you will be measuring the short-term

outcomes that we expect to lead to the longer-term outcomes.

Why We Caution Against Following Survivors Over Time

as Part of Outcome Evaluation

Some funders are now asking grantees to follow their clients over time (sometimes

for as long as six months or a year) to obtain longer-term outcome data. While we

understand the desire for such data, this again is where we must differentiate between the

roles and capabilities of service programs and researchers. Safely tracking, locating, and

interviewing survivors over time is extremely costly, time-consuming, and resource-

intensive to do correctly. And we have yet to hear of a case where the funder mandating

this new activity is also providing additional money to pay for this additional work.

In the study mentioned in Chapter 3 that involved interviewing survivors every six

months over two years, the investigators were able to successfully locate and interview

94% of the participants at any time point. The investigators compared the women who

were easy to find with the women who were more difficult to track, and discovered that

the "easy to find" women were more likely to be white, were more highly educated, were

more likely to have access to cars, were less depressed, and had experienced less

psychological and physical abuse compared to the women who were more difficult to find

(Sullivan et al., 1996).

FVPSA Outcomes Evaluation: A Practical Guide page 22

The moral of the story is: If you do follow-up interviews with clients, be careful in

your interpretation of findings. The survivors you talk to are probably not representative of

all the people using your services. It is therefore our position that programs should not

waste the resources to gather information that is not likely to be accurate. Rather, they

should spend more time and attention engaging in outcome evaluation that is likely to give

them useful and trustworthy data.

Choosing Outcomes That Make Sense to Our Programs

One of the reasons that many domestic violence victim service program staff have

difficulty applying outcome evaluation to their work is that traditional outcome evaluation

trainings and manuals do not apply to our work. Instead they focus on programs that are

designed to change the behaviors of their clients: for instance, literacy programs are

designed to increase people’s reading and writing skills, AA programs are designed to help

people stay sober, and parenting programs are designed to improve the manner in which

people deal with their children. We, however, are working with victims of someone else’s

behavior. They did not do anything to cause the abuse against them, and we therefore are

not about changing their behaviors. For our work, then, we need to take a more expanded

view of what constitutes an outcome:

An OUTCOME

is a change in knowledge, attitude, skill, behavior,

expectation, emotional status, or life circumstance

due to the service being provided.

Some of our activities are designed to increase survivors’ knowledge (for example,

about the dynamics of abuse, typical behaviors of batterers, or how various systems in the

community work). We also often work to change survivors’ attitudes if they come to us

blaming themselves for the abuse, or believing the lies they have been told repeatedly by

the abuser (e.g., that they are crazy, unlovable, or bad mothers). We also teach many

FVPSA Outcomes Evaluation: A Practical Guide page 23

clients skills, such as budgeting and planning, how to behave during court proceedings or

how to complete a resume, and some clients do modify their behavior if they come to us

wanting to stop using drugs or alcohol, or wanting to improve their parenting.

Domestic violence victim service programs also change people’s expectations

about the kinds of help available in the community. For some clients we may lower their

expectations of the criminal legal system (for example if they think their abuser will be put

in prison for a long time for a misdemeanor) while for others we might raise their

expectations (for example if they are from another country and have been told by the

abuser that there are no laws prohibiting domestic violence).

Many of our services are designed to result in improved emotional status for

survivors, as they receive needed support, protection and information, and finally, we

change some clients’ life circumstances by assisting them in obtaining safe and affordable

housing, becoming employed, or going back to school.

REMEMBER: An OUTCOME

is a change in knowledge, attitude, skill, behavior, expectation,

emotional status, or life circumstance

due to the service being provided.

Because survivors come to us with different needs, from different life

circumstances, and with different degrees of knowledge and skills, it is important that our

outcomes first start with where each client is coming from. We do not, for example, want

to say that 90% of our clients will obtain protection orders, because we know that many

survivors do not want such orders or believe they would endanger them further. Instead,

then, we might say that: Of the women who want and are eligible for protection orders,

90% will accurately complete and file them.

