HRSA Health Workforce Training Program

EVALUATION TOOLKIT

Health Workforce Training Program

Evaluation Toolkit

Introduction

The goal of the HRSA Health Workforce Training Pro-

grams is to train clinicians to deliver high-quality care.

This toolkit suggests ways to track trainee outcomes

and your program’s ability to meet the Three Part Aim

goals of improving patient experience and access, low-

ering cost, and raising quality of health care services.

We believe evaluation is the key to the sustainability. As

we build the workforce of the future, it is important that

programs construct evaluations that clearly measure

long-term outcomes on trainees and patients.

Who should use this resource?

This toolkit should be used by the health workforce

grant evaluation planning and implementation team.

Evaluation is best done as a collaborative effort

among stakeholders, including those involved in data

collection and evaluation decisions.

When should it be used?

This toolkit is designed for grantees in the grant-

planning phase and in the evaluation process after a

program award. The toolkit can be accessed by:

1)

Downloading the entire toolkit as a PDF le.

2) Accessing modules individually to address

specic questions, depending on your phase

of evaluation.

Addressing the Three Part Aim Plus Provider

Well Being

HRSA’s funding announcement for the Primary Care

Training Enhancement program states the goal of

“working to develop primary care providers who are

well prepared to practice in and lead transforming

healthcare systems aimed at improving access, quality

of care and cost effectiveness.”

Better

Health

Reduced

Health

Disparities

Lower Cost

Through

Improvement

Better

Care

THREE PART AIM

THREE PART AIM

Reducing

Costs

Provider

Well Being

Patient

Experience

THREE PART AIM PLUS PROVIDER WELL BEING

Population

Health

ADAPTED FROM: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Ofce of the Director, Ofce of Strategy

and Innovation. Introduction to program evaluation for public health programs: A self-study guide. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,

2011. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/eval/framework/index.htm

The National Quality Strategy promoted by the Department of Health and Human Services is an overarching plan

to align efforts to improve quality of care at the national, State, and local levels. Guiding this strategy is the Three

Part Aim which is to provide better care, better health/healthy communities and more affordable care.

1

Recently,

there has been discussion of adding a fourth aim, “provider well being”, which adds improving the work life of

clinicians and staff to the goals.

2

The 2014 Clinical Prevention and Population Health Curriculum Framework, developed through consensus

of educators, created a framework for integration of the Three Part Aim into health professional education.

3

These guidelines acknowledge that going forward more educational content should focus on population health.

Elements of population health have been integrated across accrediting bodies such as the American Association

of Colleges of Nursing and the American Association of Medical Colleges.

The engagement of the health care workforce is of paramount importance in achieving the primary goal of the

Three Part Aim Plus Provider Well Being—improving population health. Health workforce programs should

assess the ways they are preparing future clinicians to provide services that improve patient experience,

population health, cost effectiveness, and provider well-being. This toolkit provides examples for health

workforce grantees to consider as they evaluate the ability of their programs to achieve the Three Part Aim Plus

Provider Well Being.

A note on language

HRSA health workforce programs support a variety of schools and health professionals. Funded programs serve

a range of health professional students and have a wide variety of designs. For this reason, we strive to use

terminology that applies across programs. Throughout this guide the term trainee will be used to apply to the

student or learner regardless of his/her profession or level of education.

1 https://www.amia.org/sites/amia.org/les/Report-Congress-National-Quality-Strategy.pdf

2 Bodenheimer T, Sinksy C. From Triple to Quadruple Aim: Care of the Patient Requires Care of the Provider. Annals of Family Medicine. 2014: 12(6): 573-576.

3 Paterson MA, Falir M, Cashman SB, Evans C, Garr D. Achieving the Triple Aim: A Curriculum Framework for Health Professions Education. Am J Prev

Med.2016:49(2):294-296.

HEALTH WORKFORCE TRAINING PROGRAM EVALUATION TOOLKIT: INTRODUCTION | PAGE 2

INTRODUCTION: Why is engaging stakeholders important to your health workforce

training evaluation?

Stakeholders can help—or hinder—your health workforce training evaluation before it is conducted, while it is

being conducted, and after the results are collected. Stakeholder roles include:

• Responsibility for day-to-day implementation of health workforce training program activities.

• Advocating or approving changes to the health workforce training program that the evaluation

may recommend.

• Continuation and funding or expansion of the health workforce training program.

• Generating support for the health workforce training program.

MODULE 1

Engaging Stakeholders for your

Health Workforce Training Program Evaluation

STEP 1: Who are the health workforce training

program evaluation stakeholders and how do

you identify them?

Stakeholders are all of the people who care about

the program and/or have an interest in what happens

with the program. There are 3 basic categories of

stakeholders:

1. Those interested in the program operations.

2. Those served or affected by the health workforce

training programs.

3. Those who will make decisions based on

evaluation ndings to improve, enhance, or

sustain the health workforce training program.

To identify stakeholders, you need to ask:

• Who cares about the health workforce training

program and what do they care about?

• Which individuals or organizations support the

program?

• Which individuals or organizations could be

involved that aren’t aware of the program?

Use the Identifying Key Stakeholders worksheet listed

in the resources section (example on page 2).

Use the following checklist to involve key stakeholders

throughout the health workforce training program

evaluation process.

Identify stakeholders using the three broad categories

(those affected, those involved in operations, and those

who will use the evaluation results).

Identify any other stakeholders who can improve

credibility, implementation, and advocacy, and make

funding decisions.

Engage individual stakeholders and/or representatives of

stakeholder organizations.

Create a plan for stakeholder involvement and identify

areas for stakeholder input.

Target selected stakeholders for regular participation in

key activities, including writing the program description,

suggesting evaluation questions, choosing evaluation

questions, and disseminating evaluation results.

ADAPTED FROM: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Ofce of the Director, Ofce of Strategy

and Innovation. Introduction to program evaluation for public health programs: A self-study guide. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,

2011. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/eval/framework/index.htm

HEALTH WORKFORCE TRAINING PROGRAM EVALUATION TOOLKIT: MODULE 1 | PAGE 2

PCTE Program example

INNOVATION

Team rounding in the nearby hospital and a special weekly clinic session with medical, pharmacy, and social service appointments for

the recently discharged. The rounding interdisciplinary team will include trainees (medical students, residents, and social work students)

as well as attending physician/preceptors.

OBJECTIVE

Reduce readmissions for high risk patients with multiple chronic diseases, thus decreasing Medicaid spending.

Identifying Key Stakeholders example

CATEGORY STAKEHOLDERS

1 Who is affected by the program?

Medical students

Residents

Health center administration

Social work students

Clinical preceptors

State Medicaid

2 Who is involved in program operations?

Faculty directors and teaching staff

Alumni ofce

Health center administration

Junior faculty/fellows

Senior faculty

Health system leadership

3 Who will use evaluation results?

Program leadership

Clinical training sites

Grants and development ofce

HRSA

Program Partners (i.e. Schools of Social Work)

Peers in the medical education eld

Which of these key stakeholders do we need to:

Increase credibility of our

evaluation

Implement the interventions

that are central to this

evaluation

Advocate for institutionalizing

the evaluation ndings

Fund/authorize the continuation

or expansion of the program

Alumni ofces

Peers in the medical education eld

Clinical preceptors

Faculty

Medical students

Residents

Clinical preceptors

State Medicaid ofce

Program leadership

State Medicaid ofce

Health care system/hospital

HEALTH WORKFORCE TRAINING PROGRAM EVALUATION TOOLKIT: MODULE 1 | PAGE 3

STEP 2: What to ask stakeholders?

You must understand the perspectives and needs of your stakeholders to help design and implement the health

workforce training evaluation. Ask them the following questions:

• Who do you represent and why are you interested in the health workforce training program?

• What is important about the health workforce training program?

• What would you like the health workforce training program to accomplish?

• How much progress would you expect the health workforce training program to have made at this time?

• What are critical evaluation questions at this time?

• How will you use the results of this evaluation?

• What resources (i.e., time, funds, evaluation expertise, access to respondents, and access to policymakers)

could you contribute to this evaluation effort?

