The Economic and Social Benefits of the TAFE System 1

+

An Investment in

Productivity and

Inclusion:

The Economic and Social

Benefits of the TAFE System

By Alison Pennington

Centre for Future Work at the Australia Institute

August 2020

The Economic and Social Benefits of the TAFE System 2

About The Australia Institute

The Australia Institute is an independent public policy think

tank based in Canberra. It is funded by donations from

philanthropic trusts and individuals and commissioned

research. We barrack for ideas, not political parties or

candidates. Since its launch in 1994, the Institute has carried

out highly influential research on a broad range of economic,

social and environmental issues.

Our Philosophy

As we begin the 21st century, new dilemmas confront our

society and our planet. Unprecedented levels of consumption

coexist with extreme poverty. Through new technology we are

more connected than we have ever been, yet civic engagement

is declining. Environmental neglect continues despite

heightened ecological awareness. A better balance is urgently

needed.

The Australia Institute’s directors, staff and supporters

represent a broad range of views and priorities. What unites us

is a belief that through a combination of research and creativity

we can promote new solutions and ways of thinking.

Our Purpose—‘Research That Matters’

The Institute publishes research that contributes to a more

just, sustainable and peaceful society. Our goal is to gather,

interpret and communicate evidence in order to both diagnose

the problems we face and propose new solutions to tackle

them.

The Institute is wholly independent and not affiliated with any

other organisation. Donations to its Research Fund are tax

deductible for the donor. Anyone wishing to donate can do so

via the website at https://www.tai.org.au or by calling the

Institute on 02 6130 0530. Our secure and user-friendly

website allows donors to make either one-off or regular

monthly donations and we encourage everyone who can to

donate in this way as it assists our research in the most

significant manner.

Level 1, Endeavour House, 1 Franklin St

Canberra ACT 2601

Tel: (02) 6130 0530

Email: [email protected]

Website: www.tai.org.au

About the Centre for Future Work

The Centre for Future Work is a research centre, housed within

The Australia Institute, to conduct and publish progressive

economic research on work, employment and labour markets.

It serves as a unique centre of excellence on the economic

issues facing working people: including the future of jobs,

wages and income distribution, skills and training, sector and

industry policies, globalisation, the role of government, public

services and more. The Centre also develops timely and

practical policy proposals to help make the world of work

better for working people and their families.

www.futurework.org.au

About the Author

Alison Pennington is Senior Economist with the Centre for

Future Work. Her research focus is on work in Australia today,

and in the future. She received a Master of Political Economy

from the University of Sydney.

The author thanks without implication Jonathan Guy and Jim

Stanford for helpful comments.

The Economic and Social Benefits of the TAFE System 3

Table of Contents

Introduction and Summary ........................................................................................................ 4

Benefits .................................................................................................................................. 5

Costs ....................................................................................................................................... 7

Cost-Benefit Comparisons ..................................................................................................... 8

Policy Implications ................................................................................................................. 9

Overview of this Paper ........................................................................................................... 9

The Crisis of Australian VET Policy ........................................................................................... 11

Reduced Enrolments ............................................................................................................ 12

Reduced Funding ................................................................................................................. 15

TAFE System Eroded ............................................................................................................ 17

The COVID Recession, Jobs and Skills ...................................................................................... 20

Review of Published Research ................................................................................................. 22

Costs of the TAFE System ......................................................................................................... 27

Benefits of the TAFE System .................................................................................................... 34

Economic Benefits of TAFE Production ............................................................................... 34

Labour Market Benefits ....................................................................................................... 39

Fiscal Savings and Social Benefits ........................................................................................ 46

Wider Social Benefits ........................................................................................................... 49

Comparing the Costs and Benefits ........................................................................................... 52

Conclusion and Recommendations ......................................................................................... 55

Appendix .................................................................................................................................. 58

Deriving TAFE’s Share of VET-Qualified workers ................................................................. 58

Calculating Unemployment & Benefit Payments ................................................................ 59

Calculating Healthcare Savings Benefits .............................................................................. 61

References ............................................................................................................................... 64

The Economic and Social Benefits of the TAFE System 4

Introduction and Summary

Australia currently faces its most significant economic challenge in many decades. COVID-19

has resulted in the shutdown of large segments of the economy and the destruction of

hundreds of thousands of jobs. With private incomes collapsing, business confidence

shattered and global supply chains disrupted, it will take many years to rebuild the economy

and enable Australians to start working again to their full potential. There is no doubt that

young workers will be hardest hit by high unemployment and underemployment in coming

years.

Training will play a vital role in reorienting the economy after the pandemic, facilitating

crisis-accelerated transitions across industries and supporting millions of workers (both new

entrants to the labour force, and existing workers displaced by the pandemic and its after-

effects) to prepare for future jobs. But Australia’s vocational education and training (VET)

system requires urgent rebuilding to ensure it can support new skills acquisition, job-

creation, and opportunity – including for those segments of Australia’s population hardest-

hit by the crisis (such as young people, women, and workers in regional communities).

Unfortunately, the VET sector enters this tumultuous period having already experienced a

profound and multidimensional crisis from policy failures and fiscal mismanagement during

previous years. These problems remain entrenched. Understanding where policy went

wrong will be critical to ensuring that VET plays its proper role in a comprehensive public

policy-led national reconstruction effort.

Enrolments in apprenticeships and traineeships had already collapsed after 2012. Current

projections now predict a further 30% drop in new apprenticeships (with 130,000 fewer

positions) resulting from the pandemic to 2023 (Mitchell Institute, 2020). Yet even as the

number of apprentices contracts, employers report prolonged skills shortages in technical

and trades occupations; meanwhile, the number of young people neither in education nor

in work is exploding. Dramatic restructuring of the VET system from the 2000s, based on

market-based delivery of programs underpinned by massive public subsidies paid to private

providers, failed to create the stable, high-quality vocational education system that the

economy needs so badly now. Private providers received enormous public subsidies, only to

come and go—sometimes even collapsing mid-program, or leaving students with poor-

quality credentials. At the same time, governments have dramatically cut funding to the

longest-standing and most reliable national provider of VET education: Australia’s once

world-renowned Technical and Further Education (TAFE) institutes. Coordinated and

effective ties between students, TAFE institutes, industry and employers have been

undermined. Once-reliable vocational pathways have been deeply damaged.

The Economic and Social Benefits of the TAFE System 5

In this report we present robust and up-to-date evidence on the broad economic benefits of

the TAFE system to Australia’s future economy. This report makes a new contribution to the

study of the economic impacts of both VET broadly, and the TAFE system specifically, in

Australia. We adopt a multidimensional approach to measuring the economic and wider

social benefits of vocational education. Our cost-benefit methodology is guided both by a

review of the extant literature, and by original research to identify and quantify the broad

economic and social benefits of vocational education. To calculate the wide-ranging

economic impacts and social benefits of the TAFE system, we use a range of quantitative

data from multiple official sources—including the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS); the

National Centre for Vocational Education Research (NCVER); the Commonwealth

Department of Education and Training; the Commonwealth Department of Employment,

Skills, Small and Family Business; and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and

Development (OECD).

Here are our key findings:

BENEFITS

Despite years of significant funding pressure and policy confusion, the TAFE system

continues to make a strong and disproportionate economic and social contribution to the

Australian economy. The economic and social benefits arising from the direct activity of

TAFE institutes, and the highly-skilled higher-earning workforce that the system has helped

develop, are substantial. As outlined below, our quantitative benefits assessment has been

organised into four benefits ‘streams’: each capturing different ways in which the TAFE

system interacts with, and impacts the economy. In addition, we consider wider social

benefits that the TAFE system generates, but which are harder to quantify.