"Problematic" Outcome Statements to Avoid

A common mistake made by many people designing project outcomes is

developing statements that are either (1) not linked to the overall program's objectives, or

(2) unrealistic given what the program can reasonably accomplish. Five common

FVPSA Outcomes Evaluation: A Practical Guide page 24

problematic outcome statements are listed on the following pages, with explanations for

why they should be avoided:

Problematic Outcome Statement #1

"50% of the women who use this service will leave their abusive partners."

The expectation that all battered women should leave their abusive partners is

problematic for a number of reasons, including: it wrongly assumes that leaving the

relationship always ends the violence, and it ignores and disrespects the woman's

agency in making her own decision. This type of "outcome" should either be

avoided altogether or modified to read, 'xx% of the women using this service who

want to leave their abusive partners will be effective in doing so.'

Problematic Outcome Statement #2

"The women who use this program will remain free of abuse."

Victim-based direct service programs can provide support, information,

assistance, and/or immediate safety for women, but they are generally not

designed to decrease the perpetrator's abuse. Suggesting that victim

focused programs can decrease abuse implies the survivor is at least

somewhat responsible for the violence perpetrated against her.

Problematic Outcome Statement #3

"The women who work with legal advocates will be more likely to press charges."

Survivors do not press charges; prosecutors press charges. It should also not be

assumed that participating in pressing charges is always in the woman's best

interest. Legal advocates should provide women with comprehensive information

to help women make the best-informed decisions for themselves.

Problematic Outcome Statement #4

"The women who work with legal advocates will be more likely to cooperate with

the criminal justice system."

Again, women should be viewed as competent adults making the best decision(s)

they can for themselves. Women who choose not to participate in pressing

charges should not be viewed as "noncompliant" or "uncooperative." Until the

criminal justice system provides women with more protection, and eliminates

gender and racial bias and other barriers to justice, it should not be surprising when

women choose not to participate in the criminal justice process.

FVPSA Outcomes Evaluation: A Practical Guide page 25

Problematic Outcome Statement #5

"An outcome of this program will be that the number of calls to the police will

decrease."

First, if this is not a well-funded research study you probably will not have the

resources to find out if calls to the police decrease. But more importantly, a

decrease in the number of calls to the police does not necessarily mean violence

has decreased. It could mean women are more hesitant to contact the police or

that perpetrators are more effective in preventing women from calling the police.

That some programs feel compelled by funders to create outcome statements such

as these is understandable. However, the cost is too high to succumb to this urge. It is one

of our goals to educate the public about domestic violence, and that includes our funders.

If funders have money to spend to eradicate domestic violence, we must educate them

about the appropriate ways to spend that money. We can not do that effectively unless

they understand why abuse occurs in relationships, and that survivors are not responsible

for ending the abuse.

The Hard-to-Measure Outcomes of Domestic Violence

Programs

Why is it so difficult to evaluate domestic violence programs? In addition to the

obvious answer of "too little time and money," many domestic violence programs' goals

involve outcomes that are difficult to measure. An excellent resource for designing

outcomes within non-profit agencies is "Measuring program outcomes: A practical

approach," distributed by the United Way of America (see List of Additional Readings in

the back of this manual for more information). In an especially applicable section entitled

"Special problems with hard-to-measure outcomes" (p. 74), the United Way manual lists

nine situations that present special challenges to outcome measurement. They are

included here, since one or more are evident in most domestic violence programs. Where

applicable, the statement is followed by the type of domestic violence service that is

especially susceptible to this problem:

FVPSA Outcomes Evaluation: A Practical Guide page 26

1. Participants are anonymous, so the program cannot later follow up on the

outcomes for those participants. 24-hour crisis line

2. The assistance is very short-term. 24-hour crisis line; sometimes support groups,

counseling, shelter services, some legal advocacy

3. The outcomes sought may appear to be too intangible to measure in any systematic

way. 24-hour crisis line, counseling, support groups, some shelter services

4. Activities are aimed at influencing community leaders to take action on the part of

a particular issue or group, such as advocacy or community action programs.

systems advocacy programs

5. Activities are aimed at the whole community, rather than at a particular, limited set

of participants. public education campaigns

6. Programs are trying to prevent a negative event from ever occurring.

7. One or more major outcomes of the program cannot be expected for many years,

so that tracking and follow-up of those participants is not feasible.

