February 2008

ProcessCover.ai 3/5/2008 10:11:38 AM

Suggested Citation

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Introduction to Process Evaluation in Tobacco Use Prevention and

Control. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,

National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Oce on Smoking and Health; 2008.

Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/publications/index.htm.

Introduction to Process

Evaluation in Tobacco Use

Prevention and Control

February 2008

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The manual was prepared by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Oce on Smoking and Health.

Matthew McKenna, Director

Corinne Husten, Branch Chief, Epidemiology Branch

Robert Merritt, Team Lead, Evaluation Team

Donald Compton, Project Lead

Nicole Kuiper

Sheila Porter

Contributing Authors

Paul Mattessich, Wilder Research Center

Patricia Rieker, Boston University

Battelle Centers for Public Health Research and Evaluation

Pamela Clark

Mary Kay Dugan, Task Leader

Carol Schmitt

RTI International

Barri Burrus

Suzanne Dolina

Erika Fulmer, Task Leader

Maria Girlando

Michelle Myers

We thank the members of the Editorial Review Group and the Expert Panel for contributing their expertise and

experience in developing and reviewing this manual.

Editorial Review Group

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Deborah Borbely

Robert Merritt

Michael Schooley

Gabrielle Starr

Debra Torres

Tobacco Technical Assistance Consortium

Pamela Redmon

State Health Department Representatives

Jennifer Ellsworth, Minnesota

Lois Keithly, Massachusetts

Mike Placona, North Carolina

Scott Proescholdbell, North Carolina

Saint Louis University

Douglas Luke

Nancy Mueller

i

Expert Panel

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Deborah Borbely

Robert Robinson

Michael Schooley

Brick Lancaster

Patty McLean

Lisa Petersen

Gabrielle Star

Deborah Torres

Michael Baizerman, University of Minnesota

Ursula Bauer, New York Department of Health

Robert Goodman, University of Pittsburgh

Donna Grande, American Medical Association

Paul Mattessich, Wilder Research Center

Edmund Ricci, University of Pittsburgh

Todd Rogers, Public Health Institute

Stacy Scheel, More Voices, Inc.

Laura Linnan, University of North Carolina

Douglas Luke, Saint Louis University

Karla Sneegas, Indiana Tobacco Prevention and Cessation Agency

Frances Stillman, Johns Hopkins University

CDC acknowledges the following National Tobacco Control Program (NTCP) program managers and their sta for

participating in interviews to identify key factors associated with successful tobacco use prevention and control

programs. We also thank the Ohio Tobacco Use Prevention and Control Foundation for their participation.

Joann Wellman Benson, California

Karen DeLeeuw, Colorado

Joan Stine, Maryland

Lois Keithly, Massachusetts

Paul Martinez, Minnesota

Sally Malek, North Carolina

Terry Reid, Washington

Joan Stine, Ohio

Ken Slenkovitch, Ohio Tobacco Use Prevention and Control Foundation

ii

Contents

Contents

Section Page

Acknowledgements i

1. Introduction 1

1.1 The Planning/Program Evaluation/Program Improvement Cycle...................................................................... 2

1.2 Distinguishing Process Evaluation from Outcome Evaluation ............................................................................ 3

2. Purposes and Benets of Process Evaluation 4

2.1 Denition of Process Evaluation..................................................................................................................................... 4

2.2 Scope of Tobacco Control Activities Included in a Process Evaluation............................................................. 4

2.3 Purposes: How Does Process Evaluation Serve You?............................................................................................... 4

2.3.1 Program Monitoring .......................................................................................................................................... 5

2.3.2 Program Improvement ..................................................................................................................................... 5

2.3.3 Building Eective Program Models..............................................................................................................7

2.3.4 Accountability...................................................................................................................................................... 7

2.4 Users and Uses of Process Evaluation Information ................................................................................................11

2.4.1 Users ......................................................................................................................................................................11

2.4.2 Uses........................................................................................................................................................................14

3. Information Elements Central to Process Evaluation 17

3.1 Indicators of Inputs/Activities/Outputs .....................................................................................................................17

3.2 Comparing Process Information to Performance Criteria ...................................................................................21

4. Managing Process Evaluation 29

4.1 Managing Process Evaluation: A 10-Step Process ..................................................................................................29

4.1.1 Purpose: Why Use the 10-Step Process for Managing Evaluation?.................................................29

4.1.2 Roles of the Advisory Group, Evaluation Facilitator, and Evaluator................................................30

4.1.3 Stages and Steps of the 10-Step Process .................................................................................................31

4.1.4 Lessons Learned From Implementing the 10-Step Process ..............................................................35

4.2 The Program Evaluation Standards and Protecting Participants in Evaluation Research........................37

4.2.1 The Program Evaluation Standards...................................................................................................................37

iii

Contents

4.2.2 Protecting Participants in Evaluation Research ............................................................................................38

4.3 Choosing a Process Evaluation Design (Methodology) .......................................................................................39

4.4 Process Evaluation—Beyond a Single Study............................................................................................................41

5. Conclusion 43

Glossary of Terms 45

Appendices

A CDC’s Framework for Program Evaluation ................................................................................................................47

B Detailed List ofThe Joint Committee on Standards for Evaluation: The Program Evaluation Standards...49

C Additional Information on the Purpose, Selection, and Roles of the Evaluation Advisory Group .......53

D Process Evaluation Questions and Logic Model from the Center for Tobacco Policy Research ............57

References 59

iv

Exhibits

EXHIBITS

Number Page

1-1 CDC’s Framework for Program Evaluation ........................................................................................................................... 2

1-2 Logic Models................................................................................................................................................................................... 3

2-1 Four Primary Purposes of Process Evaluation ..................................................................................................................... 8

3-1 Information Commonly Obtained in a Process Evaluation ..........................................................................................18

3-2 Inputs—Comparing Indicators to Criteria..........................................................................................................................22

3-3 Activities and Outputs—Comparing Indicators to Criteria..........................................................................................24

3-4 Tobacco-Related Disparities: Activities and Outputs—Comparing Indicators to Criteria................................25

4-1 Overview of the 10-Step Process for Managing Evaluation.........................................................................................32

4-2 Steps and Sta Responsibilities in the 10-Step Process ................................................................................................33

D-1 Strategy 1 Logic Model: Show Me Health—Clearing the Air About Tobacco .......................................................58

Case Examples Based on Logic Model Categories

Assessment of Learning from truth

sm

: Youth Participation in Field Marketing Techniques to Counter Tobacco

Advertising ...................................................................................................................................................................................... 9

Outcome and Process Evaluation of a School-Based, Informal, Adolescent Peer-Led Intervention to Reduce

Smoking..........................................................................................................................................................................................10

Stakeholder Advisory Board: The North Carolina Youth Empowerment Study.....................................................................13

Assessing the Eectiveness of a Training Curriculum for Promotores, Spanish-Speaking Community Health

Outreach Workers........................................................................................................................................................................14

Assessment of Use of Best Practices Guidelines by 10 State Tobacco Control Programs ..................................................15

Incorporating Process Evaluation Findings into Development of a Web-Based Smoking Cessation Program for

College-Aged Smokers..............................................................................................................................................................16

Case Examples Based on Process Information Components

Implementation of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation’s Community Health Promotion Grant Program............26

New York Statewide School Tobacco Policy Review........................................................................................................................27

Elimination of Secondhand Smoke through the Seattle and King County Smoke-Free Housing Initiative ...............28

v

Introduction

1. INTRODUCTION

Tobacco use in the United States is the single most preventable cause of death and disease.