The Economic Footprint of the TAFE System

The direct operation of TAFE institutes produces about $3 billion per year in additional

value-added in Australia, including around $2.3 billion in wages, salaries and other

employment benefits paid annually. Purchases and supply chain inputs associated with

TAFEs extend and multiply this impact on the broader national and regional economies,

generating another $1.6 billion per year in ‘upstream’ economic benefits. Counting the

indirect jobs supported in the TAFE supply chain, a total of $3 billion in employment

incomes is generated by TAFE institutes each year. In turn, that income translates into an

additional $1.5 billion in incremental consumer spending on Australian-made goods and

services. Including the direct activity of the TAFEs, its supply chain, and ‘downstream’

consumer spending impacts, we estimate that a total of over $6 billion in economic activity,

supporting 48,000 positions (directly and indirectly), is generated by the presence and

activity of Australia’s TAFE institutes.

The Economic and Social Benefits of the TAFE System 6

Increased Earnings and Productivity

Students who complete VET qualifications with TAFE institutes move into the labour force

with skills that generate higher earnings compared to the earnings of workers without post-

school qualifications. Employees and owner-managers with VET qualifications (including

Certificate I/II/III/IV, Diploma and Advanced Diploma) receive a wage premium of 39%

compared with those whose highest educational attainment is Year 12 or below.

In addition, a more skilled workforce yields significant productivity benefits to employers, as

well as higher tax revenues for government. The total annual benefit that the TAFE system

generates thanks to its accumulated contribution to the skills of Australians is estimated at

$84.9 billion. Some of this is paid in higher incomes to workers; some of it is captured in

higher profits by employers. And some of it is paid in incremental taxation revenues to

government, which we estimate are worth $25 billion per year—several times more than

governments currently allocate to the cost of running the entire TAFE system.

Stronger Employment Outcomes

After training, TAFE graduates are more likely to be employed, and less likely to be

unemployed, than workers with less training. Moreover, with increased access to skilled

workers, industry can expand production and employ more people, increasing total output

across the economy. We estimate the TAFE system has increased the employability of the

VET-educated population, relative to those without post-school education, resulting in an

increase in employment of around 486,000 positions.

Reduced Fiscal Outlays

The TAFE system increases employability, thereby lowering unemployment and supporting a

healthier workforce and society. An important consequence of this is reduced social

assistance and public healthcare expenditures. We estimate the annual value of reduced

social expenses at some $1.5 billion per year.

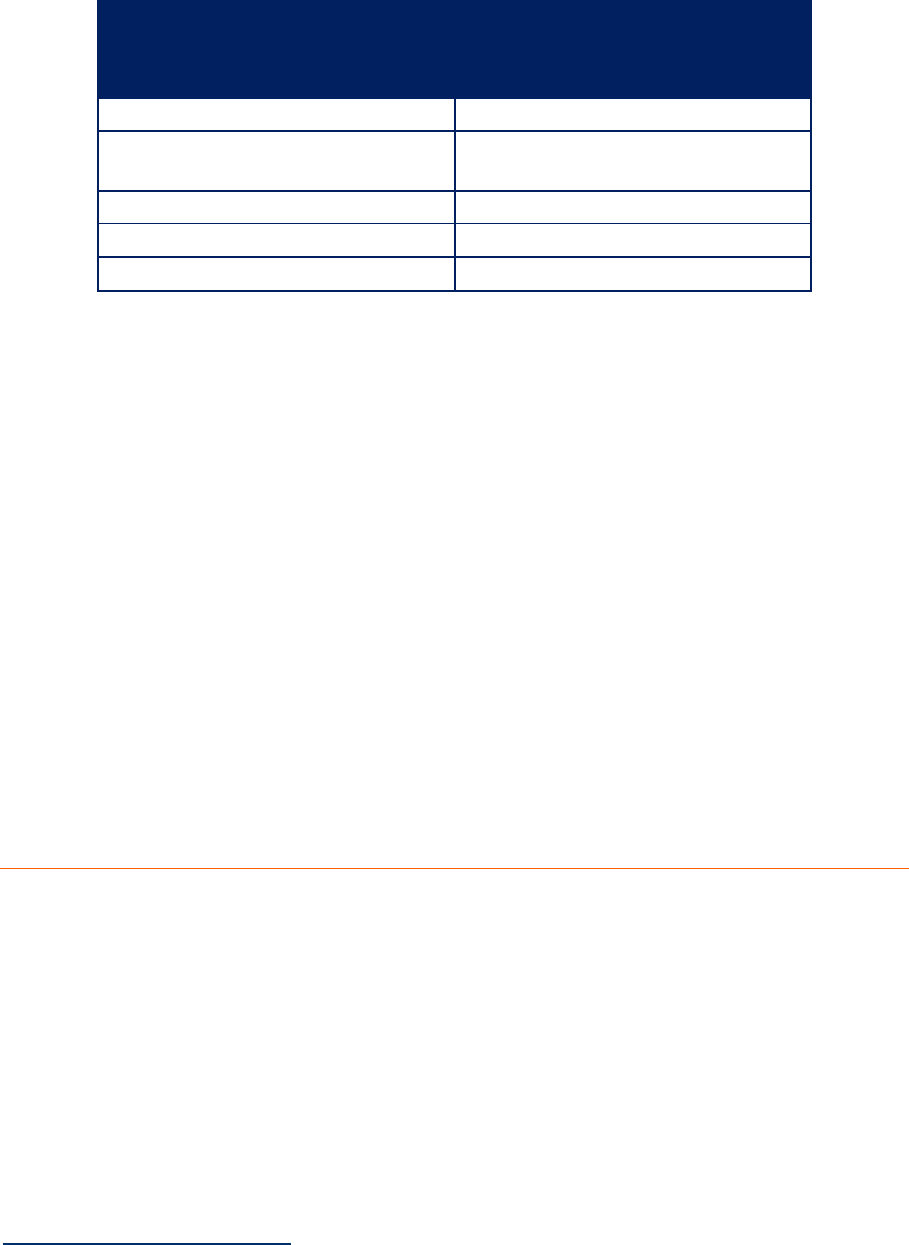

Combined Benefits

Table 1 provides a summary of the annual impacts of TAFE across these key economic

indicators. The total annual benefit (driven by the accumulated historic investment in the

TAFE-trained workforce) is estimated at $92.5 billion. That represents around 4.5% of

Australian GDP. Those benefits can be traced back to the extra employability, productivity

and incomes (and associated savings on social benefit costs) demonstrated by the TAFE-

educated workforce.

The Economic and Social Benefits of the TAFE System 7

Table 1

TAFE Annual Economic Impact Results

TAFE Economic Footprint

$6.1 billion

Higher Earnings and Productivity

(Includes Higher Tax Revenues)

$84.9 billion

($25 billion)

Fiscal Savings (Social Benefits)

$1.5 billion

Total Benefit

$92.5 billion

Total Annual Costs

$5.7 billion

Wider Social Benefits

The substantial economic benefits supported by the TAFE system, quantified in Table 1, do

not tell the whole story about the importance of TAFEs to our all-round economic and social

well-being. The TAFE system also underpins a wide range of broader social benefits that are

harder to quantify. For example, TAFEs promote stronger economic and labour market

outcomes in regional areas. They help ‘bridge’ access to further education and jobs

pathways for special and at-risk groups of young Australians. They ensure greater social

cohesion, and help to reduce crime. TAFE students are more likely to come from the lowest

quintile of society according to socio-economic disadvantage,

1

more likely to be Aboriginal

or Torres Strait Islander, and more likely to identify as having a disability compared with

students of private VET providers or universities. All these features confirm that TAFEs are

critically important in addressing systemic inequality in Australia’s economy and society.

COSTS

The costs of operating the TAFE system accrue to governments, students and employers in

the delivery of vocational education through TAFE institutes. Compared to the preceding

inventory of direct and indirect economic and social benefits, the costs of operating the

TAFE system are modest by any measure. We estimate the combined costs of the TAFE

system—including government funding for training and administration, employer and

student assistance, loans and income support payments, student fees, and employer

apprenticeship and traineeship training costs—at $5.7 billion per year. That represents only

about 0.3% of Australia’s GDP.

