Occasional Paper Series

The use of the Eurosystem’s

monetary policy instruments and its

monetary policy implementation

framework in 2020 and 2021

Marco Corsi, Yvo Mudde (editors)

No 304 / September 2022

Disclaimer: This paper should not be reported as representing the views of the European Central Bank (ECB).

The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the ECB.

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 304 / September 2022

1

Contents

Abstract 3

Non-technical summary 4

1 Introduction to the Eurosystem’s monetary policy instruments in

2020 and 2021 5

1.1 Overview of monetary policy instruments 6

2 Steering of short-term interest rates 8

2.1 Main developments in excess liquidity and money markets 8

Box 1 The interaction between developments in money markets and

money market funds and the ECB’s response during the COVID-

19 crisis 9

3 Minimum reserve requirements and the two-tier system 13

4 Credit operations 15

4.1 TLTROs 16

4.2 PELTROs, LTROs, MROs and the MLF 19

4.3 US dollar credit operations 20

4.4 The Eurosystem repo facility for central banks (EUREP) and

other repo agreements and foreign exchange swaps with foreign

central banks 22

5 Counterparty framework 24

5.1 Eligibility criteria and discretionary measures 24

5.2 Counterparties’ developments 25

6 Collateral framework 27

6.1 Changes to the collateral framework 27

6.2 Eligibility and mobilisation of collateral 30

Box 2 Acceptance of loans guaranteed by public guarantee schemes

within the ACC framework 32

7 Asset purchase programmes 34

7.1 Pandemic emergency purchase programme 34

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 304 / September 2022

2

7.2 Asset purchase programme 36

7.3 Securities lending programmes 40

Box 3 The role of the PEPP in the stabilisation and reduction of

volatility in the European government bond market 40

Box 4 The NGEU programme and its implications for monetary policy

implementation 43

8 Impact of the Eurosystem monetary policy implementation on its

balance sheet and liquidity conditions 46

8.1 Impact of Eurosystem monetary policy implementation on its

balance sheet 46

8.2 Excess liquidity and its distribution 48

8.3 Developments in autonomous factors 50

References 53

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 304 / September 2022

3

Abstract

The Eurosystem implements its monetary policy through a set of monetary policy

instruments (MPIs) that are either part of the standard toolbox or are developed to

deal with major economic and financial events with a potential adverse impact on

price stability and/or the transmission of monetary policy. In the review period

covered by this report (2020-2021), monetary policy action was dominated by the

Eurosystem’s response to the negative economic effects of the outbreak of the

COVID-19 pandemic. Through its action, the Eurosystem continued to expand its

balance sheet, in particular by scaling up its outright asset purchases and easing the

conditions of its targeted longer-term refinancing operations (TLTROs),

complemented by temporary changes in the collateral framework. The

accommodative monetary policy stance was preserved by maintaining the key ECB

interest rates at record-low levels, reinforced by the ECB’s forward guidance on

policy rates. This report provides a full overview of the Eurosystem’s monetary policy

implementation over the years 2020 and 2021.

JEL: D02, E43, E58, E65, G01

Keywords: monetary policy implementation, central bank counterparty framework,

central bank collateral framework, central bank liquidity management, non-standard

monetary policy measures

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 304 / September 2022

4

Non-technical summary

This paper provides a comprehensive overview of the use of the Eurosystem’s MPIs

over the period 2020 to 2021 and continues the series on this topic started in 2012.

1

The report is structured along three main themes, aimed at guiding the reader

through the various MPIs that were introduced or enhanced in the review period.

First, short-term interest rates were kept at very low levels – mostly close to but

below the interest rate on the deposit facility (DFR) – in an environment of very high

excess liquidity, thereby preserving a very accommodative monetary policy stance.

In addition, while minimum reserve requirements have continued to play a less

relevant role than in the past in steering short-term rates due to the large excess

liquidity, they served as reference for the two-tier system introduced in October

2019. This last instrument continued mitigating the side effects of the negative

interest rate policy on the transmission of monetary policy by exempting part of

banks’ excess reserves from negative remuneration. Sections 2 and 3 cover these

developments.

Second, liquidity provided by the Eurosystem through its credit operations more than

tripled in the review period (up to €2,207 billion), in particular as a result of the

attractive conditions under its TLTRO III operations, which ensured favourable bank

lending conditions during the pandemic. In parallel, a temporary expansion of the

collateral framework concomitant with a temporary higher risk tolerance, increased

collateral availability thereby facilitating broad-based participation in these

operations. As part of the swift ECB reaction to the outbreak of the COVID-19 crisis,

the Eurosystem also enhanced its provision of US dollar liquidity to banks and

created the Eurosystem repo facility for central banks (EUREP) to offer euro liquidity

to foreign central banks. The counterparty framework was also fine-tuned, while fully

preserving the Eurosystem’s first layer of risk protection (the second being collateral)

when conducting credit operations. Sections 4, 5 and 6 cover these developments.

Third, asset purchase programmes were conducted at an unprecedented scale to

preserve favourable financing conditions, in particular following the launch of the

pandemic emergency purchase programme (PEPP) in the early phase of the

pandemic. Overall, a maximum envelope of €1,850 billion in purchases was foreseen

under the PEPP, of which €1,581 billion had been used by the end of 2021. In

addition, the asset purchase programme (APP) was scaled up in March 2020 by a

total of €120 billion. In parallel, the Eurosystem continued lending part of its

securities under its securities lending programmes. Section 7 describes these

developments.

Finally, Section 8 considers the aggregate effect of the above instruments on the

Eurosystem balance sheet and related liquidity conditions, as well as the effects on

the distribution of excess liquidity and developments in autonomous factors,

including banknotes and government deposits. Overall, in this period, monetary

policy assets increased from €3.3 trillion at the end of 2019 to €6.8 trillion at the end

of 2021, thereby reaching a value equating to almost 60% of the euro area gross

domestic product (GDP).

1

Eser et al. (2012); Alvarez et al. (2016); Bock et al. (2018); Sylvestre and Coutinho (2020).

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 304 / September 2022

5

1 Introduction to the Eurosystem’s

monetary policy instruments in 2020

and 2021

The ECB’s response to the economic fallout from the outbreak of the COVID-

19 pandemic dominated its monetary policy action in the period under review,

namely from 1 January 2020 to 31 December 2021. In early 2020, the ECB

maintained a very accommodative monetary policy stance to support the medium-

term price stability objective. The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic and the

accompanying social restrictions to limit the spread of the virus changed the

economic and financial outlook drastically. The ECB faced the threat of a liquidity

and credit crunch, serious risks to the monetary policy transmission mechanism,

severe dislocations across market segments, and sharply decreasing market-based

inflation expectations, as evident, for instance, from market-based measures

(Chart 1). The ECB therefore substantially eased the monetary policy stance over

the course of 2020 to counter the negative impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the

euro area economy. Following the most acute phase of the pandemic, financial and

economic conditions recovered and the inflation outlook improved. Nonetheless, the

ECB’s policy response to the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic remained an

important determinant for the configuration of MPIs in place throughout the review

period and therefore constitutes a key element for this report.

Chart 1

Inflation expectations and government bond yields

(percentages per annum)

Source: Bloomberg.

Notes: Government bonds yields (10-year maturity) are weighted by GDP, based on the 11 largest euro area countries.

-1%

0%

1%

2%

3%

4%

01/20 04/20 07/20 10/20 01/21 04/21 07/21 10/21

Euro area weighted government bond yield

5-year to 5-year inflation swap

Euro area government bond yields (range)

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 304 / September 2022

6

1.1 Overview of monetary policy instruments

Over the review period, the Eurosystem introduced new measures and

recalibrated existing instruments in an unprecedented way to counter the

adverse effects of the pandemic. The Eurosystem balance sheet therefore

reached record levels. This report is structured around three main themes.

