EUROPEAN

ARREST WARRANT

PROCEEDINGS

―

ROOM FOR

IMPROVEMENT

TO GUARANTEE

RIGHTS IN

PRACTICE

REPORT

© European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, 2024

Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged.

For any use or reproduction of photos or other material that is not under the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights

copyright, permission may need to be sought directly from the copyright holders.

Neither the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights nor any person acting on behalf of the agency is responsible for the use

that might be made of the following information.

Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2024

Print ISBN ---- doi:./ TK----EN-C

PDF ISBN ---- doi:./ TK----EN-N

© Photo credits:

Cover: © Valerii Evlakhov/ Adobe Stock

Page 13: © Belish/ Adobe Stock

Page 22: © Mumtaaz Dharseypeopleimages.com/ Adobe Stock

Page 29: © zoka74/ Adobe Stock

Page 37: © Maciej Koba/ Adobe Stock (AI generated)

Page 47: © wutzkoh/ Adobe Stock

Page 65: © mojo_cp/ Adobe Stock

Page 72: © cunaplus/ Adobe Stock

Page 77: © cherdchai/ Adobe Stock

Page 81: © auremar/ Adobe Stock

Page 87: © Liubomir/ Adobe Stock

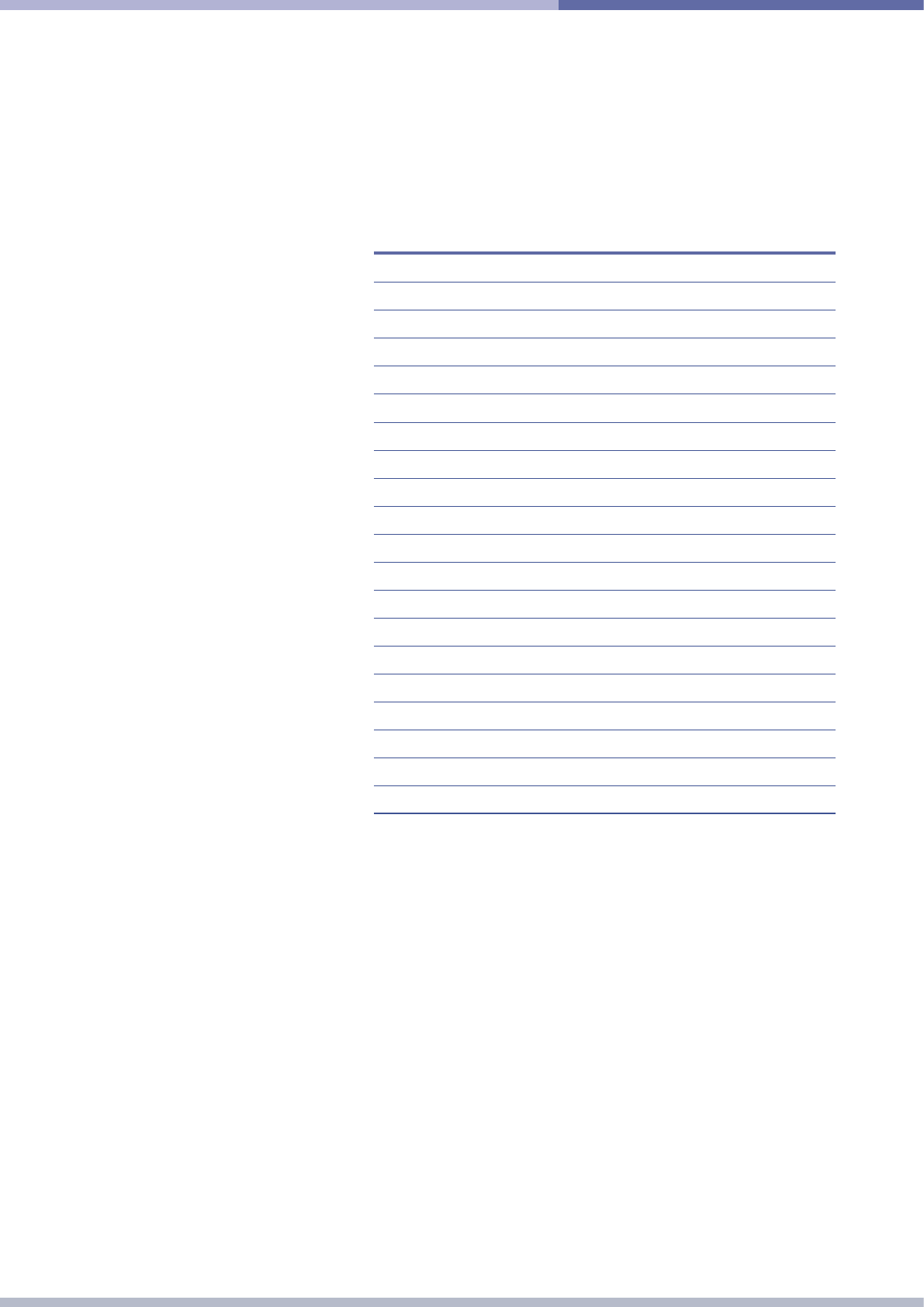

Contents

Glossary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2

Abbreviations

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .3

Country codes

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4

Key findings and FRA opinions

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .5

Introduction

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13

WHY THIS REPORT?

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

SCOPE AND PURPOSE

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

STRUCTURE OF THE REPORT

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

METHODOLOGY AND CHALLENGES

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

ENDNOTES

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

ISSUING AND EXECUTING A EUROPEAN ARREST WARRANT FOCUSING ON

PROPORTIONALITY AND FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTSBASED GROUNDS FOR NONEXECUTION . . . .

A. LEGAL OVERVIEW . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

B. FINDINGS: ISSUING AND EXECUTING A EUROPEAN ARREST WARRANT IN PRACTICE . . . . .

ENDNOTES

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

RIGHT TO ACCESS TO A LAWYER . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

A. LEGAL OVERVIEW . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

B. FINDINGS: RIGHT TO ACCESS TO A LAWYER IN PRACTICE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

ENDNOTES

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

RIGHT TO INFORMATION IN EUROPEAN ARREST WARRANT PROCEEDINGS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

A. LEGAL OVERVIEW . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

B. FINDINGS: RIGHT TO INFORMATION IN PRACTICE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

ENDNOTES

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

RIGHT TO INTERPRETATION AND TRANSLATION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

A. LEGAL OVERVIEW . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

B. FINDINGS: INTERPRETATION AND TRANSLATION IN NATIONAL LAWS AND PRACTICE . . .

ENDNOTES

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

CONCLUSION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Glossary

Accused person Any natural person who is formally charged by the competent authorities (i.e. a prosecutor,

an investigative judge or even the police) with allegedly having committed a criminal offence.

The term commonly refers to a person subject to the more advanced stages of pre-trial

proceedings and/or a person committed to trial.

Arrest An action involving the apprehension of a person suspected of being involved in a crime

by the law enforcement authorities and their being placed in police custody.

Charge An official notification given to an individual by the competent authority of an allegation

that they are suspected or accused of having committed a crime; also referred to as

‘accusation’.

Child Any natural person below the age of 18years.

Defendant Any natural person subject to criminal proceedings initiated by the relevant authorities due

to suspicion or charge of having committed a crime. The term is also used in this report to

mean ‘suspect’, ‘accused person’ or ‘requested person’ (see separate definitions of these

terms in this glossary).