1

NCVER statistics measure disadvantage among VET and university students according to the ABS Index of

Relative Socio-economic Disadvantage (IRSD). IRSD is a socio-economic index that summarises a range of

indicators about the economic and social conditions of individuals and households within an area, including

income and educational attainment. Low quintile scores indicate greater disadvantage relative to higher

quintiles (NCVER, 2020).

The Economic and Social Benefits of the TAFE System 8

COST-BENEFIT COMPARISONS

The TAFE system has made a leading, decades-long contribution to training and skills in the

Australian economy. On the basis of historical enrolment data, we estimate that 72.5% of

Australian workers currently holding VET qualifications received their training through the

TAFE system. Hence, Australia’s historic investment in quality public vocational education

generates an enormous and ongoing dividend, in the form of the enhanced productivity,

higher earnings, increased tax payments, and reduced social benefit costs associated with

those workers. This is a valuable and continuing payoff to the funds that were invested in

TAFEs: both now and in the past.

There is no doubt that the benefits of TAFE education to individuals, employers, the

government and wider society far outweigh the costs. As noted, the combined annual costs

for operating the TAFE system’s 35 institutes were modest—$5.7 billion. In contrast, the

annual economic benefits generated thanks to investments in TAFE-provided training were

estimated at $92.5 billion. In other words, the flow of annual benefits resulting from the

present and past operation of the TAFE system exceed the current annual costs of operating

that system by a factor of 16 times.

Keep in mind that the flow of these economic benefits resulting from a better-skilled

workforce is the legacy of Australia’s historic commitment to high-quality public vocational

education. But that commitment has been undermined in recent years by reductions in

fiscal support for public VET, and failed policy experiments with privatised, market-

delivered, but publicly-subsidised VET programs. As a result, the flow of economic benefits

generated by well-trained, better-paid VET graduates is in jeopardy today. Australia is not

replacing its stock of high-quality TAFE graduates – which means that over time, that flow of

economic benefits will inevitably decline. Reported problems encountered by many

industries and employers in recruiting and retaining adequately-skilled workers in numerous

occupations attests to the growing costs of Australia’s underinvestment in reliable, publicly-

delivered VET.

A fitting analogy can be drawn to other long-term investments that deliver an ongoing flow

of benefits – but which must be adequately maintained if that flow of benefits is to

continue. Imagine a well-built house: it generates value each year that someone lives in it.

But if the house is not maintained, and its structural integrity assured, then that flow of

benefits will quickly erode. Australia’s economy today is reaping an enormous flow of

economic benefits from a ‘house’ that was built by our TAFE system: $92.5 billion in annual

productivity, income, tax, and social benefits. But the TAFEs today have been structurally

damaged by neglect and outright policy vandalism. If we want to continue reaping those

benefits of a superior productive TAFE-trained workforce, we must repair that damage –

and quickly. With the COVID-19 pandemic ushering in an era of unprecedented disruption

and transition, this is the moment to strengthen Australia’s investments in the TAFE system.

The Economic and Social Benefits of the TAFE System 9

We can make our vocational training system once again the envy of the world, and ensure

that our economy, our communities, and our governments continue to reap the benefits of

a productive, well-trained workforce.

POLICY IMPLICATIONS

Australia desperately needs a thorough overhaul of VET sector policy, and a lasting

commitment to repairing a badly-damaged VET system. As the economy staggers in the face

of the COVID-19 pandemic and resulting global recession, we need expanded access to VET

education, stronger pathways from training to work, and a more cohesive and coordinated

post-school education system. Revitalised TAFE institutes, as the most reliable ‘anchors’ of

vocational training, must be at the centre of that reconstruction process.

There is a fitting historical analogy for the present imperative to repair our VET system,

starting with the TAFEs. After the Second World War, Australia launched a coordinated

national training strategy, as a key part of a National Reconstruction Plan aimed at ensuring

returning soldiers would have productive employment opportunities – and making sure the

economy did not slip back into a stubborn depression.

2

We need a similarly comprehensive

national strategy for skills and training today, starting with the urgent restoration of public

funds to the most experienced, reliable and high-quality, national-level, vocational training

provider in Australia: the TAFE system.

Our findings suggest there is strong economic rationale for strengthening and expanding

VET access for young, at-risk groups, and for all workers who lack post-school qualifications.

Australia will squander the demonstrated and ongoing economic benefits generated by our

investments in TAFE institutes, and unduly limit our post-COVID reconstruction

opportunities, if we do not act quickly to reinstate the funding and critical role that TAFE

plays in the VET system.

OVERVIEW OF THIS PAPER

The remainder of this paper is organised as follows. First, we review the history of

underfunding and failed market-based policies that have left Australia’s VET system in such

poor shape to respond to the crisis of the pandemic and resulting recession. The next

section then discusses how this legacy of policy failure has left the VET system poorly

prepared to confront the unprecedented labour market challenges arising from the COVID-

2

The National Reconstruction Plan was launched by the Commonwealth Government in 1942, years before the

eventual cessation of hostilities, and featured several complementary elements: including building national

manufacturing and infrastructure, extending public education and vocational training, expansionary macro-

economic policies, and a commitment to full employment. For more on Australia’s experience with 1940s

reconstruction, see MacIntyre (2015).

The Economic and Social Benefits of the TAFE System 10

19 pandemic and associated recession. The following section reviews the methodology and

findings of other published research, which has also attempted to analyse the costs and

benefits of public and social programs. The next sections of the report review and quantify

the benefits and costs associated with the TAFE system in detail, broken into various

categories and components. The benefits include the direct economic injections resulting

from the operation of TAFE institutes, the superior productivity and income flows resulting

from the TAFE-trained workforce, and the broader (often non-quantifiable) social benefits

produced thanks to a more accessible public training system. The costs include expenses of

operating the TAFE system allocated to governments, students, and employers. After

comparing these costs and benefits of the TAFE system, the final section provides a

concluding discussion of policy implications arising from these findings. A technical appendix

provides more details regarding several of the methodological issues confronted in the cost-

benefit analysis.

The Economic and Social Benefits of the TAFE System 11

The Crisis of Australian VET Policy

Strong vocational education and training (VET) systems are vital to the success of dynamic,

innovative economies and inclusive labour markets. Australia’s VET system once provided

well-established and dependable education-to-jobs pathways, but a combination of policy

mistakes and fiscal mismanagement plunged the VET system into a lasting and

multidimensional crisis. A recent index comparing education systems and labour market

outcomes across 80 countries ranked Australia’s VET system, once the envy of the world, as

20th. For mid-level skills capability, the ranking was even lower: 38

th

in the world (Lanvin &

Monteivo, 2020).

3

Multiple policy failures produced this outcome:

• Both state/territory and Commonwealth levels of governments have failed to

provide adequate long-term fiscal support to vocational training, with post-

secondary education expenditures increasingly focused on the university sector.

• A policy experiment in establishing a ‘contestable market’ for vocational education

services that decentralised offerings, course delivery and student recruitment to

unaccountable for-profit training providers also failed. Poor-quality programs and

providers proliferated, with the result that VET skills coordination and planning is in

disarray.

• Enormous public subsidies for private VET providers were introduced under the

poorly controlled VET FEE-HELP loans system—introduced first in 2007, and then

expanded in 2012 through demand-driven arrangements. The VET FEE-HELP loans

regime wasted public resources, and spurred unethical and unproductive practices in

the for-profit VET system. At the same time that up-front fees for VET courses were

introduced, Commonwealth funding for university enrolments was uncapped. When

coupled with the existing HECS-HELP regime (which allows for full fee deferral),

vocational education was effectively discouraged—even for those students for

whom vocational education was better aligned with their skills and interests. The

unequal funding treatment between post-secondary funding regimes continues to

distort higher education decision-making by young Australians.

• Despite the government’s own 2016 review into VET, which recommended fee caps

and tighter regulation (Department of Education and Training, 2016), the

Productivity Commission’s (2020b) interim report on national VET reforms

3

Other indications of access and mobility problems in Australia’s education-to-jobs system are low rankings

for matching labour market demand to workforce supply (ranked 17

th

), the provision of lifelong learning

(14

th

), and access to growth opportunities (14

th

).