First, the ECB ensured an accommodative monetary policy stance by

maintaining the key ECB interest rates at record-low levels, reinforced by its

forward guidance on policy rates. As a result of the large liquidity injection, excess

liquidity in the euro area banking system continued maintaining the short-term

money market (which are used as reference rates) trading at or around the DFR. In

addition, the ECB actively used forward guidance in its communications to signal that

its policy rates would remain at their present level, or lower, until the inflation outlook

– including underlying inflation dynamics – were consistent with the Governing

Council’s inflation aim. It also stated that policy rates would not be raised before the

end of net purchases under the APP. After the conclusion of its strategy review, the

ECB further clarified the conditions under which it would consider raising its interest

rates. Finally, the ECB maintained its two-tier system (TTS) for reserve remuneration

to mitigate the side effects of the negative interest rate policy on the transmission of

monetary policy.

Chart 2

Euro area debt issuance and asset purchase programmes

(EUR billions)

Sources: ECB and ECB calculations

Notes: net debt issuances by issuer type, as indicated, and net volume purchased under the APP and PEPP programmes. Based on

monthly data. MFI stands for monetary financial institution.

Second, Eurosystem’s credit operations ensured that bank funding conditions

remained favourable and facilitated the banking sector in meeting the

increased loan demand during the pandemic. The conditions of the TLTRO III

programme were substantially eased by increasing banks’ borrowing allowance and

decreasing the applicable borrowing rate. These amendments contributed to record

(€2.2 trillion) participation in Eurosystem credit operations. Finally, an extension of

-100

0

100

200

300

400

01/19 04/19 07/19 10/19 01/20 04/20 07/20 10/20 01/21 04/21 07/21 10/21

MFIs

Government

Corporates

Net APP and PEPP

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 304 / September 2022

7

the collateral framework complemented the credit operations by increasing the

collateral availability to enable bank participation in these operations.

Third, asset purchase programmes contributed to delivering the appropriate

degree of monetary accommodation, stabilising financial markets and

preserving favourable financing conditions. The APP – which was already in

place before the pandemic – was upscaled, through duration extraction

2

and

signalling effects, to help provide the degree of policy accommodation needed to

ensure the convergence of inflation towards the aim. In addition, the PEPP was

launched in the early phase of the pandemic given that the financial markets had

frozen under the weight of rising uncertainty at that time. The PEPP aimed to support

the monetary policy stance and transmission by ensuring the Eurosystem’s a strong

market presence (Chart 2), as well as its flexibility over time, across asset classes

and among jurisdictions.

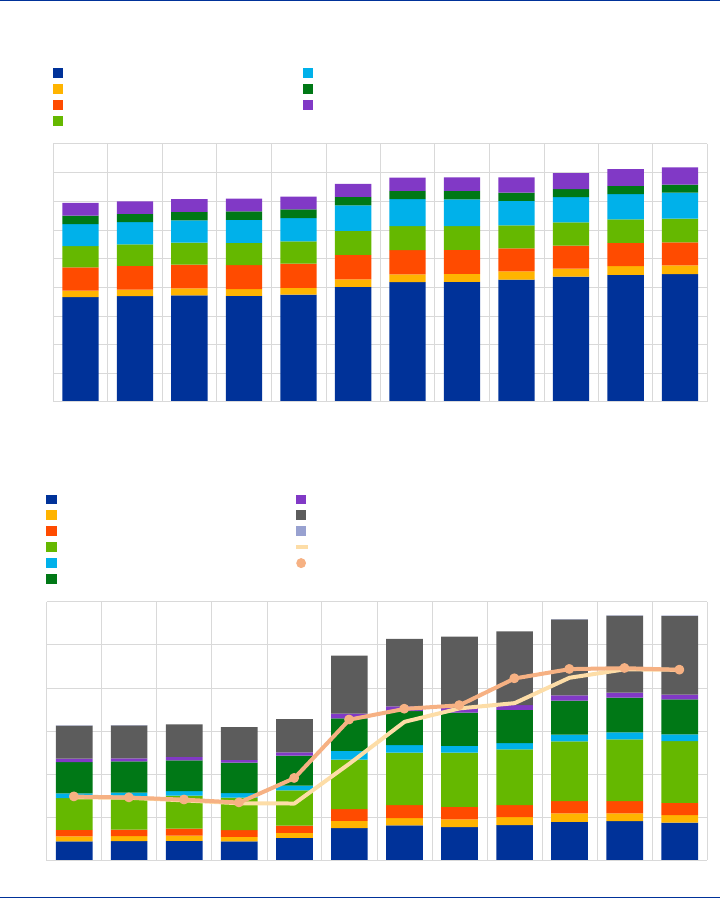

Chart 3

Monetary policy operations

(EUR billions)

Sources: ECB and ECB calculations

This report provides a thorough overview of the use of the Eurosystem

monetary policy implementation framework. It focuses on the 2020-2021 review

period, during which outstanding monetary policy operations (MPOs) reached

unprecedented levels (Chart 3). The structure of the review of MPIs will follow the

main three themes set out above, thereby deviating somewhat, in terms of outline,

from previous versions of the MPI report, while maintaining most of the sections

covered in previous reports

3

. Moreover, the report provides four boxes which offer

deeper insights into specific elements of relevance over the review period.

2

The duration extraction channel identifies a transmission channel for non-standard monetary policy

through which the central bank ‘extracts’ duration risk from the market through bond purchases while

letting its balance-sheet size grow.

3

Eser et al. (2012); Alvarez et al. (2016); Bock et al. (2018); Sylvestre and Coutinho (2020).

0

1,000

2,000

3,000

4,000

5,000

6,000

7,000

2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021

Global financial

crisis

Euro area sovereign

debt crisis

Coronavirus

pandemic crisis

Credit operations

Asset purchase programmes

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 304 / September 2022

8

2 Steering of short-term interest rates

In the high excess liquidity environment prevailing in the review period, money

market rates were steered towards the ECB’s DFR. The level of the DFR and

expectations about its future levels constitute the risk-free component of euro area

interest rates and yield curves and thus serve as the starting point for the monetary

policy transmission mechanism.

This section outlines the main developments in money markets and their interplay

with excess liquidity. Over the review period, the monetary policy implementation

framework to steer short-term interest rates remained unchanged; the developments

described below reflect the conduct of non-standard monetary policy measures

(such as asset purchase programmes) and external developments.

2.1 Main developments in excess liquidity and money

markets

During the review period, excess liquidity continued to increase and reached a

record level of €4.5 trillion in 2021. At the start of the review period in 2020, the

Eurosystem operated with a level of excess liquidity

4

of €1.7 trillion. As a result of

the monetary policy response to the outbreak of the pandemic, central bank reserves

increased strongly. Liquidity creation amounted to €3.7 trillion and resulted in €2.8

trillion of additional excess liquidity, with the difference (€0.9 trillion) being explained

by increased liquidity absorption through autonomous factors, such as banknotes

and non-monetary policy deposits (e.g. government deposits) (Chart 4a).

5

The

amount in central bank reserves provided the banking sector with ample scope to

meet the minimum reserve requirements (MRRs) and ensured that money market

rates remained closely linked to the DFR. Sections 3 and 8 provide more information

on developments with respect to MRRs and excess liquidity respectively.

Money market rates – and in particular the euro short-term rate (€STR) –

remained close to the DFR. The DFR was set at -0.50% in September 2019.

Money markets, and in particular the unsecured overnight rate (the €STR), traded

steadily below the DFR. Over the years 2020 and 2021, the €STR decreased on

average by 3 basis points to -0.57% (Chart 4b). While the €STR market is

characterised by transactions between banks and institutions that do not have direct

access to the deposit facility (DF) (non-banks, e.g. funds), an arbitrage mechanism

explains the differential between the DFR and the €STR.

6

Money market segments

4

Defined as the sum of holdings of central bank reserves in excess of reserve requirements and

holdings of equivalent central bank deposits (see Section 8).

5

See Section 8.3 for more detailed information.