Deprivation of liberty Arrest or any type of confinement in a restricted space by the authorities, including when

the police apprehend and question a person without a judicial decision or a warrant. That

person may be set free after questioning; however, deprivation of liberty has taken place

if, for some period of time, the person was not allowed to leave police custody.

European Arrest Warrant

An arrest warrant based on Council Framework Decision 2002/584/JHA of 13June 2002 on

the European Arrest Warrant and the surrender procedures between Member States, valid

throughout all Member States of the EU. Once issued by one Member State (the ‘issuing

Member State’), it requires another Member State (the ‘executing Member State’) to arrest

a criminal suspect or sentenced person and transfer them to the issuing state so that the

person can be put on trial or complete a detention period.

Executing Member State The Member State responsible for the execution of a European Arrest Warrant.

Issuing Member State The Member State issuing a European Arrest Warrant for acts punishable by the law of that

Member State by a custodial sentence or a detention order.

Judge Any public official with the authority and responsibility to decide on criminal cases in a court

or make decisions on legal matters.

Judicial authority A judicial authority of a Member State that is independent and competent to issue or execute

European Arrest Warrants by virtue of the law of that state.

Law enforcement authority National police, customs or other authority that is authorised to detect, prevent and investigate

offences and to exercise authority and coercive force.

Lawyer Any person who is authorised to pursue professional legal activities, including to advise

people about the law and to represent them in court and other legal proceedings. More

specifically, in the context of this report, this includes defence lawyers, as persons authorised

to advise and represent defendants.

Legal aid System of funding accessible to people with insufficient or no means to cover professional

legal help and the costs of the proceedings themselves.

Pre-trial detention Deprivation of a defendant’s liberty imposed before the conclusion of a criminal case in the

context of judicial proceedings by a judicial authority (i.e. a judge, an investigative judge, a

court). Not to be confused with police detention, which takes place prior to bringing a

suspected person before a judge.

Prosecutor A public official, who, inter alia, institutes and conducts legal proceedings against a defendant in

respect of a criminal charge, representing the state.

Questioning Any oral interview or interrogation of a person by the police, a prosecutor or a judge during which

they are asked questions about their knowledge of or possible involvement in a criminal offence.

Requested person An individual who is the subject of an arrest warrant issued by any of the 27 Member States of the

EU. A European Arrest Warrant is issued to request the person’s arrest and extradition back to the

issuing state to serve a sentence or to face criminal charges.

Speciality rule The speciality rule entails that a requested person is generally surrendered in respect only of the

offences specified in the European Arrest Warrant, and it can therefore block prosecution or

punishment for offences not listed in the EAW.

Suspect Any natural person who has been thought of as having committed a criminal offence, even before

that person is made aware, by official notification or otherwise, that they are a suspect. The term

commonly refers to the initial stages of criminal investigations/ pre-trial proceedings.

Witness Any natural person who has been summoned to give testimony. Unlike a suspect, such a person

can be compelled to take an oath during the procedure to ensure that any statement made to the

judge is truthful. However, a witness can refuse to give a statement in evidence if there is a

possibility of self-incrimination.

Abbreviations

Charter Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union

CJEU Court of Justice of the European Union, formerly the European Court of Justice

EAW European Arrest Warrant

ECHR European Convention on Human Rights

ECtHR European Court of Human Rights

EU European Union

FRA European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights

ICCPR International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights

SIS Schengen information system

Country codes

Code EU Member State

AT Austria

BE Belgium

BG Bulgaria

CY Cyprus

CZ Czechia

DE Germany

DK Denmark

EE Estonia

EL Greece

ES Spain

FI Finland

FR France

HR Croatia

HU Hungary

IE Ireland

IT Italy

LT Lithuania

LU Luxembourg

LV Latvia

MT Malta

NL Netherlands

PL Poland

PT Portugal

RO Romania

SE Sweden

SI Slovenia

SK Slovakia

Key findings and FRA opinions

Building on previous research by the European Union Agency for Fundamental

Rights (FRA) on criminal procedural rights and cross-border cooperation in

criminal matters, undertaken at the specific request of the European

Commission, this report presents the findings of the most recent project

carried out by FRA on selected fundamental rights of persons subject to

European Arrest Warrant (EAW) proceedings. The report deals with

proportionality in the application of EAWs, fundamental rights-based grounds

for non-execution and the rights to access to a lawyer, to information and

to translation and interpretation during EAW proceedings.

The main objective of Council Framework Decision 2002/584/JHA of 13June

2002 on the European Arrest Warrant and the surrender procedures between

Member States (the EAW framework decision) is to address impunity and

to bring those who have fled the country in which their crime was committed

to justice. To achieve that, an issuing Member State issues an arrest warrant,

which must be swiftly executed by the executing Member State, without

examining the substance of the warrant, in the spirit of mutual trust and

mutual recognition. Requested persons have limited opportunities to challenge

the warrant; however, during the proceedings they have certain rights as

guaranteed by the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union

(the Charter) and secondary law instruments, such as the EAW framework

decision and the criminal procedural rights framework. Relevant international

human rights instruments, such as the European Convention on Human Rights

and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, also apply,

addressing in particular the prohibition of torture and inhuman or degrading

treatment in the event of extradition.

An EAW– like any measure leading to deprivation of liberty– should be

proportionate and narrowly tailored to its objective. The principle of

proportionality is one of the guiding principles of the EU legal order. It restricts

the authorities in exercising their powers by requiring them to strike a balance

between the means used and the expected aim to be achieved. An arrest

warrant, being a measure restricting an individual’s right to liberty and right

to respect for private and family life, should always be proportionate to the

aim it seeks to achieve.

Relying on principles of mutual trust and mutual recognition, the executing

authorities should in principle surrender the requested persons swiftly.

However, in recent years, the Court of Justice of the European Union has

confirmed that surrender should be postponed or even refused when respect

for certain fundamental rights, such as the right to dignity or to freedom

from inhuman or degrading treatment, is at stake. In short, whenever there

is a risk that a requested person will be subjected to inhuman or degrading

treatment upon surrender, the executing authority has a duty to assess this

risk and, if necessary, postpone or refuse surrender. The same principle also

applies to the risk of denial of justice.

Requested persons also have procedural rights during EAW proceedings. The

European legislator has recognised their right to legal assistance both in the

country issuing the EAW and in the country executing it. They have the right

to understand what is happening to them; therefore, they have the right to

information about their rights and the EAW procedure, including the

consequences of their decisions. They also have the right to interpretation

and translation during the proceedings.

This report examines how these principles and rights are upheld in practice,

based on desk research and interviews with professionals in 19 Member

States and requested persons in 6 Member States. The research does not

cover the full scope of the EAW framework decision and the criminal procedural

rights legal framework but focuses on specific rights of requested persons

as specified in the various sections of the report, including the right to

freedom from torture and inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment

and the right to access to a lawyer and information, interpretation and

translation during the proceedings. FRA’s evidence indicates that, while the

practical implementation of the rights of requested persons varies across

the Member States covered, some common challenges exist.

The research covers the 19 Member States that were not covered by FRA’s

previous published research on the EAW (which covered 8 Member States),

namely Belgium, Croatia, Cyprus, Czechia, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Hungary,

Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Portugal, Slovakia,

Slovenia, Spain and Sweden. The report draws on the experiences of between

5 and 15 interviewees per country (161 professionals and 21 requested persons

were interviewed in total). In light of this, the findings do not claim to be

representative of the situation in each Member State or the EU as a whole.