The Economic and Social Benefits of the TAFE System 12

responding to the COVID-19 crisis has worryingly recommended the same policies

that landed the sector in hot water before the pandemic. Measures recommended

by the Productivity Commission include uncapping fees, expanding access to student

income-contingent loans, and replacing direct public subsidies to providers with a

student voucher system. These policies would reinforce the failure of previous

market-driven models.

• While experimenting in marketisation, most state/territory governments and the

Commonwealth Government ruthlessly cut the budgets of the public TAFE system—

Australia’s longest-standing, quality, publicly accountable core provider of vocational

education. Consequently, the TAFE system’s vital ‘anchor’ function as a high-quality

public institution – working in cooperation with industries, and embedded in

communities – is in jeopardy.

REDUCED ENROLMENTS

After a short-lived surge in enrolments once VET FEE-HELP was extended across the sector,

program enrolments in vocational training (including apprenticeships and traineeships) have

fallen sharply. Eligibility criteria and oversight were tightened in 2015–16 in response to

numerous scandals (and VET FEE-HELP was replaced by the new VET Student Loans

Scheme

4

). However, without any corresponding commitment to resource more genuine VET

streams as alternatives to dodgy for-profit providers, this only reinforced the enrolment

decline.

This failure to seize the opportunity to repair the damage of marketisation during the 2015–

16 government VET review has seen the number of program enrolments begin to decline

precipitously – and that decline has accelerated during the COVID-19 pandemic. Table 2

shows that program enrolments across the total VET sector declined by around 450,000

between 2015 and 2018. By number of enrolments, the decline has been highest for private

training providers and for TAFE institutes; but as a proportion of previous enrolments, the

decline has been experienced broadly across most providers. TAFE institutes broadly

maintained their 32% share of all VET enrolments from 2015 through 2018.

4

The Commonwealth Government implemented the VET Student Loans program on 1 January 2017, replacing

the existing VET FEE-HELP scheme for new students. The new VET Student Loans provide eligible students

with an income-contingent loan to pay their tuition fees for VET qualifications at the Diploma level and

above. Like university HECS loans, students are only required to repay loans when their income after

graduation exceeds a minimum threshold.

The Economic and Social Benefits of the TAFE System 13

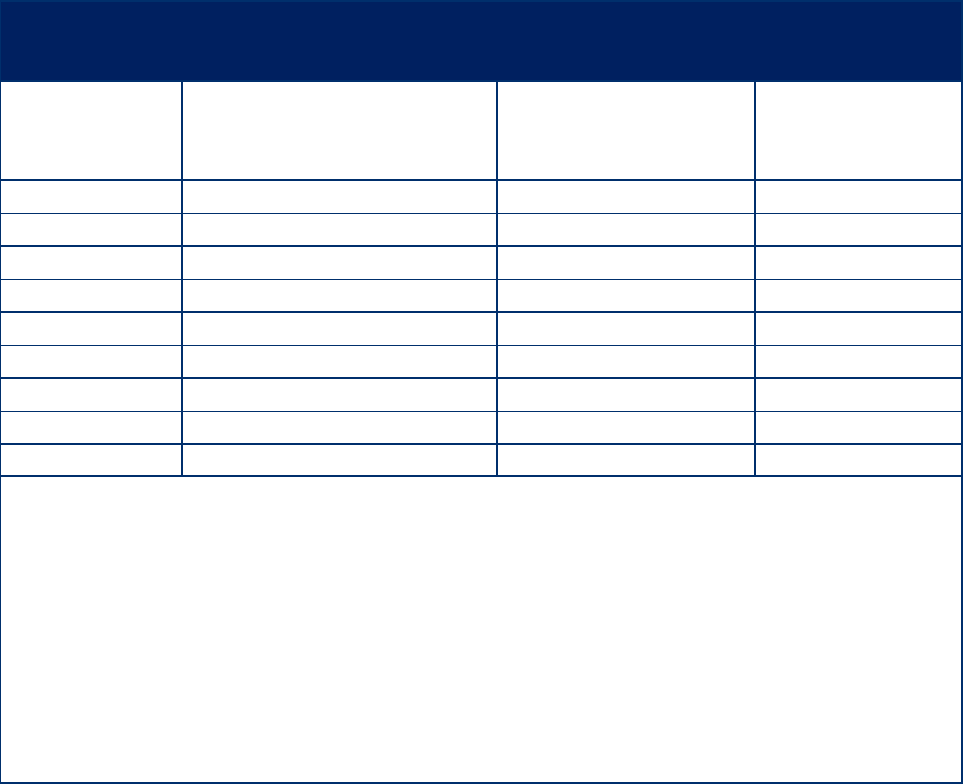

Table 2

Program Enrolments by VET Provider (2015–18)

Provider Type

2018

Change

2015–18

% of all

Enrolments

2015

% of all

Enrolments

2018

Private Training

Providers

1,391,359

–260,592

54%

53%

TAFE Institutes

833,134

–155,806

32%

32%

Enterprise Providers

83,851

–2618

3%

3%

Community Education

Providers

102,488

+845

3%

4%

Schools

144,090

–32,135

6%

5%

Universities

67,602

–7148

2%

3%

Total

2,622,523

–457,455

100%

100%

Source: NCVER, 2018.

Apprenticeship and traineeship positions have been another casualty of the Australian VET

system crisis—falling dramatically since 2012. Figure 1 shows that the number of

apprentices and trainees in training plunged by almost half after 2012, to just 275,000 in

2017. That decline levelled off and recovered just slightly; but there were only 5000

additional apprentices and trainees in training by June 2019. However, even that modest

growth was subsequently lost because of the severe impacts of the coronavirus crisis on

employment and recruitment. The Mitchell Institute (2020) predicts a further 30% drop in

new apprenticeships (representing a further decline of 130,000 fewer apprenticeships) from

the virus shutdowns through to 2023. That comes on top of the pre-pandemic decline of

more than 200,000 apprentices and trainees removed from the skills pipeline compared

with 2012 levels. If the Mitchell Institute forecast is realised, total apprenticeship and

traineeship numbers will have declined by 70% since 2012.

Since the TAFE system is the dominant provider of apprenticeships and traineeships—

delivering around half of all government-funded programs in 2018

5

—it is not a coincidence

that Australia’s crisis in apprenticeship numbers has coincided with funding cuts to TAFE.

Apprenticeships require long-term investment and commitment from both the apprentice

and the employer. The OECD (2010, p. 49) acknowledges that this relationship is best

established through public funding arrangements, since VET skills yield wide returns to

employers and the economy, and pure market models cannot adequately reflect these

returns in course fees to students. As a result, without public funding all actors suffer

through under-provision of skills.

5

‘Government-funded programs’ refers to all Commonwealth and state/territory government-funded training

delivered by technical and further education (TAFE) institutes, as well as by other government providers

(including universities), community education providers and private training providers.

The Economic and Social Benefits of the TAFE System 14

Figure 1. Total Apprentices and Trainees in Training, 2005–19.

Source: NCVER, Apprentices and Trainees (June 2019). Annual averages.

Indeed, the establishment of private market principles for VET delivery and the VET FEE-

HELP scheme increased both the cost of education for individuals (many of whom could not

afford the new fees) and the employer risk (and costs) of investing long-term in their future

workforce. This retreat of government from vocational skills and training has reinforced

limited-horizon, more apprehensive attitudes among employers, who now invest less in

workforce training and skills—particularly given the context of increased competition and

access to an abundant supply of underutilised labour. An Australian Industry Group (AiG

2018) survey of firms employing a total of over 110,000 employees found that only half

these firms planned to increase training expenditure in future years. The same survey

reported that employers are facing stubborn skills shortages, particularly in trades and

technicians.