6

Non-bank financial institutions (NBFIs) had been increasingly holding deposits often resulting from the

sale of securities to the Eurosystem. Since NBFIs do not fulfil the necessary Eurosystem eligibility

criteria and thus do not have access to the Eurosystem balance sheet, they resorted to banks for

liquidity storage by lending them liquidity, which banks in turn deposited with the Eurosystem by

charging a spread. As a result, benchmark rates, such as €STR, declined below the DFR.

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 304 / September 2022

9

with longer tenors or secured rates naturally reflect different risk premia and market

conditions. For example, the three-month euro interbank offered rate (EURIBOR)

peaked during the early phase of the pandemic, while at the same time some repo

rates (e.g. the German RepoFunds rate) fell to a lower level on 20 March 2020 (see

Box 1). However, both rates recovered after the decisions taken by the ECB

Governing Council on 24 March 2020.

Chart 4

Developments in excess liquidity and money market interest rates

a) Liquidity provision through MPOs and its

uses

b) The DFR and main money market rates vs

excess liquidity

(EUR trillions)

(left-hand scale: percentages per annum; right-hand scale: EUR

trillions)

Source: ECB, European Money Market Institute, Bloomberg

Note: the German RepoFunds rate reached -2.25% at the end of 2020 and -4.65% at the end of 2021 due to repo market dynamics.

Box 1

The interaction between developments in money markets and money market funds and

the ECB’s response during the COVID-19 crisis

This box focuses on the tensions in euro area money markets during the early stages of the

pandemic and the interplay with money market funds (MMFs). As a result of increased market

volatility and economic uncertainty, MMFs experienced significant outflows on the outbreak of

COVID-19 in March 2020 (Chart A). Prior to the COVID-19 stress, these funds held around 70% of

short-term (mostly private) debt issued in the euro area, and therefore play a vital role in money

markets. The stress placed on MMFs had implications for monetary policy transmission given its

impact on EURIBOR – an important reference rate for the euro area – and on banks’ liquidity

management.

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

01/20 07/20 01/21 07/21

Monetary policy operations

Minimum reserve requirements

Liquidity effect - autonomous factors

Excess liquidity

0

1

2

3

4

5

-1.0

-0.9

-0.8

-0.7

-0.6

-0.5

-0.4

-0.3

-0.2

-0.1

0.0

01/20 07/20 01/21 07/21

€STR

3-month Euribor

RepoFunds Rate (DE)

DFR

Excess liquidity (right-hand scale)

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 304 / September 2022

10

Chart A

Cumulative daily flows in the assets under management of European MMFs

(EUR billions)

Source: iMoneyNet.

Notes: iMoneyNet includes daily data on multiple characteristics of individual MMFs. While the database covers almost the entire US, for the euro area it

covers only Ireland and Luxembourg (and not France). Consequently, the results may differ slightly from those of other sources. Euro government funds are

excluded, as these are negligible. Black (grey) vertical bars show policy actions relating to asset purchases (refinancing operations). Remarkably, euro low

volatility funds experienced relatively large inflows at the beginning of the crisis in March 2020. This happened on the back of margin-related inflows owing to

the fact that the ECB surprised markets by keeping the DFR unchanged whereas the markets had fully priced in a rate cut. While this first led to MMF inflows,

resulting from gains on derivatives positions (through overnight index swaps (OISs)), margin calls also triggered a sharp reversal. Last observation: end of

January 2021.

MMFs came under pressure as economic stress and regulatory side effects increased outflows

The early phase of the pandemic was accompanied by an increased preference for liquidity on the

part of investors, banks and other parties. MMFs experienced substantial redemptions, driven by

the standstill in the global economy that significantly harmed traditional corporate cash flows.

Moreover, the uncertainty in financial markets led to growing liquidity needs (e.g. among pension

funds) to meet margin calls on derivatives exposures.

7

Finally, investors in MMFs redeemed cash

for precautionary reasons given that they were uncertain about the speed at which they would be

able to monetise assets. MMFs were challenged to meet these withdrawals given that securities

selling had to take place in illiquid markets or the funds had to draw down their weekly liquid asset

buffers.

While triggered by the COVID-19 shock, MMF outflows seem to have been amplified by regulatory

liquidity restrictions. Liquidity restrictions/redemption tools at fund level were introduced as part of

the MMF reforms introduced after the financial crisis to increase the soundness of that sector.

Funds of the type most common in Europe (low volatility net asset value funds) are required to keep

their weekly liquid assets above 30% of their net asset value (NAV) and the deviation of the mark-

to-market value NAV within 20 basis points.

8

In times of stress, MMFs have to sell assets to be able

to meet daily redemptions, while simultaneously complying with these liquidity restrictions. The

threat posed by the need to meet these restrictions may trigger procyclical investment behaviour,

7

See ECB (2020a).

8

Regulation (EU) 2017/1131 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 June 2017 on money

market funds (OJ L 169, 30.6.2017, p. 8). This Money Market Funds Regulation entered into force in

2019.

-5

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

01/20 03/20 05/20 07/20

Low volatility funds

Variable funds

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 304 / September 2022

11

leading to pre-emptive runs before the liquidity restrictions kick in. In March 2020, MMF outflows

were, indeed, more severe among funds with a lower percentage of liquid assets on their books.

9

Why was the stress among MMFs relevant for the ECB?

The MMF sector holds a substantial amount of short-term marketable debt (e.g. commercial paper

(CP)). While the majority of European banks have a large depositor base and, as a result, short-

term debt only makes up a small portion of their total funding mix,

10

CP plays an important role in

the liquidity management for banks given that it is often used to manage the liquidity coverage ratio

(LCR)

11

.

More importantly, stress in the CP market due to MMF liquidity strains had adverse consequences

on the transmission of monetary policy to the real economy. Following the benchmark reform of risk-

free rates in the euro area, rates on CP issued by banks are included in the EURIBOR calculation.

EURIBOR serves as an important benchmark for contracts worth some €180 trillion, including over

€1 trillion of retail mortgages.

12

Hence, the malfunctioning of CP markets that followed the

pronounced outflows from the MMF sector resulted in large spikes in bank CP rates, automatically

feeding into EURIBOR. As a result, EURIBOR rates rose to levels last seen in 2016, despite the

unprecedented monetary accommodation set by the Eurosystem (Chart B).

Chart B

EURIBOR rates

(percentages per annum)

Source: European Money Market Institute.

The monetary policy response

The Eurosystem took extensive measures to limit the negative effects of the COVID-19 crisis on the

economy and price stability. The impact on CP markets was alleviated by the purchase of non-

9

See ECB (2021a), Hudepohl et al. (2021), and ESMA (2021). The ESMA reported that no funds

breached the +/- 20 basis points collar in March, although a few funds were close to the threshold (e.g.

one fund had an 18 basis points deviation).

10

In fact, CP covers less than 3% of total funding needs and is thus only a minor source of bank funding.

Overarchingly, the share of deposit financing in total liabilities for the European banking sector in

general is more than ten times as large as the share of short-term marketable debt.

11

An important regulatory ratio which measures whether banks are capable of managing outflows over a

30-day period.

12

See “Euro money market reference rate”, European Money Market Institute website.

-0.7

-0.6

-0.5

-0.4

-0.3

-0.2

-0.1

0.0

01/16 01/17 01/18 01/19 01/20 01/21

3-month EURIBOR

6-month EURIBOR

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 304 / September 2022

12

financial CP with a minimum residual maturity of 28 days

13

and the broader acceptance of

uncovered bank bonds (the risk concentration limit having been increased from 2.5% to 10%).

Furthermore, the favourable conditions attaching to lending operations (additional long-term

refinancing operations (LTROs), pandemic emergency long-term financing operations (PELTRO)

and TLTROs) eased banks liquidity conditions and decreased their need to rely on market funding.