1

The Centers for

Disease Control and Prevention’s Oce on Smoking and Health (CDC/OSH) created the National Tobacco Control

Program (NTCP) to foster and support coordinated, nationwide, state-based activities to advance its mission to

reduce disease, disability, and death related to tobacco use.

CDC/OSH has identied four program goal areas:

• Preventing initiation of tobacco use among young people;

• Eliminating nonsmokers’ exposure to secondhand smoke;

• Promoting quitting among adults and young people; and

• Identifying and eliminating tobacco-related disparities.

To determine the eectiveness of NTCP programs, both their implementation and their outcomes must be

measured.

2

This manual is intended to provide process evaluation technical assistance to OSH sta, grantees and partners. It

denes process evaluation and describes the rationale, benets, key data collection components, and program

evaluation management procedures. It also discusses how process evaluation links with outcome evaluation and

ts within an overall approach to evaluating comprehensive tobacco control programs. Previous CDC initiatives

have provided resources for designing outcome evaluations. (See, for example, the CDC framework depicted in

Exhibit 1-1.) This manual complements CDC’s approach to outcome evaluation by focusing on process evaluation

as a way to document and measure implementation of NTCP programs.

The content of this manual reects the priorities of CDC/OSH for program monitoring and evaluation, and

augments two other CDC/OSH publications: Key Outcome Indicators for Evaluating Comprehensive Tobacco Control

Programs

3

and Introduction to Program Evaluation for Comprehensive Tobacco Control Programs.

2

This manual:

• Provides a framework for understanding the links between inputs, activities, and outputs and for assessing

how these relate to outcomes; and

• Can assist state and federal program managers and evaluation sta with the design and implementation

of process evaluations that will provide valid, reliable evidence of progress achieved through their tobacco

control eorts.

As you read this manual, keep in mind that it is not a “cookbook” for process evaluation. State and local programs

have unique features and contexts that create a need for dierent types of process-related information. This

manual does explain general principles of process evaluation and provides a guide for determining what

types of information to gather. Also, be mindful that process evaluation of an overall comprehensive state

program such as tobacco control is not typically conducted because the scope of such an evaluation would

1

Introduction to Process Evaluation in Tobacco Use Prevention and Control

not be practical and would be extremely costly. Rather, process evaluation is typically used to evaluate a given

component or activity within an overall comprehensive program. Finally, please note that for the purposes of

this manual, the terms program, project, and intervention are used interchangeably.

1.1 The Planning/Program Evaluation/Program Improvement Cycle

Evaluation is a systematic process to understand what a program does and how well the program does it.

Evaluation results can be used to maintain or improve program quality and to ensure that future planning can

be more evidence-based. Evaluation constitutes part of an ongoing cycle of program planning, implementation,

and improvement.

Exhibit 1-1 provides a visual representation of the six-step CDC framework for general program evaluation.

4

The six steps in the CDC framework represent an ongoing cycle, rather than a linear sequence, and addressing

each of the steps is an iterative process.

4

Implicit in the framework is the connection between evaluation and

planning. Additional information about each step is provided in Appendix A.

Exhibit 1-1: CDC’s Framework for Program Evaluation

Standards

Utility

Feasibility

Propriety

Accuracy

Steps

1. Engage

Stakeholders

2. Describe

the Program

3. Focus the

Evaluation Plan

4. Gather Credible

Evidence and

Support

5. Justify

Conclusions and

Recommendations

6. Ensure Use

and Share

Lessons Learned

SOURCE: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Framework for program evaluation in public health. MMWR

1999;48(RR11):1–40.

2

Section 1—Introduction

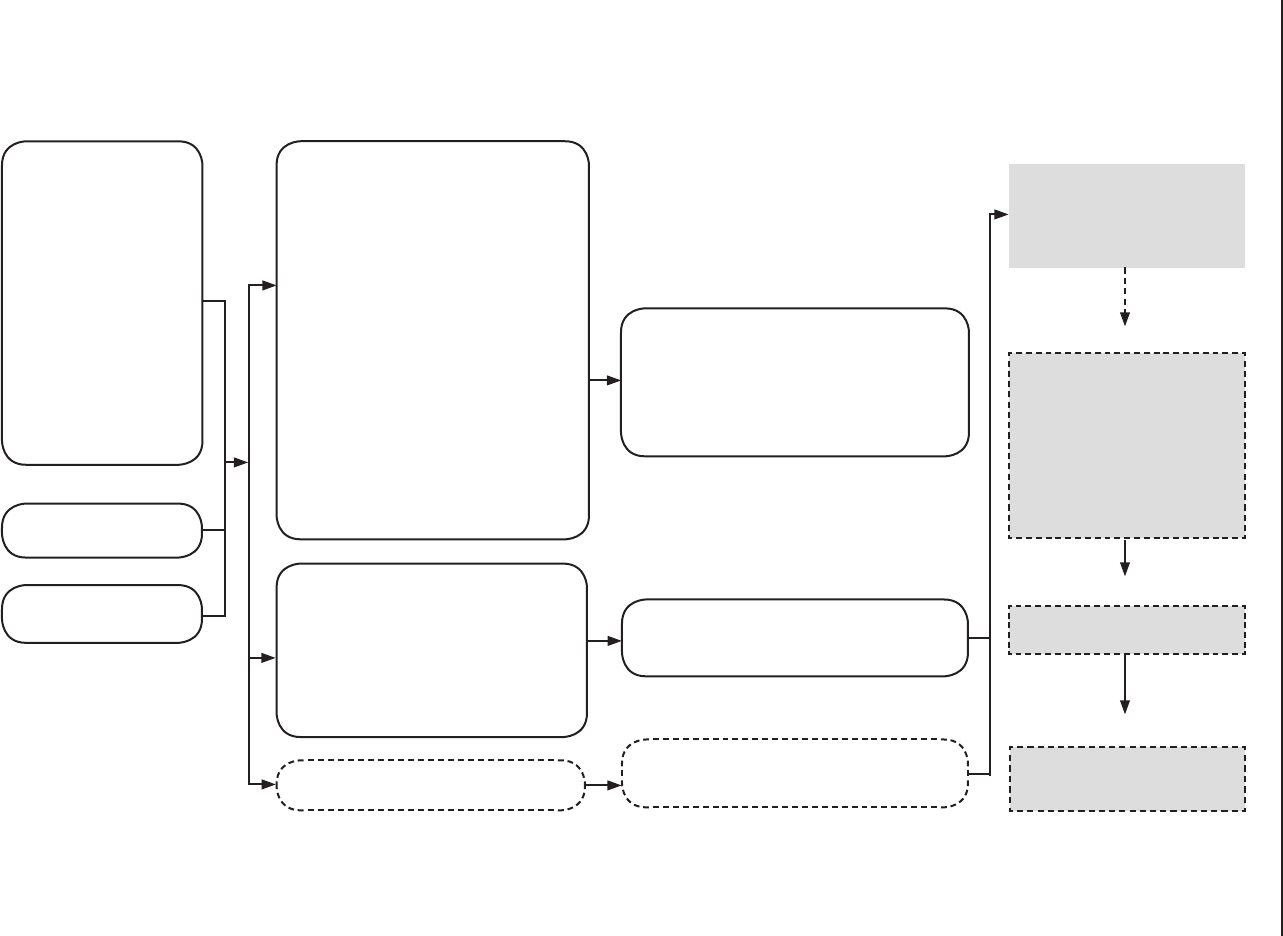

1.2 Distinguishing Process Evaluation from Outcome Evaluation

The NTCP is guided by logic models which address each of the four goals described earlier. The CDC/OSH

approach to tobacco control evaluation is also based in the use of logic models. As shown in Exhibit 1-2, logic

models specify program inputs, activities, outputs, and outcomes (short-term, intermediate, and long-term).