Decline in VET training programs has occurred alongside continued growth in the overall

workforce—and the associated demand to expand training provision. Expressed as a share

of total employment, the decline in apprentices and trainees in training has been even more

severe. Figure 2 illustrates the decline in the overall rate of vocational education undertaken

across the Australian economy from 2012 to 2019 (before the pandemic struck). In 2019,

total participation in apprenticeships and traineeships represented only 2.1% of Australian

employment—just half the 2012 rate. This constitutes one of the weakest vocational

education participation rates of any industrial country.

The Economic and Social Benefits of the TAFE System 15

Figure 2. Apprentice and Trainee Training Rate, 2005–19.

Source: Author’s calculations from NCVER, Apprentices and Trainees (June 2019) and ABS

Catalogue 6202.0. Annual averages.

REDUCED FUNDING

The combination of reduced funding for public VET education and the introduction of VET

FEE-HELP triggered a damaging cycle of cumulative causation: reduced enrolments allowed

government to further cut funding, thereby both reducing course offerings and the quality

of vocational training, which further reduced the standing of the TAFE system among

students and employers, and discouraged enrolments even further.

Figure 3 presents ABS annual data on government spending by education sector for the

financial years 2005–06 to 2017–18.

6

The data provide total operating expenditure on

education and training by Commonwealth and state/territory governments, and

6

Data for the last four financial years from ABS 5518.0.55.001 provide government expenditure figures under

the following classifications: ‘school’, ‘tertiary’ and ‘other education’ only. The VET and university sectors are

combined under ‘tertiary education’. We calculate a proxy for VET expenditure from the ‘Control n.f.d.’

sector which represents expenditure on public universities (e.g. tertiary education – Control n.f.d = VET).

However, this figure does not include state–Commonwealth consolidations. This may explain why our final

funding figures are higher than those reported in other studies utilising the same ABS catalogue (e.g. Pilcher

and Torii, 2017). In addition, we report figures in real 2017–18 (Australian) dollars. Nominal data have been

converted to real terms using the ABS State and Local Government Final Consumption deflator.

The Economic and Social Benefits of the TAFE System 16

expenditure of public entities including government schools, TAFE institutes and public

universities. All spending from public funds by private providers is included.

Figure 3. Real Government Funding by Sector (2005/6 to 2017/18).

Source: Author’s calculations from ABS Catalogue 5518.055.001, Table 2. Figures adjusted to

2018 dollars.

The figures show that government VET spending has languished far below funding for

schools and universities over the last decade, declining by 1% in real terms since 2005–06 to

only $6.9 billion in 2017–18. Over the same period, real spending on primary and secondary

schools increased by 23% from $42.7 billion to $52.9 billion—consistent with the growth in

everyday operating costs due to both increasing student numbers and improved per capita

spending (Pilcher & Torii, 2017). Meanwhile, government expenditure on universities

increased the most of all education sectors, with a total $30.2 billion spent in 2017–18—

more than 45% above 2005–06 levels (in real terms). University spending growth escalated

from 2012, when the government introduced uncapped funding based on enrolments—the

same year that the VET FEE-HELP loans system was introduced. These contradictory policies

have led to stark funding divergences between VET providers and universities, reflecting the

failure of policy makers to create a more coherent and balanced tertiary education system.

Calculating total government expenditure per enrolment by sector paints an even starker

picture of funding inequities between universities and VET providers in tertiary education

(as indicated in Table 3). Government spends just $6,479 per year per full-time equivalent

The Economic and Social Benefits of the TAFE System 17

(FTE) VET enrolment, compared to $40,495 per year per FTE enrolment for universities,

7

and

$13,574 per year for each primary and secondary school enrolment. This gross imbalance in

government funding to VET hinders Australia’s ability to deliver high-quality vocational

education and to prepare for future jobs.

Table 3

Government Funding Per Enrolment by Sector (FTE)

(2017/18)

Total FTE Enrolments

Funding Per FTE

Enrolment ($)

VET

1,070,735

$6,479

Schools

3,893,834

$13,574

University

746,093

$40,495

Source: Author’s calculations from ABS Catalogues 5518.0.55.001, Table

2, and 4221.0; Department of Education and Training, uCube; NCVER,

Total VET Students and Courses.

School enrolments combine government, catholic and private schools.

TAFE SYSTEM ERODED

The past decade of failed policy experimentation in VET delivery has decimated the TAFE

system. The number of TAFE providers has been cut by almost 40% within the last five years

alone—only 35 TAFE providers remain nationally.

8

TAFE institutes once functioned as

‘anchors’ of the VET system: a network of stable, well-funded, publicly accountable and

trusted institutions that provided a full range of vocational courses (including course

offerings considered too unprofitable to deliver in the private sector). The TAFE system

oversaw most apprenticeships, and it innovated new curriculums and teaching methods. In

1996, 83% of students undertaking publicly funded VET were registered at TAFE institutes

(NCVER, 2018).

In contrast, from the late 1990s, Australia began instituting training market-oriented policies

to complement the wider neoliberal push for labour market deregulation. The introduction

of the ‘User Choice’ policy in 1998 marked the official emergence of a newly minted market

system for VET (Toner, 2018), whereby TAFE institutes were supposed to compete with

private providers on the ‘same ground’ for (publicly subsidised) student dollars. In 2008,

Australian governments made all public VET funding ‘contestable’. Numerous systems were

7

Government spending per FTE university enrolment has not been adjusted for HECS loan repayment.

8

The number of TAFE providers nationally has declined from 53 in 2014, to only 35 in 2018 – a 39% reduction

in TAFE institutes (Table 5A.7; Productivity Commission, 2020a).

The Economic and Social Benefits of the TAFE System 18

introduced to price and allocate public training funds, including tendering processes,

voucher systems and uncapped pricing under the VET FEE-HELP scheme.

However, decades of delivering a full infrastructure of public vocational education left the

TAFE system with ongoing fixed and operating costs that private providers did not incur

(including infrastructure, capital projects and the maintenance of industry and schools

partnerships). Some private providers developed gimmicky marketing schemes (for

example, offering ‘free’ iPads for new students that were, of course, hidden within tuition

costs), and poorly designed and delivered courses proliferated nationally. TAFE institutes

were stranded, while public resources flowed to private VET provision. This forced the cash-

strapped TAFE system to pare back offerings, further undermining its standing among

students and employers as a reputable and stable skills provider. By 2018, only 61% of

government-funded VET students were enrolled in TAFE institutes (NCVER, 2018).

Wheelahan (2018) reports that the total hours of training offered by TAFE institutes

nationally fell by 30% between 2009 and 2016, compared with a near-doubling of hours

provided by private providers over the same period.

Figure 4. Reductions in TAFE Staff Levels by State 2012–19 (FTE).

Source: Author’s calculations from various consolidated TAFE annual reports and state

education system workforce profiles. Due to restricted data availability, starting point for

Tasmania and Qld is 2014, and 2013 for SA. All other jurisdictions from 2012. 2018 latest

data available for Victoria and ACT. No state-wide data available for WA and NT.

Alongside these falling enrolments and budget cuts, staffing levels in the TAFE system have

fallen sharply. As illustrated in Figure 4, almost 10,000 FTE TAFE positions have been cut

The Economic and Social Benefits of the TAFE System 19

since 2012 across six states and territories.

9

The two largest TAFE systems—Victoria and

NSW—have been the worst hit, with nearly 9000 FTE positions cut just from these states.

Not surprisingly, an environment of job cuts and restricted funding leads to increased

pressures on TAFE employees. A recent survey of TAFE employees by the Australian

Education Union (2020) confirmed increasing workload pressures across all teaching levels.

The average TAFE institute teacher is now performing an additional day of work per week

unpaid; and 93% of respondents reported that the pace or intensity of their work had

increased since 2016.

9

Figure 4 includes those 6 states and territories which publish TAFE workforce data.

The Economic and Social Benefits of the TAFE System 20

The COVID Recession, Jobs and Skills

The retreat of public-funded VET will make it all the harder for Australia’s labour market to

respond to the major employment shocks precipitated by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Deliberate shutdowns of large sections of the economy to protect public health have caused

an unprecedented economic crisis. The resulting economic contraction is faster and deeper

than the Depression of the 1930s, with falling employment, GDP, incomes and tax revenues.