8. Participants may not give reliable responses because they are involved in substance

abuse or are physically unable to answer for themselves.

9. Activities provide support to other agencies rather than direct assistance to

individuals.

On the one hand, it is heartening to know that (1) the United Way of America

recognizes the challenges inherent to some organizations' efforts, and (2) it is not [simply]

our lack of understanding contributing to our difficulty in creating logic models for some of

our programs. On the other hand, just because some of our efforts are difficult to measure

does not preclude us from the task of evaluating them. It just means we have to try harder!

We have included logic models for some of the common domestic violence services being

offered, in case those would be helpful to you with other funders. They can be found in

Appendix A.

FVPSA Outcomes Evaluation: A Practical Guide page 27

So, What is an Outcome Measure?

Outcome measures are sources of information that tell us whether or to what extent

an outcome has been achieved. So, for example, if the desired outcome is that women

who use our services will know more about community resources, how would we know

whether that had occurred? We might develop a brief survey for them to complete, or we

might interview them face-to-face with a questionnaire....these different ways to determine

whether the outcome has been achieved are called outcome measures because they

measure, or document, whether the change has occurred.

Common types of outcomes measures are:

Paper and pencil surveys

Questionnaires completed in interview format

Mail surveys

Telephone surveys

Staff documentation (for example, documentation regarding how many

protection orders were filed)

In the late 1990s the Documenting Our Work (DOW) project was initiated

nationally to examine the efforts, successes and challenges of the Battered Women’s

Movement. One component of that project was to design outcome evaluation strategies

that local programs could use to evaluate their work. Because the DOW project is directly

relevant to the FVPSA outcomes project, the next chapter describes DOW and its findings

in more detail.

FVPSA Outcomes Evaluation: A Practical Guide page 28

Chapter Six

The Documenting Our Work Project

We describe the Documenting Our Work project here in some detail for several reasons:

It provides useful examples of short-term outcomes measures.

It includes the two outcomes that will be required by FVPSA.

It involves collecting information from survivors, which includes

documentation of the services they wanted.

It was created by people who work in the domestic violence movement.

It involved testing the forms and making changes based on the results.

A Brief History of Documenting Our Work

The National Resource Center on Domestic Violence (NRC) initiated the

Documenting Our Work (DOW) Project in 1998 following discussions among state

coalition directors, women of color activists, and FVPSA state administrators. They agreed

on the need to carefully develop tools for the domestic violence field that would document

its work with and on behalf of battered women at both the state and local levels. There

was a commitment to use this documentation to strengthen and inform program, policy

and research, to increase our understanding of its impact on individuals and communities,

and to help guide future directions. The NRC formed a multi-disciplinary advisory group of

evaluators, coalition directions, local program directors, and state administrators to begin

exploring definitions, goals and objectives, and measures.

During the initial stages of the project, a tremendous amount of information was

collected from the field through targeted focus groups with representative from

underserved communities, from advisory group meetings and conference calls, and

through discussions with others engaged in documentation and outcome measurement.

One result of the Documenting Our Work Project was the development of a

number of tools that programs and coalitions can use to evaluate themselves. They are:

FVPSA Outcomes Evaluation: A Practical Guide page 29

State Coalitions Tools

1. A tool for community partners to complete that documents the coalition’s

community collaboration efforts;

2. A tool for staff to complete that documents the coalition’s community

change efforts; and

3. A tool for staff to complete that is an internal assessment of the coalition’s

goals and activities.

Local Program Tools

1. A tool for community partners to complete that documents the program’s

community collaboration efforts;

2. A tool for community members to complete that documents how the

program is perceived and supported in the community;

3. A tool for staff to complete that documents the program’s systems change

efforts; and

4. A tool for staff and volunteers to complete about their experience working

in the program: their activities, training, support, involvement in decisions,

and other issues.

Local program assessment tools that have been designed for survivors to

complete include surveys evaluating the following services: Shelter, Support Services

and Advocacy, Support groups, and Counseling. A 24-hour hotline form was also

developed that staff members complete at the end of crisis calls.