While these policy responses only supported MMFs indirectly, they helped to stabilise the money

markets effectively and money market rates such as EURIBOR started declining again towards

record-low levels. From a policy perspective and with a view to potential future such episodes, while

the extensive monetary policy measures taken by the Eurosystem helped to relieve stress in money

markets, adjusting regulation may prove particularly effective in enhancing the resilience of MMFs

in a more structural way.

14

13

Instead of the minimum residual maturity of six months that applies to other marketable debt

instruments with an initial maturity of at least 367 days covered by the corporate sector purchase

programme (CSPP).

14

ECB (2022); FSB (2021).

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 304 / September 2022

13

3 Minimum reserve requirements and the

two-tier system

MRRs have traditionally absorbed a relatively stable amount of liquidity given

an unchanged reserve ratio and only moderate growth in the relevant balance-

sheet items. The Eurosystem’s minimum reserve system traditionally served the

purpose of enlarging the structural liquidity deficit of the euro area banking system in

order to help steer short-term interest rates. Although this purpose has become less

relevant in recent years due to the large liquidity surplus, MRRs remain a standard

monetary policy implementation tool with euro area credit institutions being required

to hold a certain amount of funds as minimum reserves in their current accounts at

their respective national central banks (NCBs). In addition, the MRR has served as a

reference since October 2019 for the TTS, as explained below. The MRR is

calculated on the basis of the respective credit institution’s balance sheet prior to the

start of a maintenance period, and every credit institution must ensure that it holds

the required level of reserves, on average, over the relevant maintenance period.

The reserve requirement for each credit institution is calculated by multiplying

specific short-term liabilities by the reserve ratio, currently at 1% since January 2012.

The funds held to meet the MRR are remunerated at the main refinancing operations

(MRO) rate, that is to say, there are no costs for banks.

However, minimum reserves increased in absolute terms over the review

period due to the more pronounced increase in deposits on credit institution

balance sheets. MRRs gradually rose from €134.5 billion in January 2020 to €154.2

billion in December 2021 (Chart 5a), an increase of 14.7% compared with 8.4% in

the period from January 2018 to December 2019. This increase was driven by the

growth of credit institution liabilities subject to reserve requirements. While reserve

requirements grew in absolute terms, their share of total excess liquidity provided to

the banking system almost halved, from around 7.5% at the end of 2019 to 3.4% in

November 2021. This relative decline reflects the significant increase in excess

liquidity caused by the various pandemic-related measures (see Section 8), and was

most pronounced following the settlement of TLTRO III.4 on 24 June 2020.

The TTS addressed the side effects of the negative interest rate policy on the

transmission of monetary policy by exempting a portion of banks’ excess

reserves from negative remuneration. Frictions in the pass-through of negative

rates to banks’ funding costs when deposit rates are floored at zero (this is

particularly relevant for most of the retail deposits) may negatively affect bank profits

and thereby impair bank-based transmission of monetary policy. The TTS aims to

mitigate such impairments by exempting portions of credit institutions’ excess

reserves from negative remuneration at the DFR. The exempt tier was set in relation

to a credit institution’s MRR; the multiplier is the same for all credit institutions and

has remained unchanged at 6 during the review period.

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 304 / September 2022

14

Credit institutions made intensive use of the TTS and had nearly made full use

of it by the end of the review period. Most credit institutions in the euro area made

full use of their TTS allowance following its introduction, when 95.4% of the exempt

tier was used. In the review period, this increased to 99.4% as credit institutions

became more familiar with the system and optimised their reserve management. The

magnitude of use of the exempt tier mechanically followed the increase in MRR,

thereby rising from €804.8 billion in November 2019 to €925.4 billion in December

2021 (Chart 5b).

Chart 5

Developments in MRR and TTS

a) MRR vs excess liquidity

b) Fulfilment of TTS

(left-hand scale: EUR billions; right-hand scale: percentages per

annum)

(EUR billions)

Source: ECB and ECB calculations.

Note: based on maintenance period averages.

3.0%

4.0%

5.0%

6.0%

7.0%

8.0%

9.0%

120

125

130

135

140

145

150

155

01/18

07/18

01/19

07/19

01/20

07/20

01/21

07/21

Thousands

Reserve requirements

MRR in % of excess reserves (right-hand scale)

90%

91%

92%

93%

94%

95%

96%

97%

98%

99%

100%

0

500

1,000

1,500

2,000

2,500

3,000

3,500

4,000

4,500

5,000

MP 7 - 2019 MP 7 - 2020 MP 7 - 2021

Exempt excess liquidity (used allowance)

Non-exempt excess liquidity

% used allowance (right-hand scale)

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 304 / September 2022

15

4 Credit operations

Credit operations

15

are one of the cornerstones of the Eurosystem’s monetary

policy framework. The European banking sector plays an essential role in the

transmission of the ECB’s monetary policy. Through its credit operations, the ECB is

able to directly affect banks’ funding conditions, thereby preserving or stimulating

bank lending conditions. From the start of 2020, recourse to Eurosystem funding

significantly increased, moving from €627 billion to €2,207 billion, reversing the

downward trend seen in previous years (Chart 6).

This chapter distinguishes three main classes of credit operations:

• The TLTRO III programme provides banks with longer-term funding at attractive

conditions conditional on banks meeting a bank-specific pre-determined lending

benchmark. The operations are aimed at preserving favourable borrowing

conditions and are specifically designed to stimulate bank lending to the real

economy. During the review period, the ongoing series of TLTRO III operations

was adjusted in order to preserve bank lending amid the outbreak of the

COVID-19 pandemic.

• PELTROs, LTROs and MROs provide banks with funding at less attractive

terms compared with TLTRO III operations. While at the onset of the pandemic

the ECB’s response included the launch of PELTROs and additional LTROs at

relatively favourable pricing, three-month LTROs and MROs continued to be

offered under their customary conditions and played a role in providing liquidity

to smaller and/or specialised banks. In addition, the marginal lending facility

(MLF) remained available as a liquidity backstop.

• US dollar operations provide euro area banks with short-term US dollar

liquidity. With deteriorating liquidity in the US dollar funding market after the

outbreak of the pandemic, the conditions of the US dollar tenders offered by the

Eurosystem were temporarily eased.

All credit operations with banks are conducted on the basis of the Eurosystem

counterparty (see Section 5) and collateral frameworks (see Section 6). This chapter

also contains a subchapter elaborating on the foreign exchange arrangements

between central banks, which offer non-euro area banks the possibility of obtaining

euro outside the euro area.

15

Under Article 2(31) of Guideline (EU) 2015/510 of the European Central Bank of 19 December 2014 on

the implementation of the Eurosystem monetary policy framework (ECB/2014/60) (henceforth: the

General Documentation (GD)), Eurosystem credit operations means liquidity-providing reverse

transactions (i.e. liquidity-providing Eurosystem MPOs, excluding foreign exchange swaps for monetary

policy purposes and outright purchases) and intraday credit.

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 304 / September 2022

16

Chart 6

Participation in Eurosystem credit operations with eligible counterparties

(EUR billions)

Source: ECB.

4.1 TLTROs

The TLTRO III series was launched in September 2019. Through this targeted

programme the ECB provided banks with the opportunity to obtain three-year

funding up to a maximum amount. This borrowing allowance depended on the size

of the banks’ outstanding portfolio of loans to non-financial corporations (NFCs) and

households, excluding loans for house purchases. Banks received a discount on

their borrowing rate conditional on their lending performance.

With market stress rising following the outbreak of the pandemic, the ECB

enhanced the conditions of the TLTRO III programme to support bank lending.

This easing of the TLTRO III conditions was one of the key responses to the

pandemic. By April 2020, the ECB had introduced a special interest rate period,

running from June 2020 to June 2021, during which the interest rate on TLTRO III

operations was reduced to 50 basis points below the average interest rate prevailing

in the Eurosystem’s MRO rate over the same period. Moreover, for counterparties

whose eligible net lending reached the lending performance threshold, the interest

rate over the period from June 2020 to June 2021 would be 50 basis points below

the average DFR prevailing over the same period. Finally, the ECB raised the

maximum total amount that counterparties were allowed to borrow under TLTRO III.