2,3

(See Glossary for denition of terms.)

Exhibit 1-2: Logic Models

Inputs Activities

Intermediate

Outcomes

Long-term

Outcomes

Outputs

Short-term

Outcome

To date, CDC/OSH has developed an approach that emphasizes the last three boxes in Exhibit 1-2, focusing

on outcomes and providing resources to enable program sta to measure and report them. This is outcome

evaluation.

The NTCP has focused on outcome evaluations for several good reasons. Outcome evaluation allows researchers

to document health and behavioral outcomes and identify linkages between an intervention and quantiable

eects. Also, epidemiologists and other practitioners often have a well-developed evidence base for population-

level intervention outcomes, making it feasible to conduct outcome evaluations.

On the other hand, process evaluation focuses on the rst three boxes of the logic model. It enables you to

describe and assess your program’s activities and to link your progress to outcomes. This is important because

the link between outputs and short-term outcomes remains an empirical question. Unlike outcome evaluations,

process evaluations often use practice wisdom (that is, the observations and opinions of professionals in the

eld) to help identify the links between inputs/activities/outputs and short-term outcomes.

A variety of evidence-based guidance is available for NTCP grantees. For example, anticipating the new funds

available to states from the 1998 Master Settlement Agreement (MSA), in 1999, CDC/OSH published Best

Practices for Comprehensive Tobacco Control Programs (Best Practices).

1

This was the rst document to describe the

nine core components of a comprehensive tobacco control program. Best Practices also contained a formalized

set of funding recommendations which helped shape state tobacco control programs by providing national

frameworks and standards.

5

Since Best Practices was released, new guides and reviews have been published. For

instance, the Guide to Community Preventive Services,

6

and the California Communities of Excellence in Tobacco

Control

7

establish planning frameworks that help to dene state activities, expected outputs, and standards

useful for process evaluation. We have included an example of an actual logic model for a process evaluation

(Appendix D), which was provided by the Center for Tobacco Policy Research (CTPR), Saint Louis University

School of Public Health.

3

Introduction to Process Evaluation in Tobacco Use Prevention and Control

2. PURPOSES AND BENEFITS OF PROCESS EVALUATION

This chapter is intended to answer fundamental questions about the value and implementation of process

evaluation within tobacco use prevention and control eorts.

2.1 Denition of Process Evaluation

Process evaluation, as one aspect of overall program evaluation, is:

The systematic collection of information on a program’s inputs, activities, and outputs, as well as the

program’s context and other key characteristics.

Process evaluation involves the collection of information to describe what a program includes and how it

functions over time. In and of itself, the information is “neutral.” It is merely descriptive, although people often

attach meaning and value to the information. It does not reect “quality” until you compare it to an external set

of standards or criteria.

Process evaluations can occur just once, periodically throughout the duration of a program, or continuously. The

type of information gathered, and its frequency, will depend on the kinds of questions that you seek to answer.

2.2 Scope of Tobacco Control Activities Included in a Process Evaluation

In evaluations of tobacco-control programs, a question commonly arises: On what “level of program(s) or

activities” should the evaluation focus? The answer is: The number and type of programs and activities included

in a process evaluation will depend on the interests and questions of stakeholders and the intended uses of the

information.

For example, if the objective of a process evaluation is solely to assess the eorts of a particular program (e.g.,

eorts to increase the cigarette tax or increase use of a quitline), and to improve that program, then a process

evaluation will gather information related only to that program. On the other hand, if the purpose of a process

evaluation is to assess comprehensive tobacco control eorts within a community, a state, or some other

geographic region, then a process evaluation will gather information related to all of the varied programs in

the specied geographic area. As another example, a number of states have already passed smoke-free work

place laws; thus the objective of a process evaluation might be to assess the education, training, and technical

assistance provided to interpret and implement these laws.

2.3 Purposes: How Does Process Evaluation Serve You?

Process evaluation has four primary purposes related to individual programs and to the general eld of

tobacco control: program monitoring, program improvement, development of eective program models, and

accountability. This section provides a brief overview of these purposes, along with case examples. Later in this

manual, you will nd more examples, as well as details on the information you can collect to fulll these purposes.

4

Section 2—Purposes and Benets of Process Evaluation

2.3.1 Program Monitoring

Program monitoring includes tracking, documenting, and summarizing the inputs, activities, and outputs of your

program. So, for example, you may record at one or more points in time:

• How much money is spent,

• The number of sta and/or volunteers involved in the activities of the program,

• The amount and types of activities related to tobacco use prevention and control,

• The number or proportion of people reached,

• The economic, social, and demographic characteristics of people reached, and

• The number of meetings or training sessions conducted.

Second, program monitoring includes the description of characteristics of the program and its context, which

might be important for understanding how and why it worked the way it did. For example, you might note:

• The locale where a program carries out its activities (e.g., rural, urban),

• Demographic or economic characteristics of the target population of the program,

• Amount of training that sta received,

• Age of the program at the time of the evaluation, and

• Unique events that occurred during the course of a program’s eorts.

Careful, reliable monitoring of the inputs, activities, and outputs of your program—along with a description of

the program’s characteristics and context—provides the basic, elemental data necessary for process evaluation.

Such information enables you to determine what you are doing; you can use this information on its own, and

you can use it in connection with the other three purposes of process evaluation or link it with outcomes.

Later, we discuss specic data that process evaluations usually collect for program monitoring. Note, however,

that no hard and fast rules apply to the selection of data to collect. The information that you need will depend on

the questions you want to answer.

2.3.2 Program Improvement

Once you have information about inputs, activities, and outputs, along with information on the characteristics

and context of a program, you can use this information to support decisions regarding program improvement or

future planning.

Consider the example of a quitline program. For those individuals who actually make contact and complete

the program, it may be achieving good quit rates. However, suppose the program suers from insucient

recruitment and retention of participants. Process evaluation can reveal why participation levels fall short

of program objectives. For instance, results may show that the program has some inconvenient features,

5

Introduction to Process Evaluation in Tobacco Use Prevention and Control

lacks optimal language or cultural attributes, or has other characteristics that create barriers. You and your

fellow program managers can then use these ndings to improve the quitline by increasing participation and

completion.

In using process evaluation for program improvement, you will most commonly approach your task in either or

both of two ways:

a. Comparing a program to a standard or expectation (e.g., program goals/objectives, funding

recommendations and guidelines, or standards of practice).

You can compare any of the data that you obtain in a process evaluation to the specic goals or objectives

of your program. For example, you may have targets regarding the number or type of people you will reach

or the amount of service that you will provide. Process evaluation will show whether you are meeting those

targets; if not, you can adjust your eorts accordingly.

Process information (e.g., information on the types of persons reached by the program, languages spoken,

features of the program) can help you understand whether you are reaching specic populations. Process

information can also support your decision-making regarding the best ways to adapt or ne tune the

program to appeal to the broadest array of persons in the intended population.