In examining the DOW client-centered surveys it became clear that questions were

already embedded in them that could be modified slightly to measure the two FVPSA

outcomes. Specifically, wording could be in the form of statements that clients can

either agree or disagree with:

Because of the services I have received from this program so far, I feel I

know more about community resources.

Because of the services I have received from this program so far, I feel I

know more ways to plan for my safety.

FVPSA Outcomes Evaluation: A Practical Guide page 30

The DOW tools had also been pilot-tested across programs from four different

states in order to determine if they were brief, clear, easy to use, and viewed favorably

by both survivors and program staff members. Some of the findings from that pilot are

presented below.

Results of the DOW Pilot of Shelter Forms

Two forms were created for shelter residents. The first survey, designed to be

completed by residents shortly after arriving at the shelter, included questions about

how women heard about the shelter, what their preconceived ideas about it were, and

the kinds of help they were looking for. The second survey, which is completed shortly

before women leave shelter, asks about the extent to which women’s needs were met

by the program. Questions also pertain to how long the woman was at shelter, her

experience with rules and other residents, and whether she would recommend the

program to a friend in similar need. The forms were completed by 75 women across

programs in four states.

• 44% completed form 1 only

• 19% completed form 2 only

• 37% completed both forms

A few brief findings from the pilot are presented here, to give you a flavor of the types of

helpful information programs can get from their clients.

Residents were asked what the experience was like for them upon entering shelter.

Women responded:

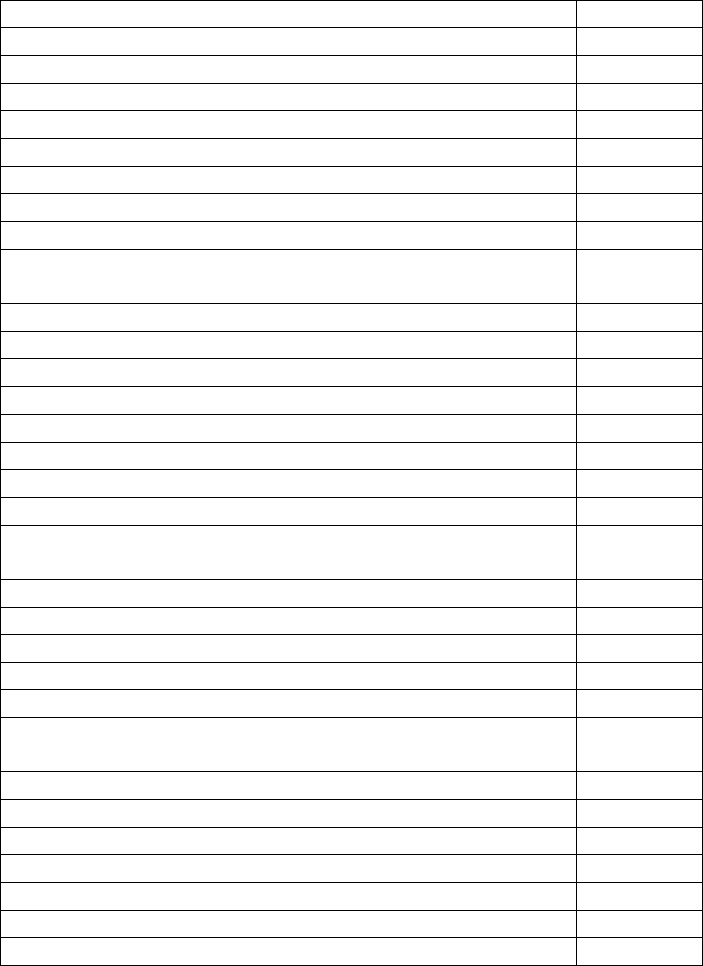

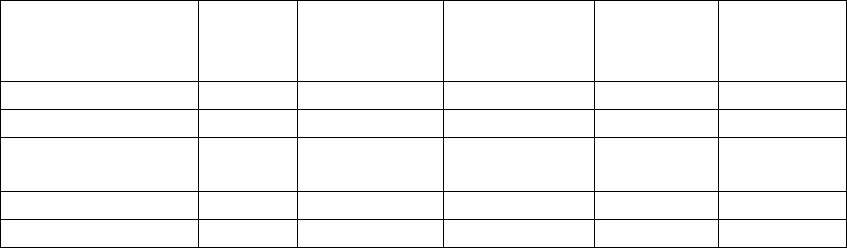

Table 1. When I First Arrived…

Staff made me feel welcome

95%

Staff treated me with respect

93%

The space felt comfortable

85%

Other women made me feel welcome

78%

It seemed like a place for women like me

73%

FVPSA Outcomes Evaluation: A Practical Guide page 31

Shelter staff seeing these results would feel pleased that survivors felt welcomed

and treated with respect when they first entered the program.

Another interesting finding was that 23% of the women had “concerns” about

contacting shelter. The most common concerns were:

• Shame or embarrassment about abuse

• Safety at the shelter

• Fear of the unknown—didn’t know what to expect

Women were also asked to check off all of the kinds of help they were looking

for while in shelter. Their responses are in the next table.

Table 2. Kinds of Help Women Wanted at Shelter Entry

• Safety for myself

88%

• Paying attention to my children’s wants and needs*

88%

• Learning about my options and choices

85%

• Paying attention to my own wants and needs

85%

• Understanding about domestic violence

83%

• Counseling for myself

83%

• Learning how to handle the stress in my life

81%

• Finding housing I can afford

81%

• Emotional support

80%

• Connections to other people who can help me

78%

• Safety for my children*

73%

• Support from other women

70%

• Dealing with my children when they are upset

• or causing trouble*

65%

• A job or job training

59%

• Health issues for myself

58%

• Strategies for enhancing my own and my children’s safety

56%

• Counseling for my children*

56%

• Planning ways to make my relationship safer

51%

• Custody or visitation questions*

50%

• Budgeting and handling my money

49%

• Education/school for myself

48%

• Education for my children*

46%

• Health issues for my children*

46%

• Transportation

46%

• Other government benefits

44%

• Legal system/legal issues

44%

• Reconnecting with my community

42%

• Leaving my relationship

42%

FVPSA Outcomes Evaluation: A Practical Guide page 32

Table 2. Kinds of Help Women Wanted at Shelter Entry (continued)

• TANF (welfare) benefits

34%

• Child protection system issues*

29%

• Protective/restraining order

27%

• My abuse-related injuries

20%

• My abuser’s arrest

17%

• My own arrest

9%

• My children’s abuse-related injuries*

8%

• Immigration issues

7%

*Items were responded to by mothers only

This simple listing can be enormously helpful for program planning—to make sure

that the program emphasizes the services most needed by women, to the extent it can—

and for fund-raising. Most program staff would expect that women’s safety would be at the

top of the list. Some might be surprised, however, that help with “paying attention to my

own wants and needs” was ranked so high among all of the choices available. Others

might find it worth noting that help with “leaving my relationship” was checked by less

than half of the women in this test. Although help with “immigration issues” was checked

by a small percentage, this result is likely to vary by location. This type of response could

alert a program to unknown gaps in service, and lead to increased resources.

Useful information was obtained from the survey completed by women upon

shelter exit as well. For example, women were asked to indicate, for every need they had

while in shelter, whether they received all the help they needed, some of the help they

needed, or none of the help they needed with that issue. Some of the findings are in the

following table.

Table 3. Extent of Help Women Received While in Shelter *

Type of help needed:

All

Some

Safety for myself

98%

2%

Learning about my choices and options

67%

30%

Learning to handle stress in my life

65%

27%

Finding affordable housing

51%

34%

Budgeting and handling my money

38%

26%

Job or job training

36%

24%

* Results are only for women who indicated they wanted this type of help

FVPSA Outcomes Evaluation: A Practical Guide page 33

It is important that these results distinguish those who wanted the service from

those who did not. It shows that 98% of the women who wanted safety for themselves got

all of that kind of help that they wanted. This was also true for 71% of the women who

wanted help with “understanding about domestic violence” (not shown in the table); the

remainder reported that they got “some of” that kind of help. Interestingly, all of the

women who stayed in shelter for two months or more got all the help they wanted with

understanding domestic violence.