In December 2020, in response to the economic fallout from the resurgence of the

pandemic in the euro area, the terms and conditions of the TLTRO III programme

were prolonged further (Table 1).

500

1,000

1,500

2,000

2,500

3,000

3,500

4,000

4,500

0

500

1,000

1,500

2,000

2,500

01/19 07/19 01/20 07/20 01/21 07/21

Thousands

MRO

3M LTRO

PELTRO

Additional LTRO

TLTRO II

TLTRO III

US dollar operations

Excess liquidity (right-hand scale)

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 304 / September 2022

17

Table 1

Main TLTRO III parameters before and after the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic

TLTRO III (pre-pandemic)

TLTRO III (until end 2021)

Operations

7 quarterly operations from September 2019 to

March 2021

10 quarterly operations from September 2019 to

December 2021

Maturity

3 years

Eligible loans

Loans to euro area NFCs and households, excluding loans for house purchases

Borrowing allowance

30% of the eligible loans

55% of the eligible loans

Interest rate

Between the MRO rate and DFR (average over

the life of the operations)

Between the MRO rate and DFR (average over the

life of the operations)

From June 2020 to June

2021 (special interest

rate period)

Between the MRO rate -

50 bps and DFR -50 bps

(average between June

2020 and June 2021)

From June 2021 to June

2022 (additional special

interest rate period)

Between MRO rate -50

bps and DFR -50 bps

(average between June

2020 and June 2021)

Benchmark net

lending (BNL)

Based on eligible net lending in the 12-month period to 31 March 2019

Positive eligible net lending: BNL = 0

Negative eligible net lending: BNL = eligible net lending in that period

Lending performance

thresholds

From 1 April 2019 to 31 March 2021: threshold of

at least 2.5% relative to benchmark outstanding

amount

16

From 1 April 2019 to 31

March 2021

Threshold of at least

1.15% relative to the

benchmark outstanding

amount

From 1 March 2020 to 31

March 2021 (special

reference period)

Threshold of at least 0%

relative to the BNL

From 1 October 2020 to

31 December 2021

(additional special

reference period)

Threshold of at least 0%

relative to the BNL

Voluntary repayment

options

Two years from settlement for each operation, at a

quarterly frequency

One year from settlement for each operation,

starting in September 2021, except for the last

three operations with the early repayment option

available from June 2022, at a quarterly frequency

Source: ECB.

Note: pre-pandemic parameters refer to the TLTRO III conditions from February 2020, and end-2021 parameters indicates the TLTRO

III conditions since March 2021, after the last enhancement of the TLTRO III parameters in December 2020.

Participation in TLTRO III reached record levels compared with the TLTRO I

and II series allotted between 2014 and 2017. The very favourable conditions of

the TLTRO III programme incentivised broad-based participation across euro area

banks. Participation per country was less concentrated compared with past series.

While under TLTRO II banks from Italy and Spain borrowed overall more than half of

the total outstanding amount, under TLTRO III their share declined to 37% over the

life of the operations. On the other hand, banks in France and Germany showed the

opposite behaviour, increasing their overall share from 28% under TLTRO II to 41%

under TLTRO III. Most of the participation took place following enhancement of the

borrowing conditions, namely under TLTRO III.4 in June 2020 and under TLTRO III.7

in March 2021 (Chart 7). The June 2020 TLTRO III operation, which marked the

beginning of the special interest rate period, saw the highest take-up, with 742 banks

participating for a total of €1,308 billion. In September 2021, Eurosystem outstanding

credit operations reached a new all-time high (€2,230 billion), doubling the peak

16

The benchmark outstanding amount is equal to the eligible stock of credit on 31 March 2019 plus the

BNL.

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 304 / September 2022

18

reached with the three-year LTROs programme in 2012. During the review period,

TLTROs represented, on average, more than 95% of the total outstanding

refinancing operations.

Banks have repaid €139 billion on the early repayment options dates for

TLTRO III in 2021. In the early repayment round in September 2021, 137

participants repaid a total of €79 billion, while in December 2021 a total of 72

participants repaid €60 billion. The net reduction in TLTRO usage of these banks

was, however, much lower (€35 billion) given that a large share of the funds was

repaid to be rolled over into the ninth or tenth TLTRO III series (with a longer

remaining maturity).

Chart 7

TLTRO III outstanding amounts and share of average TLTRO II and III outstanding

amounts

(EUR billions)

Source: ECB.

Note: The chart shows the outstanding amounts after the last TLTRO III operation. The share of average TLTRO II and TLTRO III

outstanding amounts considers the entire period under analysis.

Almost 92% of the participating banks met the special criteria (i.e. exceeded

the benchmark net lending in the special reference period) and benefited from

the most favourable interest rate applicable until June 2021. Around 3% of

banks did not exceed the special criteria but exceeded the initial criteria (i.e.

exceeded the net lending benchmark for the second reference period), and therefore

paid the DFR on their TLTRO III operations (Chart 8).

17

Banks that did not reach

their net lending benchmarks in any of the aforementioned reference periods – in

total, 5% of banks – obtained the less favourable interest rate, i.e. the MRO rate until

June 2020 and after June 2021, and the MRO rate minus 50 basis points during the

period between June 2020 and June 2021. Banks’ lending performance over the

additional special interest rate period was communicated in June 2022.

17

Note that 20% of these banks only partially exceeded the initial criteria i.e. the lending growth was

positive but lower than 1.15%. In these cases, the interest rate applied was between the average MRO

rate and the average DFR over the life of the operations.

0%

6%

12%

18%

24%

30%

36%

0

100

200

300

400

500

600

FR IT DE ES NL BE AT GR PT FI LU IE Others

TLTRO-III.1

TLTRO-III.2

TLTRO-III.3

TLTRO-III.4

TLTRO-III.5

TLTRO-III.6

TLTRO-III.7

TLTRO-III.8

TLTRO-III.9

TLTRO-III.10

Share of average TLTRO III outstanding amount (right-hand scale)

Share of average TLTRO II outstanding amount (right-hand scale)

0

500

1,000

1,500

2,000

2,500

EA

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 304 / September 2022

19

Chart 8

TLTRO III outstanding amounts by lending performance category

(EUR billions)

Source: ECB.

4.2 PELTROs, LTROs, MROs and the MLF

The ECB launched additional LTROs and PELTROs as temporary liquidity

backstops following the outbreak of the COVID-19 crisis. The additional LTROs

were designed to bridge liquidity needs until settlement of the fourth TLTRO III

operation in June 2020 – which was the first chance for banks to participate under

the eased TLTRO III conditions. The operations were offered at the DFR and,

compared with TLTRO III, without conditions, thereby allowing banks to swiftly

participate and build (precautionary) liquidity buffers. The volume of operations

peaked at around €390 billion in June 2020. The additional LTROs were

complemented by PELTROs, introduced in April 2020, to ensure sufficient liquidity

provision for banks that did not, or could not, participate in the TLTRO III series,

given their business models and the related availability and type of loan portfolios.

These operations were provided at an interest rate 25 basis points below the MRO

rate and had a maturity ranging from 8 to 16 months. Four additional PELTROs were

allotted in 2021. Outstanding PELTROs peaked at around €28 billion in July 2021.