The answers to these questions will help you synthesize and understand what program activities are most

important to measure, and which outcomes are of greatest interest. Use the What Matters to Stakeholders

worksheet listed in the resources section to identify activities and outcomes. An example is listed below.

What Matters to Stakeholders example

STAKEHOLDERS What activities and/or outcomes of this program matter most to them?

Medical students/residents Being prepared for residency/being prepared for practice

Alumni ofce Retention and long term engagement of medical students

Program leadership

Retention of medical students

Engaging students in selecting primary care

Exposure of all students to working in underserved settings

Health center administration Reducing unnecessary readmissions

State Medicaid Reducing spending due to unnecessary readmissions

HEALTH WORKFORCE TRAINING PROGRAM EVALUATION TOOLKIT: MODULE 1 | PAGE 4

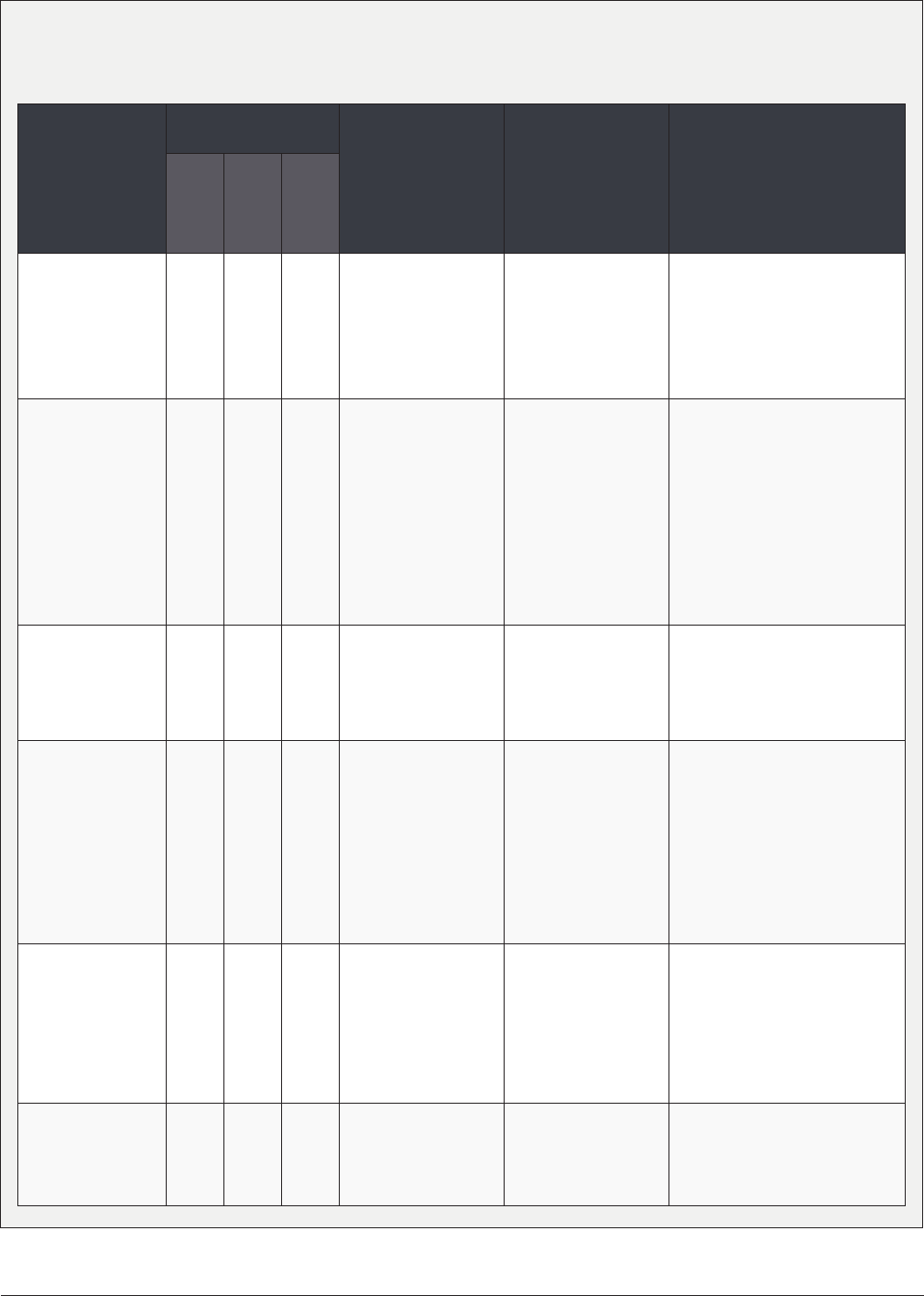

TOOL 1.1

Identifying Key Stakeholders

CATEGORY STAKEHOLDERS

1 Who is affected by the program?

2 Who is involved in program operations?

3 Who will use evaluation results?

Which of these key stakeholders do we need to:

Increase credibility of our

evaluation

Implement the interventions

that are central to this

evaluation

Advocate for institutionalizing

the evaluation ndings

Fund/authorize the continuation

or expansion of the program

HEALTH WORKFORCE TRAINING PROGRAM EVALUATION TOOLKIT: MODULE 1 | PAGE 5

TOOL 1.2

What Matters to Stakeholders?

STAKEHOLDERS What activities and/or outcomes of this program matter most to them?

MODULE 2

Describe the Program

INTRODUCTION: Describe your health workforce training program

The purpose of this module is to fully describe your health workforce training program. You will want to clarify

all the components

and intended outcomes of the health workforce training program to help you focus your

evaluation on the most important questions.

STEP 1: Describe your health workforce training program and develop SMART objectives

Think about the following components of your health

workforce training program:

• Need. What problem or issue are you trying to

solve with the health workforce training program?

• Targets. Which groups or organizations need to

change or take action?

•

Outcomes. How and in what way do these targets

need to change? What specic actions do they need

to take?

• Activities. What will the health workforce training

program do to move these target groups to

change and take action?

• Outputs. What capacities or products will be

produced by your health workforce training

program’s activities?

• Resources and inputs. What resources or inputs

are needed for the activities to succeed?

• Relationship between activities and outcomes.

Which activities are being implemented to

produce progress on which outcomes?

• Stage of development. Is the health workforce

training program just getting started, is it in the

implementation stage, or has it been underway

for a signicant period of time?

Using a logic model can help depict the program

components. Also known as a program model,

theory of change, or theory of action, a logic model

illustrates the relationship between a program’s

activities and its intended outcomes. The logic model

can serve as an “outcomes roadmap” and shows

how activities, if implemented as intended, should

lead to the desired outcomes.

A useful logic model:

• Identies the short-, intermediate-, and long-

term outcomes of the program and the pathways

through which the intervention activities produce

those outcomes.

• Shows the interrelationships among components

and recognizes the inuence of external

contextual factors on the program’s ability to

produce results.

• Helps guide program developers, implementers,

and evaluators.

SMART objectives

As you think about developing objectives within

your logic model, the SMART objectives framework

can help you write objectives that are clear, easily

communicated, and measurable.

The acronym stands for:

S Specic: What exactly are we going to do?

M Measurable: How will we know we have

achieved it?

A Agreed upon: Do we have everyone engaged

to achieve it?

R Realistic: Is our objective reasonable with the

available resources and time?

T Time-bound: What is the time frame for

accomplishment?

ADAPTED FROM: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Ofce of the Director, Ofce of Strategy

and Innovation. Introduction to program evaluation for public health programs: A self-study guide. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,

2011. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/eval/framework/index.htm

Example SMART objectives for

a health workforce training program:

• The program will mentor ve primary care residents’ provision of team-based care over the course of a year. Their team-based

care competency will be measured by a self-assessment tool in months 1 and 12 of the program.

• The program will expose all medical trainees to enhanced competency in social determinants of health including screening for

health literacy and barriers to care; participating in collaborative visits with pharmacists and behavioral health care providers;

and referring to social workers for non-medical barriers. Trainees will be exposed to these approaches in a four-week module

and knowledge of these approaches will be measured through participation in a minimum of ve screenings, ve collaborative

visits, and ve referrals.