Nevertheless, they provide a unique comparative insight into the views of

the professionals involved and of people who have experienced at first hand

how EAW proceedings are conducted in practice. This helps us to understand

the fundamental rights challenges they have encountered and provides

evidence to enable a critical assessment of the practical implementation of

this legislative instrument 20years after its entry into force. The report also

provides– in the Introduction– examples of notable developments with

respect to the application of the EAW in those Member States that FRA

researched previously.

ASSESSING AND RESPECTING FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS

WHEN EXECUTING A EUROPEAN ARREST WARRANT

The EAW framework decision does not contain any

provision on non-execution on the basis of a breach

of the requested person’s fundamental rights in the

issuing Member State. However, Article1(3) of the

EAW framework decision, read together with recitals12

and 13, clarifies that fundamental rights and

fundamental legal principles should be respected when

implementing the EAW.

The jurisprudence of the Court of Justice of the European

Union confirms this. In cases in which the possibility

of violation of fundamental rights in the issuing state

was raised by the requested person or their

representatives, the court introduced a two-step test

to examine whether the execution of the EAW would

lead to a violation of a fundamental right such as the

prohibition of inhuman or degrading treatment, for

example in cases involving inhuman detention

conditions, or the right to a fair trial. In addition, the

court found that the executing authority must take a

serious health condition into consideration when

deciding on the surrender of an individual who is ill.

The research finds that judicial authorities in the

Member States covered do not always consider the

fundamental rights implications of surrendering

individuals when executing an EAW. For example,

interviewed lawyers pointed to examples of inhuman

and degrading detention conditions in the issuing state

and of disregard for the health and family situations

of requested persons. They referred to cases involving

the surrender of people who were seriously ill, despite

the fact that the particular situation of the individual

had been raised before the judicial authorities.

With regard to the risk of denial of justice owing to

violation of the right to a fair trial in the issuing state,

the research findings show that this is very rarely

examined.

Some interviewed judicial authorities consider that

the principles of mutual trust and mutual recognition

prevent them from examining the individual situations

of requested persons, detention conditions and access

to justice in the issuing Member State. They also argue

that these factors are to be considered only when

dealing with requests for extradition to non-EU

countries. In addition, some interviewed lawyers and

judicial authorities consider that all EU Member States

respect fundamental rights to the same extent and

that therefore there is no need to examine these

aspects.

FRA OPINION

Member States should ensure that

the fundamental rights implications

of cross-border transfers are duly

considered in individual cases, in line

with the evolving jurisprudence of

the Court of Justice of the European

Union and with their obligations under

EU and international law. Accordingly,

their national courts should properly

assess the real risk of fundamental

rights violations, in particular any

violation of the prohibition of inhuman

or degrading treatment in criminal

detention facilities, and take action

to prevent them. Executing judicial

authorities should also examine

the risk of denial of justice in the

issuing state if the issue is raised by

the requested person or their legal

representative.

Executing authorities are encouraged

to assess the impact of surrendering

an individual on their fundamental

rights with regard to individual

aspects such as their health when

there is a risk of a possible violation

of fundamental rights.

FRA reiterates its opinion, previously

presented in the report Criminal

Detention and Alternatives:

Fundamental rights aspects in EU

cross-border transfers, that it is

particularly important that individual

situations are strictly evaluated when

the issue of inhuman conditions of

detention is raised. This applies in

particular when there is objective

evidence of systemic shortcomings in

a Member State’s detention facilities.

ENSURING THAT LEGAL REPRESENTATION IN THE

EXECUTING STATE IS REAL AND EFFECTIVE

In accordance with Article11(2) of the EAW framework

decision, a requested person has the right to be

assisted by a legal counsel for the purpose of the

execution of the EAW. In line with Article47 of the

Charter, Article10 of Directive 2013/48/EU on the right

of access to a lawyer in criminal proceedings and in

European Arrest Warrant proceedings, and on the right

to have a third party informed upon deprivation of

liberty and to communicate with third persons and

with consular authorities while deprived of liberty,

reiterates and further elaborates on the requested

person’s right to a lawyer in the executing state.

Accordingly, requested persons have the right to access

to a lawyer in such time and in such a manner as to

allow the requested persons to exercise their rights

effectively and in any event without undue delay from

the moment of deprivation of liberty. In addition, a

requested person has the right to meet their lawyer

and communicate with them confidentially. Recital45

specifies that executing Member States should make

the necessary arrangements to ensure that requested

persons are in a position to exercise effectively their

right of access to a lawyer in the executing Member

State, including by arranging the assistance of a lawyer

when requested persons do not have one, unless they

have waived that right. Such arrangements, including

those on legal aid if applicable, should be governed

by national law. They could entail, inter alia, the

competent authorities arranging the assistance of a

lawyer on the basis of a list of available lawyers from

which requested persons could choose.

The research shows that the right to access to a lawyer

in the executing state is overall generally complied

with. Interviewees agree that in general requested

persons receive legal assistance from public defenders.

However, the research also shows that requested persons receive little to

no help from the authorities when hiring a private lawyer. Since requested

persons do not always have connections in the executing state, they may

face difficulties in finding a lawyer of their choice.

In addition, it appears from the interviews that, while in general a requested

person has the opportunity to meet their lawyer before the hearing,

consultations between a requested person and their lawyer are sometimes

rushed or held in a space that is not suitable, such as a courthouse corridor.

FRA OPINION

While Member States continue to fulfil

their obligations to provide a requested

person with access to a lawyer and

to secure a public defender for them

if necessary in the executing state,

they are encouraged also to develop

a mechanism, in collaboration with

bar associations, enabling requested

persons to hire their own lawyer if

they wish to do so. Lists of lawyers

with experience in EAWs, detailing

the languages that they speak, could

be provided to requested persons

to facilitate their hiring a lawyer of

their choice if they do not wish to

benefit from the assistance of a public

defender. Member States should

also ensure that sufficient time and

adequate facilities are available to

enable requested persons to consult

with their lawyers before the first

hearing. This could be achieved, for

example, by having dedicated rooms in

courthouses and making sure that the

relevant procedures allow sufficient

time.

ENSURING ACCESS TO LEGAL REPRESENTATION IN THE

ISSUING STATE

In accordance with Article10(4) of Directive 2013/48/

EU on the right of access to a lawyer in criminal

proceedings and in European Arrest Warrant

proceedings, a requested person has the right to access

to a lawyer in the issuing Member State (so-called dual

legal representation). This provision introduced an

additional safeguard to strengthen the procedural rights

of requested persons during EAW proceedings. The

competent authority in the executing Member State

must inform requested persons, without delay, that

they have the right to appoint a lawyer in the issuing

Member State. The lawyer in the issuing Member State

is to assist the lawyer in the executing Member State

by providing them with information and advice with a

view to the effective exercise of the rights of requested

persons under the EAW framework decision.

The research shows that, in practice, dual legal

representation is a rare occurrence. The authorities do

not systematically inform requested persons about this

right and do not provide any assistance with the

appointment of a lawyer in the issuing state. Only a

handful of Member States provide in the EAW form

that has to be completed by the issuing state authorities

and forwarded to the executing state the name of the

lawyer representing the requested person in the issuing

state or a list of lawyers potentially able to do so. Judicial

authorities interviewed for the research emphasised

that they do not feel competent to elaborate on the

right to legal representation in another jurisdiction;

therefore, when executing an EAW, they do not inform

the requested person about their right to a lawyer in

the issuing state. Interviewed lawyers highlighted that

legal representation in the issuing state very often

depends on the willingness of the lawyer representing

the requested person in the executing state to use their

professional and private contacts.