Regular liquidity-providing refinancing operations continued to represent only

a small fraction of total Eurosystem lending. The regular refinancing operations,

i.e. the three-month LTROs and MROs, are currently only used by a small number of

banks. The operations have a maturity of three months and one week respectively,

and are both conducted under a full allotment procedure: MROs are conducted at an

interest rate at the MRO rate (which was maintained at 0% during the review period);

LTRO operations are conducted at the average MRO rate. The large amount of

excess liquidity in the system and the availability of more favourable TLTROs and

PELTROs reduced banks’ demand for MROs and three-month LTROs. The average

outstanding amounts in MROs and three-month LTROs during the period under

review were around €0.6 billion and €1.2 billion respectively. Average recourse to

these operations decreased by around €7 billion in 2020-21 compared with the

0

500

1,000

1,500

2,000

2,500

09/19 12/19 03/20 06/20 09/20 12/20 03/21 06/21 09/21 12/21

Thousands

Exceeded the special criteria

Exceeded the initial criteria only

Partially exceeded the initial criteria

Exceeded none of the criteria

Not defined yet

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 304 / September 2022

20

previous two years. From a country perspective, participation in regular MROs and

three-month LTROs was concentrated in Germany and Italy (around 75% of the

average volume over the review period).

18

Recourse to the MLF was occasional and due to unexpected payments or

technical failures. The MLF allows eligible counterparties to obtain overnight

liquidity at an interest rate above the MRO rate. The facility is designed to cover

specific liquidity shortfalls caused either by market developments or by technical

issues affecting the settlement of counterparties’ payments at a time of the day when

the counterparty is not able to find alternative funding on the market. Over the review

period the MLF rate remained constant at 0.25%, while recourse remained limited,

averaging just €12 million per day, which represents a significant reduction in

comparison with the daily average of €71 million in the previous review period. There

was, indeed, no participation in the MLF for almost two-thirds of the days in the

review period, while usage of the facility exceeded €100 million on only 12 days.

With more reserves available, counterparties increasingly used these to fund their

payments, thereby reducing their use of intraday credit.

19

In turn, lower intraday

credit meant that the likelihood of the automatic MLF being used at the end-of-day

decreased

20

. Occasional spikes above €100 million were mostly related to

unexpected payment outflows occurring late in the day and technical failures

impeding the correct settlement of upcoming inflows.

4.3 US dollar credit operations

US dollar tenders proved to be an important stabilising tool after the outbreak

of the pandemic, easing US dollar funding strains. Amid high volatility and risk

aversion, US dollar funding conditions for euro area banks deteriorated significantly

following the outbreak of the pandemic.

21

In response, the ECB and other major

central banks announced coordinated action to enhance the provision of US dollar

liquidity to banks outside the United States through the standing swap line (Section

4.4), and by lowering the rate to the OIS rate + 25 basis points

22

and reintroducing a

18

Smaller participation was recorded in Austria, France and Greece (around 6%, 4% and 2% respectively

of the average volume over the review period), while it was negligible or null in other jurisdictions.

19

Intraday credit is credit provided during the day free-of-charge and against eligible collateral (see point

(26) of Article 2 of Guideline of the European Central Bank of 5 December 2012 on a Trans-European

Automated Real-time Gross settlement Express Transfer system (TARGET2)(ECB/2012/27). If a

Eurosystem eligible counterparty does not repay the intraday credit by the end of the TARGET2

business day, its recourse is automatically converted into MLF and the MLF rate is applied.

20

See ECB (2021b).

21

For instance, the 3-month US funding premium in the EUR/USD foreign exchange swap market

peaked at roughly 140 basis points on 19 March 2020, surging from a daily average of 20 basis points

during January and February 2020 (Chart 9).

22

In October 2008, when the fixed-rate full allotment tender procedures were introduced, the pricing of

US dollar operations was changed from the rate charged in the Federal Reserve’s Term Auction Facility

(TAF) to a fixed rate of 100 basis points above the corresponding OIS rate. In November 2011, the

price was further reduced to OIS + 50 basis points, which remained in place until 15 March 2020, when

the Federal Reserve, the ECB, the Bank of Japan, the Bank of England, the Swiss National Bank and

the Bank of Canada introduced a new pricing.

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 304 / September 2022

21

weekly tender with a maturity of 84 days in addition to the existing 7-day operation.

23

Shortly thereafter, the frequency of the 7-day tender was increased from weekly to

daily.

24

These measures not only improved market sentiment by offering an effective

backstop, but also allowed banks to meet their funding needs immediately, easing

stress in US funding markets.

25

On 18 March 2020, the Eurosystem allotted USD 76

billion to 44 bidders under the 84-day operation and USD 36 billion to 22 bidders

under the 7-day operation. The total allotment of USD 112 billion on 18 March was

the highest in a single day since 2008. Usage of the facilities remained high during

the rest of March and April 2020, with the outstanding amount of US dollars

borrowed from the Eurosystem reaching an 11-year high of USD 145 billion in June

2020 (Chart 9).

Chart 9

USD funding conditions and usage of the Eurosystem USD facilities

(left-hand scale: EUR millions; right-hand scale: basis points)

Source: ECB and Bloomberg.

As US dollar funding conditions gradually normalised, recourse to US dollar

tenders dropped, in line with the backstop function of the facility. Starting in the

second half of April 2020, US funding conditions progressively improved, leading to a

decline in usage of the US dollar facility, which quickly lost its economic appeal.

Consequently, usage of US dollar swap lines dropped significantly over time. On 21

April 2020 the Eurosystem saw no bids for the first time since the onset of the

pandemic, with nil-bid operations becoming increasingly frequent thereafter. In June

2020 the average allotment per operation was USD 250 million, against over USD

600 million in May and roughly USD 10 billion between mid-March and mid-April.

The average take-up per operation remained low for the rest of 2020 and in 2021,

standing at USD 136 million between September 2020 and December 2021 as US

23

Enhancement of the swap line facilities was announced by the Federal Reserve, the ECB, the Bank of

Japan, the Bank of England, the Swiss National Bank and the Bank of Canada on 15 March 2020. For

more details, see the corresponding press release. The 84-day US dollar operation was reactivated for

the first time since 2014.

24

For more details, see the corresponding press release.

25

ECB (2020c).

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

160

0

20,000

40,000

60,000

80,000

100,000

120,000

140,000

160,000

01/20 04/20 07/20 10/20 01/21 04/21 07/21 10/21

Outstanding amount

US funding premium in the EURUSD foreign exchange swap market (right-hand scale)

Allotted amount in the 7-day operation

Allotted amount in the 84-day operation

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 304 / September 2022

22

dollar financing conditions broadly continued to be favourable.

26

Following the

improvement in US dollar funding conditions in offshore markets and the

corresponding drop in the use of the US dollar facility, the frequency of the 7-day

operation was gradually reduced from daily to three times a week from July 2020

and from three times a week to weekly from September 2020, while the weekly 84-

day operation was discontinued from July 2021.

4.4 The Eurosystem repo facility for central banks (EUREP)

and other repo agreements and foreign exchange swaps

with foreign central banks

Foreign-exchange (FX) swap and repo lines are arrangements between central

banks that are used to provide domestic banks with funding in foreign

currencies. These operations have a backstop function aimed at preventing or

easing cross-currency frictions. The swap line between the ECB and the Federal

Reserve is, for example, used by the ECB to lend to US dollars to euro area banks

with US dollar credit operations. Similarly, several FX swap and repo agreements

27

,

including the Eurosystem repo facility for central banks (EUREP), were established

to increase euro availability to central banks outside the euro area.

These two types of arrangement are designed to help domestic banks, through

the related credit operations offered by their respective central banks, to

satisfy their foreign currency needs during periods of market stress,

supporting the restoration of orderly market conditions. In normal times, there is

little systematic use of these arrangements given that market pricing would be more

favourable. However, if funding conditions become dysfunctional, as was the case at

the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, participation in the swap and repo lines

becomes more attractive and helps banks to satisfy their structural and immediate

funding needs, supporting the restoration of orderly market conditions. The mere

existence of precautionary liquidity arrangements has a calming effect on investors,

helping to maintain orderly market functioning.

The extension of the network of liquidity arrangements with other central

banks also ensured access to foreign liquidity during the pandemic period.