STEP 2: Develop a logic model

A useful logic model is simple to develop if you have identied the following information for your health

workforce training program.

• Inputs: Resources crucial to implementation of the health workforce training program.

• Activities: Actual events or actions done by the health workforce training program.

• Outputs: Direct products of the health workforce training program activities, often measured in countable

terms. For example, the number of trainees who participate in a complex care management team meeting

or the number of community providers who participate in population health forums.

• Outcomes: The changes that result from the health workforce training program’s activities and outputs.

Consider including outcomes that measure your program’s success in stages (e.g., short-term: increased

number of trainees who have knowledge of population health management tools; intermediate-term:

increase in patients at clinical preceptor sites who have proactive patient education visits for chronic

disease management; long-term: number of graduates who opt to work in a primary care setting that uses

population health data for patient outreach and screening).

• Stage of development: Programs can be categorized into three stages of development: planning,

implementation, and maintenance/outcomes achievement. The stage of development plays a central role in

setting a realistic evaluation focus in the next step. A program in the planning stage will focus its evaluation

differently than a program that has been in existence for several years.

Basic logic model components

INPUTS ACTIVITIES OUTPUTS

SHORT-TERM

EFFECTS/

OUTCOMES

INTERMEDIATE

EFFECTS/

OUTCOMES

LONG-TERM

EFFECTS/

OUTCOMES

Methodology for logic model development

To stimulate the creation of a comprehensive list of these components, use one of the three following methods.

1. Review any information available on the health workforce training program—whether from mission/vision statements,

strategic plans, or key informants—and extract items that meet the denition of activity (something the program and its staff

does) and of outcome (the change you hope will result from the activities).

2. Work backward from outcomes. This is called “reverse” logic modeling and is usually used when a program is given

responsibility for a new or large problem or is just getting started. There may be clarity about the “big change” (most distal

outcome) the program is to produce, but little else. Working backward from the distal outcome by asking “how to” will help

identify the factors, variables, and actors that will be involved in producing change.

3. Work forward from activities. This is called “forward” logic modeling and is helpful when there is clarity about activities but

not about why they are part of the program. Moving from activities to intended outcomes by asking, “So then what happens?”

helps elucidate downstream outcomes of the activities.

HEALTH WORKFORCE TRAINING PROGRAM EVALUATION TOOLKIT: MODULE 2 | PAGE 2

Use the identifying components worksheet listed in the resources section to help you develop a logic model for

your health workforce training program. An example from the University of South Alabama’s health workforce

training program is listed below.

Identifying components example

ACTIVITIES

What will the program and staff do?

OUTCOMES

What are the desired outcomes of the

program?

SEQUENCING

When are these outcomes expected

(short, intermediate, long term)?

1

Improve practice performance in caring

for complex patients

Increased number of complex patients

under care management.

Increased number of patients screened for

substance abuse.

Increased number of patients seen in a

group ofce setting.

Reduction in unnecessary admissions for

health system.

Short-term:

Increased number of complex patients

under care management.

Increased number of patients screened for

substance abuse.

Increased number of patients seen in a

group ofce setting.

Intermediate-term:

Reduced number of unnecessary

admissions for health system.

Long-term:

Care delivered by graduates and learners

measured by well-being and other

markers above 80th percentile.

2

Provide modular education for all

learners on population health, care of

complex patients, and improved patient

engagement.

Increased number of residents who have

knowledge of team-based care of complex

patients.

Increased number physicians who have

extensive team-based population health.

Reduced number of ED visits.

Care delivered by graduates and learners

measured by well-being and other

markers above 80th percentile.

Short-term:

Increased number of residents who have

knowledge of team-based care of complex

patients.

Increased number physicians who have

extensive team-based population health.

Intermediate-term:

Reduced number of ED visits.

Long-term:

Care delivered by graduates and learners

measured by well-being and other

markers above 80th percentile.

3

Provide intense educational opportunity

for medical students regarding value-

based care.

Increased number of students in value-

based care track.

Increased number of students interested

in value-based care.

Residency graduates taking leadership

positions in primary care.

Short-term:

Increased number of students in value-

based care track.

Intermediate-term:

Increased number of students interested

in value-based care.

Long-term:

Increased residency graduates taking

leadership positions in primary care.

Used with permission from the University of South Alabama

Once you have the information outlined in the table, you can develop the sample logic model for your program.

The University of South Alabama’s logic model is shown on page 5 as an example.

HEALTH WORKFORCE TRAINING PROGRAM EVALUATION TOOLKIT: MODULE 2 | PAGE 3

STEP 3: Using and updating your logic model

A logic model provides a critical framework for evaluators and implementers to monitor a program over time.

It is not a static tool. Tracking indicators for each step in the logic model helps determine whether resources

are sufcient and whether activities are being implemented according to plan. This process identies areas

for program renement, mid-course corrections, and/or technical assistance to support ongoing program

implementation.

Examples of the types of information that may provide mid-term feedback to change program implementation:

• Student focus groups on experience in working with complex patients indicate that they want more

experience to feel condent in their skills.

• Patient surveys on care coordination approach identies that patients would like better introduction and

understanding of roles among their care team.

• Clinical process tracking data on number of patients screened for substance use shows improvement at

one of the ve clinical preceptor sites, and no change at the four remaining clinical sites.

HEALTH WORKFORCE TRAINING PROGRAM EVALUATION TOOLKIT: MODULE 2 | PAGE 4

Caring for the Complex Patient in the PCMH — University of South Alabama

SITUATION

Need: To improve poor health of

population through improved care

coordination and engagement

while better training physicians,

mental health providers, and

others to deliver team based care

Desired Result: High performing

care delivery and training

platform, modular educational

program focused on improving

social determinants through

improved patient engagement and

team based care

Enabling “protective” Factors:

Existing population based focus of

residency

Limiting “risk” factors:

Incorporation of medical students

and mental health students

Strategies and best practices:

Use of modular learning activities;

certication approach; pipeline

approach

INPUTS

What we invest (resources)

• Clinical practice staff

• Family medicine faculty

• Mental health faculty

• Pharmacy faculty

• Patient time

• Curriculum time

− Medical student LEAP

experience

− COM III and IV time

− Residency population health

rotation

− Mental health time

− Post graduate physician and

pharmacy time

OUTPUTS

Activities

What we do

• Improved practice performance

regarding complex patients

• Modular education for all

learners on population

health, care of the complex

patient, and improved patient

engagement

• Simulated team based care

delivery training

• Intense educational opportunity

for medical students regarding

value- based care

• Faculty development

Service delivery

Evidence of Program Delivery

• # of complex patients under

care management

• # of patients screened for

substance abuse

• # of patients seen in group

ofce setting

• # of team home visits made

• # of residents and students

with training in population and

care of the complex patient

• # of students in value-based

care track

• # of students engaged in team

based care of complex patients

OUTCOMES-IMPACT

Short term results

(1-4 years)

• Change in # of residents with

knowledge of team based care

of complex pts

• Change in # of students with

experience in team based care

of complex patient

• Change in # of patients

screened for substance abuse

• Change in physicians with

extensive team based

population health experience

Long term results

(5-7 years)

• Reduction in unnecessary

admissions for USA Health

System

• Reduction in ED visits for SA

Health System

• Decrease in admissions within

the last 2 weeks prior to death

in patients cared for by USA

Health System

• Increase in non- rvu to family

physicians in lower Alabama

• Increased student interest in

value based care

Ultimate impact

(8+ years)

• Increased interest amongst

entering students who are

seeking training in value based

training

• USA Residency graduates

successfully seeking

leadership positions in primary

care

• Care delivered by graduates

and learners as measured by

wellbeing and other markers

above 80th percentile.