The research findings also show that the role of the

lawyer in the issuing state is not always understood

by judges, prosecutors and lawyers. Several

interviewees from all professional groups questioned

the need for dual legal representation and were unable

to see how this right could contribute to safeguarding

the right to a fair trial in EAW proceedings. In contrast,

other judges, prosecutors and lawyers, especially

those with experience as legal representatives in the issuing state, could

see the added value of dual legal representation in ensuring the overall

fairness of proceedings. Those interviewees highlighted instances in which

the assistance of a lawyer in the issuing state led to the withdrawal of an

EAW that had been issued erroneously (against the wrong person or in

connection with a trivial offence) or to negotiations with the issuing authorities

that secured certain outcomes, such as agreeing on a penalty before surrender,

which in turn led to voluntary surrender. However, the interviewees also

emphasised difficulties in communication between lawyers in two states,

mainly because of tight deadlines and differences between jurisdictions.

FRA OPINION

Member States should ensure

effective access to dual legal

representation in practice in line with

their obligations under Directive

2013/48/EU on the right of access to

a lawyer in criminal proceedings and in

European Arrest Warrant proceedings.

National authorities responsible for

the administration of justice should

develop guidance for police and judicial

authorities highlighting the need to

inform requested persons about this

right without delay. Judicial authorities

should verify at the first questioning

whether a requested person is indeed

aware of this right and whether they

want to exercise it.

Issuing Member States are encouraged

to follow the good practice of

including the name of the lawyer

representing the requested person

in the issuing state in the EAW form.

If a person does not have a lawyer

appointed to represent them in the

issuing state, Member States are

encouraged, in cooperation with bar

associations, to attach to the EAW form

a list of lawyers specialising in EAW

proceedings practising in the issuing

state, specifying the languages that

they speak.

Member States, in cooperation with

EU bodies, are encouraged to take

measures to improve cooperation

among lawyers and help them gain

a deeper understanding of the EAW.

PROVIDING INFORMATION TO REQUESTED PERSONS IN

AN EFFECTIVE AND RIGHTSCOMPLIANT WAY

FRA OPINION

Member States should consider

developing materials for police officers

responsible for arresting requested

persons in EAW proceedings. Such

materials could include a simple

checklist to facilitate the prompt

provision of information to requested

persons and emphasise the need to

orally explain crucial information. In

addition, national authorities could

consider developing materials to assist

police officers, judges and prosecutors

in providing information to requested

persons in a simple way. For example,

they could produce leaflets or other

explanatory materials that could be

translated into the most commonly

spoken languages.

National authorities are encouraged

to ensure that all documents provided

to requested persons are written in

simple and accessible language,

avoiding legal jargon as far as

possible. Member States could develop

additional materials and briefings for

police officers and legal professionals

on the various factors that can

compromise an individual’s ability

to understand the procedure and the

consequences of various decisions.

Member States are encouraged to

cooperate with the European Judicial

Training Network and national bar

associations to develop training

modules and materials, such as

checklists to help professionals dealing

with EAW proceedings to ensure that

requested persons are better informed.

In accordance with Article47 of the Charter and

Article11(1) of the EAW framework decision, the

executing competent judicial authority should inform

the requested person about the EAW and its content,

as well as the possibility of consenting to surrender

to the issuing judicial authority. According to Article5

of Directive 2012/13/EU on the right to information in

criminal proceedings, persons arrested under the EAW

should be provided promptly with an appropriate letter

of rights containing information about their rights. The

letter of rights must be drafted in simple and accessible

language. Furthermore, in accordance with Article6(2)

of Directive 2012/13/EU, all arrested persons should

be informed about the reasons for their arrest.

As a general principle of the right to information, all

information should be provided in simple and accessible

language, taking into account the particular needs of

a given person.

The research shows that, in general, requested persons

are informed about their rights, the reasons for their

arrest and the content of the EAW. Interviewed lawyers

nevertheless emphasise that, when an EAW is entered

into the Schengen information system , the information

about the reasons for arrest and the content of the

EAW is often delayed by several days. In general, with

respect to EAWs, interviewed lawyers suggest that

the information about rights is not always provided

promptly after a person’s arrest. They suggest that in

some Member States police officers do not explain

any rights orally but, instead, hand a letter of rights

to the requested person. There are also reported

instances of requested persons being provided with

a letter of rights applicable to general criminal

proceedings and not to EAW proceedings, without the

differences being explained to them. Judicial authorities

interviewed in a few Member States referred in this

context to manuals or checklists for officers dealing

with EAWs, which help them to inform requested

persons about their rights and specific aspects of EAW

proceedings.

Interviewed lawyers suggest that requested persons

do not always understand the information provided

to them by judicial authorities, in particular regarding

the possibility of consenting to surrender and its

consequences (e.g. that this means waiving the

principle of speciality, which could prevent them from being prosecuted for

offences not mentioned in the EAW framework decision). Therefore, in some

of the Member States covered, to facilitate provision of information and help

to ensure that requested persons fully understand the information provided,

the authorities have developed special checklists for police officers and

judicial authorities that include all the information that needs to be provided

to requested persons.

The research does indicate that requested persons do not fully understand

all the information provided. This seems to be a problem due to a myriad of

factors, such as the fast pace of proceedings, a person’s state of shock upon

arrest, individuals’ characteristics– such as the language that they speak or

their level of education– and the provision of documents containing lengthy

lists of rights, often written in complex legal language.

In the context of providing information to requested persons, interviewed

judges, prosecutors and lawyers highlighted that all professionals dealing

with EAWs would benefit from specialised training on EAW proceedings, as

they differ from criminal proceedings and many professionals lack experience

in them.

ENSURING ADEQUATE INTERPRETATION AND

TRANSLATION

FRA OPINION

Member States should ensure, in

every case where it is necessary, the

availability of qualified interpreters

and translators. If there is a lack of

suitable interpreters and translators,

Member States are encouraged to

cooperate with relevant national and

European professional associations of

legal translators and interpreters to

develop ways of sharing the pool of

available interpreters and translators

between Member States.

Moreover, to ensure that

interpretation and translation are

of an adequate standard, Member

States are encouraged to introduce

mechanisms for verifying interpreters’

and translators’ actual ability to

understand, interpret and translate

legal terms and concepts. FRA

reiterates its opinion, previously

presented in the report Rights of

suspected and accused persons across

the EU: Translation, interpretation

and information, that Member States

should consider introducing relevant

safeguards to maximise the quality of

translation and interpretation.

Under Article47 of the Charter and Article11(2) of the

EAW framework decision, a requested person has the

right to be assisted by a legal counsel and by an

interpreter in accordance with the national law of the

executing Member State. Moreover, Directive 2010/64/

EU on the right to interpretation and translation in

criminal proceedings sets forth additional legal

provisions on a requested person’s right to access

translation and interpretation services during EAW

proceedings.

In accordance with Article2(7) of Directive 2010/64/

EU, executing Member States should ensure that the

relevant authorities provide requested persons who

do not speak or understand the language of the

proceedings with interpretation without delay during

criminal proceedings before investigative and judicial

authorities, including during police questioning, all

court hearings and any necessary interim hearings.