“Evidence-based” or “best practice” standards

1,6

sometimes exist for a program. When they do, you can

compare your performance to these standards, using process evaluation information. (This is sometimes

called assessing “delity” to established practice standards.) If you discover a lack of alignment with

established standards or guidelines, you can adjust your program for a better t. In the absence of standards

derived from evidence-based research, normative standards can be developed based on the experience of

programs of a similar type. For example, if you are planning a print media campaign, you may learn from

other programs that multi-media campaigns are more eective than print media alone.

b. Relating process data to outcome data.

Program outcome data enable you to know whether you are producing the desired eects. You can examine

your outcome evaluation data and process evaluation data together to identify steps you can take to

increase eectiveness.

In fact, process evaluation is most eective when implemented in conjunction with outcome evaluation.

Knowing what actually occurred as the program was implemented helps you to understand and analyze the

conditions that are responsible for a given outcome. Ideally, process evaluation will allow you to attribute

strengths and/or weaknesses of your program to specic program characteristics or activities. Without this

information, you may nd it very dicult to take action when attempting to improve the program using

only outcome information.

8

6

Section 2—Purposes and Benets of Process Evaluation

2.3.3 Building Eective Program Models

The experiences of multiple programs have shown that the tobacco control eld can use process and outcome

information jointly to build eective program models. Evaluation research can identify, for example, which

activities tend to lead to the best outcomes. This use of process evaluation typically lies outside the purview

of a single program, unless that program is large enough to vary its activities systematically and test how that

variation aects outcomes. More commonly, individual programs will simply report their process and outcome

data to CDC/OSH or in annual reports; or they might participate in a controlled or natural eld experiment.

Controlled scientic experiments to validate evidence-based practices can incorporate process evaluation for

multiple functions. For example, documentation of inputs and activities produces information for comparing

the extent to which experimental and control programs have carried out their work in conformity with

study protocols. Accurate recording of outputs enables researchers to compare the relative productivity of

experimental and control programs. Documentation of activities, as well as unique occurrences that aected

a specic program, can assist in the interpretation of experimental data, in the explanation of anomalies, and

in decisions concerning validity of specic cases to be included in the analysis of an experiment’s ndings. See

also Steckler and Linnan (2002)

9

for a discussion of process evaluation in the development of theory-based

interventions.

2.3.4 Accountability

Process evaluation assists a program in being accountable to its funders, regulators, and other stakeholders,

including government ocials and policy makers. It does so, rst of all, by providing the data necessary to justify

expenditures of time and money—for example, demonstrating the number of materials produced, the amount

of public advertising, the number of people reached or served, and so forth. A clear demonstration of the links

between program inputs, activities, and outcomes enhances justication for funding.

Second, process evaluation supports accountability by documenting compliance with externally imposed

standards

1

or criteria established by program funders for continued funding of the program. For example,

process evaluation can indicate whether stang for a program meets the level recommended by CDC.

See Exhibit 2-1 for more information on the purposes of process evaluation and examples of questions that

process evaluation enables you to answer.

1

These standards are often based on research that has established evidence-based practice, but not necessarily.

7

Introduction to Process Evaluation in Tobacco Use Prevention and Control

Exhibit 2-1: Four Primary Purposes of Process Evaluation

What You Can Do with Process

Evaluation Purpose Sample Questions

1. Program

monitoring

Track, document, and summarize the

inputs, activities, and outputs of a

program.

Describe other relevant characteristics

of the program and/or its context.

• How much money do we spend on this

program?

• What activities are taking place?

• Who is conducting the activities?

• How many people do we reach?

• What types of people do we reach?

• How much eort (e.g., meetings, media

volume, etc.) did we put into a program or

specic intervention that we completed?

2. Program

improvement

Compare the inputs, activities, and

outputs of your program to standards

or criteria, your expectations/plans, or

recommended practice (delity).

Relate information on program inputs,

activities, and outputs to information

on program outcomes.

• Do we have the right mix of activities?

• Are we reaching the intended targets?

• Are the right people involved as partners,

participants, and providers?

• Do the sta/volunteers have the necessary

skills?

3. Building

eective

program models

Assess how process is linked to

outcomes to identify the most

eective program models and

components.

• What are the strengths and weaknesses

within discrete components of a multi-

level program?

• What is the optimal path for achieving a

specic result (e.g., getting smoke-free

regulations passed)?

4. Program

accountability

Demonstrate to funders and other

decision makers that you are making

the best possible use of program

resources.

• Have the program inputs or resources

been allocated or mobilized eciently?

In the following case examples, tobacco control professionals have found process evaluation useful for assisting

with practical issues they face in implemen

ting high quality programs. (Note that these case examples, as well as

the others later in this manual, are tied to specic parts of a logic model and/or to the categories of information

typically gathered in a process evaluation. This link to the model is intended to strengthen the use of process

evaluation within the overall CDC approach to evaluation.)

8

Section 2—Purposes and Benets of Process Evaluation

CASE EXAMPLE BASED ON LOGIC MODEL CATEGORY: ACTIVITIES

Assessment of Learning from truth

®

: Youth Participation in Field Marketing Techniques to Counter

Tobacco Advertising

The truth

®

campaign, a mass-media (print and television) counter-marketing activity targeting youth age

12-17, was funded by the American Legacy Foundation and included a national eld marketing component

(the truth

®

tour). This unique campaign promotes an “edgy youth” brand and provides information about

tobacco, the tobacco industry, and the social costs of tobacco use. It advocates that teens take control of

their lives and reject the inuence of the industry’s advertising practices.The goal is to reach non-mainstream

teens, a group that evidence shows to be at risk for smoking initiation, by using youth who reect the target

audience to sta a eld marketing endeavor.”

How process evaluation was helpful:

The tour was designed to encourage direct youth-to-youth contact to facilitate the transmission of

tobacco counter-marketing information. This unique approach posed several problems for a traditional

outcome evaluation design. The age of the target audience precluded follow-up interviews without

parental permission, so an ethnographic approach was used to provide process evaluation data instead.

Methods consisted of observation, participant-observation, informal conversations, and semistructured and

unstructured open-ended interviews with the tour riders, sta, and adults from the visited communities.

The purpose of the evaluation was program improvement. Data were needed to document tour activities and

group dynamics, and to assess the impact of tour participation on the riders. Riders consisted of three groups

of between 6 and 12 carefully selected, diverse, and specially trained youth (under the age of 18) who visited

27 cities in 2000. The tour created three small, close-knit mobile communities who lived and worked together

for a 6-week period. The tour was built around high visibility trucks painted with the truth

®

logo and specic

music geared to appeal to the targeted audience in selected venues. To avoid undermining the edgy youth

image, no one from the local markets was involved in the planning or implementation of tour activities.

Advantages for you:

The evaluation provided an opportunity to assess the implementation of a unique eld marketing approach

to reaching teens with a public health message about tobacco use. Evaluation results highlight various

lessons learned. The evaluation provided an in-depth understanding of the range and type of diculties

associated with underage, “edgy” culturally diverse riders. A possible alternative would be to hire young

adults who do not need to be supervised as closely while on the road and to involve youth from local markets

in the planning and implementation of the activity. The latter would address the problems that occurred

with visiting venues where none of the target audience appeared. Sensitivity training around issues of race,

ethnicity, sexual preference, and youth culture is required for all adult sta when traveling on the road with

diverse youth. Evaluation results also suggest that eld marketing techniques for a national social marketing

campaign can benet from involvement of a local distribution system for the product or message, in order to

create linkages that might sustain brand visibility and product availability in the community. Closer ties with

local level tobacco control allies who reect the image of the campaign would be a more eective strategy.