The pandemic has certainly shocked the labour market, with true unemployment rising far

beyond what official ABS figures indicate. Official unemployment rose to above 7% in the

first months of the recession—a very serious level. However, if we include those who were

‘employed’ but who did not work any hours, those who did not actively seek work (and thus

were considered outside of the labour force), and the equivalent loss of jobs resulting from

the steep decline in average hours lost across the workforce (on a FTE basis), an effective

unemployment rate of around 20% is indicated.

10

Young workers have been hardest hit by the shutdowns, due to their heavy employment in

vulnerable customer-facing service sectors like retail, hospitality and personal services.

Between March and April 2020, hours lost for young workers aged 15–24 were double that

of older age groups, and their participation rate declined by 6% compared to 2% for workers

aged 25–54 (Borland, 2020). But employment outcomes had already been worsening for

young workers since the GFC. More than 600,000 people aged 15–24 were not ‘fully

engaged’ in either employment or education in 2019 (defined as being either in full-time

education or employment or in part-time combinations of both). This is an increase of over

130,000 from 2007.

11

Earnings lost from young people’s time out of employment, education

or training are estimated at 1% of GDP (or over $16 billion per year in 2016; OECD, 2016).

The pandemic will only increase youth dislocation. Through failure to harness a generation

brimming with skills and capacity, COVID-19 will also increase the costs of long-term youth

unemployment on young people’s lives, their families and the wider economy. Despite the

dire need for sustained public investment to generate jobs in the crisis, the Commonwealth

Government has yet to commit to any generalised or targeted long-term jobs-generating

measures.

Another major trend impacting skills and employment, and that will be accelerated by the

pandemic, is the rapid change in the composition of Australia’s business community. Recent

years have witnessed the loss of thousands of medium and large firms. ABS firm data show

that there are 20,000 fewer medium-sized firms (employing 20–199 people), and over 2000

10

Author’s calculations from ABS Catalogue 6202.0.

11

From ABS Catalogue 6227.0.

The Economic and Social Benefits of the TAFE System 21

fewer large firms (employing more than 200 people), than there were 15 years ago.

12

Meanwhile, more than 5,000 small firms employing less than 20 people, and an astonishing

200,000 micro-firms employing less than five people were created over the same period.

Investment in skills, new capital formation and innovation are all very low in small firms,

since they lack the financial resources and the economies of scale required to invest in long-

term workforce planning. This is why small firms are typically unlikely to have dedicated

training staff of their own (Hawke, 1998), and hence are especially dependent on the

training services provided through a public system. A smaller and weaker TAFE system will

not be able to address the increasingly inadequate training capabilities of Australia’s

growing community of very small businesses.

In sum, the Australian labour market faces a challenging period of structural change in the

years ahead, made all the more treacherous because of the uncertainty regarding

continuation of emergency income supports and wage subsidies (like JobSeeker and

JobKeeper). These structural changes demand institutions that can assist the gathering of

industry-level information on skills demands, as well as deliver training to assist in labour

(re)allocation as the economy tries to regain its footing after the pandemic. The federal

government’s independent National Skills Commission (NSC) established in June to forecast

jobs and skills in rapidly evolving conditions is mandated to address the present dearth of

labour market planning tools operating at the federal level. But initial indications from

government (including its ‘JobTrainer’ program announced in July) suggest that it still

refuses to acknowledge the central role of public VET services, and TAFE in particular, in

improving Australia’s skills system. Indeed, the Prime Minister’s announcement of the new

$2 billion program did not even mention TAFE, and is likely to reinforce the flow of public

monies into private VET providers.

13

However, government has an historic opportunity in this pandemic to strengthen skills–jobs

planning by building on the essential role that TAFE institutes already play in labour market

planning and coordination. In each state, TAFE institutes work collaboratively with

government, industry and other educational institutions (including schools and universities)

to forecast future skills needs and to align program offerings to meet that demand.

Collaborative and flexible linkages are driven by the TAFE system’s public commitment to

skills and education, and these linkages can support government both to deliver on its

investments and to support employers by nurturing job clusters aligned to identified growth

areas in Australia’s recovery.

12

Author’s calculations from ABS 8165.0 Counts of Australian Businesses, including Entries and Exits. Table 13.

13

Prime Minister of Australia (2020).

The Economic and Social Benefits of the TAFE System 22

Review of Published Research

Economic Benefits of TAFE Institutes

There are no existing studies on the national economic impacts of the TAFE system. KPMG

(2018a, 2018b) has measured the benefits of TAFE institutes at the level of individual state

economies (Queensland and Victoria). Our study is the first national study to include the

Commonwealth costs and benefits of delivering TAFE, and to include the impacts of TAFE for

federal revenues and fiscal outlays for welfare and public healthcare.

KPMG’s Queensland TAFE study uses general equilibrium modelling to measure the

economy-wide impacts of TAFE operations. The study identifies several key economic

benefits from the TAFE system, including a wage premium to people with TAFE

qualifications of $529 million,

14

improved employment outcomes worth $600 million, and

international exports (purchased by foreign TAFE students) of $134 million (all figures

annual). KPMG find that for an investment of $707 million in TAFE Queensland in 2017, the

total economic value realised to the state’s economy was some $1.8 billion. Hence, for

every $1 spent, a total of $2.55 value-added is created.

KPMG use the same methodology for a parallel study of the social and economic benefits of

the Victorian TAFE system. They find that Victoria’s TAFE institutes generated $2.9 billion

per annum in Gross State Product (GSP) from higher workforce participation and earnings,

along with additional economic demand generated by these improved labour market

outcomes, by the TAFE system’s direct operations, and by international export

contributions. For every $1 spent on Victorian TAFE, the TAFE institutes returned $2.19 to

the state economy.

Cost-benefit studies for vocational education and other education systems

A range of cost-benefit studies have considered the economic impacts of broader education

systems. For example, Birch et al. (2003) conduct a comprehensive cost-benefit study of the

adult and community education sector in Australia. They adopt a human capital model to

develop estimates of economic impacts on individuals (including, for example, course fees

and deferred earnings) and on communities (for example, income to the sector’s providers,

14

It should be noted here that the KPMG methodology uses a different approach to estimating the value of

higher wages resulting from TAFE training, from the one we utilise in the discussion below. The KPMG model

estimates the value of higher wages accruing only to those workers who graduate TAFE in the specific

reference year considered, in order to generate a flow of benefits that can be associated strictly with the

costs invested in TAFE for that same year, and thus calculate a return on that year’s public investment. In

contrast, we measure the aggregate annual wage benefits resulting from the historic accumulation of TAFE-

provided skills in the workforce at the present time; this flow of benefits is much larger than the narrower

conception considered by KPMG.

The Economic and Social Benefits of the TAFE System 23

wages and salaries, additional tax revenues). Three scenarios are adopted, with the ‘most

likely’ returning net community and private labour market benefits exceeding $3 billion.

Multiple studies of early childhood education demonstrate the net economic benefits of

investing in public childcare. These studies develop additional bridging steps in their

methods to trace capabilities developed through education in early years through to higher

education (and then the workforce). PwC on behalf of The Front Project (2019) has

conducted the most comprehensive cost-benefit analysis in the Australian context for early

childhood education. They estimate $2 billion in costs for 15 hours of childhood education

for one year before school, compared to $4.8 billion in benefits.

15

This produces a benefit-

cost ratio of $2 in benefits generated for every $1 spent.

Some studies report cost-benefit analyses for workplace-integrated education and training

through apprenticeships. The Centre for Economics and Business Research (CEBR) in the UK

(2014) measures the wage premium by taking the total number of jobs requiring

apprenticeships, quantifying total earnings in these jobs, and comparing to earnings in

counterfactual jobs that do not require apprenticeship completion for entry. They find

economic gains in higher wages, productivity and government revenues totalling £31 billion

per year. Higher employment levels reduce government expenditure on unemployment

benefit payments by £370 million per year, and benefits to organisations while training

apprentices in reduced wages bills are worth an additional £2 billion per year. For each £1 of

public money spent, apprenticeships generate an additional £21 for the national economy.