Under Article 3(6) of Directive 2010/64/EU, in

proceedings for the execution of an EAW, the executing

Member State must ensure that its competent

authorities provide any person subject to such

proceedings who does not understand the language

in which the EAW is drawn up, or into which it has

been translated by the issuing Member State, with a

written translation of that document. An oral translation

or oral summary of the EAW may be provided instead

of a written translation on condition that such oral

translation or oral summary does not prejudice the

fairness of the proceedings.

The research shows that, in general, requested persons

are provided with interpretation services and

translations during EAW proceedings.

However, the quality of interpretation services received

much criticism, with most interviewees from all groups noting that it was

poor. Interviewees, for example, stated that anyone who spoke the language

could be hired as an interpreter, without their necessarily having any relevant

training or experience. The findings also highlight challenges encountered

in providing interpretation services for non-EU languages or less widely

spoken EU languages. In such cases, it seems that identifying and quickly

hiring interpreters is not always possible.

When it comes to the translation of the EAW, the findings show that providing

requested persons with an orally summarised translation of the document

is very common and often done instead of providing a full written translation.

Interviewees attribute this to the fast pace and short deadlines of the

proceedings, which leave insufficient time to employ translators.

Introduction

WHY THIS REPORT?

Council Framework Decision 2002/584/JHA of 13June 2002 on the European

Arrest Warrant and the surrender procedures between Member States (the

EAW framework decision) reflects the principle of mutual recognition in

criminal matters(

1

). Based on the principle of mutual recognition, the European

Arrest Warrant (EAW) allows a judicial decision issued in one EU Member

State– with a view to the arrest and surrender for the purposes of conducting

a criminal prosecution or executing a custodial sentence or detention order–

to be carried out in another Member State(

2

).

The year 2022 saw the 20th anniversary of the adoption of the EAW framework

decision. To mark that occasion, the Council invited the European Union

Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA) to consider continuing its research on

the right to access a lawyer and other procedural rights in criminal and EAW

proceedings. It suggested extending the research to cover the Member States

that had not been covered previously(

3

) and placing a special emphasis on

the experiences of lawyers involved in surrender proceedings(

4

). This research

responds to that call. The opinions deriving from the research seek to

contribute to the better implementation of the current framework at the EU

and national levels.

This report is addressed primarily to the EU institutions and Member State

authorities, including their national police and criminal justice authorities. It

sets out to assist the European Commission in assessing the practical

application of the rights and safeguards enshrined in the EAW framework

decision and relevant procedural rights directives. The report also seeks to

produce evidence that can assist Member States in their efforts to enhance

their legal and institutional responses in EAW proceedings and proceedings

involving other cross-border judicial instruments. For more details regarding

particular Member States covered in this report, please see the relevant

country studies prepared by FRA’s multidisciplinary research network,

Franet(

5

).

Mutual

recognition

and mutual

trust

Mutual recognition and mutual trust are the cornerstone principles of European cooperation

in criminal matters. This means that EU Member States are bound to recognise and enforce

judicial decisions delivered in other Member States. Although legal systems may differ, the

decisions reached by judicial authorities across the EU should be accepted as equally valid.

Mutual recognition strengthens cooperation between Member States, accelerates proceedings,

has the potential to enhance the protection of individual rights and, all in all, strengthens

legal certainty across the EU by ensuring that a ruling delivered in one Member State is not

challenged in another. This is justified by the requirement that all Member States must meet

the standards of human rights protection set out in the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the

European Union (the Charter).

SCOPE AND PURPOSE

The main objective of the research is to examine how national authorities

apply selected procedural rights and safeguards guaranteed by EU law in

EAW proceedings, with a special emphasis on the experiences of lawyers

involved in surrender proceedings. The Council reiterated the need to respect

the right to a fair trial in surrender proceedings and considered it useful for

FRA to continue to research respect for procedural rights in surrender

proceedings. Responding to the Council conclusions of 23November 2020,

this report will serve as a valuable contribution to the proper implementation

and execution of the EAW framework decision and the body of law adopted

as part of the roadmap for strengthening procedural rights in criminal

procedures, taking into due account fundamental rights safeguards and

standards.

FRA ACTIVITY

This report is the latest in a series published by FRA on criminal justice procedural rights, which to date includes the following.

― Underpinning Victims’ Rights– Support services, reporting and protection (2023).

― Children as suspects or accused persons in criminal proceedings– Procedural safeguards (2022).

― Presumption of Innocence and Related Rights– Professional perspectives (2021).

― Rights in Practice: Access to a lawyer and procedural rights in criminal and European Arrest Warrant proceedings (2019).

― Victims’ Rights as Standards of Criminal Justice (2019). This is PartI of a series of four reports entitled Justice for Victims of

Violent Crime; it outlines the development of victims’ rights in Europe and sets out the applicable human rights standards.

― Proceedings That Do Justice (2019). PartII of the series Justice for Victims of Violent Crime focuses on procedural justice

and on whether or not criminal proceedings are effective, including in terms of giving a voice to victims of violent crime.

― Sanctions That Do Justice (2019). PartIII of the series Justice for Victims of Violent Crime focuses on sanctions and

scrutinises whether or not the outcomes of proceedings deliver on the promise of justice for victims of violent crime.

― Women as Victims of Partner Violence (2019). PartIV of the series Justice for Victims of Violent Crime focuses on the

experiences of one particular group of victims, namely women who have endured partner violence.

― Children deprived of parental care found in an EU Member State other than their own– A guide to enhance child

protection focusing on victims of trafficking (2019). This guide sets out the relevant legal framework that governs the

protection of children who are deprived of parental care and/or are found in need of protection in an EU Member State

other than their own, including child victims of trafficking, and their treatment in criminal proceedings.

― Children’s Rights and Justice– Minimum age requirements in the EU (2018). This report outlines Member States’

approaches to age requirements and limits regarding child participation in judicial proceedings, procedural safeguards and

the rights of children involved in criminal proceedings, as well as issues related to depriving children of their liberty.

― Child-friendly Justice– Perspectives and experiences of children involved in judicial proceedings as victims, witnesses or

parties in nine EU Member States (2017). This report is based on interviews with justice professionals and police and with

several hundred children involved as victims, witnesses or parties in criminal and civil judicial proceedings to learn about

their treatment, with a focus on cases involving sexual abuse, domestic violence, neglect and severe custody conflicts.

― Criminal Detention and Alternatives: Fundamental rights aspects in EU cross-border transfers (2016). This report provides

an overview of Member States’ legal regulations in respect of framework decisions on transferring prison sentences,

probation measures and alternative sanctions, as well as pre-trial supervision measures, to other Member States.

― Rights of suspected and accused persons across the EU: Translation, interpretation and information (2016). This report

reviews Member States’ legal frameworks, policies and practices regarding the rights to information, translation and

interpretation in criminal proceedings.

— Handbook on European law relating to access to justice (2016). This publication summarises the key European legal

principles in the area of access to justice, focusing on civil and criminal law.

The report builds on previous FRA research on procedural rights published

between 2016 and 2022. Importantly, the current report adds value in that it

includes the results of research on those Member States that were not covered

in the 2019 report on right to access to a lawyer in criminal and EAW proceedings.

The report focuses on rights and safeguards introduced by the jurisprudence

of the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU), the EAW framework

decision and the criminal procedural rights directives outlining the rights to

interpretation and translation(

6

), to information(

7

), to access to a lawyer(

8

)

and to legal aid(

9

). The report aims to highlight new findings and to avoid

repeating those from the previous research or duplicating other existing

research, although at times it refers back to issues discussed in previous work.