SOURCE: Eisenberg M, Ringwalt C, Driscoll D, Vallee M, Gullette G. Learning from truth®: Youth

participation in eld marketing techniques to counter tobacco advertising. Journal of Health

Communication 2004; 9:223-231.

(Continued)

9

Introduction to Process Evaluation in Tobacco Use Prevention and Control

CASE EXAMPLE BASED ON LOGIC MODEL CATEGORY: ACTIVITIES and OUTPUTS

Outcome and Process Evaluation of a School-Based, Informal, Adolescent Peer-Led Intervention to

Reduce Smoking

Peer education as a strategy for youth health promotion is used extensively, although there is mixed evidence

for its eectiveness. There are few systematic accounts of what young people actually do as peer educators. To

examine the activities of the young people recruited as “peer supporters” for A Stop Smoking in Schools Trial

(ASSIST) in southeast Wales and the West of England, 10,730 students in 59 secondary schools were recruited

at baseline. The ASSIST peer nomination procedure was successful in recruiting, training, and retaining

inuential year 8 peer supporters of both genders to intervene informally to reduce smoking levels in their

year group.

How process evaluation was helpful:

Outcome data at 1-year follow-up showed that the risk of students who were occasional or experimental

smokers at baseline reporting weekly smoking at follow-up was 18.2% lower in the intervention schools.

This result was supported by analysis of salivary cotinine. To understand how this short-term outcome was

achieved, researchers assessed qualitative data from the process evaluation. These data showed that the

majority of peer supporters adopted a pragmatic strategy: they concentrated their attention on friends and

peers who were occasional or non-smokers and whom they felt could be persuaded not to take up smoking

regularly, rather than those they considered to be already “addicted” or who were members of smoking

cliques.

Advantages for you:

By combining process and outcome evaluation, the authors were able to identify how the peer supporters

actually implemented the intervention to achieve the outcome. The study showed that school-based peer

educators are eective in diusing health promotion messages when they are asked to work informally

rather than under the structured supervision of teaching sta. The smoking behavior of the peer supporters

themselves also appears to have been aected by the training. Though not encouraged to use fear-based

approaches (as best practice would suggest) the peer educators actually employed such tactics eectively.

While the message delivered by the peer educators was relatively unsophisticated and soon appeared to lose

momentum, a two-year follow-up will substantiate whether the reduction in smoking levels is maintained.

SOURCE: Audrey A, Holliday J, Campbell R. It’s good to talk: Adolescent perspectives of an informal,

peer-led intervention to reduce smoking. Social Science and Medicine 2006;63:320-334.

10

Section 2—Purposes and Benets of Process Evaluation

2.4 Users and Uses of Process Evaluation Information

2.4.1 Users

There are three major groups of stakeholders integral to program evaluation:

• Those served or aected by the program, such as patients or clients, advocacy groups, community members,

and elected ocials;

• Those involved in program operations, such as management, program sta, partners, the funding agency or

agencies, and coalition members; and

• Those in a position to make decisions about the program, such as partners, the funding agency, coalition

members, and the general public.

A primary feature of an eective evaluation is the identication of the intended users who can most directly

benet from an evaluation.

8

A rst step should be to identify evaluation stakeholders, including those who

have a stake or vested interest in evaluation results, as well as those who have a direct or indirect interest in

program eectiveness.

8

Identication and engagement of intended users in the evaluation process will help

increase use of evaluation information. These intended users are more likely to understand and feel ownership

in the evaluation process if they have been actively involved in it.

8

Additionally, such engagement enhances

understanding and acceptance of the utility of evaluation information throughout the lifecycle of a program. So,

to ensure that information collected, analyzed, and reported successfully meets the needs of stakeholders, you

should work with the people who will be using this information from the beginning of the evaluation process

and focus on how they will use it to answer what kind of questions.

The following are possible stakeholders in tobacco prevention and control programs:

• Program managers and sta

• Local, state, and regional coalitions interested in reducing tobacco use

• Local recipients of tobacco-related funds

• Local and national partners (such as the American Cancer Society, the American Lung Association,

the American Heart Association, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the American Legacy

Foundation, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, and the Robert Wood Johnson

Foundation)

• Funding agencies, such as national and state governments or foundations

• State or local health departments and health commissioners

• State education agencies, schools, and educational groups

• Universities and educational institutions

• Local government, state legislators, and state governors

11

Introduction to Process Evaluation in Tobacco Use Prevention and Control

• Privately owned businesses and business associations

• Health care systems and the medical community

• Religious organizations

• Community organizations

• Private citizens

• Program critics

• Representatives of populations disproportionately aected by tobacco use

• Law enforcement representatives

As you review this list, consider that many of these stakeholders have diverse and, at times, competing

interests. Given that a single evaluation cannot answer all possible issues raised by these diverse interests,

the list of stakeholders must be narrowed to a more specic group of primary intended evaluation users; the

recommended number of primary intended evaluation users is 8-10.

10

These stakeholders/primary intended

users will serve in advisory roles on all phases of the evaluation, beginning with identication of primary

intended uses of the evaluation (see Section 4).

To identify the primary intended users, you and your program collaborators should identify all possible

stakeholders and determine how critical it is for the ndings of the evaluation to inuence each stakeholder.

Only those stakeholders whom you want to be inuenced and to take action (as opposed to those for whom

information is valuable to know, but not critical) should be included as primary intended users.

12

Section 2—Purposes and Benets of Process Evaluation

CASE EXAMPLE BASED ON LOGIC MODEL CATEGORY: INPUTS

Stakeholder Advisory Board

The North Carolina Youth Empowerment Study

The North Carolina Youth Empowerment Study (NC YES) was a three-year participatory evaluation of youth-

based tobacco use prevention programs. The study aimed to document the characteristics of youth tobacco

use and prevention programs throughout North Carolina, and to track the role youth in these programs

played in implementing tobacco-free policies within local school districts.

How process evaluation was helpful:

One important component of the project involved convening an advisory board of key program stakeholders,

including both youth and adults. The purpose of the advisory board was to provide input on all aspects of

the study, including the study’s research questions, data collection strategies, and interpretation of results.

Board members were selected to reect the racial, ethnic, and geographic diversity of the state, as well as the

diversity within types of participating organizations.

Advantages for you:

The benets of this collaboration were apparent to both researchers and stakeholders who were members of

the advisory board. For example, the research team was able to use the board’s input on the data collection

tools so that the information collected would be of greater use to the community. The board also requested

that the research team disseminate results beyond the university so that a wider audience would have access

to the ndings. Being involved in the process beneted board members through increased knowledge of

evaluation and research methods. They also felt that their experiences and skills had been utilized through

the participatory process and that the information disseminated beneted multiple audiences, not just the

research community.

SOURCE: Ribisl KM, Steckler A, Linnan L, Patterson CC, Pevzner E, Markatos E, et al. The North Carolina

Youth Empowerment Study (NC YES): A participatory research study examining the impact of

youth empowerment for tobacco use prevention. Health Education & Behavior 2004;31(5):597–614.