Following the outbreak of COVID-19, liquidity demand for precautionary and cash

management purposes surged globally, while heightened risk aversion hindered the

circulation of liquidity on a cross-border basis. Central banks around the world

reacted by reactivating and extending their network of swap and repo lines. In

particular, alongside the outstanding agreements, the Eurosystem swiftly reactivated

26

Occasional spikes in participation in the US dollar facility were observed at quarter-ends and especially

at year-ends, when, given tax considerations and regulatory requirements, banks are typically reluctant

to expand their balance sheet for intermediation activities, leading to tighter US dollar funding

conditions. However, during the review period, usage of the US dollar facility at quarter-ends remained

in line with the seasonal trend and, overall, was limited to a few counterparties.

27

From the Eurosystem perspective, swap line agreements allow the ECB to borrow foreign currency

from a foreign central bank against euro, with the promise to repay the borrowed currency plus a pre-

agreed interest rate on a specified future date. Under a repo line, a foreign central bank can borrow

euro from the ECB for a specific period at a pre-agreed interest rate in exchange for eligible assets

denominated in euro that are mobilised as collateral.

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 304 / September 2022

23

its swap line agreement with the Danish National Bank and set up temporary

precautionary swap line agreements with the Croatian National Bank and the

Bulgarian National Bank. In addition, the Eurosystem established temporary bilateral

repo lines with several other non-euro area central banks, namely the National Bank

of Romania, the Bank of Albania, the National Bank of North Macedonia, the

National Bank of Serbia, the Central Bank of the Republic of San Marino and the

Hungarian National Bank (Table 2). Finally, to complement the set of liquidity

agreements arranged with non-euro area counterparties, the ECB introduced the

Eurosystem repo facility for central banks (EUREP) in June 2020 as a precautionary

backstop to address pandemic-related euro liquidity needs outside the euro area.

Like other temporary pandemic-related measures, EUREP is a temporary facility and

will be available until January 2023.

28

Table 2

Overview of operational liquidity lines

Non-euro area counterpart

Type of arrangement

Reciprocal

Българска народна банка (Bulgarian National Bank)

Swap line

No

Danmarks Nationalbank

Swap line

No

Hrvatska narodna banka

Swap line

No

Sveriges Riksbank

Swap line

No

Bank of Canada

Swap line

Yes

People’s Bank of China

Swap line

Yes

Bank of Japan

Swap line

Yes

Swiss National Bank

Swap line

Yes

Bank of England

Swap line

Yes

Federal Reserve System

Swap line

Yes

Magyar Nemzeti Bank

Repo line

No

Banca Naţională a României

Repo line

No

Bank of Albania

Repo line

No

National Bank of North Macedonia

Repo line

No

Central Bank of the Republic of San Marino

Repo line

No

National Bank of Serbia

Repo line

No

Source: ECB.

Note: The table does not include repo lines established with non-euro area central banks under EUREP, for which the ECB does not

disclose its counterparties.

28

In view of the highly uncertain environment caused by the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the risk of

regional spillovers that could adversely affect euro area financial markets, on 10 March 2022 the

Governing Council decided to extend the EUREP facility until 15 January 2023.

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 304 / September 2022

24

5 Counterparty framework

The Eurosystem counterparty framework sets the eligibility criteria that euro area

credit institutions must comply with in order to be granted access to MPOs.

29

The

framework is designed to ensure that a broad range of counterparties may

participate in Eurosystem MPOs, while protecting the Eurosystem from the risk of a

counterparty defaulting. Over the review period the Eurosystem counterparty

framework was amended to: 1) introduce a more direct mapping of failures to meet

minimum regulatory requirements to restrictions in counterparty access to

Eurosystem MPOs, i.e. some automaticity in the application of discretionary

measures, and 2) be aligned with the treatment of the leverage ratio requirement

under the Capital Requirements Regulation (CRR)

30

, which is relevant for assessing

financial soundness as required under the GD.

5.1 Eligibility criteria and discretionary measures

Eligibility criteria for participation in Eurosystem MPOs remained largely

unaltered in the review period. To qualify as an eligible counterparty, a credit

institution needs to

31

:

1. be subject to Eurosystem’s minimum reserve requirements;

2. be supervised by competent authorities;

3. be financially sound; and

4. fulfil the operational requirements of the local NCB for participation in MPOs.

32

The first requirement grants euro area credit institutions access to MPOs. The

second and third requirements provide the Eurosystem with a first layer of risk

protection. Financial soundness requires assessment by the Eurosystem, which may

take into account prudential information on capital, leverage and liquidity ratios.

33

In 2021 the Eurosystem enhanced the efficiency and consistency of

application of the counterparty framework. The Eurosystem may suspend, limit,

or even exclude, an individual counterparty’s access to MPOs if that counterparty is

29

Monetary policy eligible counterparties (MPECs) are defined as counterparties having access to either

liquidity-providing operations and/or liquidity-absorbing operations and/or to standing facilities.

Counterparties for outright purchases are not MPECs. MPECs are a subset of euro area credit

institutions subject to minimum reserve requirements, the number of such institutions having decreased

from 4,462 to 4,308 during the review period.

30

Regulation (EU) No 575/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 June 2013 on

prudential requirements for credit institutions and investment firms and amending Regulation (EU)

No 648/2012 (OJ L 176, 27.6.2013, p. 1).

31

Article 55 of the General Documentation.

32

Access to Eurosystem MPOs is granted by the relevant NCB to counterparties that fulfil the eligibility

criteria set in line with the decentralised monetary policy implementation in the euro area.

33

Article 55a of the General Documentation.

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 304 / September 2022

25

in breach of the eligibility criteria.

34

Until 2021 the Eurosystem determined which of

the three above-mentioned actions was warranted by assessing the specific case

concerned.

35

On 1 January 2021 the Eurosystem adopted a more rule-based

approach to this process aimed at enhancing its internal efficiency and ensuring

consistent application of the framework across counterparties. Specifically, when

own funds requirements are breached, the Eurosystem limits the counterparty’s

access to MPOs, on the grounds of prudence, to the level prevailing when that non-

compliance is notified to the Eurosystem. If compliance with own funds requirements

has not been restored at the latest within 20 weeks from the identification of the non-

compliance, the counterparty’s access to MPO is suspended. Similarly, if the

required information related to own funds requirements is incomplete or not

available, the Eurosystem may limit a counterparty’s access to MPOs 14 weeks after

the reference date, and may suspend the counterparty after 20 weeks.

36

Over the

review period, 17 banks were the subject of Eurosystem discretionary measures,

namely three limitations and 14 suspensions.

37

The counterparty framework rules relevant for assessing financial soundness

were amended in line with the relevant EU prudential regulation. To ensure

consistency with the regulatory framework, the Eurosystem adopted the relevant

definitions under the CRR. Consequently, on 28 June 2021, when the regulatory

requirement making the leverage ratio binding came into force

38

, the Eurosystem

aligned treatment of the leverage ratio requirement in the Eurosystem counterparty

framework with that of the existing Pillar 1 own funds requirements.

39

Since then,

fulfilment of the leverage ratio requirement has been monitored on a regular basis as

is the case with capital ratios. Accordingly, breaches and incomplete reporting of the

leverage ratio trigger the discretionary measures explained above.

5.2 Counterparties’ developments

Over the review period the number of monetary policy eligible counterparties

(MPECs) continued to decrease, mainly on the back of consolidation of the EU

banking sector. By the end of 2021, 1,869 credit institutions classified as MPECs

(out of the 4,308 credit institutions in the euro area at the end of the reference

period). The change in the number of MPECs was mainly driven by corporate events

that to some extent reshaped the EU banking system, with a net overall decrease in

MPECs of 148 over the review period (Chart 10a). The net decrease was mainly due

34

Article 158 of the General Documentation.

35

If a counterparty is suspended or excluded from access to MPOs, it must repay the outstanding credit

operations (including accrued interest) in full, by a date decided by the Eurosystem. Under a limitation,

the counterparty does not have to repay its outstanding credit operations (but may not increase its

borrowed amount). The Eurosystem may revoke a limitation or suspension, but exclusions are

expected to be permanent.