As requested by the Council in its conclusions(

10

), the report covers 19 EU

Member States (Belgium, Croatia, Cyprus, Czechia, Estonia, Finland, Germany,

Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Portugal, Slovakia,

Slovenia, Spain and Sweden). However, at times there are references to other

Member States not covered by the research (e.g. Austria and France) or

non-EU countries (e.g. Türkiye and the United Kingdom). The EAW framework

decision is applied in the entire EU in respect of any person being sought by

the justice authorities, not only EU citizens, and therefore some cases referred

to are connected to non-EU countries and their citizens. The United Kingdom

applied the EAW framework decision until 31December 2020; therefore, the

experiences of requested persons from that country are included in the

analysis.

The eight countries covered in the 2019 report are not included in this

research(

11

). However, it should be noted that there have been developments

in the Member States covered in the 2019 report since its publication. This

is true in particular of the Netherlands and Poland, where a dialogue between

the Rechtbank Amsterdam (the District Court of Amsterdam) and the Polish

courts on the question of the application of the rule of law in the execution

of an EAW has taken place following the numerous preliminary ruling questions

sent by the Dutch and German courts to the CJEU(

12

).

How to

interpret

the research

findings

The findings are based on information provided during interviews with professionals (defence

lawyers, judges and prosecutors), as well as interviews with persons who were requested by a

Member State for surrender under the EAW (‘requested persons’) and their representatives. In

light of the qualitative nature of this research and the limited number of interviews conducted

in each Member State covered (see Table1), with 182 interviews in total, the findings cannot be

considered representative, nor can they be generalised with respect to other Member States.

Nevertheless, they serve to illuminate some challenges and highlight promising practices in the

implementation of the EAW framework decision and the criminal procedural legal framework.

The report provides policymakers and professionals with examples of initiatives in different

Member States that variously address a number of common challenges identified in the

research, elements of which could be adapted for use in their own national contexts.

STRUCTURE OF THE REPORT

The report is divided into four thematic chapters. Each chapter considers– in

law and in practice– a different aspect of EAW proceedings and the

corresponding procedural rights of requested persons at stake. Chapter1

outlines the fundamental rights implications of issuing and executing EAWs,

in particular the proportionality aspects of issuing an EAW and the risks of

possible human rights violations– mainly violations of the prohibition of

torture and inhuman or degrading treatment and the right to a fair trial– upon

surrender to the executing Member State. Chapter2 examines the right to

access to a lawyer in EAW proceedings and the role it plays in ensuring

respect for other procedural rights. Chapter3 addresses the right to information

in EAW proceedings. Chapter4 considers the right to interpretation and

translation. The report ends with a conclusion summarising the main findings.

METHODOLOGY AND CHALLENGES

The research aimed to gain insights into the implementation and practical

application of selected fundamental rights of requested persons as enshrined

in the EAW framework decision.

It involved desk research and fieldwork (interviews), as well as an experts’

meeting organised by FRA in October 2022. The research covers the 19

Member States (Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Czechia, Estonia, Germany,

Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Portugal, Slovakia,

Slovenia, Spain and Sweden) that were not covered in FRA’s previous report

Rights in Practice: Access to a lawyer and procedural rights in criminal and

EAW proceedings.

Desk research

The desk research was conducted by Franet

.

It involved an in-depth review

of the legal framework and provisions in place in each Member State regarding

selected fundamental rights of requested persons (right to access to a lawyer,

right to information and right to interpretation and translation) as enshrined

in the EAW framework decision, as well as legal provisions governing the

issuing and execution of an EAW. The research covered legislative acts, case-

law, explanatory reports, parliamentary discussions, guidelines, policy

documents– where necessary to understand the legal context– academic

articles and similar resources.

Fieldwork (interviews)

The fieldwork was also conducted by Franet. To ensure that the information

and data gathered were recent, interviews covered arrests carried out between

27November 2016 and 31December 2021 (31December 2022 in the case of

Sweden , as the Swedish researchers were contracted at a later date). The

requested persons interviewed included requested persons who had been

subject to EAW proceedings in the Member State where the interview took

place (at least two out of the five interviews conducted in each country) or

in any other EU Member State.

A total of 182 respondents were interviewed. These interviewees from the

19 selected Member States were made up of 75 lawyers, 77 judges or

prosecutors, 21 requested persons and 9 lawyers speaking on behalf of

requested persons (Table1).

TABLE: NUMBERS OF INTERVIEWEES BY MEMBER STATE AND TARGET

GROUP

Member

State

Lawyers

Judges/

prosecutors

Requested

persons

Lawyers speaking

on behalf of

requested

persons

Total

number of

interviewees

BE 4 4 — — 8

CY 3 3 3 2 11

CZ 5 4 — — 9

DE 5 5 — — 10

EE 3 3 — — 6

ES 5 5 3 2 15

FI 4 4 5 — 13

HR 4 5 — — 9

HU 4 4 — — 8

IE 4 4 — — 8

IT 5 5 5 — 15

LT 4 4 — 5 13

LU 3 3 — — 6

LV 4 4 — — 8

MT 4 3 — — 7

PT 4 5 5 — 14

SI 4 4 — — 8

SK 4 5 — — 9

SE 2 3 — — 5

Total 75 77 21 9 182

Source: FRA, 2022

The first stage of the project– covering the interviews with lawyers, judges

and prosecutors– was carried out between April 2022 and March 2023.

Requested persons (and their representatives) were interviewed during the

second stage, between February 2023 and April 2023. Due to resource

constraints, interviews with persons requested for surrender through EAWs

were conducted in only six Member States (Cyprus, Finland, Italy, Lithuania,

Portugal and Spain), and the interviews focused on their experiences of and

opinions about whether and how their fundamental rights were respected

in the EAW proceedings against them. It should be noted that lawyers

interviewed on behalf of requested persons during the second stage of the

fieldwork were asked to reflect on the specific experiences of their clients

and not on general practice in their Member States.

All interviewees– lawyers, judges, prosecutors and requested persons, or

their representatives when they were interviewed on their behalf– responded

to a questionnaire in a structured qualitative interview that covered their

experiences of and opinions on how selected fundamental rights of requested

persons had been respected and upheld during EAW proceedings and how

this had been achieved.

As noted, requested persons and their representatives were interviewed in

only 6 Member States of the 19 covered by this research. These Member

States were selected taking into account budgetary and human resource

constraints and the availability of requested persons. Securing interviews

with the requested persons was the most challenging aspect of the research,

as they were either very difficult to identify or not available for interview.

Therefore, as mentioned above, in some cases their representatives were

interviewed on their behalf.

The interviewers did not share the questionnaire with respondents in advance,

except for judges and prosecutors in Hungary; this was a formal requirement

for interviews with Hungarian judicial authorities. The interviewers encouraged

respondents to speak freely and draw on their personal experiences. Most

interviews were audio- or video-recorded, and all were documented using

a reporting template.

Experts’ meeting

The experts’ meeting took place at FRA’s premises in October 2022. FRA

invited 14 experts with experience of EAW proceedings: defence lawyers,

prosecutors, judges and representatives of Eurojust and the European Judicial

Network. The experts shared their experiences of and views on issuing and

executing EAWs and the procedural rights of requested persons.

Consultations

Given that, in its conclusions, the Council requested that FRA focus on lawyers’

experiences, FRA consulted professionals associated with the Council of Bars

and Law Societies of Europe when developing the research design and

methodology(

13

).