The survey women complete upon shelter exit is also extremely useful for

outcome evaluation. A number of the items on the survey ask specifically about how

the shelter experienced affected women’s lives. Some of these outcome findings are in

the next table.

Table 4. Because of My Experience in the Shelter, I Feel:

(%s do not total 100 because women could check more than one)

Better prepared to keep myself and my children safe

1

92%

More comfortable asking for help

90%

I have more resources to call upon when I need them

87%

More hopeful about the future

87%

I know more about my options

87%

More comfortable talking about things that bother me

82%

That I will achieve the goals I set for myself

79%

I can do more things on my own

79%

More confident in my decision-making

76%

These are certainly positive results—especially when a quarter of the women had

been in shelter a week or less. Over three-quarters of the women who stayed in the shelter

felt more confident of their decisions and abilities, and nearly nine out of ten felt better

informed and more comfortable asking for help. These are among the outcomes most

shelter staff would hope that residents would attain. In addition, the overwhelming

majority of women who participated in the pilot indicated that they had obtained safety

and emotional support during their time in the shelter.

1

This option was on the original shelter #2 form, and clearly was the one most frequently selected by women in the

pilot test. However, discussion with advisors concluded that it sounded too much like the women had control over their

safety (and their abusive partners’ use of violence against them, in particular), so it has been changed to “I know more

ways to plan for my safety” on the latest version of the form.

FVPSA Outcomes Evaluation: A Practical Guide page 34

These findings can be used to identify training needs, or to provide examples to

illustrate training issues programs already cover. For example, at shelter entry 73% of the

respondents checked “[the shelter] seemed like a place for women like me.” However,

when this item was examined across different racial and ethnic groups it was found that

Latinas were less likely than other women to check this response –just 57% did. This

finding might be shared with staff, so that culturally appropriate welcoming strategies

could be emphasized. Alternatively, this finding might highlight a resource issue – a need

for more bicultural staff, or modifications in shelter décor.

The questions on Shelter form #2 that asked about the help women and children

received can also identify training-related needs. For example, about 4 out of 5 women

indicated they wanted help “learning how to handle the stress in my life.” Of those,

however, 8% indicated they did not get help with this issue, and another 27% did not get

as much help as they wanted. This might be a useful topic to elaborate on in training with

staff and volunteers. Similarly, half of the women wanted help with “budgeting and

handling my money,” but over a quarter of this group did not get any help with this issue.

Information about budgeting can be invaluable for women trying to move toward

independence and self-sufficiency for the first time; making sure that staff and volunteers

are prepared to assist effectively may be a very useful part of comprehensive services.

These are just a few examples out of many ways that collecting this information

from survivors in shelter can help programs become more responsive to women’s needs.

Results of the DOW Pilot of Support Services & Advocacy Forms

This survey was created to obtain brief, specific feedback from women receiving

support services. The forms capture the types of help clients wanted, as well as what they

received. Survivors also indicate how many times they met with an advocate, their feelings

about how respected and supported they felt, and overall how satisfied they were with the

services.

Three states participated in piloting these forms, and 42 women responded. Most

(77%) were under the age of 35, and 40% were women of color.

The following table presents the types of assistance women reported wanting from

the domestic violence program’s support services:

FVPSA Outcomes Evaluation: A Practical Guide page 35

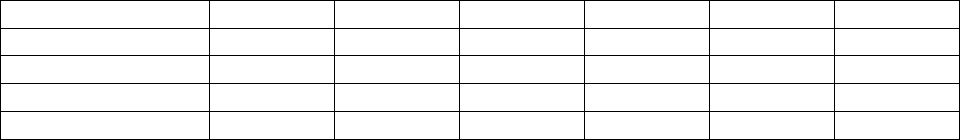

Table 5. Types of Advocacy Women Mentioned Wanting

(Percents do not total 100 because women could check more than one)