The Conference Board of Canada (2019) develops two main benefit ‘streams’ for calculating

the economic benefits and costs of high school education completion. The first model

captures the economic footprint of high schools as economic actors in their own right—

including direct, indirect and induced economic impacts. The sum of all these effects

represents the overall impact of the sector’s economic footprint. They find that, including

indirect and induced impacts, a 1% increase in public education spending in Ontario

supports around 4200 additional jobs. An increase in fiscal spending on education of 1% (or

an additional CA$291 million in spending on education services) leads to an additional

CA$371 million in economic activity—demonstrating an economic multiplier of 1.3-to-1.

The second Conference Board stream uses a scenario approach in three areas of

government spending—social assistance, healthcare and criminal justice—to quantify the

fiscal savings from raising the high school graduation rate. They identify annual cost savings

of CA$5 million in social assistance (and a cumulative saving of CA$1 billion to 2040);

CA$6 million in annual savings for public healthcare (or CA$1 billion in cumulative savings to

2040); and CA$5 million in reduced annual criminal justice spending, compounding to

another CA$1 billion in aggregate savings.

15

The study discounts long-run future benefits at 3% per year.

The Economic and Social Benefits of the TAFE System 24

Our study considers both of these ‘streams’ (the economic footprint of the education

system’s operation, and the fiscal savings arising from improved life chances for graduates)

in assessing the economic impacts of TAFE.

Higher wages and employability

There is a significant body of academic and policy literature demonstrating the strong

earnings and employment returns to VET. A UK study by Conlon and Patrignani (2013) find

an earnings premium associated with completing VET of 2–4% per year in the workforce for

seven years post-qualification attainment, and a 3–4% increase in the probability of

employment.

Several international and Australian studies have estimated the earnings returns to

vocational education, typically by comparing the earnings of VET graduates with those of

Year 12 or below–Year 12 earners. For example, a recent Australian study on returns to

education by Gong and Tanton (2018) uses Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in

Australia (HILDA) survey data to assess the returns to post-school qualifications compared

with Year 12 between 2006 and 2016. No wage premium to vocational education compared

with Year 12 is identified (for either males or females). A key limitation of the findings is the

exclusion of self-employed workers (who are typically higher-paid VET qualification-

holders). Moreover, a comparator of Year 12 alone is less relevant to measuring the benefits

of VET qualifications, for several reasons: including that many students enter VET without

having completed Year 12. A more appropriate baseline to measure the impacts of VET

would include school leavers and the unemployed. This is confirmed by the significant

negative wage premium identified for not finishing Year 12 of around 10% for males and 8%

for females.

Long and Shah (2008) assess returns to VET compared with a composite group of workers

whose highest level of schooling was Year 12 or below. Incomes of the self-employed, as

well as the unemployed, are included. Confirming that VET is an important pathway for

school leavers, the study finds that rates of return to VET are higher for those whose highest

school qualification was Year 10, as compared to Year 12 (particularly for females). The

study finds that the individual return on investment for males undertaking Diplomas or

Certificates III/IV and for females undertaking Diplomas exceeds 20% for full-time study.

16

Rates of return increase greatly for part-time students, due to lower forgone earnings.

Leigh (2008) also identifies significant individual returns to vocational education, and

describes the source of returns: around one-third of the gains arise from higher

productivity, and two-thirds from higher labour force participation. Compared with an

educational attainment of Year 11 or below, Wilkins and Lass (2018) find a 25% wage

16

Individual return on investment is the additional income earned through the VET qualification, minus the

costs of enrolling in VET courses, which include course fees, income forgone while studying, non-completion

costs, and impacts of subsidies on individual VET course outlays.

The Economic and Social Benefits of the TAFE System 25

premium to Certificate III/IV-holding males (but no significant premium for females), and a

39% and 14% premium to Diploma- and Advanced Diploma-holders among males and

females, respectively.

17

One international study on increased female labour force participation due to access to low-

fee childcare in Quebec, Canada, is useful for the present study’s assessment of increased

employability (Fortin et al., 2018). The authors estimate that an additional 70,000 women

entered the workforce due to enhanced childcare access, raising total employment by 1.7%

and GDP by CA$5 billion. This influx of new wage incomes and GDP returned an estimated

CA$2 billion in government revenues and social assistance savings, far exceeding net

expenditure of CA$2 billion on the enhanced access program—showing that this policy

literally more than paid for itself.

Additional productivity benefits

Once the wage and employment returns associated with holding a particular qualification

are calculated, the productivity gained by the qualification can be estimated. Some studies

assume that returns to educational qualifications reflect the individual worker’s marginal

productivity (for example, KPMG 2018a, 2018b). Hayward et al. (2014) vary this assumption,

allowing for productivity increases greater than wages, recognising that if the productivity of

an individual were not greater than their cost, employers would lack an incentive to employ

that individual.

A longitudinal UK study by Dearden et al. (2005) finds that only half of the benefit of training

accrued to the individual in higher wages; the rest was captured by employers and/or

consumers through enhanced profit share and/or lower output prices. This finding is

consistent with Australian research, which has identified a long-term decline in labour’s

share of total national income, as well as a weaker relationship between wages and labour

productivity.

18

In that context, the productivity benefits of vocational education cannot be

proxied by a wage premium alone.

Education and health

There is substantial international and Australian evidence of strong links between education

and health outcomes. This is partly explained by an observed correlation between education

and health determinants—such as risk taking, smoking, and using (or not using) preventive

services (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2019; Feinstein et al., 2006). A UK study

17

The absence of a wage premium for full-time employed women holding Certificate III/IV qualifications

compared to Year 11 and below reflects entrenched low-wages environments that are typical of the

undervalued feminised industries into which these qualifications provide entry, such as healthcare and

community and social services.

18

See, for example, Flanagan and Stilwell (2018) and the research referenced therein.

The Economic and Social Benefits of the TAFE System 26

finds that individuals with higher vocational degrees were less likely to visit the GP than

individuals with no post-school qualifications (Windmeijer and Santos Silva, 1997).

In Australia, Stanwick et al. (2006) find that Australian males whose highest qualification

attainment was a Diploma or an Advanced Diploma were 0.5% more likely to have better

physical health and 1% more likely to have better mental health than those who had

reached Year 11 or below. The Mitchell Institute finds that 42% of male and female school

leavers of working age have a long-term health condition, compared to only 26% of the

general working-age population (Lamb and Huo, 2017).

The Economic and Social Benefits of the TAFE System 27

Costs of the TAFE System

This section outlines the direct costs of delivering the TAFE system in its current (downsized)

condition. Table 4 provides a summary of the various cost categories included in our analysis

for 2018 (these are the most recent data currently available). We have considered all direct

costs of TAFE delivery, including government funding for training and administration,

employer and student assistance, loans and income support payments, student fees, and

employer costs for training apprentices and trainees. We do not include certain indirect VET

costs associated with education, such as tax expenditure (forgone revenues for government)

and opportunity costs (forgone earnings for students).

Table 4

Summary of TAFE Costs Items and Annual Costs

Item

Estimated Annual

Cost (2018)

Government

Total funding (Commonwealth

and state/territory, including

capital costs)

$3.17 billion

Employer assistance

$84 million

Study assistance

$17 million

Administration and governance

$77 million

VET Student Loans and Trade

Support Loans

$243 million

Income support payments

$59 million

Total Government

$3.65 billion

Students

Student fees

$1.13 billion

Employer

Apprenticeship and traineeship

training costs

$934 million

TOTAL

$5.71 billion

Source: Author’s compilation from NCVER (2019c); student fees across

consolidated state/territory figures from TAFE Annual Reports 2018–19 for

NSW, ACT, South Australia and Queensland; WA from Office of Auditor General,

Appendix 3: Universities’ and TAFEs’ expenditure and sources of revenue.

Apprenticeship costs derived from ABS 6306.0 (see Footnotes 26-27).