13

Introduction to Process Evaluation in Tobacco Use Prevention and Control

CASE EXAMPLE BASED ON LOGIC MODEL CATEGORY: ACTIVITIES

Assessing the Eectiveness of a Training Curriculum for Promotores, Spanish-Speaking Community

Health Outreach Workers

Tobacco Free El Paso’s objective was to recruit and train promotores who would deliver comprehensive

tobacco cessation interventions (including free nicotine replacement therapies) to low-income,

predominantly Spanish-speaking populations of smokers. Although promotores are used along the U.S.-

Mexico Border to conduct health education classes on topics related to diabetes and other health-related

conditions, there is no research on what role they can play as tobacco cessation counselors.

How process evaluation was helpful:

The training courses (each of which lasted ve days) oered three levels of certication: an introductory basic

skills level; intermediate treatment specialist; and, advanced “leave the addiction” specialist. Over a one-year

period (August 2003–August 2004), 24 training courses involving 89 participants were delivered. Process

information was obtained on the 74 participants who were certied for the introductory level. Of these, 39

went on to the intermediate level and 34 to the advanced certication. To determine the course’s eect on

self-condence and satisfaction, participants were given pre- and post-test measures. While self-condence

improved in all participants, those who completed all the three levels showed the most signicant increase

and were judged capable of delivering a brief smoking cessation intervention. High satisfaction scores

indicated that participants felt adequately prepared.

Program sta used this information to validate the program’s success and to improve implementation of their

“train the trainer” model. The fact that the training courses were easily accessible and free of charge increased

attendance. But the length of the course had a deterrent eect as indicated by the smaller number who

completed the higher levels of training. As a result, the 5-day training session was shortened to 1-, 2-, and

3-day sessions in order increase the number of participants who advance to the higher training levels. This

change was necessary to accommodate participants’ diverse work schedules.

Advantages for you:

Promotores who successfully completed the entire program became part of an extended “train the trainer”

team, with the intention of producing broad population change, and reducing disparities for low-income,

Spanish-speaking people in El Paso. Program sta used the process information to rene the program’s

activities and maximize the number of promotores who would undergo the full training program. Similarly,

you can monitor activities, record participation, and assess satisfaction in order to adjust programs

systematically to eliminate problems that might be reducing your eectiveness.

SOURCE: Martinez-Bristow Z, Sias JJ, Urquidi U, Feng C. Tobacco cessation services through community

health workers for Spanish-speaking populations. American Journal of Public Health, Field Action

Report 2006;96(2): 211-213.

2.4.2

Users

As discussed earlier in this chapter, process evaluations can serve a variety of purposes and can be useful in

dierent ways. Below are two examples of how ongoing process evaluations were used to improve program

guidance and programmatic activities.

14

Section 2—Purposes and Benets of Process Evaluation

CASE EXAMPLE BASED ON LOGIC MODEL CATEGORY: INPUTS

Assessment of Use of Best Practices Guidelines by 10 State Tobacco Control Programs

The Best Practices for Comprehensive Tobacco Control Programs developed by CDC/OSH in 1999 was the rst

national resource to dene the required components of a comprehensive tobacco control program. The

guidelines provide a framework for planning and implementing tobacco control activities. The questions

addressed in the qualitative process evaluation were whether and how states used the guidelines in their

program planning, and what strengths and weaknesses of the guidelines could be identied. During

2002-2003, process evaluation data were collected and analyzed from 10 state tobacco control programs

on familiarity, funding, and use of the guidelines. Information was obtained through written surveys and

qualitative interviews with key tobacco partners in the states. The typical number of participants interviewed

was 17, representing an average of 15 agencies per state.

How process evaluation was helpful:

The results showed that lead agencies and advisory agencies were most familiar with the guidelines, while

other state agencies were less aware of them. Most states modied the guidelines to develop frameworks that

were tailored to their context. For example, many states prioritized the nine components and expenditures

according to their own available resources because funding levels were not always realistic.

Advantages for you:

The results show that the strength of the guidelines included providing a basic framework for program

planning and specic funding recommendations. Limitations included the fact that the guidelines did not

address implementation strategies or tobacco-related disparities, and had not been updated with current

evidence-based research. To ensure that the guidelines continued to be useful to the states, the evaluators

recommended that the guidelines be updated to address implementation of program components,

identify strategies to reduce tobacco-use disparities, and include evidence-based examples. Recommended

funding levels also need to be revised to be more eective in changing social and political climates, and, the

guidelines need to be disseminated beyond typical lead agencies to other tobacco control partners, such as

coalitions and relevant state agencies.

SOURCE: Mueller N, Luke D, Herbers S, Montgomery T. The best practices: Use of the guidelines by ten

state tobacco control programs. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 2006;31(4).

15

Introduction to Process Evaluation in Tobacco Use Prevention and Control

CASE EXAMPLE BASED ON LOGIC MODEL CATEGORY: ACTIVITIES

Incorporating Process Evaluation Findings into Development of a Web-Based Smoking Cessation

Program for College-Aged Smokers

College-aged smokers often do not use traditional cessation methods, such as support groups and

counseling, to reduce their levels of smoking. Therefore, this study aimed to explore the option of an Internet-

based cessation intervention, Kick It!, designed especially for college students. The purpose of the study

was to develop the system and conduct a process evaluation to understand usage and acceptability of the

intervention, as well as to obtain other feedback.

How process evaluation was helpful:

Thirty-ve smokers participated in the intervention, and the research team conducted qualitative interviews

with 6 of the 35 students. The interviews were designed to obtain more information on student use of the

Kick It! program, their thoughts on the program’s strengths and weaknesses, and their recommendations for

future change. The in-depth interviews uncovered several useful suggestions for adding components to the

program, creating a more personalized system, and making format and content changes.

Advantages for you:

The information collected from respondents was detailed enough to allow Kick It! developers to improve

the program for future users and for other researchers to review the work conducted through this process

evaluation to inform development of similar programs for college-aged students.

SOURCE: Escoery C, McCormick L, Bateman K. Development and process evaluation of a Web-based

smoking cessation program for college smokers: Innovative tool for education. Patient Education

and Counseling 2003; 53:217–5.

16

Section 3—Information Elements Central to Process Evaluation

3. INFORMATION ELEMENTS CENTRAL TO PROCESS EVALUATION

3.1 Indicators of Inputs/Activities/Outputs

In a process evaluation, you will collect indicators related to the rst three categories of an evaluation logic

model (inputs, activities, and outputs):

2

• Input indicators measure the various resources that go into a program. Inputs for a tobacco control program

can relate to stang, funds, and other resources.

• Activity indicators measure the actual events that take place as part of a program. In tobacco control, these

events could include youth education campaigns, messages delivered via the media, coalition development,

and many other types of eorts.

• Output indicators measure the direct products of a program’s activities. Examples include the number of

participants using a smoking quitline, a completed media campaign, a higher cigarette tax, the number of

posters placed in stores and buses, and other products.

The following table (Exhibit 3-1) lists typical information elements gathered through process evaluation,

describes them, and provides examples of measures or indicators

2

that can provide this information. The rst

three sets of information elements appear within the categories of inputs, activities, and outputs. Next, some

additional information elements that relate holistically to the overall program and/or its context are listed.