Help getting safe and adequate housing

52%

Information about the legal system process

38%

Information about my legal rights and options

29%

Help with a protective order

26%

Help with police issues

21%

Help arranging transportation to meet my needs

21%

Someone to go with me to court

19%

Help with government benefits (e.g. welfare/TANF)

19%

Help getting access to mental health services

19%

Help supporting the court case against the person who

abused me

17%

Access to an attorney

17%

Help with budgeting

14%

Help keeping custody of my children

14%

Help getting child support

14%

Help getting access to child care

14%

Help getting a job

12%

Help getting access to health care

12%

Help with health insurance for my children

10%

Help understanding my rights and options related to

residency

10%

Help with probation issues

7%

Help preparing to testify in court

7%

Help meeting my needs related to my disability

7%

Help with safe visitation for my children

7%

Help with child protection hearings or requirements

7%

Help with my children’s school (e.g. records, changing

schools)

7%

Help getting medical benefits (e.g. Medicaid)

7%

Help dealing with my arrest

5%

Help getting job-related training

5%

Help meeting my child’s disability-related needs

5%

Help getting residency status

5%

Help getting benefits as an immigrant

2%

Help getting access to substance abuse services

2%

This information can be quite helpful for program planning and for fund-raising.

The fact that the most common help women reported needing was affordable housing

might surprise some community members and funders, and could positively influence a

program’s application for more money to devote to this. Also, 7% of the women wanted

help with their own disability and 5% needed help for their child’s disability. While not

FVPSA Outcomes Evaluation: A Practical Guide page 36

large percentages, this could still represent a significant number of families in need of these

specialized services.

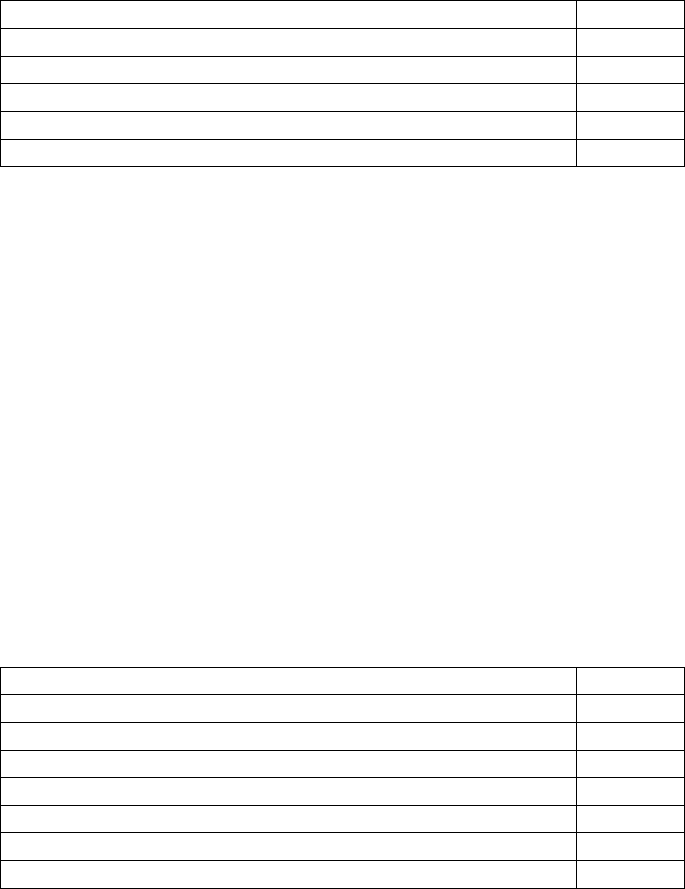

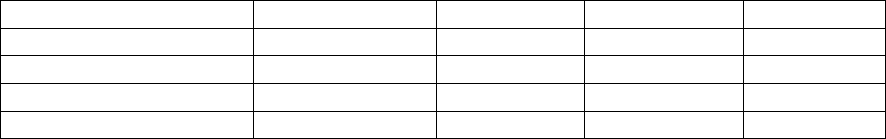

Outcome information for support services was quite interesting as well, as shown

in the following table. Notice that the numbers are generally lower than what was

reported by shelter residents. This could be a function of fewer contacts with advocates,

but deserves additional attention.