Endnotes

(

1

) S. Alegre and M. Leaf, ‘Mutual recognition in European judicial cooperation: A step too far too soon?’, European Law Journal, Vol.10, No2,

pp.200–217, 2004.

(

2

) Council Framework Decision 2002/584/JHA of 13June 2002 on the European Arrest Warrant and the surrender procedures between

Member States.

(

3

) FRA’s previous research had been published in FRA, Rights in Practice: Access to a lawyer and procedural rights in criminal and European

Arrest Warrant proceedings, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2019.

(

4

) Council conclusions ‘The European Arrest Warrant and extradition procedures– Current challenges and the way forward’, Brussels, 23

November 2020, para.29.

(

5

) For more information, see FRA’s webpage on Franet.

(

6

) Directive 2010/64/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20October 2010 on the right to interpretation and translation in

criminal proceedings (OJ L280, 26.10.2010, p.1).

(

7

) Directive 2012/13/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22May 2012 on the right to information in criminal proceedings (OJ

L142, 1.6.2012, p.1).

(

8

) Directive 2013/48/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22October 2013 on the right of access to a lawyer in criminal

proceedings and in European Arrest Warrant proceedings, and on the right to have a third party informed upon deprivation of liberty and

to communicate with third persons and with consular authorities while deprived of liberty (OJ L294, 6.11.2013, p.1).

(

9

) Directive (EU) 2016/1919 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26October 2016 on legal aid for suspects and accused persons

in criminal proceedings and for requested persons in European Arrest Warrant proceedings (OJ L297, 4.11.2016, p.1).

(

10

) Council conclusions ‘The European Arrest Warrant and extradition procedures– Current challenges and the way forward’, Brussels,

23November 2020, para.29.

(

11

) Having previously undertaken research on the EAW in eight Member States, and given the agency’s available budget, FRA was not in a

position to extend the research to cover all the remaining Member States and– at the same time– to undertake research again in those

eight Member States already covered by the previous EAW study.

(

12

) See, for instance, two preliminary rulings requested by the Netherlands: CJEU, joined cases C-354/20PPU and C-412/20PPU, L and P,

17December 2020, in which the CJEU confirms that a case-by-case examination of the risk of fundamental rights violations affecting

the requested person is necessary (see also the related news post); and CJEU, joined cases C-562/22 PPU and C-563/21 PPU, X and Y

v Openbaar Ministerie, 22February 2022, in which the CJEU clarifies its case-law on refusal to execute an EAW on fundamental rights

grounds (see also the related press release). See also P. Bard, Rule of Law– Sustainability and mutual trust in a transforming Europe,

Eleven International Publishing, The Hague, 2023, p.55 et seq.

(

13

) See the council’s website for more information.

21

ISSUING AND EXECUTING A

EUROPEAN ARREST WARRANT

FOCUSING ON PROPORTIONALITY

AND FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTSBASED

GROUNDS FOR NONEXECUTION

This chapter examines selected fundamental rights implications of issuing

and executing EAWs. It does not deal in detail with all the applicable rules

and principles– for instance, questions of double criminality or ne bis in

idem– as these have been discussed elsewhere(

1

).

The aim of the chapter is to examine whether specific fundamental rights

are properly considered by Member States when issuing and executing an

EAW. Therefore, it focuses mainly on the proportionality of the measure,

consideration of the individual situations of requested persons, detention

conditions and the right to a fair trial.

The chapter does not deal with grounds for non-execution of an EAW explicitly

listed in the EAW framework decision(

2

), but, rather, focuses on the

jurisprudence of the CJEU.

A. LEGAL OVERVIEW

Issuing a European Arrest Warrant

The EAW is issued by a judicial authority (an independent authority such as

a court or an independent prosecutor)(

3

) in one Member State (the issuing

Member State) to a judicial authority in another Member State (the executing

Member State), or– when the location of the requested individual is unknown–

it is entered into the Schengen information system (SIS) as an alert directed

to all Member States, for the purpose of criminal prosecution or the execution

of a custodial sentence(

4

). In either case, the executing Member State can

make surrender conditional on the crime being punishable under its law

(known as the double criminality requirement)(

5

). An EAW may not, however,

be subject to this requirement if the offence is included in the list of 32

offences set out in the EAW framework decision(

6

). The EAW framework

decision abolished the political offence exemption. Therefore, an EAW may

be issued for a political offence, although this is rare and very much debated(

7

).

The EAW framework decision does not refer to the application of the principle

of proportionality when issuing an arrest warrant. However, as the EAW must

always be based on a national arrest warrant, the principle of proportionality,

applicable to national warrants, extends to EAWs(

8

).

22

According to the CJEU, the issuing of an EAW rests on a two-level system of

protection of fundamental rights: at the level of issuing the national arrest

warrant and at the level of issuing the EAW(

9

). Both these tasks should be

entrusted to a ‘judicial authority’(

10

).

According to the CJEU, Article47 of the Charter requires that an EAW against

a person charged with a crime, or the national arrest warrant on which it is

based, be subject to review by a court in the issuing Member State(

11

). This is

not required when the warrant is based on a final conviction passed by a

court(

12

). The review should ensure that the fundamental rights, such as legal

and factual bases for deprivation of liberty, of the person whose arrest is

requested are respected(

13

). It can take place before or at the time of the

issuing of the EAW, but also thereafter at any time before the surrender of the

requested person(

14

). During this review, all available evidence, as well as the

conditions for and proportionality of issuing the EAW, should be examined(

15

).

CJEU case-law has not yet established clear criteria for proportionality when

issuing an EAW. What is certain is that the issuing judicial authority should

assess the proportionality of an EAW and this should be subject to effective

judicial review(

16

). This approach is also recommended in the General Secretariat

of the Council’s Final report on the 9th round of mutual evaluations on mutual

recognition legal instruments in the field of deprivation or restriction of liberty,

delivered to the Council delegations in March 2023(

17

). The executing authority

cannot refuse to execute an EAW based on proportionality concerns(

18

).

23

In its handbook on the EAW(

19

), the European Commission stresses that any

EAW should be proportionate to its aim and justified in each particular case

based on its circumstances(

20

). Accordingly, it proposes a list of factors that

judicial authorities should assess when considering whether to issue an EAW,

namely (a) the seriousness of the offence, (b) the severity of the penalty

likely to be imposed, (c) the likelihood of detention of the requested person

in the issuing Member State after surrender and (d) the interests of the

victims of the offence(

21

). The handbook also encourages issuing judicial

authorities to consider whether another judicial cooperation measure that

is less restrictive could be used instead of an EAW, by giving examples of

such measures(

22

). For instance, a suspect located in another Member State

could be examined via video link or by the authorities of that state, and if

considered necessary those authorities could execute a non-custodial

supervision measure against the suspect. The relevant instruments discussed

in the handbook are the European Investigation Order(

23

), transfer of

prisoners(

24

), the European Supervision Order(

25

), transfer of probation

decisions and alternative sanctions(

26

), mutual recognition of financial

penalties(

27

) and transfer of criminal proceedings(

28

).