ASSUMPTIONS

Mental health care delivery in a primary care setting

will be accepted by patients and reimbursed by payers

Learners will nd simulations engaging and will

value improving resource utilization as an equivalent

clinical skill

Regional care organization will value improved clinical

outcomes over volume based metrics in local market

EXTERNAL FACTORS

Payment migrating to value on national level will

continue, sparking student interest

Need for enhanced primary care workforce, mental

health workforce, and team-based focus will be seen

by learners

EVALUATION

1. Learner satisfaction with the educational offerings

2. Learner acquisition of skills necessary to manage complex patients

3. Learner participation in team based activities

4. Graduates undertaking team based care in underserved environment

upon graduation

5. Mental health graduates seek opportunities in primary care setting

upon graduation

6. Reduction in hospitalizations for patients under the care of USAFM and

subsequently USA Health

7. Improvements in patient health attributable to improved primary care

Used with permission from the University of South Alabama

HEALTH WORKFORCE TRAINING PROGRAM EVALUATION TOOLKIT: MODULE 2 | PAGE 5

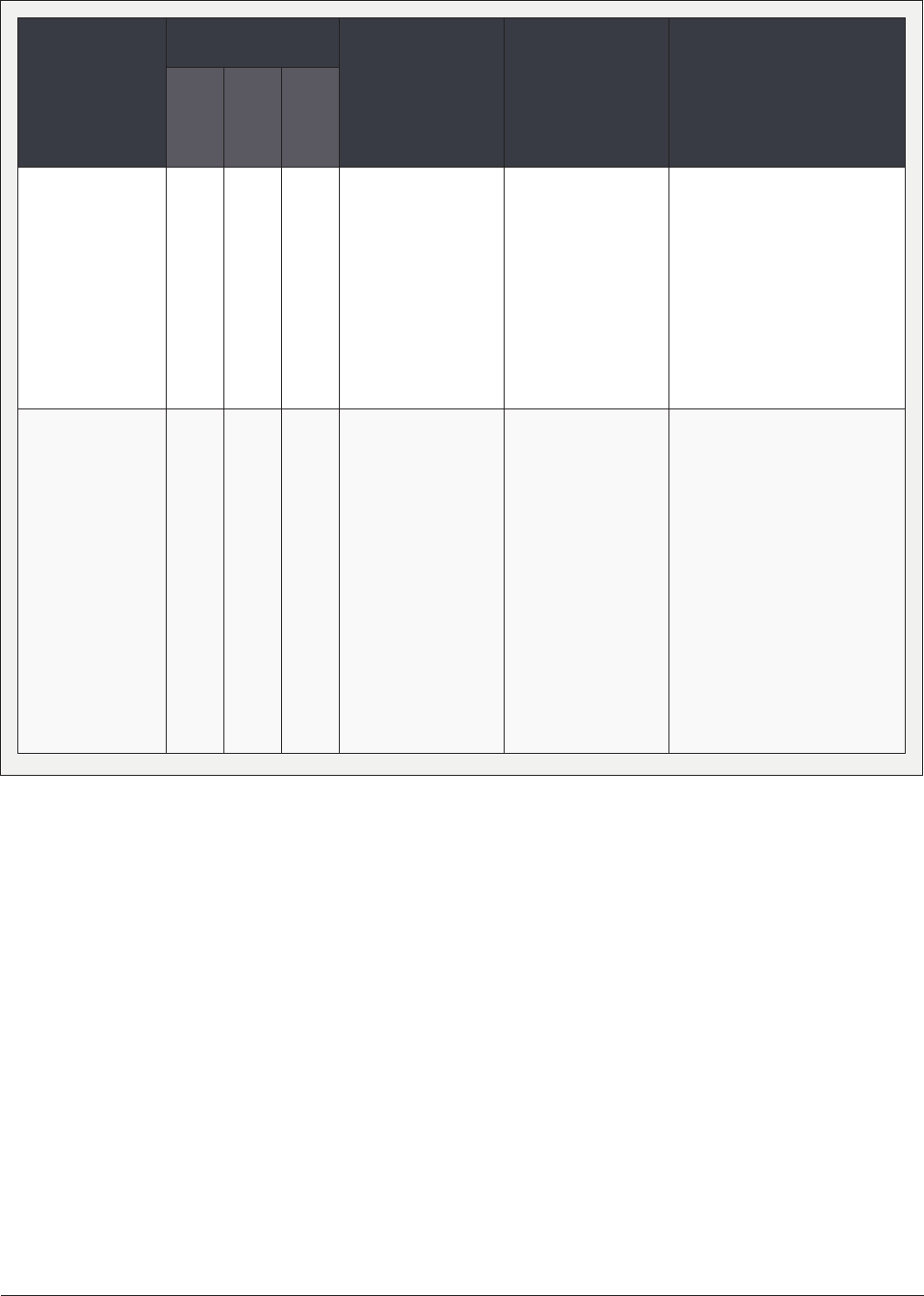

TOOL 2.1

Components of your logic model

ACTIVITIES

What will the program and staff do?

OUTCOMES

What are the desired outcomes of the

program?

SEQUENCING

When are these outcomes expected

(short, intermediate, long term)?

1

2

3

HEALTH WORKFORCE TRAINING PROGRAM EVALUATION TOOLKIT: MODULE 2 | PAGE 6

MODULE 3

Focus Evaluation Design

INTRODUCTION

The purpose of this module is to guide development of the evaluation purpose, questions, and ÿndings. There

may be evaluation questions that you will not have time or resources to answer in a single grant cycle. How do

you prioritize? Now that you have developed your logic model and clearly deÿned your program, the next step is

to focus the scope of your evaluation design.

STEP 1: Determine your health workforce training program stage of development

Identifying the stage of development of the program and/or its components will help you prioritize evaluation

questions and approach. Health workforce training programs vary signiÿcantly in their stage of development and

longevity. If your program is established, the emphasis of the evaluation might be to provide evidence of the

program’s contributions to its long-term goals. If you have a new program, you might prioritize improving or ÿne-

tuning operations.

Program Development Stage Overview

PROGRAM COMPONENT STAGE EVALUATION PURPOSE WHAT TO MEASURE

PLANNING STAGE

(ÿrst year of program)

Determine best structure and design. Process questions on how consistently

program components were implemented,

and which practices facilitated

implementation.

IMPLEMENTATION STAGE

(approximately 2–5 years into program)

*Some programs may be ready to assess

maintenance in year 3, others later.

Program is fully operational (i.e., no

longer a pilot) and available to all

intended trainees.

Implementation process and outcomes.

MAINTENANCE STAGE

(3 or more years into program)

Measuring program results. Short- and long-term outcomes.

Depending on your program’s development stage you may want to include formative evaluation questions as

part of your evaluation plan. For all Primary Care Training Enhancement (PCTE) evaluation plans, HRSA has

asked grantees to measure long-term effects of the program- in particular on graduates’ ability to support a

transformed health care delivery system and the Three Part Aim plus provider well being (more information on

using the Three Part Aim plus provider well being to frame your evaluation is on page 4 of this module).

ADAPTED FROM: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Ofÿce of the Director, Ofÿce of Strategy

and Innovation. Introduction to program evaluation for public health programs: A self-study guide. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,

2011. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/eval/framework/index.htm

Prioritizing evaluation questions by stage of program development

For example, let’s say as part of your health workforce training

you are building a mentorship program and quality improvement

project between community preceptors and trainees. Thinking

through three stages of program development—planning,

implementation, and maintenance—will help you prioritize your

evaluation questions.

In a new program planning stage, formative evaluation questions

may be process-oriented, e.g., “Was the preceptor orientation

sufcient? Is there a better way to structure collaboration

with and support of the preceptors? Should we require three

structured meetings between preceptor mentors and trainees, or

should they be allowed to create custom schedules?”

In the implementation stage, the key questions might be,

“How many quality improvement projects were completed?

How did trainees and preceptors rate the program? What

effects did the quality improvement projects have on clinical

performance in the preceptor sites?”

In the maintenance stage, the program can begin to look at

long-term outcomes of the projects. Include questions such as,

“Did trainees apply what they learned to their clinic work? Did

they take a leadership role in quality improvement in a primary

care setting?”

Approaches to measurement of long-term outcomes

Measuring the long-term effects of your program on graduates can be done with some creativity and

persistence. The graduate outcomes HRSA would like to see for the health workforce training program include

placement in underserved areas, working with vulnerable and underserved populations, and leadership of

graduates in supporting the transformation of the health care delivery system and achievement of the Three

Part Aim. Tools for measurement include surveys of graduates and use of publicly available datasets, and

for graduates who remain within your regional health system, locally available data. The following are some

approaches you can consider for measuring long-term outcomes.