Note that the types of information you collect will depend on the program’s objectives and should be related

to the questions the process evaluation will address. For example, it is typically very important to obtain

information on the characteristics of persons reached or otherwise aected by your program or policy/

regulations. However, which characteristics will you choose to monitor? Gender? Ethnicity? Age? In designing

your process evaluation, the characteristics you select to measure will depend on your specic information

needs. So, for example, if an evidence-based program applies only to a specic age group, you will want

to measure age; or if you need to understand dierences in outcomes among persons of dierent ethnic

backgrounds, then you will want to measure ethnicity.

2

In some cases, a single information element constitutes an indicator on its own (e.g., the number of sta ). In other cases, two

or more elements combine to make a meaningful indicator (e.g., dollars spent per capita).

17

Introduction to Process Evaluation in Tobacco Use Prevention and Control

Exhibit 3-1: Information Commonly Obtained in a Process Evaluation

Item Description Example Process Indicators

1

Inputs

Financial Revenues to support prevention and

control activities, by source; costs

(total or specic to each activity)

Expenses for sta, supplies, media, etc.

Dollars spent per capita

Sources of funds

Personnel—

Quantity

The number of paid sta and/or

volunteers involved;

hours of paid sta and volunteers

Number of sta who carry out the prevention/

control activities

Hours of eort to produce a product

Personnel—

Professional

Characteristics

Qualications/experience/ training of

sta/volunteers involved

Number of sta with special certication

Educational background of sta and

volunteers

Personnel—

Personal

Characteristics

Individual characteristics of sta/

volunteers involved

Ethnic background of sta

Age of sta

Gender of sta

Facilities Key characteristics of the building(s)

and equipment

Hours of operation

Accessibility

Technological capability

Locale Location where the initiative occurs or

the program operates

Geographic scope of prevention/control

activities

Neighborhood type (e.g., urban)

Activities

Population-

oriented

prevention activity

Description of activities to discourage

use or exposure voluntarily, or to

eliminate use or exposure legally—

focused on the community or a

segment of the community

Whether and how counter-marketing occurs

Whether and how information is presented to

legislators

Whether and how technical assistance is

provided to agencies

Individual-

oriented activity

Description of activities directed

toward individuals, on an individual

basis or in dened groups

Type of training

Type of counseling

Accessibility Characteristics of the program that

facilitate exposure to the intervention

Language of campaign materials

Time of day that program is oered

Languages spoken by sta and/or volunteers

Proximity to mass transit

Recruitment Processes for identifying,

approaching, and engaging targeted

audience

Type of contact

Means of advertising

Incentives used to engage audience

18

Section 3—Information Elements Central to Process Evaluation

Exhibit 3-1: Information Commonly Obtained in a Process Evaluation (continued)

Item Description Example Process Indicators

Outputs

Persons reached The number of people with

documented exposure to messages or

who participate in prevention/control

activities

Number of people reached

Number of class participants

Characteristics of

persons reached

Demographic, family, personal,

health, and other attributes of the

people reached by prevention/control

activities

Age

Gender

Comparison of characteristics of persons

reached with characteristics of the intended

target population

Products resulting

from prevention/

control activities

Amount of messages, public

meetings, advertisements,

promotional segments in TV, radio,

newspapers; and, if applicable, service

units delivered

Number of advertisements

Amount of donated air time

Number of meetings with legislators

Number of course sessions

Number of public meetings

Gross Rating Points (GRPs)

Documents that

inuence tobacco

control in a target

area

Written plans, guidelines, or other

documents that inuence the pattern

of tobacco control activities (systems,

partnerships, campaigns, service

delivery) within a target area

Completed state plan

Other Elements Relating to an Initiative/Program as a Whole or to its Context

Developmental

stage

Description of program’s maturity/

current stage of activities

Stage, e.g.:

• Formative/planning

• Early implementation

• Established but still being modied

• Established but stable

• In decline

Organizational

structure and

components

Description of the makeup of the

organization, task force, coalition,

etc., that oversees and implements

program activities, including

accountability for distinct activity

modules, as well as other relevant

structural, leadership, service delivery,

and/or administrative processes

• Name(s) of organization(s) involved,

overall and for each major portion of the

activities

• Aliations of managers

• Type of inter-agency agreement, if any

(Continued)(Continued)

19

Introduction to Process Evaluation in Tobacco Use Prevention and Control

Exhibit 3-1: Information Commonly Obtained in a Process Evaluation (continued)

Item Description Example Process Indicators

Program theory

and delity

Presence or absence of elements/

characteristics of tobacco prevention/

control activities that have been

specied through previous research,

guidelines, and the development of

protocols

• Checklist of steps or guidelines specied

in best practice instructions

• Chronology of signicant implementation

actions

• Identication of events that interfered

with planned activities or implementation

of activities

Collaborations/

partnerships

Extent to which a program involves

multiple independent agencies joined

in a formal arrangement and mutually

accountable for all or part of the work

• Membership lists

• Inter-agency agreements

• Roles of each partner

• Survival of the collaboration for the

duration of the activities

Social, political,

economic

environment

in area of focus

for the tobacco

prevention/

control activities

Elements of the social, political, and

economic conditions that aect the

planning, implementation, and/or

evaluation of the activities intended

to be implemented by a program

• Opinions about tobacco control in

legislature or among the general public

• Major economic trends in area

• Legislation/regulations that enhance

or impede tobacco prevention/control

activities

• Tobacco industry activities and

promotions

Other unique

occurrences

Events within or outside of a program

that aect its implementation or

ongoing operations

• Disruptive social, historical, or

environmental events that inuence

program activities, accessibility, or reach

• Delays in acquisition of nancial

resources, sta, equipment, etc.

20

Section 3—Information Elements Central to Process Evaluation

3.2 Comparing Process Information to Performance Criteria

The specic information elements you collect will depend both on the type of tobacco prevention/control

activities you intend to implement as well as the questions you need to answer through your process evaluation.

As mentioned earlier, process information, in and of itself, is neutral. It does not indicate quality, delity, success,

or compliance. However, you can use process information to assess your progress, provided you establish a

standard or a criterion with which to compare that information.

A standard upon which to compare the process information can be established by using one or more of the

following types of criteria:

• Performance criteria from a funder (e.g., CDC program announcement, foundation RFP);

• Criteria developed as part of the program planning and development process (e.g., SMART objectives,

strategic plan);

• Criteria developed as part of the evaluation planning process (e.g., by an evaluator in consultation with

program sta or a diverse group of stakeholders such as a subgroup of the tobacco control coalition).

Each of these approaches should be supported by scientic guidance of evidence-based programming such

as Best Practices for Comprehensive Tobacco Control Programs,

1

The Guide to Community Preventive Services,

6

and

Communities of Excellence in Tobacco Control.

7

In addition, such criteria should be reasonable within the local

context.

To briey illustrate how process indicators can be compared to hypothetical criteria, we present example inputs,

activities, and outputs that were gathered through eld interviews during full-day site visits with nine states,

discussion groups with state tobacco control sta nationwide, and literature reviews. These are examples of the

inputs, activities, and outputs identied as key elements of comprehensive tobacco use prevention and control

programs.

The comparison of actual inputs, activities, and outputs (as measured through process evaluation) to established

criteria can assist state and territorial tobacco control managers in:

• Identication of discrepancies between planned and actual implementation of the program or intervention;

• Identication of eective and ineective implementation and management strategies; and,

• Improved understanding of whether and how program activities contribute to achieving desired short-term

outcomes.