Where specific TAFE institute data were available, this was utilised in our analysis. Where

disaggregated data by VET provider type were not available, our estimates of TAFE institute

costs were based on the TAFE system’s share of all VET students in 2018 (including private

providers), or on the TAFE institutes’ share of all students undertaking vocational education

The Economic and Social Benefits of the TAFE System 28

with public providers. All student population data are sourced from NCVER. Each cost item

has been calculated on an annual basis.

TAFE Delivery and Administration

NCVER (2019c) collates data on total government funding for Australian VET including

funding allocations across Commonwealth and state/territories. Certain funding activities

can be split by provider type, including private, public and other categories. ‘Public’ provider

funding includes total government funding for VET activities to TAFE institutes, skills

institutes, polytechnics and universities. Total VET provider-level figures include funding for

VET delivery (all funding for the delivery of training outcomes, including operational/base

and block funding, and subsidies targeted at supporting access), as well as capital funding

(major capital projects and acquisitions to host VET training). Using NCVER total VET student

data, we estimate the TAFE system’s share of VET students studying within public providers

(92%) and then scale the total public VET funding for 2018 by the TAFE student share. The

total annual cost of TAFE VET delivery (including capital costs) is thus estimated at

$3.2 billion.

Other funding activities reported separately in NCVER’s government funding inventory (and

not included in the funding by provider data) relevant to the costs of TAFE delivery include

employer assistance, student assistance, and system administration and governance

funding. The proportion of these total VET costs attributed to TAFE institutes is calculated

based on their 14% share of total VET students in 2018. Note that:

• Employers receive government assistance to engage in VET, including funding for

workforce training, and incentives to take on apprentices and trainees. General

assistance for employers to engage in VET information and administrative support

includes tax exemptions, offsets and rebates. The total annual cost of employer

subsidies for TAFE students is estimated at $84 million.

• Students receive assistance for equipment, travel and other non-tuition costs

associated with undertaking VET study. Student assistance funding includes loans,

grants and subsidies to VET students. The proportion of this student assistance

flowing to TAFE students is estimated at $17 million.

• The costs of administering the national VET system, including supply and services,

and of employee expenses within each jurisdiction’s VET portfolio (including direct

administration and governance costs of the providers, including TAFE institutes) are

captured within the cost of system administration and governance of TAFE institutes.

This is estimated to be $77 million.

The Economic and Social Benefits of the TAFE System 29

Student Loans

Student loans represent additional costs within the TAFE system delivery. The

Commonwealth Government provides funding for two income-contingent loan schemes:

the VET Student Loans program (which includes grandfathered VET FEE-HELP loans) and the

Trade Support Loans Scheme.

19

Government provisions for VET loans are presented

separately in NCVER’s government funding tables. NCVER reports the total VET Student

Loan amount in the reporting year, rather than the ultimate net costs to government of

administering the loans. Actual costs would account for repayment of most of the loans over

a given period of time.

20

Given the lack of government data on actual VET Student Loan costs by provider type (public

and private providers), and the ambiguous status of government financing of VET loans

(such as a 2019 decision to absorb $500 million in ‘dodgy debts’ associated primarily with

private providers), we elect to use NCVER’s total loan amount figures as proxies for

government student loan costs. The cost of all income-contingent VET Student Loans to

TAFE students is calculated as a proportion of all VET Student Loans paid to students

enrolled at public institutions. The TAFE institutes’ proportion of public loan costs is based

on their 2018 share of all public students (92%).

21

The total cost of income-contingent VET

Student Loans to TAFE students is therefore $175 million.

Eligible apprentices can apply for assistance with the costs of living and learning through the

Trade Support Loans Scheme. Loans of up to $21,078 for eligible apprentices are distributed

over four years (Commonwealth Government, 2019). The total cost of Trade Support Loans

to TAFE students is calculated based on the TAFE system’s share of apprentices and trainee

students in the VET system in 2018 (32%). The estimated annual cost of Trade Loans to TAFE

students is therefore $68 million.

22

19

While the Commonwealth is the main funder of income-contingent loans, states and territories contribute

50% to the cost of loan debts not expected to be repaid by government-funded students. These payments

are transferred from states and territories to the Commonwealth each year. In 2018, the value of these

transfers was $8.5 million (NCVER, 2019c).

20

NCVER’s loans reporting includes the value of grandfathered VET FEE-HELP ‘dodgy debts’ (in addition to new

loans made under the new VET Student Loans). As stated above, government has elected to absorb at least

$500 million of these debts in 2019, indicating that total loan amounts would still be acceptable indicators of

government loan costs to students of private providers until the new loans system applies and the sector

recuperates.

21

TAFE institutes are the dominant provider of government-funded VET however there are a smaller number

of other government providers including community education providers.

22

This estimate does not include the smaller Living Away From Home Allowance (LAFHA) program, which is a

weekly payment to apprentices starting at $77.17 each week in the first year of the apprenticeship. Payments

reduce to $25 each week in the third year.

The Economic and Social Benefits of the TAFE System 30

The total cost of income-contingent loans to TAFE students and apprentices totals to $243

million: $175 million for VET Student Loans and $68 million for Trade Support Loans.

Student Income Support Payments

Many TAFE students can receive additional income support while undertaking study. Study

allowance and support payments considered in our calculation include:

• Youth Allowance (which is the primary income support payment for full-time

students and apprentices aged 16–24)

• Austudy (which is a separate income support program for students who commence

full-time studies or training when they are 25 years or older)

• ABSTUDY (which is a specifically designated income support payment to Indigenous

students in secondary and post-school education).

According to the most recent available data on Youth Allowance payments to students and

apprentices by sector from the Department of Social Services, the vast majority (78%) of all

payments at June 2016 went to students in higher education. A further 14% of recipients

were undertaking VET, while 5% were undertaking schooling and 2% apprenticeships (and

1% were unspecified).

23

The combined total income support share relevant to the VET

sector is 16% (including VET and apprenticeships) (Department of Social Services, 2016)

Meanwhile, Department of Education and Training higher education data show that the

proportion of domestic students enrolled full-time (a criteria for Youth Allowance student

payment eligibility) in university education has remained steady from 2016–18 (Department

of Education and Training, 2017). The number of VET students studying full-time declined by

10% between 2016 and 2018 (NCVER, 2018b). We assume that these changes to full-time

rates have had a negligible impact on 2016 income support payment data. We also assume

that Austudy and ABSTUDY payments are distributed across sectors in the same proportions

as Youth Allowance.

Total government spending on Youth Allowance, Austudy and ABSTUDY was $2.6 billion in

2018.

24

We first estimate that 16% of that total income support spending was received by

VET students (including apprentices). We then calculate the TAFE system’s share as a

23

The Department of Social Services produces two Youth Allowance payment trends reports: (1) all Youth

Allowance income support payments paid to young people who are seeking paid work and undertaking

activities (like study and training) to improve employment prospects; and (2) Youth Allowance payments to

students and apprentices. We refer to data on payments to students and apprentices only. Most of the

recipients of this payment are university students, since they are more likely to undertake study on a full-

time basis (which is a requirement for payment eligibility).

24

2018 Actuals. From Budget 2018–19, Department of Social Services Budget Statements, Table 2.1.2: Program

components of Outcome 1.

The Economic and Social Benefits of the TAFE System 31

proportion of all VET students in 2018 (14%). Annual government spending on income

support to TAFE students is therefore estimated at $59 million.

Student Fees

Most VET providers (including TAFE institutes) charge students fees for the administration of

courses, for tuition, and for the provision of materials and amenities. These fees vary

according to the type of course and its duration as well as the institution providing the

course. Table 5 presents the annual costs of student fees by each state and territory.

Consolidated annual reports for all TAFE institutes operating within the jurisdiction were not

available for Victoria or Northern Territory. For these jurisdictions, NCVER student data for

full-year training equivalent students were utilised to derive estimations of total student

fees.

Table 5

TAFE Student Fees and Other User Charges by Jurisdiction

Total Student Fees and Other