1. Revising your post-graduate survey to include questions on primary care leadership and practicing in

reformed health care settings.

Sample questions:

• Do you lead quality improvement efforts at your organization?

• Is the practice you work in PCMH-certied?

• Do you use a population health management or panel management tool to risk-stratify your patients?

• Do you receive information on cost of care as a participant in an accountable care organization or

managed care plan?

2. Using publicly available data as a proxy for graduate outcomes. Public datasets can provide information

on whether graduates are working in a setting that has embraced elements of a reformed health care

system, and provide information on clinical quality and patient experience at that setting. Some of this

information may be provided at the practice level, and some at the provider level.

• If the practice site of your graduate is known, you can nd out if the practice is PCMH-certied through

NCQA site: http://reportcards.ncqa.org/#/practices/list.

• In some states and regions, primary care practice quality information is publicly available. Examples

include the state of Massachusetts Health Compass (HealthCompassma.org) which publishes both

patient experience and clinical quality data at the practice level. GetBetterMaine.org publishes provider-

level data on clinical quality and patient experience. Because these data sources are not uniformly

available across states or providers, ease of use will depend on the geographic dispersion of your

graduates. Other public information may be available in your region based on state or regional health

reform efforts.

A resource of a sample tracking sheet for long-term outcomes is provided in Module 4: Gather Credible

Evidence. For more guidance on long-term trainee tracking see:

Morgan, P., Humeniuk, K. M., & Everett, C. M. (2015). Facilitating Research in Physician Assistant Programs:

Creating a Student-Level Longitudinal Database. The Journal of Physician Assistant Education: The Ofcial

Journal Of The Physician Assistant Education Association, 26(3), 130–135.

HEALTH WORKFORCE TRAINING PROGRAM EVALUATION TOOLKIT: MODULE 3 | PAGE 2

STEP 2: Assess program intensity

Consider the depth of the program intervention and its potential effect on trainee or patient clinical outcomes.

A short-term shallow intervention is unlikely to affect results, trainee learning, or patient clinical outcomes,

regardless of stage and maturity of implementation. Questions to think about include: How many trainees will it

affect? Over what period of time? What is the level of exposure and intensity?

Consider the previous example of a preceptor program including a mentor and quality improvement project. The

health workforce training program has given trainees the option to choose a quality improvement project with a

four-month timeline. One trainee chooses adult diabetes management, one focuses on adolescent substance

use screening, one on healthy eating counseling for children, another on eating counseling for adults, and the

remaining two on child immunization rates. In this situation there is not a single clinical outcome that can assess

impact across all trainees, nor is four months likely an adequate time to see a clinical impact. However, the

programs that are focused on counseling or screening could assess process measure improvements in those

areas.

STEP 3: Write priority evaluation questions

Consider the stage of development and intensity of the program. What outcomes are reasonable to expect and

measure? Write the three most important evaluation questions.

STEP 4:

Assess constraints

The following questions will help you determine if the priority evaluation questions can be answered during your

grant period.

1. How long do we have to conduct the evaluation?

2. What data sources do we have access to already?

3. Will new data collection be required?

a. If yes, do we have people with skills and time to collect data?

b. Are there any technical, security, privacy, or logistical constraints to the data?

STEP 5: Finalize evaluation questions

Return to your logic model and nalize the evaluation questions for this grant cycle. You may have identied

questions that can be put aside for future evaluation cycles or grant opportunities.

HEALTH WORKFORCE TRAINING PROGRAM EVALUATION TOOLKIT: MODULE 3 | PAGE 3

RESOURCES

Evaluation frameworks

Evaluation frameworks can provide an overall structure and vision for your evaluation. Two frameworks to consider

in developing your evaluation are how to use the Three Part Aim to assess program elements in preparing trainees

for health system transformation, and the RE-AIM framework to understand the program implementation process

and context for replication and sustainability. More detail on these two frameworks is below.

Addressing the Three Part Aim plus Provider Well Being through evaluation

HRSA’s funding announcement for the health workforce training program states the goal of “working to develop

primary care providers who are well prepared to practice in and lead transforming healthcare systems aimed at

improving access, quality of care and cost effectiveness.”

1

THREE PART AIM

Better

Health

Reduced

Health

Disparities

Lower Cost

Through

Improvement

Better

Care

THREE PART AIM PLUS PROVIDER WELL BEING

Reducing

Costs

Provider

Well Being

Patient

Experience

Population

Health

The National Quality Strategy promoted by the Department of Health and Human Services is an overarching plan

to align efforts to improve quality of care at the national, State, and local levels. Guiding this strategy is the Three

Part Aim which is to provide better care, better health/healthy communities and more affordable care.1 Recently,

there has been discussion of expanding to add provider well being, which incorporates improving the work life of

clinicians and staff to the goals. PCTE programs should assess the ways that they are preparing future clinicians to

provide services that improve patient experience, population health, cost effectiveness, and provider well-being.

The table on pages 6 and 7 includes examples of evaluation approaches. The Three Part Aim plus provider well

being’s focus on provider experience and assessing provider resiliency has been added to these resources,

based on health workforce training programs’ feedback and interest. The next module (Module 4: Gather

Credible Evidence) will provide examples of related measures and indicators to consider within your evaluation.

RE-AIM Framework

The RE-AIM framework is a structured approach to identify critical and contextual elements related to translating

evidence-based practices into real-world settings. It can provide a systematic approach for understanding how a

program is “translated” to the health workforce training program, to what extent the experience of your program

could be generalized to other primary care training programs, and how successes and challenges can inform

future projects and initiatives.

More information on RE-AIM can be found at www.re-aim.org.

1 Paterson MA, Falir M, Cashman SB, Evans C, Garr D. Achieving the Triple Aim: A Curriculum Framework for Health Professions Education. Am J Prev

Med.2016:49(2):294-296.

HEALTH WORKFORCE TRAINING PROGRAM EVALUATION TOOLKIT: MODULE 3 | PAGE 4

HEALTH WORKFORCE TRAINING PROGRAM EVALUATION TOOLKIT: MODULE 3 | PAGE 5

Health workforce training RE-AIM Example

The multi-disciplinary program includes primary care residents from pediatrics, internal medicine, and family

medicine. The program includes symposiums inviting community providers and is open to medical students

and other trainees to encourage networking across disciplines and cross learning. Trainees participate in quality

improvement projects of six months at a clinical site to enhance skills and apply knowledge on population health

management and quality improvement.

In this example there are two separate activities within the grant period that could be looked at through the RE-AIM

Framework. Below are example questions that may be used to frame the evaluation.

Example: Health workforce training RE-AIM

R

Reach

SYMPOSIUM

Who participates in the primary care symposium? What types of interactions between

trainees occur?

QUALITY IMPROVEMENT PROJECTS

Which patients are included in trainee quality improvement projects?

SYMPOSIUM

Were the learning objectives for the primary care symposium met?

E

Efcacy/

Effectiveness

QUALITY IMPROVEMENT PROJECTS

What were the clinical operational and/or clinical results of the trainee quality

improvement projects?

Were trainee skills to lead quality improvement projects enhanced?

A

Adoption

SYMPOSIUM AND QUALITY IMPROVEMENT PROJECTS

How representative were the trainee participants of all trainees in primary care?

I

Implementation

SYMPOSIUM

If the symposium model is used again, are there any changes to format or curriculum that

should be considered?

QUALITY IMPROVEMENT PROJECTS

Were there differences in how trainees were supported on their quality improvement projects?

Were there any adaptations to the trainee quality improvement program during the grant period?

If yes, why? What was learned?

M

Maintenance

SYMPOSIUM

What resources or collaboration will be needed to sustain the symposium model in

future years?

QUALITY IMPROVEMENT PROJECTS

What was the reception of the clinical preceptor sites on including trainees as quality

improvement leaders? Is there clinical practice support to continue the program?

Summary of RE-AIM Framework Components

R

Reach

Characteristics of those reached by the program intervention and those who are not reached;

how representative of the general population are they?

E

Efcacy/

Effectiveness

Extent to which an intervention resulted in desirable outcomes (e.g., improved learning of key

concept, mastering of skills, patient improvement).