36

Where this occurs, just as before 2021, the Eurosystem may limit access to MPOs once the reporting

breach is detected and until either (1) the counterparty reports the relevant information, or (2) the

counterparty is suspended.

37

Of these banks, 5 counterparties re-gained access to MPOs during the review period.

38

The binding leverage ratio requirement is usually 3%, unless adjusted in accordance with Article

429a(7) of Regulation (EU) No 876/2019 (CRR2).

39

Common Equity Tier 1 capital ratio (4.5%), Tier 1 capital ratio (6%), total capital ratio (8%).

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 304 / September 2022

26

to the voluntary withdrawal by the counterparties concerned from their status as

Eurosystem eligible counterparties, followed, in order of relevance, by consolidation

activities, cessation of activity due to the withdrawal of banking licences, liquidations

and closures (typically of foreign branches). At the same time, some new banks were

established across the euro area, thereby partially offsetting the decrease.

The majority of new MPECs participated in at least one credit operation, while

access requests for intraday credit and the MLF were mainly precautionary.

When applying for access to Eurosystem credit operations, credit institutions may

also request access to Eurosystem MPOs, including the standing facilities and

intraday credit, depending on their business needs. In the period under review more

than 70% of new eligible counterparties, amounting in total to 63 new MPECs,

participated in one or more credit operations soon after having become eligible, while

the remainder mainly requested access on precautionary grounds. Just 40% had

recourse to intraday credit or overnight credit through the MLF (Chart 10b). This

suggests that the intention to participate in longer tenor operations, such as TLTRO

III operations, may have been the main driver for new access requests over the

review period.

Chart 10

Developments in MPECs

a) Drivers of the net decrease in the number

of MPECs

b) Use of Eurosystem facilities by newly

eligible MPECs

(units)

(percentages per annum)

Source: ECB

Notes: the left panel: ‘New MPEC accesses’ identify either new banks or banks that have requested access as an eligible counterparty

to any Eurosystem facility in the review period. ‘Withdrawal by counterparties’ identifies banks that voluntarily withdrew from

Eurosystem facilities. ‘Consolidation’ identifies the net figure for merger and acquisition activity in terms of legal entities having access

to Eurosystem facilities. ‘Cessation of bank activity’ identifies banking licence withdrawals, and bank closures or liquidation. The right

panel: ‘active MPECs’ identifies newly eligible MPECs that made use of the facility at least once in the period under review; ‘inactive

MPECs’ identifies newly eligible MPECs that made no use of the facility in the period under review. ‘Longer tenors’ refers to MROs,

LTROs and TLTROs. ‘Intraday/overnight’ identifies use of intraday credit and/or marginal lending facilities by the end of the day.

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

Longer tenors Intraday/overnight

Number of active MPECs

Number of inactive MPECs

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 304 / September 2022

27

6 Collateral framework

The Eurosystem collateral framework regulates the collateralisation of Eurosystem

credit operations and provides a second layer of protection against counterparty

default

40

. In the period under review, the temporary collateral easing measures in

response to the pandemic were the major innovation. In addition, the Eurosystem

extended collateral eligibility to sustainability-linked bonds, made the necessary

adaptations following Brexit and introduced adjustments to increase transparency

and reduce the overall complexity of the Eurosystem collateral framework.

41

6.1 Changes to the collateral framework

Collateral rules were temporarily broadened in response to the emergency

created by the COVID-19 pandemic. The Eurosystem introduced temporary

collateral easing measures in April 2020

42

, these being further extended in

December 2020 until June 2022. The measures included an increase in the types of

credit claims that were eligible as collateral (including loans benefiting from the

guarantee schemes adopted in euro area Member States in response to the

pandemic), the maintenance of eligibility – under some conditions – for assets that

fulfilled credit quality requirements at the onset of the pandemic, a reduction in

collateral valuation haircuts by a fixed factor of 20%, and a waiver of the minimum

rating requirement for marketable debt securities issued by the Hellenic Republic.

These measures were introduced to facilitate the availability of eligible collateral for

Eurosystem counterparties to be able to participate in liquidity-providing operations,

such as the TLTRO III series, and to facilitate an increase in bank funding against

loans to corporates and households. ECB estimates suggest that collateral easing

measures have contributed to approx. 23% of the total increase in the value after

haircuts of mobilised collateral since the start of the pandemic and account for 10%

of the currently mobilised collateral (Chart 11)

43

. The increase in collateral value due

to these collateral easing measures was predominantly driven by the expansion of

additional credit claim frameworks (€162 billion) and by the temporary haircut

reduction (€113 billion). In March 2022 the ECB announced the gradual phase-out of

the pandemic collateral easing measures in three stages between July 2022 and

March 2024

44

.

40

For further information on how the collateral framework has been developed over the years, see

Bindseil et al. (2017).

41

See Guideline (EU) 2020/1690 of the European Central Bank of 25 September 2020 amending

Guideline (EU) 2015/510 on the implementation of the Eurosystem monetary policy framework

(ECB/2020/45).

42

For further details, see the ECB press releases of 7 April 2020 and 22 April 2020.

43

The analysis covers the period between 27 February 2020 and 30 September 2021.

44

For further details, see the ECB press release of 24 March 2022.

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 304 / September 2022

28

Chart 11

Impact of temporary collateral easing measures on mobilised collateral value

(EUR billions)

Source: ECB, Eurosystem and ECB calculations.

Notes: The bar chart shows the mobilisation of Eurosystem-eligible collateral by asset category, and the values are after valuation and

haircuts. The first observation shows the composition of collateral before the outbreak of the pandemic, on 27 February 2020. The

cross-shaded areas in the bars on the right-hand side show the total collateral value due to the collateral easing measures for the

respective asset category on 30 September 2021.

The expansion of the additional credit claim (ACC) frameworks significantly

increased the availability of non-marketable assets as collateral. The revised

framework has allowed NCBs to additionally accept loans to small and medium-sized

enterprises or self-employed individuals as collateral provided that they are covered

by COVID-19-related government and other public sector guarantee schemes.

45

In

addition, several other measures were implemented to broaden the availability and

ease the mobilisation of ACCs.

46

Box 2 reviews the principles behind acceptance of

government/public sector guaranteed loans into the ACC framework.

The eligibility ‘freeze’ shielded collateral from potential downgrades that could

have reduced the availability of marketable assets. At the outbreak of the

pandemic, a sudden shortage in collateral availability due to a wave of potential

downgrades could have depressed banks’ lending activity and exacerbated the crisis

in a procyclical manner. To pre-empt this, on 7 April 2020 the Eurosystem

temporarily froze the eligibility of marketable assets that fulfilled minimum credit

quality requirements, provided that the asset ratings remained above credit quality

step 5

47

and all other eligibility requirements were fulfilled. Assets that fell below the

minimum credit quality requirements were subject to haircuts based on their actual

45

The ACC framework was introduced in 2012 and regulates credit claims that do not fulfil all the

eligibility criteria applicable under the general collateral framework. Until the 2020 extension, ACCs

included pools of loans to households as well as pools of similar kinds of loans, consisting of, for

instance, corporate loans, small and medium-sized enterprise (SME) loans, consumer loans or

mortgages (consumer loans and mortgages are loans to households; individual ACCs include only

loans to corporates/SMEs). ACCs could also be of lower credit quality than the generally accepted

credit claims or be denominated in currencies other than the euro.

46

The measures included: 1) expansion of the scope of acceptable credit assessment systems. For

example, several NCBs with an in-house credit assessment system (ICAS) decided to complement

their existing ICASs with more resource-efficient statistical ICAS (see Box 1 in Auria et al. (2021)) and

other NCB-specific credit assessment approaches, or by easing acceptance of banks’ own credit

assessments from internal rating-based systems that were approved by supervisors; 2) a reduction in