21

Introduction to Process Evaluation in Tobacco Use Prevention and Control

In Exhibits 3-2, 3-3, and 3-4, we provide examples of how process information can inform decisions about

programmatic issues such as these. It is very important to note that these are merely examples for you to

consider in developing your own criteria and indicators, and they should not be considered as recommended by

CDC for adoption.

Exhibit 3-2 lists example inputs, example criteria for measuring these against, and example indicators for

measuring them.

Exhibit 3-2: Inputs—Comparing Indicators to Criteria

Type of Input Example Criteria

Example Input Indicators

Funding

CDC-r

ec

ommended levels per Best Practices

guidelines

Dollars allocated for each program

component

Stang Required or recommended stang as

described in CDC funding opportunity

announcement (FOA)

Actual stang

Sta Skills 50% of sta will be trained in cultural

competence and 85% will of those trained

will assess the training as high quality

Percentage of sta trained in cultural

competence, and percentage who assess

training as high quality

Partnerships 75% of partners perceive the state as

inclusive of their views in its planning and

implementation

Survey/interview data on partners’

perceptions of the degree to which the

state is inclusive of their views in its

planning and implementation

Specic community or statewide initiatives or programs will select activities that they feel best t the population

they want to address with the nancial resources available, and with respect to political, social, and cultural

considerations. Activities they might select appear in the rst column of Exhibit 3

-3. Please note that these

activities may be carried out by NTCP grantees, partners collaborating with the grantees, or partners on their

own.

For each activity implemented, outputs can also be measured. If output standards exist or are developed, you

can c

ompar

e actual outputs to expected outputs. Example activities with corresponding outputs, including

example criteria and indicators for each, are listed in Exhibit 3-3. While Exhibit 3-1 provides a description of

some of these types of activities, the following criteria contain evaluative components. This ensures that the

information gathered includes not only a description of the activity, but also an assessment of the quality of

that activity. In the rst example (i.e., counter-marketing), the output not only includes the percentage of the

population reached, but also an assessment of the cultural appropriateness of the message.

22

Section 3—Information Elements Central to Process Evaluation

In order to clarify how to understand and use Exhibit 3-3, the following example related to counter-marketing

is provided.

A state health department conducted an evaluation survey and found that compared to other

groups, African-Americans were less likely to report having smoke-free home and automobile

rules, and their children were more likely to be exposed to secondhand smoke. To address

these disparities, the tobacco foundation in the state provided a grant to conduct a multi-

channel counter-marketing campaign to inuence knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors of

African-Americans related to secondhand smoke exposure. Results of a process evaluation

of the counter-marketing campaign showed that it was implemented in print and radio,

and TV via public service announcements (PSAs) rather than paid spots. When planning the

campaign, the state established the criteria that 75% of African-American adults will recall

the campaign messages and perceive them to be appropriate for their community. In order

to evaluate the eectiveness of the campaign, the state contracted with an evaluator to work

with the local association of African-American churches to conduct an evaluation. Evaluation

components included a brief written survey of a random sample and four discussion groups

with church members. Results showed that 45% of those surveyed could recall the messages

and that the messages were most frequently heard on the radio. Discussion group results with

church members who had seen the campaign showed that 90% of them felt the messages

were appropriate for their community. Consequently, the state determined that for the next

counter-marketing campaign, they would not only implement the campaign using TV, radio

and print, but that the emphasis would be on radio spots. Additionally, to evaluate outcomes,

the state planned to include questions assessing exposure to the ads and changes in attitudes

and behavior in a subsequent population-based evaluation survey.

In analogous fashion, you can compare information on program activities with criteria for

understanding the capacity of interventions to identify and eliminate tobacco-related disparities. In

Exhibit 3-4, we provide several examples of activity and output criteria and process indicators. Again,

it is important to note that these are provided as illustrative examples only, and do not represent

programmatic guidelines from CDC on inputs, activities, outputs, criteria, or indicators.

23

Exhibit 3-3: Activities and Outputs—Comparing Indicators to Criteria

Type of

Activity

Counter-

marketing

Policy and

regulatory

action

Community

mobilization

School-based

prevention

Activity

Example Criteria Example Indicators

Implementation of a culturally

appropriate multi-channel media

campaign (TV, radio, and print)

encouraging African Americans

to develop smoke-free home and

automobile rules

Description of whether and

how counter-advertising

campaign is implemented

Collaboration with governmental

agencies and partners to

develop a comprehensive plan

to carry out smoke-free law

implementation (e.g., signage,

educating businesses)

Description of process

used to develop plan (e.g.,

identication of stakeholders,

steps taken to develop plan)

Minimum of 6 earned

media spots, quarterly press

conferences, and press releases

on current policy and regulatory

issues (e.g., taxation, secondhand

smoke policy)

Number of media spots, press

conferences/press releases,

and topics addressed

Provision of appropriate, timely

and useful technical assistance to

all local partners

Description of whether and

how technical assistance is

provided to local partners

Complete an assessment of

the existence of and perceived

compliance with tobacco-free

school policies

Description of whether

tobacco-free school policies

are in place and perceptions

of compliance

Output

Example Criteria Example Indicators

75% of African-American

adults recall the campaign

messages about secondhand

smoke exposure in homes

and automobiles and perceive

them as appropriate for their

community

Percentage of African-

Americans that recall

campaign messages

and perceive them to

be appropriate for their

community

Quality written comprehensive

implementation plan completed

in collaboration with appropriate

government agencies and

partners

Appropriate external

secondhand smoke

policy experts assess

implementation plan as

high quality

Quarterly newspaper articles

and editorials as a result of press

conferences and press releases

Frequency of articles and

editorials that reference

materials or information

provided in the press

release and/or press

conference

85% of local partners assess

technical assistance as

appropriate, timely, and useful

Percentage of local

partners that assess

technical assistance as

appropriate, timely and

useful

75% of school districts respond

to the survey of tobacco-free

school policies and data are used

to develop an action plan to

increase school district coverage

Response rate to

assessment and action

plan to increase school

coverage

Introduction to Process Evaluation in Tobacco Use Prevention and Control

24

Exhibit 3-4: Tobacco-Related Disparities: Activities and Outputs—Comparing Indicators to Criteria

Type of Activity Activity Output

Example Criteria Example Indicators Example Criteria Example Indicators

Partnership

development

Collaborative relationships

will be established with each

CDC funded National Network

to reduce tobacco related

disparities with their respective

priority population groups

Number of agreements

to work with the

National Networks

As a result of each collaboration,

one strategy and two opportunities

to reach and impact each priority

population will be identied and

assessed as culturally competent by

priority population representatives

Identied strategies and

opportunities assessed

by priority population

representatives as culturally

competent

Strategic plan

to address

disparities

A group composed of

appropriate and diverse

stakeholders will work to

develop a disparities strategic

plan

Evidence of

involvement of

stakeholders from

priority populations in

development of plan

A disparities strategic plan will be

developed and incorporated into

the overall strategic plan, along with

implementation strategies

Overall strategic plan,

including disparities plan

and implementation

strategies

Knowledge

integration

Using knowledge about

tobacco-related disparities,

two culturally competent

interventions will be

implemented with priority

populations

Priority populations

and interventions

identied

Two tailored population-based

interventions implemented as

designed reaching 40% of the

identied priority populations

Evaluation will show

implementation of the

interventions as designed

(i.e., delity) and percentage

of priority population

reached

Surveillance Develop and implement

surveillance systems that

are able to identify tobacco-

related disparities

Description of whether