A

Adoption

Who is/is not participating in the intervention (trainees, faculty, etc.), and how representative

of the program are they?

I

Implementation

How was it done? Fidelity to model, changes, and why. Consistency and costs of implementation.

M

Maintenance Sustainability and institutionalization of model.

Addressing the Three Part Aim plus provider well being through evaluation

THREE PART AIM PLUS

PROVIDER WELL BEING

COMPONENTS

APPROACH DESCRIPTION EXAMPLES SAMPLE MEASURES

Population health-reduced Capitalize on health care Many states and regions State Innovation Model Data on clinical quality,

cost enhancement initiatives in are collecting data from Grants (SIM) cost of care (e.g., total

your state and region. practices as part of their

health care enhancement

initiatives. Consider

how these efforts might

Delivery System Reform

Incentive Payment

Program (DSRIP)

cost of care for Medicaid

enrollees by claims).

provide data for your

Transforming Clinical

evaluation efforts.

Practice Initiatives (TCPCi),

also known as Practice

Transformation Networks

(PTN)

Population health-reduced Use clinical measures Are you working with All FQHCs must report Clinical quality measures

cost reported by precepting clinics that are part of an the UDS clinical quality of immunizations, cancer

sites to funders. ACO or FQHC? measures. These screenings, chronic

You might use their quality

metrics to assess the

clinical quality of your

health workforce training

program participants.

measures are reported at

the clinic level, but your

health center partner may

be able to share provider-

level data.

disease care.

ACO participation may

provide clinics with

monthly data including

utilization from claims and

clinical quality.

Population health Patient-centered

medical home (PCMH)

transformation efforts

provide speciÿc

information on practice-

level quality of care

and an organizational

assessment of the training

environment.

Programs might assess

the number of clinical

training sites that have

achieved recognition

status

-OR-

Assess progress in

attainment of speciÿc

core elements of PCMH

recognition.

The NCQA PCMH

recognition standards or

alternatively, the Safety

Net Medical Home PCMH

assessment.

Note: NCQA PCMH

standards are updated

regularly. Consider which

will be used by your

practice and evaluation

process.

The NCQA PCMH program

is divided into 6 standards

that align with core

components of primary

care:

– PCMH 1: Enhance

access and continuity

– PCMH 2: Identify

and manage patient

populations

– PCMH 3: Plan and

manage care

– PCMH 4: Provide

self-care support and

community resources

– PCMH 5: Track and

coordinate care

– PCMH 6: Measure and

improve performance

Patient experience Use existing patient

experience surveys

whenever possible.

Many practices use

patient experience

surveys; some can

separate results by

provider. This allows

provider-speciÿc results

CAHPS (Consumer

Assessment of Healthcare

Providers and Systems)

PAM (Patient Activation

Measure)

Communication between

provider and patient.

to compare trainee patient

experience ratings to

clinic averages and other

benchmarks.

HEALTH WORKFORCE TRAINING PROGRAM EVALUATION TOOLKIT: MODULE 3 | PAGE 6

Addressing the Three Part Aim plus provider well being through evaluation, continued

THREE PART AIM PLUS

PROVIDER WELL BEING

COMPONENTS

APPROACH DESCRIPTION EXAMPLES SAMPLE MEASURES

Patient experience/access Clinic operational data

can be abstracted from

standard reports or

designed for evaluation

purposes.

Improving patient

access to acute care

appointments.

Use training logs to assess

continuity of care with a

single provider or team.

N/A Wait-time for 3rd next

available appointment.

% of patient appointments

with assigned care team.

Provider resiliency Assessing student

resiliency during the

program can mark their

preparedness for primary

care and heighten

awareness of resiliency

for trainees and program.

Are you providing speciÿc

resiliency training or

are you interested in

understanding trainee

capacity for resiliency?

There is interest in

measuring provider

resilience in primary care

but there are no standards

in validated tools.° The

Professional Quality of Life

Scale (ProQOL) is the most

commonly used measure

of negative and positive

effects of helping those

who experience suffering

and trauma.

Job satisfaction, self-

fulÿllment, anxiety, stress,

and compassion. As a

1-page assessment tool

there is low burden in

use and distribution.

The sensitivity of such

questions requires careful

administrative structuring

to protect respondent

privacy.

2 Robertson HD, Elliott AM, Burton C, Iversen L, Murchi P, Porteous T, and Matheson C. Resilience of primary healthcare professionals: a systematic

review. British Journal of General Practice. June 2016. 66(647).

HEALTH WORKFORCE TRAINING PROGRAM EVALUATION TOOLKIT: MODULE 3 | PAGE 7

MODULE 4

Gather Credible Evidence

Now that you have developed a logic model for your health workforce training program, chosen an evaluation

focus, and selected your evaluation questions, your next task is to gather the evidence. You want credible

data to strengthen the evaluation judgments and the recommendations that follow. You should consider the

following questions:

• What data will be collected? What are the data indicators that you will use for your evaluation?

• Who will collect the data, or are there existing sources you can use? How will you collect and access

the data? What are the data collection methods and sources?

• What are the logistics for your evaluation? When will you collect the data (i.e., what is the timeframe)?

How will the data be entered and stored? How will the security and conÿdentiality of the information be

maintained? Will you collect data on all (trainees), or only a sample?

• How much data (quantity) do you need to collect to answer your evaluation questions?

• What is the quality of your data? Are your data reliable, valid, and informative?

• How often will data be analyzed? What is the data analysis plan?

STEP 1: Select your health workforce training

data indicators

Process indicators focus on the activities to be

completed in a speciÿc time period. They enable

accountability by setting speciÿc activities to be

completed by speciÿc dates. They say what you

are doing and how you will do it. They describe

participants, interactions, and activities.

Outcome indicators express the intended results or

accomplishments of program or intervention activities

within a given time frame. They most often focus

on changes in policy, a system, the environment,

knowledge, attitudes, or behavior. Outcomes can be

short-, intermediate-, or long-term.

Consider the following when selecting indicators for

your health workforce training evaluation.

• There can be more than one indicator for each

activity or outcome.

• The indicator must be focused and measur

e an

important dimension of the activity or outcome.

• The indicator must be clear and speciÿc about

what it will measure.

• The change measured by the indicator should

represent progress toward implementing the

activity or achieving the outcome.

Example health workforce training

program indicators

PROGRAM COMPONENT INDICATOR

Simulated team-based care

delivery training

PROCESS: Number of

trainings

OUTCOME: Increased trainee

knowledge based on semi-

annual survey assessment

Faculty development on

interdisciplinary learning

PROCESS: Number of staff

trained

OUTCOME: Number

of presentations and

publications by faculty

with research including

interdisciplinary teams.

ADAPTED FROM: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Ofÿce of the Director, Ofÿce of Strategy

and Innovation. Introduction to program evaluation for public health programs: A self-study guide. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,

2011. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/eval/framework/index.htm

STEP 2: Select your data collection methods and sources

Now that you have determined the activities and

outcomes you want to measure and the indicators you

will use to measure progress on them, you need to

select data collection methods and sources.

Consider whether you can use existing data

sources (secondary data collection) to measure your

indicators, or if you will need to collect new data

(primary data collection).

Secondary Data Collection

Existing data collection is less time consuming and

human resource intensive than primary data collection.

Using data from existing systems has the advantages

of availability of routinely collected data that has

been vetted and checked for accuracy. However, you

will have less exibility in the type of data collected,

and accessing data from existing systems may be

costly. Examples of existing data sources that may be

relevant for health workforce training evaluation:

1.

Student tracking systems such as eValue that

show demographics of patients that trainees have

seen, and the health conditions of those patients.

2. Traditional and non-traditional sources for

surveying graduates. Traditional surveys

distributed through the alumni ofce, or (non-

traditional) LinkedIn or Facebook groups.