National laws

National laws govern the procedures for issuing an EAW and rule on whether

or not the national (judicial) authorities have the capacity to issue such

warrants(

29

). Most Member States covered by this research permit the issuing

of warrants for the purpose of prosecution of a criminal offence punishable

with a maximum sentence of imprisonment of at least 12months or execution

of a custodial sentence if the term of imprisonment imposed or the remainder

of it is at least 4months (Croatia(

30

), Cyprus(

31

), Czechia(

32

), Estonia(

33

),

Finland(

34

), Hungary(

35

), Ireland(

36

), Latvia(

37

), Lithuania(

38

), Malta(

39

),

Portugal(

40

), Slovakia(

41

), Slovenia(

42

), Spain(

43

) and Sweden(

44

). Luxembourg

has slightly different conditions. For example, to issue a warrant for the

purpose of prosecuting a criminal offence, the offence must be punishable

by at least 2years of imprisonment, with certain exceptions(

45

). In addition,

in Belgium, to avoid problems in practice with EAWs issued for trivial offences,

for the purpose of executing a sentence no EAW is to be issued if the sentence

remaining to be served is less than 2years(

46

). Certain exceptions exist, for

example if the nature of the crime is very grave, such as a crime against a

child, a sexual offence or a terrorist offence(

47

) .

The national laws of some Member States explicitly refer to the principle of

proportionality as a guiding principle for national judicial authorities, which

should ensure that EAWs are proportionate to their objectives (Belgium(

48

),

Croatia(

49

), Czechia(

50

), Hungary(

51

), Latvia(

52

), Lithuania(

53

), Slovakia(

54

)

and Sweden(

55

). Other Member States derive the obligation to have recourse

to the principle of proportionality from their constitutional orders (Germany(

56

),

Portugal(

57

), Slovenia(

58

) and Spain(

59

). Some laws also refer to other

conditions that in practice serve to ensure that the proportionality of the

measure is assessed, for example:

― ‘serious indications of guilt’ (Belgium(

60

) and Luxembourg(

61

);

―

grounds for suspecting that the requested person will not arrive voluntarily

for the consideration of the charges, based on the personal circumstances

of the requested person, the number and nature of the offences on which

the request for extradition is based or other relevant circumstances

(Finland(

62

);

―

reasonable grounds for believing believe that a person has either (a)

committed an extraditable offence or (b) unlawfully fled the country

after being convicted of an extraditable offence (Malta(

63

).

24

National

case-law on

the principle of

proportionality

Spain

The Constitutional Court has established that proportionality should be considered when

adopting any measure restricting fundamental rights. The court has ruled that ‘the

constitutionality of any measure restricting fundamental rights is determined by strict

observance of the principle of proportionality’. The court has provided guidance on how to

apply it; accordingly, the national authorities must consider:

― whether the measure is likely to achieve the proposed objective (assessment of suitability);

― whether, in addition, it is necessary, in the sense that there is no other more moderate

measure that could achieve the intended purpose with equal effectiveness (assessment of

necessity);

― whether, finally, it is weighted or balanced, in that it is likely to create more benefits or

advantages in the general interest than harm to other goods or values in conflict with it

(proportionality assessment in the strict sense).

Although not an EAW-specific ruling, the above proportionality criteria make it possible to

determine whether the issuance of an EAW is justified on a case-by-case basis, given the

consequences that its execution has for the fundamental rights of the defendant.

Source: Judgment of the Constitutional Court of 3March 2016 in Case 39/2016 (Sentencia 39/2016, de 3 de

marzo), Official State Gazette, No85, 8April 2016.

Portugal

The Porto Court of Appeal has explained that, since the execution of an EAW constitutes a

major restriction on a fundamental right, namely the right to liberty, and bearing in mind the

length of time that detention might last without a final decision being taken, the decision to

issue an EAW has to comply with, among other things, the principle of proportionality. This

means that the EAW must comply with three subprinciples.

― Adequacy. Is this measure the most appropriate for the case?

― Necessity. Is this measure that which will create the smallest burden?

― Proportionality in the strict sense. Is the measure the fairest available?

Source: Decision of the Porto Court of Appeal in Case 612/08.4GBOBR-A.P1 (Acórdão do Tribunal da Relação

do Porto– Processo 612/08.4GBOBR-A.P1), 18March 2015.

Laws in the vast majority of Member States covered do not allow for the

possibility of a requested person or their lawyer challenging the issuance of

an EAW. Only in Croatia(

64

), Slovakia(

65

) and Spain(

66

) do laws provide for

legal avenues to challenge the issuance of an EAW.

Executing a European Arrest Warrant

When a person is arrested based on an EAW, the authorities of the arresting

Member States decide whether to execute the warrant by surrendering the

requested person to the authorities of the issuing Member State. First, the

executing authorities should examine whether the conditions and requirements

for issuing the EAW have been complied with (e.g. whether it has been issued

for one of the offences for which it can be used, whether it has been issued

by a judicial authority subject to judicial review). If not, the executing

authorities should refuse to execute it(

67

). The CJEU has further clarified that

an EAW should be executed only by a ‘judicial authority’; what constitutes

such an authority is determined based on the same criteria used for issuing

authorities(

68

). Moreover, for the detention of a requested person to be

lawful, the deprivation of their liberty must follow a procedure prescribed

by law, as required by Article5(1) of the European Convention on Human

Rights (ECHR) and reflected in Article6 of the Charter. The European Court

of Human Rights (ECtHR) has pointed out that Member States’ judicial

authorities must comply with substantive and procedural national law for

detention to be lawful under Article5(1)(f) of the ECHR, which specifies the

25

arrest or detention of a person with a view to extraditing the individual as

a lawful ground for deprivation of liberty(

69

).

A person arrested based on an EAW may consent to be surrendered after

being properly informed about this possibility and having had the opportunity

to exercise their right to access a lawyer(

70

). If it is done ‘voluntarily’ and

while the requested person is ‘fully aware of its consequences’, the requested

person may also waive the application of the speciality rule before the

executing judicial authority(

71

).

Consent to

surrender and

the speciality

rule

The speciality rule entails that a requested person is generally surrendered in respect only

of the offences specified in the EAW, and it can therefore block prosecution or punishment

for other offences not listed in the EAW(*). The requested person may, however, waive the

application of the speciality rule. This may take place either automatically when they consent

to their surrender or separately. The waiver of the speciality rule follows automatically from

consent to surrender where the executing Member State has notified the General Secretariat

of the Council that it will, in its relations with other Member States that have given the same

notification, apply a presumption of speciality rule waiver. This applies unless in a particular

case the executing judicial authority states otherwise in its decision to surrender(**). Where

no such notification has been made, the speciality rule must be renounced separately. The

executing Member State should, in accordance with Article13(2) of the EAW framework

decision, ensure that any consent to surrender and, where this is a separate legal act, any

renunciation of the speciality rule are voluntary and have been expressed in full awareness of

the consequences. The requested person must therefore be fully informed about the meaning

and consequences of consent and waiver(***). The requested person’s consent and waiver of

the speciality rule must also be formally recorded.

(*) Council Framework Decision 2002/584/JHA, Article27(2). See, however, the applicable exceptions

set out in Article27(3).

(**) Council Framework Decision 2002/584/JHA, Articles13 and 27(1).

(***) Council Framework Decision 2002/584/JHA, Article27(3)(f).

In principle, consent to surrender may not be revoked, but Member States

are allowed to have different laws on that issue(

72

). If the requested person

consents to their surrender, the proceedings should be concluded within

10days with the person’s surrender to the issuing state(

73

). In certain cases,

giving consent may mean that the requested person automatically renounces

the application of the speciality rule; that is, the requested person could also

be prosecuted in connection with offences not mentioned in the EAW. This