3. Existing clinical data sources reported by

organization. For safety-net clinics, this could

be clinical performance measures reported

through the Uniform Data System (UDS) to

HRSA. These measures include chronic disease

management and preventive health indicators

for cancer screening, immunizations, behavioral,

and oral health, and are reported on an annual

basis for all patients within the health center

organization. Consider other secondary sources

available based on health care enhancement

and payment based on value. Examples include

measures being reported as part of participation

in an accountable care organization, or for

some organizations participating in CMS-

funded practice transformation efforts, such as

Comprehensive Primary Care Initiative (CPCi).

Clinics that are part of a Medicaid Managed

Care organization may receive summary claims

data or clinical feedback on patient use of the

hospital and emergency room.

4. Patient satisfaction surveys from the Consumer

Assessment of Healthcare Providers and

Systems (CAHPS), or other sources such as the

Midwest Clinicians’ Networks’ surveys specic

to behavioral health and employee satisfaction.

Primary Data Collection

The benet of primary data collection is that you can

tailor it to your health workforce training evaluation

questions. However, it is generally more time

consuming to collect primary data. Primary data

collection methods include:

• Surveys: personal interviews, telephone

interviews, instruments completed by respondent

received through regular or e-mail.

• Group discussions/focus groups.

• Observation.

• Document review, such as medical records,

patient diaries, logs, minutes of meetings, etc.

Quantitative versus Qualitative Data

You will also want to consider whether you will collect

quantitative or qualitative data or a mix of both.

Quantitative data are numerical data or information

that can be converted into numbers. You can use

quantitative data to measure your SMART objectives

(for more on developing SMART objectives, see

Module 3). Examples:

• Number of trainees.

• Percent of trainees who have graduated.

• Average number of trainees who pass boards on

rst attempt.

• Ratio of trainees to faculty.

Qualitative data are non-numerical data that can help

contextualize your quantitative data by giving you

information to help you understand why, how, and

what is happening with your health workforce training

program. For example, you may want to get the opinions

of faculty, trainees, and clinic staff on why something is

working well or not well. Examples include:

• Meeting minutes to document program

implementation.

• Interviews with trainees, providers, faculty,

or patients.

• Open-ended questions on surveys.

• Trainee writing, essays, or journal entries.

• Focus groups with former or current students.

HEALTH WORKFORCE TRAINING PROGRAM EVALUATION TOOLKIT: MODULE 4 | PAGE 2

Mixed Methods

Sometimes a single method is not sufÿcient to measure an activity or outcome because what is being measured

is complex and/or the data method/source does not yield reliable or accurate data. A mixed-methods approach

will increase the accuracy of your measurement and the certainty of your health workforce training evaluation

conclusions when the various methods yield similar results. Mixed-methods data collection refers to gathering

both quantitative and qualitative data. Mixed methods can be used sequentially or concurrently. An example

of sequential use would be conducting focus groups (qualitative) to inform development of a survey instrument

(quantitative), and conducting personal interviews (qualitative) to investigate issues that arose during coding

or interpretation of survey data. An example of concurrent use of mixed methods would be conducting focus

groups or open-ended personal interviews to help afÿrm the response validity of a quantitative survey. For more

information on using mixed-methods approaches to evaluation, see “Recommendations for a Mixed-Methods

Approach to Evaluating the Patient-Centered Medical Home.”

1

Matrix of potential evaluation areas and publicly available tools/measures

TOPIC TOOL NAME BRIEF DESCRIPTION CONSIDERATIONS FOR USE

Team-based care Team Development Measure Measures a clinical team’s Appropriate for variety of

Developed and distributed

by PeaceHealth, a nonproÿt

health care system with

medical centers, critical

access hospitals, clinics, and

laboratories in Alaska, Oregon,

and Washington.

development level. Can

be used as a performance

measure to promote quality

improvement in team-based

health care. Levels determined

by measuring ÿrmness of

components on a team.

student types.

Publicly available. Authors

request permission for use.

Population health Patient Centered Medical

Home Assessment-A

Developed by the MacColl

Center for Health Care

Innovation at the Group Health

Research Institute and Qualis

Health for the Safety Net

Medical Home Initiative.

Helps sites understand current

level of “medical homeness”

and identiÿes opportunities

for improvement. Helps sites

track progress in practice

transformation if completed at

regular intervals.

Assess practice-level progress

on providing a population

health approach to primary

care delivery.

Integration of primary care

and behavioral health

Site Self-Assessment

Developed by the Maine

Health Access Foundation.

Measures integration of

behavioral health and primary

care at site level.

Could be used at practice-site

level.

Community health Methods and Strategies

for Community Partner

Assessment

Developed for the Health

Professions Schools in Service

to the Nation program.

Assesses program

engagement with community

partners who provide service

learning opportunities for

trainees.

May be useful for PCTE

programs that engage

community health partners for

student learning in community

health programs (e.g.,

housing, food security, and

legal advocacy).

1 Goldman R.E., Parker D., Brown J., Eaton C., Walker J., & Borkan J. Recommendations for a Mixed°Methods Approach to Evaluating the Patient°Centered

Medical Home. Annals of Family Medicine, 2015;13(2):168°75.

HEALTH WORKFORCE TRAINING PROGRAM EVALUATION TOOLKIT: MODULE 4 | PAGE 3

Example Data Indicators and Data Sources Worksheet

Use the following worksheet to identify the indicators and the data methods/sources for each component of your evaluation.

LOGIC MODEL COMPONENTS

IN EVALUATION FOCUS

INDICATOR(S) OR

EVALUATION QUESTIONS

DATA METHOD(S)/SOURCE(S)

1

Enhanced trainee knowledge and

conÿdence in addressing social

determinants of health.

Are trainees able to address social

determinants of health?

Is the patient experience improved as a

result of provider training?

Trainee journal re°ections on ability to

meet patient needs, before and after

program implementation.

Patient satisfaction surveys with questions

on ability of care team to help them

overcome housing/food/other barriers.

2

Interdisciplinary training enhances

communication between trainees and

learning to work as a team caring for

patients with chronic conditions.

Do trainees opt to work in settings with

interdisciplinary teams?

Are the clinical outcomes improved for

patients with chronic disease?

Graduate survey incorporates questions

on team-based care.

Comparison of chronic disease indicators

in interdisciplinary team patient panels

with those at clinical sites without

interdisciplinary teams.

RESOURCES

Patient Experience Surveys

• CAHPS: Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems. Available through the Agency for

Healthcare Research and Quality

• Midwest Clinicians Network: Surveys of patient experience in medical, behavioral, and oral health and staff

satisfaction.

Secondary Clinical Data Sources

• Uniform Data System (UDS): Clinical quality measures collected and reported by health centers.

• CMS Primary Care Transformation initiatives may be a source of data if your clinical sites are participating.

Consider information from the Primary Care Transformation Initiative and Multi-payer Advanced Primary

Care Practice Demonstration and the Transforming Clinical Practice Initiative, which is supporting more than

14,000 clinical practices through September 2019.

HEALTH WORKFORCE TRAINING PROGRAM EVALUATION TOOLKIT: MODULE 4 | PAGE 4

TOOL 4.1

Data Indicators and Data Sources Worksheet

Use the following worksheet to identify the indicators and the data methods/sources for each component of your

evaluation.

LOGIC MODEL COMPONENTS

IN EVALUATION FOCUS

INDICATOR(S) OR

EVALUATION QUESTIONS

DATA METHOD(S)/SOURCE(S)

1

2

3

HEALTH WORKFORCE TRAINING PROGRAM EVALUATION TOOLKIT: MODULE 4 | PAGE 5

TOOL 4.2

Data Collection Worksheet

Use the following worksheet to identify the data collection methods and sources, how data will be collected,

and by whom.

DATA COLLECTION

METHOD/SOURCE

FROM WHOM WILL THESE

DATA BE COLLECTED

BY WHOM WILL THESE DATA

BE COLLECTED AND WHEN

SECURITY OR

CONFIDENTIALITY STEPS

1

2

3

HEALTH WORKFORCE TRAINING PROGRAM EVALUATION TOOLKIT: MODULE 4 | PAGE 6

HEALTH WORKFORCE TRAINING PROGRAM EVALUATION TOOLKIT: MODULE 4 | PAGE 7

TOOL 4.3

Long-Term Trainee Tracking Worksheet

Sample trainee tracking template

Graduate name

Year

Program

Location

of practice

Gender

Practice Type (hospital

afliate, FQHC, free

clinic, private practice)

Percent of patients

who are on Medicaid/

uninsured

Leadership roles

Clinical quality

information

Years of practice at

current site

MODULE 5

Justify Conclusions/Data Interpretation and Use

Why is this important?

Data interpretation is typically the role of the

“researcher/evaluator” but involving stakeholders can

lead to a deeper understanding of the ndings, and

more effective use of the data. If stakeholders agree

that the conclusions are justied, they will be more

inclined to use the evaluation results for program

improvement. This module considers a process to

interpret health workforce training data in collaboration

with stakeholders.

STEP 1: Analyze and synthesize ndings

Data analysis will be guided by the evaluation plan

developed from your logic model and evaluation

framework (detailed in Modules 2 and 3).

The analysis phase includes the following tasks:

• Organize and classify the quantitative and

qualitative data collected. This includes the steps

of cleaning data and checking for errors.

• Tabulate the data into counts and percentages for

each indicator.

• Summarize data and include stratication if

appropriate. At the trainee level you may stratify

by trainee type, cohort, or practice site. For

clinical data you may stratify by provider team,

practice site, or patient demographics.

• Compare results with appropriate information.

Depending on your evaluation design you may

make comparisons over time using the same

indicator, or may compare locations, practices, or

cohorts of trainees. You may also compare results

to established targets or benchmarks.

• If using mixed-methods analysis, take important

ndings from one source and compare to other

sources.

• Present the results in an easily understandable

manner, and tailor it to your audience.

Mixed-Methods Example

If you were asking these questions: Do trainees feel prepared

to provide care to complex patients in a team-based

environment? Do patients feel care is coordinated across team

members?

A mixed-methods approach could pair the results from patient

focus groups with results from trainee surveys on providing

care in an interdisciplinary team-based environment. These

results might also be paired with clinical outcomes for

the patients such as patient blood pressure or depression

screening scores.

Mixed-Method Analysis Example within

health workforce training program:

Transformed Primary Care through

Addressing Social Determinants of Health

A health workforce training program has decided to focus

on preparing students to address social determinants of

health. The metric of interest for this program is assessing

improvement of housing status, as the safety-net clinic has

a large uninsured and transient population. As part of the

program, evaluators are collecting data through a patient

satisfaction survey, through focus groups with trainees at

the beginning and end of the program, and through chart

abstraction of the EHR. For the mixed-method analysis, they

planned a pre-post quantitative analysis of the number of

clinical training site patients who have “unstable housing”

status. The focus groups with trainees provided information

on resident experience in assessing and supporting patients

without housing by connecting them to social work staff

as part the interdisciplinary team. This was combined with

data from surveys on patient experience accessing care and

services. The combination of data sources will inform the

quantitative data on “improved housing status.” If success

is not as high as expected, the data from the student focus

groups may indicate barriers, and the data from patients may

provide information on ways the patients received assistance

in improving access to housing. If housing status was not

improved, patient feedback might indicate if other support

was provided.

ADAPTED FROM: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Ofce of the Director, Ofce of Strategy

and Innovation. Introduction to program evaluation for public health programs: A self-study guide. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,

2011. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/eval/framework/index.htm

STEP 2: Setting program standards

Articulate the values that will be used to consider a program “successful,” “adequate,” or “unsuccessful.”

Program standards are the metrics by which the evaluation results will be assessed after completion of program

data analysis. Using the example of a program that is addressing social determinants of health, consider whether

the result of a 5 percent or a 50 percent increase in patients who have stable housing is a meaningful result. The

purpose of including stakeholders in setting benchmarks is to understand what the users of evaluation ndings

consider meaningful. A faculty member, student, and patient may have different interpretations of whether

increasing the percent of patients who have stable housing is successful at a 5 versus 50 percent level. Including

stakeholders in developing the benchmark at the outset of the evaluation will set the team up for consensus on

interpretation of ndings at the end of the analysis.

• Think about what informs the choice of

benchmarks. In addition to the value and

interpretation of results by stakeholders,

consider the external context that may inform the

development of the benchmark.

• What is the average performance at similar

practices/organizations?

• Are there standards that the clinic is being held

to by external funders?

•

Are there preset institutional goals for the metric?

• What is realistic to achieve in the timeframe of

the evaluation?

What is the approach if there is no benchmark?

Not all evaluation metrics will have an external

benchmark or even a baseline for which to compare

results. In cases where there is no external benchmark,

consider whether data collected from multiple clinical

sites within the organization can be a reference point.

For example, if using a provider or trainee satisfaction

survey that was tailored to the organization,

comparison with other organizations may not be

available but comparison across departments or sub-groups may provide insights to the data. When benchmark

data is not available, conversation with stakeholders becomes a more important way to build consensus on what

is meaningful change during the project period, and what can be achieved with time and resources available.

Example benchmarks per objective

OBJECTIVE 1: Develop skills to implement, evaluate, and

teach practice transformation and population health

among trainees.

Prog

ram standards:

• 100 percent of trainees will complete a practice

transformation or population health project.

• Trainees will rate their satisfaction with the program

components an average of 7 on a 10 point Likert scale.

• Trainees will have improved one clinical measure during

the population health project.

OBJECTIVE 2: Evaluate quality and cost of care within the

clinical training environments used by the trainees.

Program standards:

• Improve practice-level measures for two clinical quality

measures over a 2-year period.

• Review use and cost data for 20 percent of patients in

clinical training environments and include as part of

trainee data review for population health.

HEALTH WORKFORCE TRAINING PROGRAM EVALUATION TOOLKIT: MODULE 5 | PAGE 2

STEP 3: Interpretation of ndings and making judgements/recommendations

Judgments are statements about a program’s merit, worth, or signicance that are formed when you compare

ndings against one or more selected program standards. As you interpret data and make recommendations, be

sure to:

• Consider issues of context.

• Assess results against available literature and results of similar programs.

• If multiple methods have been employed, compare different methods for consistency in ndings.

• Consider alternative explanations.

• Use existing standards as a starting point for comparisons.

• Compare actual with intended outcomes.

• Document potential biases.

• Examine the limitations of the evaluation.

The interpretation process is also aided by review of ndings with stakeholders. Presenting the summarized

data to stakeholders helps validate the conclusions and may offer new insights to the results. Most importantly it

creates buy-in of the ndings and any action steps to follow.

Engaging patients in interpretation

Patient perspectives and satisfaction are one component of assessing ability to meet the Three Part Aim. Not

all health workforce training programs will include patient experience data, but those that do may be curious

about how to involve patients in data interpretation. Sharing results with patients may be part of your project

plan to include diverse stakeholder perspectives. Information might be shared through live presentation at a

patient advisory group or patient advisory council meeting. Alternatively, summary results could be included in

an infographic and posted at clinics or included in a patient newsletter. Although the latter option would limit

direct feedback, it conveys that the organization values communication with patients, as well as its research

and quality improvement efforts. For more information on patient advisory groups see the Patient and Family

Advisory Council Getting Started Toolkit.

Interpretation Guide

Example: Transformed Primary Care through Addressing Social Determinants of Health

Outcome of interest: Assessing trainees’ role in addressing social determinants of health through improved housing status of patients.

POINTS TO CONSIDER IN

INTERPRETATION OF DATA

SPECIFIC EXAMPLE FROM A HEALTH WORKFORCE TRAINING PROGRAM

Consider limitations to the data.

Check data for errors.

The housing status data are pulled from an EHR. Consider limitations such as:

• Are patients included if the status is left blank?

• Are only those patients who saw a physician included? For example, if patients came

in for lab tests or immunizations only, were they excluded?

Was the analysis limited to subgroups (e.g., cases with complete data, patients receiving

medical services)?

Ensure that your ndings and interpretation are limited to the data available and are not

overstated.

Consider issues of context when

interpreting data.

Were there changes in housing availability at local shelters or other policy changes that

would affect the ability of increasing stable housing during the time period of study?

Were there changes in the relationship with the local housing director, and collaborative

meetings with community partners that would affect how trainees interacted with clinic to

support housing for patients during the program period?

Assess results against available

literature and results of similar

programs.